Briefing Note on Mongolia Briefing Note on Mongolia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

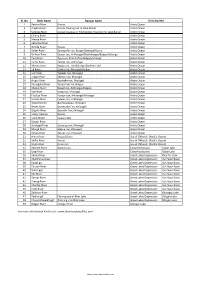

List of Rivers of Mongolia

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

INFLUENCE of SOIL-ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS on VEGETATION ZONATION in a WESTERN MONGOLIAN LAKE SHORE- SEMI-DESERT ECOTONE with 6 Figures, 4 Tables and 4 Photos

72 Erdkunde Band 61/2007 INFLUENCE OF SOIL-ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS ON VEGETATION ZONATION IN A WESTERN MONGOLIAN LAKE SHORE- SEMI-DESERT ECOTONE With 6 figures, 4 tables and 4 photos ANDREA STRAUSS and UDO SCHICKHOFF Keywords: Vegetation geography, soil geography, environmental change, Central Asia, semidesert environments Keywords: Vegetationsgeographie, Bodengeographie, Umweltforschung, Zentralasien, aride Räume Zusammenfassung: Der Einfluss bodenökologischer Bedingungen auf die Vegetationszonierung in einem Seeufer-Halb- wüsten-Ökoton der westlichen Mongolei Das Becken der Großen Seen in der Westmongolei ist geprägt von ausgedehnten Wüsten-, Halbwüsten- und Steppen- arealen sowie von Seen und umgebenden einzigartigen Feuchtgebieten. Diese Feuchtgebiete sind bedeutende Elemente der Landschaftsökosysteme semi-arider und arider Räume. Andererseits ist die Kenntnis selbst grundlegender Ökosystemkompo- nenten wie Vegetation und Böden noch sehr lückenhaft. Das Ziel der vorliegenden landschaftsökologischen Studie entlang eines Seeufer-Halbwüsten-Ökotons war es, das klein- räumige Muster von Standortfaktoren entlang eines ausgeprägten Umweltgradienten sowie den Einfluss dieses Musters auf die Vegetationszonierung zu analysieren. Um die Veränderungen in dem Übergangsbereich zwischen aquatischen und terres- trischen Lebensräumen adäquat zu erfassen, wurden die Daten mit einem Transekt-Ansatz aufgenommen. Pflanzengesell- schaften wurden nach der Braun-Blanquet-Methode klassifiziert. Die Vegetations- und Bodendaten wurden einer Detrended Correspondence -

Impacts of Late Quaternary Environmental Change on the Long-Tailed Ground Squirrel (Urocitellus Undulatus) in Mongolia

ZOOLOGICAL RESEARCH Impacts of late Quaternary environmental change on the long-tailed ground squirrel (Urocitellus undulatus) in Mongolia Bryan S. McLean1,*, Batsaikhan Nyamsuren2, Andrey Tchabovsky3, Joseph A. Cook4 1 University of Florida, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA 2 Department of Biology, School of Arts and Sciences, National University of Mongolia, Ulaan Baatar 11000, Mongolia 3 Laboratory of Population Ecology, A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Moscow 119071, Russia 4 University of New Mexico, Department of Biology and Museum of Southwestern Biology, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA ABSTRACT of range shifts into these lowland areas in response to Pleistocene glaciation and environmental change, Impacts of Quaternary environmental changes on followed by upslope movements and mitochondrial mammal faunas of central Asia remain poorly lineage sorting with Holocene aridification. Our study understood due to a lack of comprehensive illuminates possible historical mechanisms responsible phylogeographic sampling for most species. To for U. undulatus genetic structure and contributes to help address this knowledge gap, we conducted a framework for ongoing exploration of mammalian the most extensive molecular analysis to date of response to past and present climate change in central the long-tailed ground squirrel (Urocitellus undulatus Asia. Pallas 1778) in Mongolia, a country that comprises Keywords: Central Asia; Gobi Desert; Great Lakes the southern core of this species’ range. Drawing on Depression; Mongolia; Phylogeography material from recent collaborative field expeditions, we genotyped 128 individuals at two mitochondrial INTRODUCTION genes (cytochrome b and cytochrome oxidase I; Urocitellus undulatus Pallas 1778 is a charismatic, 1 797 bp total). Phylogenetic inference supports the medium-bodied ground-dwelling sciurid distributed across existence of two deeply divergent infraspecific lineages central Asia, including portions of Siberia, Mongolia, (corresponding to subspecies U. -

Palaeoclimate, Glacier and Treeline Reconstruction Based On

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2018 Palaeoclimate, glacier and treeline reconstruction based on geomorphic evidences in the Mongun-Taiga massif (south-eastern Russian Altai) during the Late Pleistocene and Holocene Ganyushkin, Dmitry ; Chistyakov, Kirill ; Volkov, Ilya ; Bantcev, Dmitry ; Kunaeva, Elena ; Brandová, Dagmar ; Raab, Gerald ; Christl, Marcus ; Egli, Markus Abstract: Little is known about the extent of glaciers and dynamics of the landscape in south-eastern Russian Altai. The effects of climate-induced fluctuations of the glaciers and the upper treeline of the Mongun-Taiga mountain massif were, therefore, reconstructed on the basis of in-situ, multiannual observations, geomorphic mapping, radiocarbon and surface exposure dating, relative dating (such as Schmidthammer and weathering rind) techniques and palaeoclimate-modelling. During the maximal advance of the glaciers, their area was 26-times larger than now and the equilibrium line of altitude (ELA) was about 800m lower. Assuming that the maximum glacier extent took place during MIS 4, then the average summer temperatures were 2.7℃ cooler than today and the amount of precipitation 2.1 times higher. Buried wood trunks by a glacier gave ages between 60 and 28 cal ka BP and were found 600-700m higher than the present upper treeline. This evidences a distinctly elevated treeline during MIS 3a and c. With a correction for tectonics we reconstructed the summer warming to have been between 2.1 and 3.0℃. During MIS 3c, the glaciated area was reduced to less than 0.5 km² with an increase of the ELA of 310-470m higher than today. -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- - 1. Name and contact details of the compiler of this form *: Full name: Mr. B. Buyantsog and Dr. Gombobaatar EAAF SITE CODE FOR OFFICE USE ONLY: Sundev Institution/agency: Khan Huhiin Nuruu Protected Area and Administration Mongolian Ornithological Society. -

PDF Altai-Sayan Ecoregion Conservation Strategy

Altai-Sayan Ecoregion Conservation Strategy FINAL DRAFT VERSION, approved by the Altai-Sayan Steering Committee on 29 June 2012, considering the amendments and comments made during the teleconference of 29 June 2012, as described in the meetings notes of that meeting COLOFON Altai-Sayan Ecoregion Conservation Strategy Full Version © WWF, July 2012 Cover photo: Desert steppe Tuva region (Hartmut Jungius/ WWF-Canon) ii Table of Contents Contribution to WWF Global Conservation Programme .................................................................................................................. 1 Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 1- Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 2- Outlining the Altai-Sayan Ecoregion ............................................................................................................................................. 9 2.1 Background ................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Glaciers, Permafrost and Lake Levels at the Tsengel Khairkhan Massif, Mongolian Altai, During the Late Pleistocene and Holocene

Article Glaciers, Permafrost and Lake Levels at the Tsengel Khairkhan Massif, Mongolian Altai, During the Late Pleistocene and Holocene Michael Walther 1,*, Avirmed Dashtseren 1, Ulrich Kamp 2, Khurelbaatar Temujin 1, Franz Meixner 3, Caleb G. Pan 4 and Yadamsuren Gansukh 1 1 Institute of Geography and Geoecology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, P.O.B. 361, Ulaanbaatar 14192, Mongolia; [email protected] (A.D.); [email protected] (K.T.); [email protected] (Y.G.) 2 Department of Geography, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Atmospheric Chemistry, Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, 55128 Mainz, Germany; [email protected] 4 Systems Ecology Program, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +976-9908-7055 Received: 31 May 2017; Accepted: 11 August 2017; Published: 16 August 2017 Abstract: Understanding paleo—and recent environmental changes and the dynamics of individual drivers of water availability is essential for water resources management in the Mongolian Altai. Here, we follow a holistic approach to uncover changes in glaciers, permafrost, lake levels and climate at the Tsengel Khairkhan massif. Our general approach to describe glacier and lake level changes is to combine traditional geomorphological field mapping with bathymetric measurements, satellite imagery interpretation, and GIS analyses. We also analysed climate data from two nearby stations, and measured permafrost temperature conditions at five boreholes located at different elevations. We identified four glacial moraine systems (M4-M1) and attribute them to the period from the penultimate glaciation (MIS 4/5) until the Little Ice Age (MIS 1). -

Nota Lepidopterologica

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nota lepidopterologica Jahr/Year: 2012 Band/Volume: 35 Autor(en)/Author(s): Yakovlev Roman V. Artikel/Article: Checklist of Butterflies (Papilionoidea) of the Mongolian Altai Mountains, including descriptions of new taxa 51-96 ©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; download unter http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ und www.zobodat.at Nota lepi. 35(1): 51-96 51 Checklist of Butterflies (Papilionoidea) of the Mongolian Altai Mountains, including descriptions of new taxa Roman V. Yakovlev Ul. Chkalova 34-2, Barnaul, RUS-656038, Russia; [email protected] Received May 201 1; reviews returned 3 October 201 1; accepted 7 February 2012. Subject Editor: Jadranka Rota. Abstract. A checklist of Papilionoidea of the Mongolian Altai is presented. Several new taxa {Neolycaena sapozhnikovi sp. n., Plebejus germani sp. n., P. anikini sp. n., P. idas shadzgat ssp. n., Erebia przhevals- kii sp. n., E. chastilovi nomada ssp. n., Hyponephele lycaon dmithevae ssp. n., and H. lycaon kerzhneri ssp. n.) are described. Zoogeographical demarcation of the Mongolian Altai (within the limits of Mon- golia) is presented. Introduction The Mongolian Altai is a mountain system in Mongolia and China. It stretches ap- proximately 1000 km from the northwest to the southeast and its width varies from 300 km in the northwest to 150 km in the southeast. It reaches altitude of 4362 m (Mt. Munkh-Khajrkhan-Ula) and consists of several parallel ridges, separated by longitu- dinal tectonic valleys. The summits are mostly plateau-like, with cirque and cornice glaciers (the largest one being Potanin Glacier) on their crests. -

Bird Red List and Its Future Development in Mongolia S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Halle-Wittenberg Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 2012 Bird Red List and Its Future Development in Mongolia S. Gombobaatar National University of Mongolia, [email protected] D. Samiya National University of Mongolia Jonathan M. Baillie Zoologial Society of London, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol Part of the Animal Law Commons, Animal Studies Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Ornithology Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Gombobaatar, S.; Samiya, D.; and Baillie, Jonathan M., "Bird Red List and Its Future Development in Mongolia" (2012). Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298. 18. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -

A Country Water Security Assessment for Mongolia

Overview of Mongolia’s Water Resources System and Management A Country Water Security Assessment This publication evaluates water security in Mongolia and provides analyses based from other documents and studies for a multidimensional overview of the country’s water resources system and management. It recommends a path forward based on integrated water resources management as well as national and local institutional development, through a targeted investment program. The assessment is adapted from the analytical framework introduced in the Asian Water Development Outlook, a series of reports produced by the Asian Development Bank and the Asia-Pacific Water Forum. About the Asian Development Bank ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty. Established in 1966, it is owned by 68 members —49 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. OVERVIEW OF MONGOLIA’S WATER RESOURCES SYSTEM AND MANAGEMENT A COUNTRY WATER SECURITY ASSESSMENT JULY 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK www.adb.org OVERVIEW OF MONGOLIA’S WATER RESOURCES SYSTEM AND MANAGEMENT A COUNTRY WATER SECURITY ASSESSMENT JULY 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2020 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 8632 4444; Fax +63 2 8636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2020. ISBN 978-92-9262-285-5 (print), 978-92-9262-286-2 (electronic), 978-92-9262-287-9 (ebook) Publication Stock No. -

Limnological Aspects of the Uvs-Nuur-Basin in Northwest Mongolia

Fakultt Umweltwissenschaften Limnological aspects of the Uvs Nuur Basin in northwest Mongolia Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) vorgelegt von Dipl.-Biol. Markus Paul geb. 14.03.1968 Gutachter: Herr Prof. Dr. Dietrich Borchardt Technische Universitt Dresden Frau Prof. Dr. Brigitte Nixdorf Brandenburgische Technische Universitt Cottbus Dresden, 12. November 2012 Erklrung des Promovenden Die bereinstimmung dieses Exemplars mit dem Original der Dissertation zum Thema: „Limnological aspects of the Uvs Nuur Basin in northwest Mongolia“ wird hiermit besttigt. Dresden, 12.11.2012 Ort, Datum ……………………………………….…. Unterschrift (Vorname Name) 2 Limnological aspects of the Uvs Nuur Basin in northwest Mongolia Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) an der Fakultät Umweltwissenschaften der Technischen Universität Dresden vorgelegt von Diplombiologe Markus Paul Dresden, 12. November 2012 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Dietrich Borchardt Prof. Dr. Brigitte Nixdorf This work was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; grants UH 54/2-1, HO 1778/1-2 and HO 1778/1-3) and Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ; contract No. 81011694), which is gratefully acknowledged. Table of Contents Acknowledgments.........................................................................................................................................................ii Abstract..........................................................................................................................................................................iii -

WESTERN EXPLORER 14 Days Including Free City Walking Tour Flights from Uliastai to UB (Day 14) Limited to Tuesday and Friday Departures

WESTERN EXPLORER 14 Days including free city walking tour Flights from Uliastai to UB (Day 14) limited to Tuesday and Friday departures ‘Local touch, dependability, professionalism and attention to detail. There was a real difference between the experiences of other tourists that we encountered and ours. Every point of comparison was a big plus for EL. The way the tour was structured, the vehicle, the EL team, the places, the families, the limited number of driving hours, the camping spots, the feeling of remoteness of the lakes depression … the list goes on. Many times we said to each other how glad we were to have chosen the right company. ‘ Teo Marinska, Western Explorer, 2017 This is a customisable trip. It is adaptable, giving you the freedom to build a unique and personal trip for your chosen date. Upgrade your accommodation for all - or just part - of your trip, slow down the pace with few extra nights here and there or add a few more active adventures along the way. Written by Jess! - Eternal Landscapes 2018 Page !1 Our Western Explorer In Brief Mongolia’s landscapes are powerful and immense and nowhere in Mongolia do the landscapes get more powerful than in the western provinces of Bayan Ölgii, Uvs, and Zavkhan. What also makes this region so unique is that it is rare to find such a variety of biological diversity (ecosystems include semi-desert, interconnected shallow lakes, dunes, steppe grasslands, forests and mountains) in such proximity. This closeness of diversity is matched by few other places in the world. This region makes the ultimate road trip - travelling and camping through the vast weathered landscapes – made up of sunlight and shadow, rock, scrub, streams and fast flowing rivers.