Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection: NORCOM, DR. JAMES, and FAMILY PAPERS Edenton, North Carolina

Collection: NORCOM, DR. JAMES, AND FAMILY PAPERS .P.C.?J.l-71,3 Edenton, North Carolina - 1805-1S73 Ph)'!\lcal Description: Letters and miscellaneous documents, .£• 275 items.· Acquisition: Received from Miss ·Penelope Norcom, Hertford, North Carolina, 1916-1918. Description: James Norcom, son of Miriam Standin and John Norcom, was born December 29, 1778, in Chowan County. He attended the Medical School of the University of Pennsylvania, and received his M. D. degree in 1797. He was married in 1801 to Mary Custus. They had one son, John, born 1802. They were divorced.£· 1805. James Norcom married Mary (Maria) Horniblow on July 24, 1810. Their children were James, Jr. (b. lSll), Benjamin Rush (b. 1Sl3), Caspar Wistar (b. 1818), Mary Matilda (b. 1822), Elizabeth Hannah (b. 1826), H. Standin and Abner (twins), and William Augustus B. (b. 1836). Dr. Norcom spent most of his life practicing medicine in Edenton, He served as army surgeon during War of 1812. He was member of the Board of Trustees ·or the Edenton Academy, He died in Edenton on November 9, 1850.· Dr. Norcom's early correspondence includes two letters to hie brother, Edmund, and several to Maria Horniblow and her mother, Mrs. Elizabeth Horniblow. Most of his letters are to his children, particularly to John, Rush, and Mary Matilda, beginning while they are in school, and to Elizabeth, and give ' instructions in many areas, reflecting the customs of that day, in letter writing, what to read, how to study, use of vacation, caring for their health, obedience to parents, religion, social behavior, ·marriage> etc, He also gives family and neighborhood news and occasional political· news; With his sons who are doctors or studying medicine he discusses his patients and . -

Journal of the Presbyterian Historical Society

JOURNAL OF tHE Presbyterian Historical Society. Vol. I., No. 4. Philadelphia, Pa. June A. D., 1902. THE EARLY EDITIONS OF WATTS'S HYMNS. By LOUIS F. BENSON, D. D. Not many books were reprinted more frequently during the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century than the Hymns and Spiritual Songs of Isaac Watts. Few books became more familiar, and certainly but few played a greater part in the history of our American Presbyterianism, both in its worship and in its strifes. But with all this familiarity and multiplica tion of editions, the early history, textual and bibliographical, of the hymns has remained practically unknown. This is ac counted for by the fact that by the time interest in such studies began to be awakened, the early editions of the book itself had disappeared from sight. As long ago as 1854, Peter Cunningham, when editing the Life of Watts in Johnson's Lives of the Poets, stated that "a first edition of his Hymns, 1707, is rarer than a first edition of the Pilgrim's Progress, of which it is said only one copy is known." The second edition is not less rare. The Rev. James Mearns, assistant editor of Julian's Dictionary of Hymnology, stated (The Guardian, London, January 29, 1902) that he had never seen or heard of a copy. Even now the British Museum possesses nothing earlier than the fifth edition of 1716. It has (265 ) THE LOG COLLEGE OF NESHAM1NY AND PRINCETON UNIVERSITY. By ELIJAH R. CRAVEN, D. D., LL, D. After long and careful examination of the subject, I am con vinced that while there is no apparent evidence of a legal con nection between the two institutions, the proof of their connec tion as schools of learning — the latter taking the place of the former — is complete. -

History of Neshaminy Presbyterian Church of Warwick, Hartsville

HISTORY shaming ;jr^slrgtiriHn :yjturrh v7".A.:E^-^Arioic, HARTSVILLE, BUCKS COUNTY, PA. 17^6-187^. BY • REV. DfX. TURNER. PUBLISHED BY REQUEST OF THE SESSION. PHILADELPHIA : CULBERTSON & BACHE, PRINTERS, 727 JaYNE StREET. 1876. o o CO TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE. ' Correspondence, • ' ^}. ^i" Succession of Pastors, .... xv • • • • Preface, . • f CHAPTER I. EARLY SETTLEMENT. Jamison's Location of Neshaminy Church.—Forks of Neshaminy.— Corner.—Founding of the Church.—Rev. P. Van Vleck.—Deeds and yiven by WiLiam Penn.—Holland Churches at Feasterville Richborough.—Bensalem.—Few Presbyterian Churches.—The Scotch Irish. ....•• CHAPTER II. REV. WILLIAM TENNENT. Mr. Tennent's birth and education.—His ordination in the Episco- Presbyterian pal Church.—Marriage.—He unites with the Church.—Reasons for his change of ecclesiastical relation.— Takes Residence at Bensalem, Northampton and Warminster.— " Rev. charge of the Church at Neshaminy.—The Old Side."— Grave George Whitefield visits Neshaminy.—Preaches in the § Yard.—" Log College." CHAPTER III. SONS OF REV. WILLIAM TENNENT. N. J., and Rev. Gilbert Tennent.—His pastorate at Kew^ Brunswick, character. Rev. in Philadelphia.—His death and burial.—His William Tennent, Jr.—Education.—Residence in New Bruns- wick.—The trance.—Apparent death and preparation for burial. —His recovery.—Account of his view of Heaven.—Settlement Settlement at Freehold, N. J.—Death. Rev. John Tennent.— early age. Rev. at Freehold.—Usefulness.—Death at an Charles Tennent—Ordination at Whiteclay Creek, Delaware.— with the Residence at Buckingham, Maryland.—His connection "New Side."—Mrs. Douglass. -Rev. William M. Tennent, 19 D. D. — IV CONTENTS. CHAPTER IV. ALUMNI OF LOG COLLEGE. Rev. Samuel Blair.—Settlement at Shrewsbury, N. -

Presbyterians and Revival Keith Edward Beebe Whitworth University, [email protected]

Whitworth Digital Commons Whitworth University Theology Faculty Scholarship Theology 5-2000 Touched by the Fire: Presbyterians and Revival Keith Edward Beebe Whitworth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/theologyfaculty Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Beebe, Keith Edward. "Touched by the Fire: Presbyterians and Revival." Theology Matters 6.2 (2000): 1-8. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theology at Whitworth University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Whitworth University. TTheology MMattersatters A Publication of Presbyterians for Faith, Family and Ministry Vol 6 No 2 • Mar/Apr 2000 Touched By The Fire: Presbyterians and Revival By Keith Edward Beebe St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland, Undoubtedly, the preceding account might come as a Tuesday, March 30, 1596 surprise to many Presbyterians, as would the assertion that As the Holy Spirit pierces their hearts with razor- such experiences were a familiar part of the spiritual sharp conviction, John Davidson concludes his terrain of our early Scottish ancestors. What may now message, steps down from the pulpit, and quietly seem foreign to the sensibilities and experience of present- returns to his seat. With downcast eyes and heaviness day Presbyterians was an integral part of our early of heart, the assembled leaders silently reflect upon spiritual heritage. Our Presbyterian ancestors were no their lives and ministry. The words they have just strangers to spiritual revival, nor to the unusual heard are true and the magnitude of their sin is phenomena that often accompanied it. -

A Timeline of Bucks County History 1600S-1900S-Rev2

A TIMELINE OF BUCKS COUNTY HISTORY— 1600s-1900s 1600’s Before c. A.D. 1609 - The native peoples of the Delaware Valley, those who greet the first European explorers, traders and settlers, are the Lenni Lenape Indians. Lenni Lenape is a bit of a redundancy that can be translated as the “original people” or “common people.” Right: A prehistoric pot (reconstructed from fragments), dating 500 B.C.E. to A.D. 1100, found in a rockshelter in northern Bucks County. This clay vessel, likely intended for storage, was made by ancestors of the Lenape in the Delaware Valley. Mercer Museum Collection. 1609 - First Europeans encountered by the Lenape are the Dutch: Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing under the Dutch flag, sailed up Delaware Bay. 1633 - English Captain Thomas Yong tries to probe the wilderness that will become known as Bucks County but only gets as far as the Falls of the Delaware River at today’s Morrisville. 1640 - Portions of lower Bucks County fall within the bounds of land purchased from the Lenape by the Swedes, and a handful of Swedish settlers begin building log houses and other structures in the region. 1664 - An island in the Delaware River, called Sankhickans, is the first documented grant of land to a European - Samuel Edsall - within the boundaries of Bucks County. 1668 - The first grant of land in Bucks County is made resulting in an actual settlement - to Peter Alrichs for two islands in the Delaware River. 1679 - Crewcorne, the first Bucks County village, is founded on the present day site of Morrisville. -

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb. -

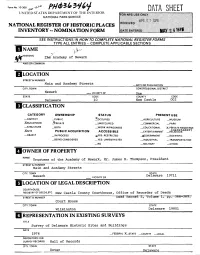

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 ^O' 1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC .The"' Academy of Newark AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Newark _ VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _3>RIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE JiSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _ REGifc^S 6 —OBJECT _ INPROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED -^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trustees of the Academy of Newark, Mr. James H. Thompson, President STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets CITY, TOWN Delaware 19711 Newark VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle County Courthouse, Office of Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Deed Record Z , Volume 366 369, Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 19801 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1974 —FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE 1LGOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Academy Square/ at the southeast corner of Main and Academy Streets, is a park, on the south side of which is the Academy of Newark building. -

A Political Biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1979 A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776 John Thomas anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation anderson, John Thomas, "A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776" (1979). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625075. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tdv7-hy77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF JOHN WITHERSPOON * L FROM 1723 TO 1776 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts *y John Thomas Anderson APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, September 1979 John Michael McGiffert (J ^ j i/u?wi yybirvjf \}vr James J. Thompson, Jr. To my parents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION....................... ill TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................... v ABSTRACT........... vi INTRODUCTION................. 2 CHAPTER I. "OUR NOBLE, VENERABLE, REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": JOHN WITHERSPOON IN SCOTLAND, 1723-1768 . ............ 5 CHAPTER II. "AN EQUAL REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": WITHERSPOON IN NEW JERSEY, 1768-1776 37 NOTES . -

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin 25

YPi AAAAAAJL 'imjij i=W AurCS'.ORAPHYOF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN t: > ' '^ \^^ -^ • ^JJ^I yfv Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/autobiographyofb00fran5 V Autobiography or Benjaa\in Tranklin Chicago W. B. CONKEY COMPANY THE IIW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY gG819^B ASTCR, LEN&X AND TfLOm HtfUNDAliONS B 1044 L LIFE or DR. FRANKLIN / My deab Sok, I HAVE amused myself with collecting some little anecdotes of my family. You may re- member the inquiries I made, when you were with me in England, among such of my rela- tions as were then living ; and the journey J undertook for that purpose. To be ac- quainted with the particulars of my parent- age and life, many of which are unknown to you, I flatter myself will afford the same pleasure to you as to me. I shall relate them upon paper : it will be an agreeable employ- ment of a week's uninterrupted leisure, which I promise myself during my present retire- ment in the country. There are also other motives which induce me to the undertaking. 4 3YS5 a 4 LI Ft: OF DR.. FRANKLIlSf. From the bosom of poverty and obscurity, in which I drew my first breath, and spent my earliest years, I have raised myself to a state of opulence and to some degree of celebrity in the world. A constant good fortune has attended me through every period of life to my present advanced age ; and my descend- ants may be desirous of learning what were the means of which I made use, and which, thanks to the assisting hand of Providence, have proved so eminently successful. -

NOTES and DOCUMENTS "A Very Diffused Disposition:" Dissecting

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS "A Very Diffused Disposition:" Dissecting Schools in Philadelphia, 1823-1825 In 1813 Benjamin Rush, Professor of Theory and Practice of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, died of pneumonia. His death was universally mourned for Rush had been a leading political statesman as well as a renowned physician. "Another of our friends of seventy-six is gone, my dear Sir, another of the co-signers of the Independence of our country. And a better man than Rush could not have left us, more benevolent, more learned, of finer genius, or more honest," wrote Thomas Jefferson to John Adams.l Rush's passing prefigured the end of an era in American medicine. Rush was the last great exponent of the speculative theories of medicine. He believed that disease corresponded to a state of the body; if the victim were excited or feverish, he could only be cured by depletion —usually blood-letting—and if he were debilitated, then stimulants— wine, brandy, or opium—should be applied to bring the body back to a normal state.2 Only ten years after Rush's death considerable, although not unan- imous, skepticism was being voiced about the Value of metaphysical systems. Ironically, in 1823 Nathaniel Chapman, Rush's successor, bore the brunt of the criticism. Chapman had developed a solidistic theory which explained the action of drugs—for instance, diuretics—as affecting first the stomach, then through "sympathy. .the absorbents or kidneys, according to the affinity of the article to one or the other of these parts." Gouveneur Emerson, a physician on the Philadelphia Board of Health, after reading Francois Magendie's experiments on 1 Jefferson to Adams, 27 May 1813, in Paul Wilstach, eti., Correspondence of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, 1812-1826 (Indianapolis, 1825), 48. -

Knowing Doing

Knowing oing &D. C S L e w i S i n S t i t u t e David Brainerd: “A Constant Stream” by David B. Calhoun, Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri This article originally appeared in the Summer 2011 issue of Knowing & Doing. avid Brainerd died on October 9, 1747, in Jona- lege, and a few months later so than Edwards’s home in Northampton, Mas- did Gilbert Tennent. Because Dsachusetts. In what Edwards saw as a singular of the strong revival preaching act of God’s providence, Brainerd had been persuaded of these ministers, Brainerd, by friends not to destroy his diary. Instead, he had put writes Jonathan Edwards, ex- it in Edwards’s hands to dispose of as “would be most perienced “much of God’s gra- for God’s glory and the interest of religion.” cious presence, and of the lively Jonathan Edwards edited the diary, added his own actings of true grace” but also comments, and published it in 1749. Later editions also was influenced by that “intem- David B. Calhoun contained Brainerd’s missionary journal. According to perate, indiscreet zeal, which Marcus Loane: was at that time too prevalent.” When Brainerd criti- cized one of the college tutors and the rector for their The diary is a remarkable record of the interior life of opposition to the revival, he was expelled. Neither his the soul, and its entries still throb with the tremendous own apology nor Jonathan Edwards’s appeal moved earnestness of a man whose heart was aflame for God. -

At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin: a Brief History of the Library Company of Philadelphia

At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin: A Brief History of The Library Company of Philadelphia On July 1, 1731, Benjamin Franklin and a number of his fellow members of the Junto drew up "Articles of Agreement" to found a library. The Junto was a discussion group of young men seeking social, economic, intellectual, and political advancement. When they foundered on a point of fact, they needed a printed authority to settle the divergence of opinion. In colonial Pennsylvania at the time there were not many books. Standard English reference works were expensive and difficult to obtain. Franklin and his friends were mostly mechanics of moderate means. None alone could have afforded a representative library, nor, indeed, many imported books. By pooling their resources in pragmatic Franklinian fashion, they could. The contribution of each created the book capital of all. Fifty subscribers invested forty shillings each and promised to pay ten shillings a year thereafter to buy books and maintain a shareholder's library. Thus "the Mother of all American Subscription Libraries" was established. A seal was decided upon with the device: "Two Books open, Each encompass'd with Glory, or Beams of Light, between which water streaming from above into an Urn below, thence issues at many Vents into lesser Urns, and Motto, circumscribing the whole, Communiter Bona profundere Deum est." This translates freely: "To pour forth benefits for the common good is divine." The silversmith Philip Syng engraved the seal. The first list of desiderata to stock the Tin Suggestion shelves was sent to London on March 31, 1732, and by autumn that Box, ca.