PDF Altai-Sayan Ecoregion Conservation Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

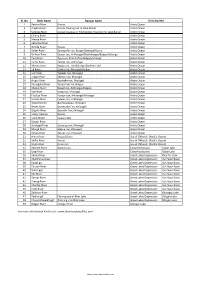

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Birding in the Gobi, Steppe and High Mountains of Mongolia

Birding in the Gobi, Steppe and High Mountains of Mongolia In associaiton with Mongolian Bird Conservation Center Trip date: June 2-16, 2019 Itinerary Day 1, June 2 Ulaanbaatar Ulaanbaatar is the capital of Mongolia, located on the basins of Tuul River valley. It is nestled on the foothills Bogd Khan Uul National Park on its outhern part. Originally a nomadic Buddhist center, it became a permanent city in the 18th century. A Soviet-era influenced architecture co-exists with old monasteries and 21st-century highrises. Enjoy a short city tour followed by a welcome dinner at a fine local restaurant. (Hotel Ulaanbaatar; D) Day 2, June 3 Gobi Gurvan Saikhan Mountain NP In the morning, we will begin driving south to the mighty Gobi Desert (7-8 hours). En eoute, we will stop to have a lunch at a road cafe. In the afternoon, arrive at the ger camp and overnight in gers. (Ger camp; B, L, D) Days 3-4, June 4-5 Gobi Gurvansaikhan Mountain / Flaming Cliffs In the next to days, we will explore the magnificent Gobi Gurvan Saikhan National Park lies on the northern edge of the Gobi desert. We will spend following two days birding in the Mountain. Hike up into the narrow canyon surrounded by steep, giant mountain formation (2600m). Noteworthy species that we may encounter here today include nesting Saker falcon, Chukar, Chinese Beautiful and Common Rosefinches and migrating Thickbilled warbler, Barred warbler, Common whitethroat, Isabelline Wheatear, Brown Shrike, Brown and Alpine Accentors, Blackfaced and Pallas’s Reed Buntings. Our first stop starts with a journey to Yolyn-Am Valley in Zuun Saikhan Mountain Range. -

0001465212.Pdf(1.32

1 2 Geopolitics of the Russo-Korean Gas Pipeline Project and Energy Cooperation in Northeast Asia Printed 0D\ Published 0D\ Published by.RUHD,QVWLWXWHIRU1DWLRQDO8QLILFDWLRQ .,18 Publisher3UHVLGHQW.RUHD,QVWLWXWHIRU1DWLRQDO8QLILFDWLRQ Editor([WHUQDO&RRSHUDWLRQ7HDP'LYLVLRQRI3ODQQLQJDQG&RRUGLQDWLRQ Registration number1R $SULO AddressUR 6X\XGRQJ *DQJEXNJX6HRXO.RUHD Telephone Fax HomepageKWWSZZZNLQXRUNU Design/Print+\XQGDL$UWFRP ISBN &RS\ULJKW.RUHD,QVWLWXWHIRU1DWLRQDO8QLILFDWLRQ $OO.,18SXEOLFDWLRQVDUHDYDLODEOHIRUSXUFKDVHDWDOOPDMRUERRNVWRUHVLQ.RUHD $OVRDYDLODEOHDWWKH*RYHUQPHQW3ULQWLQJ2IILFH6DOHV&HQWHU 6WRUH 2IILFH The Geopolitics of Russo-Korean Gas Pipeline Project Geopolitics of the Russo- Korean Gas Pipeline Project and Energy Cooperation in Northeast Asia 7KHDQDO\VHVFRPPHQWVDQGRWKHURSLQLRQVFRQWDLQHGLQWKLVPRQRJUDSKDUHWKRVH RIWKHDXWKRUV DQGGRQRWQHFHVVDULO\UHSUHVHQWWKHYLHZVRIWKH.RUHD,QVWLWXWHIRU 1DWLRQDO8QLILFDWLRQ Geopolitics of the Russo- Korean Gas Pipeline Project and Energy Cooperation in Northeast Asia 1. Introduction ···················································································· 8 2. The Geopolitics of Competition and Conflict since the halt of the Russo-Korean Pipeline ························································· 16 A. Chinese proposal for Russo-Sino-Korean gas pipeline cooperation ·· 18 B. Likelihood of changes in Russia’s position ······························ 26 C. Expansion of the Japanese factor ············································ 32 D. Internal conflicts in South Korea and the -

Estimation of Pasture Productivity in Mongolian Grasslands: Field Survey and Model Simulation

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240797895 Estimation of pasture productivity in Mongolian grasslands: Field survey and model simulation Article in Journal of Agricultural Meteorology · January 2010 DOI: 10.2480/agrmet.66.1.6 CITATIONS READS 11 336 3 authors: Tserenpurev Bat-Oyun Masato Shinoda Institute of Meteorology, Hydrology and Environment Nagoya University 14 PUBLICATIONS 95 CITATIONS 132 PUBLICATIONS 1,859 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Mitsuru Tsubo Tottori University 116 PUBLICATIONS 2,727 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Migration ecology and conservation of Mongolian wild ungulates View project Sand fluxes and its vertical distribution in the southern Mongolia: A sand storm case study for 2011 View project All content following this page was uploaded by Tserenpurev Bat-Oyun on 06 January 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Full Paper J. Agric. Meteorol. (農業気象) 66 (1): 31-39, 2010 Estimation of pasture productivity in Mongolian grasslands: field survey and model simulation Tserenpurev BAT-OYUN†, Masato SHINODA, and Mitsuru TSUBO (Arid Land Research Center, Tottori University, Hamasaka, Tottori, 680–0001, Japan) Abstract The Mongolian economy depends critically on products of range-fed livestock. Pasture is the major food source for livestock grazing, and its productivity is strongly affected by climatic variability. Direct measurement of pasture productivity is time-consuming and difficult, especially in remote areas of a large country like Mongolia with sparse spatial distribution of pasture monitoring. Therefore, model- ing is a valuable tool to simulate pasture productivity. -

Infrastructure Strategy Review Making Choices in Provision of Infrastructure Services

MONGOLIA Infrastructure Strategy Review Making Choices in Provision of Infrastructure Services S. Rivera East Asia & Pacific The World Bank Government of Mongolia: Working Group Technical Donors Meeting October, 2006. 1 Mongolia: Infrastructure Strategy The Process and Outputs Factors Shaping Infrastructure Strategy Demand Key Choices to discuss this morning 2 Process and Outcome The Process – An interactive process, bringing together international practices: Meeting in Washington, March 2005. Field work in the late 2005. Preparation of about 12 background notes in sector and themes, discussed in Washington on June 2006. Submission of final draft report in November, 2006 Launching of Infrastructure Strategy report in a two day meeting in early 2007. Outcome A live document that can shape and form policy discussions on PIP, National Development Plan, and Regional Development Strategy….it has been difficult for the team to assess choices as well. 3 Factors Shaping the IS • Urban led Size and Growth of Ulaanbaatar and Selected Aimag (Pillar) Centers Size of the Circle=Total Population ('000) Infrastructure 6% 5% 869.9 Investments ) l 4% ua nn 3% a Ulaanbaatar (%, 2% h t Darkhan w Erdenet o 1% r G n 0% o i -10 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 at l -1% Choibalsan Kharkhorin opu Ondorkhaan P -2% Khovd Uliastai -3% Zuunmod -4% Share of Total Urban Population (%) 4 Factors Shaping the IS: Connectivity, with the World and in Mongolia Khankh Khandgait Ulaanbaishint Ereentsav Khatgal Altanbulag ULAANGOM Nogoonnuur UVS KHUVSGUL Tsagaannuur ÒýñTes -

The Mineral Industry of Russia in 2010

2010 Minerals Yearbook RUSSIA U.S. Department of the Interior October 2012 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF RUSSIA By Elena Safirova Russia was one of the world’s leading mineral-producing Of Russia’s total spending on geologic prospecting, 80.8% countries. In 2010, Russia was ranked among the world’s went into exploration for oil and gas, 9% into exploration for leading producers or was a leading regional producer of such precious metals, and 1.9% into exploration for diamond. In mineral commodities as aluminum, arsenic, asbestos, bauxite, terms of the sources of financing, 70.4% of exploration spending boron, cadmium, cement, coal, cobalt, copper, diamond, was financed by the mineral industry, 16.7% came from fluorspar, gold, iron ore, lime, magnesium compounds and domestic and foreign investors, and 8.2% was contributed from metals, mica (flake, scrap, and sheet), natural gas, nickel, the Federal budget (Federal’naya Sluzhba Gosudarstvennoy nitrogen, oil shale, palladium, peat, petroleum, phosphate, pig Statistiki, 2011b). iron, platinum, potash, rhenium, silicon, steel, sulfur, titanium sponge, tungsten, and vanadium (Angulo, 2012; Apodaca; Government Policies and Programs 2012a–c; Bray, 2012a, b; Brooks, 2012; Corathers, 2012; Edelstein, 2012; Fenton, 2012; Gambogi, 2012; George, In 2009, the Ministry of Industry and Trade of Russia 2012; Jasinski, 2012a, b; Jorgenson, 2012; Kramer, 2012a, b; announced a new program “Strategy for Development of the Kuck, 2012; Loferski, 2012; Miller, 2012a, b; Olson, 2012; Metallurgical Industry for the Period through 2020.” The Polyak, 2012a, b; Shedd, 2012a, b; Tolcin, 2012; van Oss, 2012; new strategy emphasizes metallurgy as one of the sectors of Virta, 2012; Willett, 2012). -

INFLUENCE of SOIL-ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS on VEGETATION ZONATION in a WESTERN MONGOLIAN LAKE SHORE- SEMI-DESERT ECOTONE with 6 Figures, 4 Tables and 4 Photos

72 Erdkunde Band 61/2007 INFLUENCE OF SOIL-ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS ON VEGETATION ZONATION IN A WESTERN MONGOLIAN LAKE SHORE- SEMI-DESERT ECOTONE With 6 figures, 4 tables and 4 photos ANDREA STRAUSS and UDO SCHICKHOFF Keywords: Vegetation geography, soil geography, environmental change, Central Asia, semidesert environments Keywords: Vegetationsgeographie, Bodengeographie, Umweltforschung, Zentralasien, aride Räume Zusammenfassung: Der Einfluss bodenökologischer Bedingungen auf die Vegetationszonierung in einem Seeufer-Halb- wüsten-Ökoton der westlichen Mongolei Das Becken der Großen Seen in der Westmongolei ist geprägt von ausgedehnten Wüsten-, Halbwüsten- und Steppen- arealen sowie von Seen und umgebenden einzigartigen Feuchtgebieten. Diese Feuchtgebiete sind bedeutende Elemente der Landschaftsökosysteme semi-arider und arider Räume. Andererseits ist die Kenntnis selbst grundlegender Ökosystemkompo- nenten wie Vegetation und Böden noch sehr lückenhaft. Das Ziel der vorliegenden landschaftsökologischen Studie entlang eines Seeufer-Halbwüsten-Ökotons war es, das klein- räumige Muster von Standortfaktoren entlang eines ausgeprägten Umweltgradienten sowie den Einfluss dieses Musters auf die Vegetationszonierung zu analysieren. Um die Veränderungen in dem Übergangsbereich zwischen aquatischen und terres- trischen Lebensräumen adäquat zu erfassen, wurden die Daten mit einem Transekt-Ansatz aufgenommen. Pflanzengesell- schaften wurden nach der Braun-Blanquet-Methode klassifiziert. Die Vegetations- und Bodendaten wurden einer Detrended Correspondence -

Second Report Submitted by the Russian Federation Pursuant to The

ACFC/SR/II(2005)003 SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 2 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES (Received on 26 April 2005) MINISTRY OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION REPORT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PROVISIONS OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES Report of the Russian Federation on the progress of the second cycle of monitoring in accordance with Article 25 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities MOSCOW, 2005 2 Table of contents PREAMBLE ..............................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction........................................................................................................................4 2. The legislation of the Russian Federation for the protection of national minorities rights5 3. Major lines of implementation of the law of the Russian Federation and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities .............................................................15 3.1. National territorial subdivisions...................................................................................15 3.2 Public associations – national cultural autonomies and national public organizations17 3.3 National minorities in the system of federal government............................................18 3.4 Development of Ethnic Communities’ National -

Tuul River Mongolia

HEALTHY RIVERS FOR ALL Tuul River Basin Report Card • 1 TUUL RIVER MONGOLIA BASIN HEALTH 2019 REPORT CARD Tuul River Basin Report Card • 2 TUUL RIVER BASIN: OVERVIEW The Tuul River headwaters begin in the Lower As of 2018, 1.45 million people were living within Khentii mountains of the Khan Khentii mountain the Tuul River basin, representing 46% of Mongolia’s range (48030’58.9” N, 108014’08.3” E). The river population, and more than 60% of the country’s flows southwest through the capital of Mongolia, GDP. Due to high levels of human migration into Ulaanbaatar, after which it eventually joins the the basin, land use change within the floodplains, Orkhon River in Orkhontuul soum where the Tuul lack of wastewater treatment within settled areas, River Basin ends (48056’55.1” N, 104047’53.2” E). The and gold mining in Zaamar soum of Tuv aimag and Orkhon River then joins the Selenge River to feed Burenkhangai soum of Bulgan aimag, the Tuul River Lake Baikal in the Russian Federation. The catchment has emerged as the most polluted river in Mongolia. area is approximately 50,000 km2, and the river itself These stressors, combined with a growing water is about 720 km long. Ulaanbaatar is approximately demand and changes in precipitation due to global 470 km upstream from where the Tuul River meets warming, have led to a scarcity of water and an the Orkhon River. interruption of river flow during the spring. The Tuul River basin includes a variety of landscapes Although much research has been conducted on the including mountain taiga and forest steppe in water quality and quantity of the Tuul River, there is the upper catchment, and predominantly steppe no uniform or consistent assessment on the state downstream of Ulaanbaatar City. -

Транспортная Стратегия ЦАРЭС 2030 (CAREC Transport Strategy

Транспортная стратегия ЦАРЭС 2030 Новая Транспортная стратегия ЦАРЭС 2030 основывается на достигнутом прогрессе и уроках, извлеченных из Стратегии ЦАРЭС по транспорту и содействию торговле до 2020 года. Ее ключевые связи с общей программой ЦАРЭС 2030 находятся в областях улучшения связанности и устойчивости. Данная стратегия заключается в упрощении, нашедшем свое отражение, прежде всего, в отделении содействия торговле от транспорта. Она в равной степени уделяет внимание повышению устойчивости и качества сетей, наряду с непрерывным строительством и капитальным ремонтом транспортных коридоров. Нынешняя Транспортная стратегия будет реализовываться в сочетании с недавней Интегрированной программой по торговле ЦАРЭС до 2030 года. О Программе Центральноазиатского регионального экономического сотрудничества Программа Центральноазиатского регионального экономического сотрудничества (ЦАРЭС) – это партнерство 11 стран-членов, а также партнеров по развитию, работающих совместно для продвижения развития посредством сотрудничества, приводящего к ускоренному экономическому росту и сокращению бедности. Оно руководствуется общим видением “Хорошие соседи, хорошие партнеры и хорошие перспективы”. В число стран ЦАРЭС входят: Афганистан, Азербайджан, Китайская Народная Республика, Грузия, Казахстан, Кыргызская Республика, Монголия, Пакистан, Таджикистан, Туркменистан и Узбекистан. АБР выполняет функции Секретариата ЦАРЭС Об Азиатском банке развития АБР стремится к достижению процветания, всеохватности, стабильности и устойчивости в Азии и Тихоокеанском регионе, -

MONGOLIA: Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized

MONGOLIA: Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Acknowledgements This Mongolia Strategic Country Diagnostic was led by Samuel Freije-Rodríguez (lead economist, GPV02) and Tuyen Nguyen (resident representative, IFC Mongolia). The following World Bank Group experts participated in different stages of the production of this diagnostics by providing data, analytical briefs, revisions to several versions of the document, as well as participating in several internal and external seminars: Rabia Ali (senior economist, GED02), Anar Aliyev (corporate governance officer, CESEA), Indra Baatarkhuu (communications associate, EAPEC), Erdene Badarch (operations officer, GSU02), Julie M. Bayking (investment officer, CASPE), Davaadalai Batsuuri (economist, GMTP1), Batmunkh Batbold (senior financial sector specialist, GFCP1), Eileen Burke (senior water resources management specialist, GWA02), Burmaa Chadraaval (investment officer, CM4P4), Yang Chen (urban transport specialist, GTD10), Tungalag Chuluun (senior social protection specialist, GSP02), Badamchimeg Dondog (public sector specialist, GGOEA), Jigjidmaa Dugeree (senior private sector specialist, GMTIP), Bolormaa Enkhbat (WBG analyst, GCCSO), Nicolaus von der Goltz (senior country officer, EACCF), Peter Johansen (senior energy specialist, GEE09), Julian Latimer (senior economist, GMTP1), Ulle Lohmus (senior financial sector specialist, GFCPN), Sitaramachandra Machiraju (senior agribusiness specialist, -

Industrial Single-Industry Areas, Socio-Economic Development Based on Cluster Approach

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 128 International Scientific Conference "Far East Con" (ISCFEC 2020) Industrial Single-Industry Areas, Socio-Economic Development Based on Cluster Approach A N Bikineeva1, O N Nedzelsky2, E N Bulakina2 1GAOU VO"Khakas state University", Russian Federation, Abakan 2Federal STATE Autonomous educational institution, "Siberian Federal University" Russian Federation, Krasnoyarsk E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The article presents research, socio-economic development of coal-mining areas of the Republic of Khakassia. It is proved that the increasing economic changes, overcoming the crisis phenomena of increasing variability of organizational and technological systems, determine the need to develop new methodological approaches to the assessment of the most important areas of specialization of the industrial region - the coal mining industry. As a priority direction in the process of industry diversification, the authors consider the cluster approach that contributes to the development of industrial areas. Newly created business entities can become a source of new jobs, tax revenues to the budget of single-profile territories. Currently, the project of development of polycentric Abakan-Montenegrin agglomeration is promising. The presence and nature of interaction is manifested in the intensity of labor and economic migration (labor and capital) between settlements. Particular attention is paid to the control of the implementation of innovation-oriented management strategy,