The Newark Academy of Delaware in Colonial Days1 by George H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the Presbyterian Historical Society

JOURNAL OF tHE Presbyterian Historical Society. Vol. I., No. 4. Philadelphia, Pa. June A. D., 1902. THE EARLY EDITIONS OF WATTS'S HYMNS. By LOUIS F. BENSON, D. D. Not many books were reprinted more frequently during the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century than the Hymns and Spiritual Songs of Isaac Watts. Few books became more familiar, and certainly but few played a greater part in the history of our American Presbyterianism, both in its worship and in its strifes. But with all this familiarity and multiplica tion of editions, the early history, textual and bibliographical, of the hymns has remained practically unknown. This is ac counted for by the fact that by the time interest in such studies began to be awakened, the early editions of the book itself had disappeared from sight. As long ago as 1854, Peter Cunningham, when editing the Life of Watts in Johnson's Lives of the Poets, stated that "a first edition of his Hymns, 1707, is rarer than a first edition of the Pilgrim's Progress, of which it is said only one copy is known." The second edition is not less rare. The Rev. James Mearns, assistant editor of Julian's Dictionary of Hymnology, stated (The Guardian, London, January 29, 1902) that he had never seen or heard of a copy. Even now the British Museum possesses nothing earlier than the fifth edition of 1716. It has (265 ) THE LOG COLLEGE OF NESHAM1NY AND PRINCETON UNIVERSITY. By ELIJAH R. CRAVEN, D. D., LL, D. After long and careful examination of the subject, I am con vinced that while there is no apparent evidence of a legal con nection between the two institutions, the proof of their connec tion as schools of learning — the latter taking the place of the former — is complete. -

Philadelphia, the Indispensable City of the American Founding the FPRI Ginsburg—Satell Lecture 2020 Colonial Philadelphia

Philadelphia, the Indispensable City of the American Founding The FPRI Ginsburg—Satell Lecture 2020 Colonial Philadelphia Though its population was only 35,000 to 40,000 around 1776 Philadelphia was the largest city in North America and the second-largest English- speaking city in the world! Its harbor and central location made it a natural crossroads for the 13 British colonies. Its population was also unusually diverse, since the original Quaker colonists had become a dwindling minority among other English, Scottish, and Welsh inhabitants, a large admixture of Germans, plus French Huguenots, Dutchmen, and Sephardic Jews. But Beware of Prolepsis! Despite the city’s key position its centrality to the American Revolution was by no means inevitable. For that matter, American independence itself was by no means inevitable. For instance, William Penn (above) and Benjamin Franklin (below) were both ardent imperial patriots. We learned of Franklin’s loyalty to King George III last time…. Benjamin Franklin … … and the Crisis of the British Empire The FPRI Ginsburg-Satell Lecture 2019 The First Continental Congress met at Carpenters Hall in Philadelphia where representatives of 12 of the colonies met to protest Parliament’s Coercive Acts, deemed “Intolerable” by Americans. But Congress (narrowly) rejected the Galloway Plan under which Americans would form their own legislature and tax themselves on behalf of the British crown. Hence, “no taxation without representation” wasn’t really the issue. WHAT IF… The Redcoats had won the Battle of Bunker Hill (left)? The Continental Army had not escaped capture on Long Island (right)? Washington had been shot at the Battle of Brandywine (left)? Or dared not undertake the risky Yorktown campaign (right)? Why did King Charles II grant William Penn a charter for a New World colony nearly as large as England itself? Nobody knows, but his intention was to found a Quaker colony dedicated to peace, religious toleration, and prosperity. -

Tennessee Counties Named for Patriots & Founding Fathers

Tennessee Counties named for Patriots & Founding Fathers Photo County amed for Anderson County Joseph Anderson (1757-1837), U.S. Senator from TN, and first Comptroller of the U.S. Treasury. During the Revolutionary War, he was an officer in the New Jersey Line of the Continental Army. Bedford County Revolutionary War Officer Thomas Bedford Bledsoe County Anthony Bledsoe (ca 1795-1793), Revolutionary War Soldier, Surveyer, and early settler of Sumner County. Blount County William Blount (1749-1800) was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of North Carolina, the first and only Governor of the Southwest Territory, and was appointed as the Regimental Paymaster of the 3rd NC. Regiment during the Revolutionary War. Davidson County William Lee Davidson (1746-1781) a Brigadier General who died in the Revolutionary War Battle of Cowan’s Ford. DeKalb County Johann de Kalb (1721-1780) A German-born baron who assisted the Continentals during the Revolutionary War Fayette County Marquis de La Fayette (1757-1834) a French aristocrat and military officer who was a General in the Revolutionary War Franklin County Founding Father Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) Greene County Nathaniel Greene (1742-1786) Major General in the Continental Army During the Revolutionary War. Hamilton County Founding Father Alexander Hamilton (ca.1755- 1804) Hancock County John Hancock (1737-1794) President of the Continental Congress Hawkins County Benjamin Hawkins (1754-1816) was commissioned as a Colonel in the Continental Army where he served under George Washington for several years as his main French interpreter. Henry County Revolutionary-era Patriot Patrick Henry (1736- 1799) Jackson County Revolutionary War Veteran and President Andrew Jackson (1767-1845). -

History of Neshaminy Presbyterian Church of Warwick, Hartsville

HISTORY shaming ;jr^slrgtiriHn :yjturrh v7".A.:E^-^Arioic, HARTSVILLE, BUCKS COUNTY, PA. 17^6-187^. BY • REV. DfX. TURNER. PUBLISHED BY REQUEST OF THE SESSION. PHILADELPHIA : CULBERTSON & BACHE, PRINTERS, 727 JaYNE StREET. 1876. o o CO TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE. ' Correspondence, • ' ^}. ^i" Succession of Pastors, .... xv • • • • Preface, . • f CHAPTER I. EARLY SETTLEMENT. Jamison's Location of Neshaminy Church.—Forks of Neshaminy.— Corner.—Founding of the Church.—Rev. P. Van Vleck.—Deeds and yiven by WiLiam Penn.—Holland Churches at Feasterville Richborough.—Bensalem.—Few Presbyterian Churches.—The Scotch Irish. ....•• CHAPTER II. REV. WILLIAM TENNENT. Mr. Tennent's birth and education.—His ordination in the Episco- Presbyterian pal Church.—Marriage.—He unites with the Church.—Reasons for his change of ecclesiastical relation.— Takes Residence at Bensalem, Northampton and Warminster.— " Rev. charge of the Church at Neshaminy.—The Old Side."— Grave George Whitefield visits Neshaminy.—Preaches in the § Yard.—" Log College." CHAPTER III. SONS OF REV. WILLIAM TENNENT. N. J., and Rev. Gilbert Tennent.—His pastorate at Kew^ Brunswick, character. Rev. in Philadelphia.—His death and burial.—His William Tennent, Jr.—Education.—Residence in New Bruns- wick.—The trance.—Apparent death and preparation for burial. —His recovery.—Account of his view of Heaven.—Settlement Settlement at Freehold, N. J.—Death. Rev. John Tennent.— early age. Rev. at Freehold.—Usefulness.—Death at an Charles Tennent—Ordination at Whiteclay Creek, Delaware.— with the Residence at Buckingham, Maryland.—His connection "New Side."—Mrs. Douglass. -Rev. William M. Tennent, 19 D. D. — IV CONTENTS. CHAPTER IV. ALUMNI OF LOG COLLEGE. Rev. Samuel Blair.—Settlement at Shrewsbury, N. -

The Signers of the U.S. Constitution

CONSTITUTIONFACTS.COM The U.S Constitution & Amendments: About the Signers (Continued) The Signers of the U.S. Constitution On September 17, 1787, the Constitutional Convention came to a close in the Assembly Room of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There were seventy individuals chosen to attend the meetings with the initial purpose of amending the Articles of Confederation. Rhode Island opted to not send any delegates. Fifty-five men attended most of the meetings, there were never more than forty-six present at any one time, and ultimately only thirty-nine delegates actually signed the Constitution. (William Jackson, who was the secretary of the convention, but not a delegate, also signed the Constitution. John Delaware was absent but had another delegate sign for him.) While offering incredible contributions, George Mason of Virginia, Edmund Randolph of Virginia, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts refused to sign the final document because of basic philosophical differences. Mainly, they were fearful of an all-powerful government and wanted a bill of rights added to protect the rights of the people. The following is a list of those individuals who signed the Constitution along with a brief bit of information concerning what happened to each person after 1787. Many of those who signed the Constitution went on to serve more years in public service under the new form of government. The states are listed in alphabetical order followed by each state’s signers. Connecticut William S. Johnson (1727-1819)—He became the president of Columbia College (formerly known as King’s College), and was then appointed as a United States Senator in 1789. -

Presbyterians and Revival Keith Edward Beebe Whitworth University, [email protected]

Whitworth Digital Commons Whitworth University Theology Faculty Scholarship Theology 5-2000 Touched by the Fire: Presbyterians and Revival Keith Edward Beebe Whitworth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/theologyfaculty Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Beebe, Keith Edward. "Touched by the Fire: Presbyterians and Revival." Theology Matters 6.2 (2000): 1-8. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theology at Whitworth University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Whitworth University. TTheology MMattersatters A Publication of Presbyterians for Faith, Family and Ministry Vol 6 No 2 • Mar/Apr 2000 Touched By The Fire: Presbyterians and Revival By Keith Edward Beebe St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland, Undoubtedly, the preceding account might come as a Tuesday, March 30, 1596 surprise to many Presbyterians, as would the assertion that As the Holy Spirit pierces their hearts with razor- such experiences were a familiar part of the spiritual sharp conviction, John Davidson concludes his terrain of our early Scottish ancestors. What may now message, steps down from the pulpit, and quietly seem foreign to the sensibilities and experience of present- returns to his seat. With downcast eyes and heaviness day Presbyterians was an integral part of our early of heart, the assembled leaders silently reflect upon spiritual heritage. Our Presbyterian ancestors were no their lives and ministry. The words they have just strangers to spiritual revival, nor to the unusual heard are true and the magnitude of their sin is phenomena that often accompanied it. -

A Timeline of Bucks County History 1600S-1900S-Rev2

A TIMELINE OF BUCKS COUNTY HISTORY— 1600s-1900s 1600’s Before c. A.D. 1609 - The native peoples of the Delaware Valley, those who greet the first European explorers, traders and settlers, are the Lenni Lenape Indians. Lenni Lenape is a bit of a redundancy that can be translated as the “original people” or “common people.” Right: A prehistoric pot (reconstructed from fragments), dating 500 B.C.E. to A.D. 1100, found in a rockshelter in northern Bucks County. This clay vessel, likely intended for storage, was made by ancestors of the Lenape in the Delaware Valley. Mercer Museum Collection. 1609 - First Europeans encountered by the Lenape are the Dutch: Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing under the Dutch flag, sailed up Delaware Bay. 1633 - English Captain Thomas Yong tries to probe the wilderness that will become known as Bucks County but only gets as far as the Falls of the Delaware River at today’s Morrisville. 1640 - Portions of lower Bucks County fall within the bounds of land purchased from the Lenape by the Swedes, and a handful of Swedish settlers begin building log houses and other structures in the region. 1664 - An island in the Delaware River, called Sankhickans, is the first documented grant of land to a European - Samuel Edsall - within the boundaries of Bucks County. 1668 - The first grant of land in Bucks County is made resulting in an actual settlement - to Peter Alrichs for two islands in the Delaware River. 1679 - Crewcorne, the first Bucks County village, is founded on the present day site of Morrisville. -

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb. -

H. Doc. 108-222

34 Biographical Directory DELEGATES IN THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS CONNECTICUT Dates of Attendance Andrew Adams............................ 1778 Benjamin Huntington................ 1780, Joseph Spencer ........................... 1779 Joseph P. Cooke ............... 1784–1785, 1782–1783, 1788 Jonathan Sturges........................ 1786 1787–1788 Samuel Huntington ................... 1776, James Wadsworth....................... 1784 Silas Deane ....................... 1774–1776 1778–1781, 1783 Jeremiah Wadsworth.................. 1788 Eliphalet Dyer.................. 1774–1779, William S. Johnson........... 1785–1787 William Williams .............. 1776–1777 1782–1783 Richard Law............ 1777, 1781–1782 Oliver Wolcott .................. 1776–1778, Pierpont Edwards ....................... 1788 Stephen M. Mitchell ......... 1785–1788 1780–1783 Oliver Ellsworth................ 1778–1783 Jesse Root.......................... 1778–1782 Titus Hosmer .............................. 1778 Roger Sherman ....... 1774–1781, 1784 Delegates Who Did Not Attend and Dates of Election John Canfield .............................. 1786 William Hillhouse............. 1783, 1785 Joseph Trumbull......................... 1774 Charles C. Chandler................... 1784 William Pitkin............................. 1784 Erastus Wolcott ...... 1774, 1787, 1788 John Chester..................... 1787, 1788 Jedediah Strong...... 1782, 1783, 1784 James Hillhouse ............... 1786, 1788 John Treadwell ....... 1784, 1785, 1787 DELAWARE Dates of Attendance Gunning Bedford, -

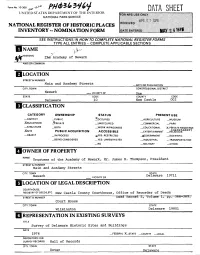

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 ^O' 1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC .The"' Academy of Newark AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Newark _ VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _3>RIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE JiSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _ REGifc^S 6 —OBJECT _ INPROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED -^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trustees of the Academy of Newark, Mr. James H. Thompson, President STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets CITY, TOWN Delaware 19711 Newark VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle County Courthouse, Office of Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Deed Record Z , Volume 366 369, Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 19801 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1974 —FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE 1LGOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Academy Square/ at the southeast corner of Main and Academy Streets, is a park, on the south side of which is the Academy of Newark building. -

A Political Biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1979 A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776 John Thomas anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation anderson, John Thomas, "A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776" (1979). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625075. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tdv7-hy77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF JOHN WITHERSPOON * L FROM 1723 TO 1776 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts *y John Thomas Anderson APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, September 1979 John Michael McGiffert (J ^ j i/u?wi yybirvjf \}vr James J. Thompson, Jr. To my parents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION....................... ill TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................... v ABSTRACT........... vi INTRODUCTION................. 2 CHAPTER I. "OUR NOBLE, VENERABLE, REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": JOHN WITHERSPOON IN SCOTLAND, 1723-1768 . ............ 5 CHAPTER II. "AN EQUAL REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": WITHERSPOON IN NEW JERSEY, 1768-1776 37 NOTES . -

New Jersey Society About the Middle of the Eighteenth Century

I 4 f ^'^ '^^ " - -'^.^ . t UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY Nt Class Book Volume ^'4 MrlO-20M :,;>#:^; . ^ l|^ ^ ,f._ 4^ 4^ - . ,/., 4 The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, ond underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSI TY or- I Ll l NO IS- MiHABY l l gRAtjA-CHAMPAIGN r «tlURr^ (U IHESElS COLLECTKDN BUiLOiNG USE OfJlY u4 4- L161—O-1096 t- -f- * 4 •^ '•"--4- ^4- -I- 4 - ^ -I f , f- ^ f 4 -f' if i'- -f- ^- Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/newjerseysocietyOOmoor NEW JERSEY SOCIETY ABOUT THE MIDDLE OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY BY ELLSWORTH MOORE THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN HISTORY IN THE COLLEGE OF LITERATURE AND ARTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESENTED JUNE, 1910 ... Nil UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Mdx.^ M<H^ ENTITLED IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF- Instructor in Charge APPROVED: HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF 167828 UlUC \ J. A/ 4y 01 UNIVERSITY of ILLINOW PREFACE In the preparation of this essay it has been the constant aim the to treat only those things which have influenced most directly lives of the people and helped to mold their plastic institutions and ideas. The home, the church, the school, and the econoraio conditions, all receive attention.