ADB-Financed Western Regional Roads Development Project Phase II ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

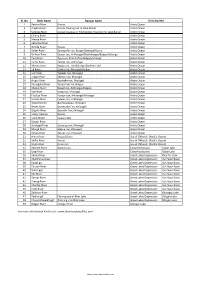

List of Rivers of Mongolia

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Key Sites for Key Sites for Conservation

Directory of Important Bird Areas in Mongolia: KEY SITES FOR CONSERVATION A project of In collaboration with With the support of Printing sponsored by Field surveys supported by Directory of Important Bird Areas in Mongolia: KEY SITES FOR CONSERVATION Editors: Batbayar Nyambayar and Natsagdorj Tseveenmyadag Major contributors: Ayurzana Bold Schagdarsuren Boldbaatar Axel Bräunlich Simba Chan Richard F. A. Grimmett and Andrew W. Tordoff This document is an output of the World Bank study Strengthening the Safeguard of Important Areas of Natural Habitat in North-East Asia,fi nanced by consultant trust funds from the government of Japan Ulaanbaatar, January 2009 An output of: The World Bank study Strengthening the Safeguard of Important Areas of Natural Habitat in North-East Asia,fi nanced by consultant trust funds from the government of Japan Implemented by: BirdLife International, the Wildlife Science and Conservation Center and the Institute of Biology of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences In collaboration with: Ministry of Nature, Environment and Tourism Supporting organisations: WWF Mongolia, WCS Mongolia Program and the National University of Mongolia Editors: Batbayar Nyambayar and Natsagdorj Tseveenmyadag Major contributors: Ayurzana Bold, Schagdarsuren Boldbaatar, Axel Bräunlich, Simba Chan, Richard F. A. Grimmett and Andrew W. Tordoff Maps: Dolgorjav Sanjmyatav, WWF Mongolia Cover illustrations: White-naped Crane Grus vipio, Dalmatian Pelican Pelecanus crispus, Whooper Swans Cygnus cygnus and hunters with Golden Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (Batbayar Nyambayar); Siberian Cranes Grus leucogeranus (Natsagdorj Tseveenmyadag); Saker Falcons Falco cherrug and Yellow-headed Wagtail Motacilla citreola (Gabor Papp). ISBN: 978-99929-0-752-5 Copyright: © BirdLife International 2009. All rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged Suggested citation: Nyambayar, B. -

Infrastructure Strategy Review Making Choices in Provision of Infrastructure Services

MONGOLIA Infrastructure Strategy Review Making Choices in Provision of Infrastructure Services S. Rivera East Asia & Pacific The World Bank Government of Mongolia: Working Group Technical Donors Meeting October, 2006. 1 Mongolia: Infrastructure Strategy The Process and Outputs Factors Shaping Infrastructure Strategy Demand Key Choices to discuss this morning 2 Process and Outcome The Process – An interactive process, bringing together international practices: Meeting in Washington, March 2005. Field work in the late 2005. Preparation of about 12 background notes in sector and themes, discussed in Washington on June 2006. Submission of final draft report in November, 2006 Launching of Infrastructure Strategy report in a two day meeting in early 2007. Outcome A live document that can shape and form policy discussions on PIP, National Development Plan, and Regional Development Strategy….it has been difficult for the team to assess choices as well. 3 Factors Shaping the IS • Urban led Size and Growth of Ulaanbaatar and Selected Aimag (Pillar) Centers Size of the Circle=Total Population ('000) Infrastructure 6% 5% 869.9 Investments ) l 4% ua nn 3% a Ulaanbaatar (%, 2% h t Darkhan w Erdenet o 1% r G n 0% o i -10 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 at l -1% Choibalsan Kharkhorin opu Ondorkhaan P -2% Khovd Uliastai -3% Zuunmod -4% Share of Total Urban Population (%) 4 Factors Shaping the IS: Connectivity, with the World and in Mongolia Khankh Khandgait Ulaanbaishint Ereentsav Khatgal Altanbulag ULAANGOM Nogoonnuur UVS KHUVSGUL Tsagaannuur ÒýñTes -

INFLUENCE of SOIL-ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS on VEGETATION ZONATION in a WESTERN MONGOLIAN LAKE SHORE- SEMI-DESERT ECOTONE with 6 Figures, 4 Tables and 4 Photos

72 Erdkunde Band 61/2007 INFLUENCE OF SOIL-ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS ON VEGETATION ZONATION IN A WESTERN MONGOLIAN LAKE SHORE- SEMI-DESERT ECOTONE With 6 figures, 4 tables and 4 photos ANDREA STRAUSS and UDO SCHICKHOFF Keywords: Vegetation geography, soil geography, environmental change, Central Asia, semidesert environments Keywords: Vegetationsgeographie, Bodengeographie, Umweltforschung, Zentralasien, aride Räume Zusammenfassung: Der Einfluss bodenökologischer Bedingungen auf die Vegetationszonierung in einem Seeufer-Halb- wüsten-Ökoton der westlichen Mongolei Das Becken der Großen Seen in der Westmongolei ist geprägt von ausgedehnten Wüsten-, Halbwüsten- und Steppen- arealen sowie von Seen und umgebenden einzigartigen Feuchtgebieten. Diese Feuchtgebiete sind bedeutende Elemente der Landschaftsökosysteme semi-arider und arider Räume. Andererseits ist die Kenntnis selbst grundlegender Ökosystemkompo- nenten wie Vegetation und Böden noch sehr lückenhaft. Das Ziel der vorliegenden landschaftsökologischen Studie entlang eines Seeufer-Halbwüsten-Ökotons war es, das klein- räumige Muster von Standortfaktoren entlang eines ausgeprägten Umweltgradienten sowie den Einfluss dieses Musters auf die Vegetationszonierung zu analysieren. Um die Veränderungen in dem Übergangsbereich zwischen aquatischen und terres- trischen Lebensräumen adäquat zu erfassen, wurden die Daten mit einem Transekt-Ansatz aufgenommen. Pflanzengesell- schaften wurden nach der Braun-Blanquet-Methode klassifiziert. Die Vegetations- und Bodendaten wurden einer Detrended Correspondence -

Land Use and Land Tenure in Mongolia: a Brief History and Current Issues Maria E

Land Use and Land Tenure in Mongolia: A Brief History and Current Issues Maria E. Fernandez-Gimenez Maria E. Fernandez-Gimenez is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Forest, Rangeland, and Watershed Stewardship at Colorado State University. She received her PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 1997 and has conducted research in Mongolia since 1993. Her current areas of research include pastoral development policy; community-based natural resource management; traditional and local ecological knowledge; and monitoring and adaptive management in rangeland ecosystems. strategies have not changed greatly; mobile and flexible grazing Abstract—This essay argues that an awareness of the historical relation- ships among land use, land tenure, and the political economy of Mongolia strategies adapted to cope with harsh and variable production is essential to understanding current pastoral land use patterns and policies conditions remain the cornerstone of Mongolian pastoralism. in Mongolia. Although pastoral land use patterns have altered over time in Similarly, although land tenure regimes have evolved towards response to the changing political economy, mobility and flexibility remain increasingly individuated tenure over pastoral resources, hallmarks of sustainable grazing in this harsh and variable climate, as do the communal use and management of pasturelands. Recent changes in Mongolia’s pasturelands continue to be held and managed as common political economy threaten the continued sustainability of Mongolian pastoral property resources in most locations, although these institutions systems due to increasing poverty and declining mobility among herders and have been greatly weakened in the past half century. The most the weakening of both formal and customary pasture management institu- recent changes in Mongolia’s political economy threaten the tions. -

The Magic of the Mongolian West

Magie de l'ouest Mongol Jours: 14 Prix: 1550 EUR Vol international non inclus Confort: Difficulté: Aventure, exploration et expédition Hors des sentiers battus Randonnée Minorité ethnique Aux confins de l'Asie Centrale, des peuplades Kazakhs vivent en harmonie avec leurs coutumes ancestrales. Sommets enneigés, glaciers, lacs cristallins et vallées luxuriantes, l'Altai Mongol est une des régions les plus reculées du Monde. Un circuit alternant découverte en jeep et journées de randonnée, pour les personnes souhaitant découvrir l'ouest du pays à un rythme modéré. Jour 1. Oulan-Bator, arrivée et visite de la ville Accueil par notre chauffeur à votre sortie de l'aéroport. Transfert à votre hôtel, installation et repos. Rendez-vous à midi à votre hôtel avec votre guide, qui vous amènera déjeuner dans le restaurant de votre choix. Plongeons au coeur de l'histoire mongole, au superbe musée d'histoire nationale. Trois étages d'un passé riche et glorieux, violent et noble, depuis la préhistoire jusqu'à la période soviétique, en passant bien sûr par la création du grand empire mongol par Gengis Khan. Oulan Bator Balade dans le centre ville d'Oulan-Bator. Découverte de la place centrale Gengis Khan, et du Parlement. À 18h00, spectacle traditionnel mongol au Tumen Ekh : danses folkloriques, contorsion et bien sûr khoomi, le chant diphonique. Hébergement Hôtel Nine Jour 2. Vol pour le far west mongol Oulan Bator - Khovd Nous quittons la trépidante capitale mongole pour embarquer sur un vol domestique à destination de Khovd. Khovd fut un centre commercial important situé au nord de la route de la soie, qui avait tissé des liens avec la Russie et la Chine. -

Western Mongolia

© Lonely Planet Publications 219 WESTERN MONGOLIA Western Mongolia With its raw deserts, glacier-wrapped mountains, shimmering salt lakes and hardy culture of nomads, falconry and cattle rustling, western Mongolia is a timeless place that fulfils many romantic notions of the classic ‘Central Asia’. Squeezed between Russia, Kazakhstan, China and the Mongol heartland, this region has been a historical transition zone of endless cultures, the legacy of which is a patchwork of peoples including ethnic Kazakhs, Dorvods, Khotons, Myangads and Khalkh Mongols. The Mongol Altai Nuruu forms the backbone of the region, a rugged mountain range that creates a natural border with both Russia and China. It contains many challenging and popular peaks for mountain climbers, some over 4000m, and is the source of fast-flowing rivers, most of which empty into desert lakes and saltpans. The region’s wild landscape and unique mix of cultures is known among adventure travel- lers and a small tourist infrastructure has been created to support them. Bayan-Ölgii leads the pack with its own clique of tour operators and drivers prepared to shuttle visitors to the mountains. But while aimag capitals are tepidly entering the 21st century, most of the region remains stuck in another age – infrastructure is poor and old-style communist think- ing is the norm among local officials. Despite the hardships, western Mongolia’s attractions, both natural and cultural, are well worth the effort. With time and flexibility, the region may well be the highlight of your trip. HIGHLIGHTS -

MONGOLIA: Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized

MONGOLIA: Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Acknowledgements This Mongolia Strategic Country Diagnostic was led by Samuel Freije-Rodríguez (lead economist, GPV02) and Tuyen Nguyen (resident representative, IFC Mongolia). The following World Bank Group experts participated in different stages of the production of this diagnostics by providing data, analytical briefs, revisions to several versions of the document, as well as participating in several internal and external seminars: Rabia Ali (senior economist, GED02), Anar Aliyev (corporate governance officer, CESEA), Indra Baatarkhuu (communications associate, EAPEC), Erdene Badarch (operations officer, GSU02), Julie M. Bayking (investment officer, CASPE), Davaadalai Batsuuri (economist, GMTP1), Batmunkh Batbold (senior financial sector specialist, GFCP1), Eileen Burke (senior water resources management specialist, GWA02), Burmaa Chadraaval (investment officer, CM4P4), Yang Chen (urban transport specialist, GTD10), Tungalag Chuluun (senior social protection specialist, GSP02), Badamchimeg Dondog (public sector specialist, GGOEA), Jigjidmaa Dugeree (senior private sector specialist, GMTIP), Bolormaa Enkhbat (WBG analyst, GCCSO), Nicolaus von der Goltz (senior country officer, EACCF), Peter Johansen (senior energy specialist, GEE09), Julian Latimer (senior economist, GMTP1), Ulle Lohmus (senior financial sector specialist, GFCPN), Sitaramachandra Machiraju (senior agribusiness specialist, -

Impacts of Late Quaternary Environmental Change on the Long-Tailed Ground Squirrel (Urocitellus Undulatus) in Mongolia

ZOOLOGICAL RESEARCH Impacts of late Quaternary environmental change on the long-tailed ground squirrel (Urocitellus undulatus) in Mongolia Bryan S. McLean1,*, Batsaikhan Nyamsuren2, Andrey Tchabovsky3, Joseph A. Cook4 1 University of Florida, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA 2 Department of Biology, School of Arts and Sciences, National University of Mongolia, Ulaan Baatar 11000, Mongolia 3 Laboratory of Population Ecology, A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Moscow 119071, Russia 4 University of New Mexico, Department of Biology and Museum of Southwestern Biology, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA ABSTRACT of range shifts into these lowland areas in response to Pleistocene glaciation and environmental change, Impacts of Quaternary environmental changes on followed by upslope movements and mitochondrial mammal faunas of central Asia remain poorly lineage sorting with Holocene aridification. Our study understood due to a lack of comprehensive illuminates possible historical mechanisms responsible phylogeographic sampling for most species. To for U. undulatus genetic structure and contributes to help address this knowledge gap, we conducted a framework for ongoing exploration of mammalian the most extensive molecular analysis to date of response to past and present climate change in central the long-tailed ground squirrel (Urocitellus undulatus Asia. Pallas 1778) in Mongolia, a country that comprises Keywords: Central Asia; Gobi Desert; Great Lakes the southern core of this species’ range. Drawing on Depression; Mongolia; Phylogeography material from recent collaborative field expeditions, we genotyped 128 individuals at two mitochondrial INTRODUCTION genes (cytochrome b and cytochrome oxidase I; Urocitellus undulatus Pallas 1778 is a charismatic, 1 797 bp total). Phylogenetic inference supports the medium-bodied ground-dwelling sciurid distributed across existence of two deeply divergent infraspecific lineages central Asia, including portions of Siberia, Mongolia, (corresponding to subspecies U. -

438962 1 En Bookbackmatter 213..218

Index A Average temperature, 4, 53, 55, 57, 87, 111, 162, 185 Accumulation, 12, 26, 27, 33, 44, 66, 109, 113, 140, 141, Average wind speed, 64 144–146, 152, 155, 162 Achit lake, 37, 116, 165, 208 Active layer, 122, 124–126, 130 B Active layer thickness, 124–126 Baatarkhaihan, 35 Adaatsag, 46 Baga Bogd, 3, 38, 43, 188 Agricultural land, 136, 195–199 Baga Buural, 47 Airag lake, 91, 208 Baga Gazriin Chuluu, 46, 47 Air temperature variation, 111 Baga Khavtag, 45 Aj Bogd, 35, 190 Baga Khentii, 39, 80, 110 Alag khairhan, 35 Baga Uul, 47 Alasha Gobi, 163, 165 Baishin Tsav, 46 Algae, 161, 166 Baitag Bogd, 45 Alluvial fans and sediments, 45, 46 Baruun Khuurai depression, 28, 158, 181 Alluvial-proluvial plains, 27, 29 Baruun Saikhan, 33, 43 Alluvial soils, 145, 157 Baruunturuun, 68, 136 Alpine belts, 66, 171, 185 Bayan, 3, 7, 34–36, 40, 69, 79, 88, 89, 91, 106, 109, 113 Alpine-type high mountains, 32 Bayanbor, 43 Alpine type relief, 44 Bayan Bumbun Ranges, 35 Altai region, 5, 28, 35, 42, 65, 144 Bayankhairhan, 39 Altai-Sayan ecoregion, 210 Bayantsagaan, 42, 43, 47, 49 Altai Tavan Bogd, 24, 35 Bayan-Ulgii, 7, 69, 113 Altankhukhii, 35 Biological diversity, 182 Altan Ulgii, 39 Birds, 161, 162, 169–175, 207, 208 Altitudinal belts, 6, 163, 177, 182–185, 187, 190, 192 Bogd, 3, 11, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 49, 101–103, 106, 181, Angarkhai, 38 188, 204, 208 Animal, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 16, 33, 72, 145, 169, 171, 172, Bogd Ulaan, 49 197, 205 Boreal, 6, 163, 164, 187, 210 Annual precipitation, 53, 60, 61, 71, 86, 92, 121, 186, Bor Khairhan, 39 188, 189, 192 Borzon -

PRESENT SITUATION of KAZAKH-MONGOLIAN COMMUNITY Ts.Baatar, Ph.D

The Mongolian Journal of International Affairs Number 8-9, 2002 PRESENT SITUATION OF KAZAKH-MONGOLIAN COMMUNITY Ts.Baatar, Ph.D (Mongolia) The name and identity “kazakh” emerged in the sixteenth century, when a Kazakh Khanate was founded in today’s Kazakhstan. The Kazakh aristocrats trace their origin directly to Chinggis Khan or his sons. In the sixteenth century, ethnic Kazakhs were historically divided into three clans or zhuzes: The senior zhuz, the middle zhuz, and the junior zhuz. Once under the rule of the Oirad Mongols in the seventeenth to eighteen centuries, some middle zhuz Kazakhs later moved into Jungaria. The Kazakhs in Mongolia are mostly Abak-kerei and Naiman Kazakhs who settled in the Altai and Khovd regions, where they rented pasture from the lords of Mongolia during the 1860s according to Tarbagatai Protokol between Russia and Qing Dynasty. The nomads came to graze their sheep on the high mountain pastures during the summer, and spent the winter in Kazakhstan or Xinjiang province in China. After the Mongolian revolution in 1921, a permanent border was drawn by agreement between China, Russia and Mongolia, but the Kazakhs remained nomadic until the 1930s, crossing the border at their own will.1 The word kazakh is said to mean ‘free warrior’ or ‘steppe roamer’. Kazakhs trace their roots to the fifteenth century, when rebellious kinsmen of an Uzbek Khan broke away and settled in present-day Kazakhstan. In Mongolia, more than in Kazakhstan, Kazakh women wear long dresses with stand-up collars, or brightly decorated velvet waistcoats and heavy jewelry. The men still wear baggy shirts and trousers, sleeveless jackets, wool or cotton robes, and a skullcap or a high, tasseled felt hat.2 In 1923 the Mongolian Kazakh population numbered 1,870 households and 11,220 people.3 Subsequently, many more have come to Mongolia from 3 Paul Greenway, Robert Story and Gobriel Lafitte (1997), Mongolia (Lonely Planet Publications), p.231. -

Argali (Ovis Ammon) Conservation in Western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2003 Argali (Ovis ammon) conservation in western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan Ryan L. Maroney The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Maroney, Ryan L., "Argali (Ovis ammon) conservation in western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan" (2003). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6497. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6497 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes” or "No” and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author’s Signature; Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 ARGALI ipvis ammon) CONSERVATION IN WESTERN MONGOLIA AND THE ALTAI SAYAN by Ryan L. Maroney B.A., New College, Sarasota, Florida, 1999 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The University of Montana 2003 Approved by Chairperson Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP37298 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.