Identifying Riparian Areas of Free Flowing Rivers for Legal Protection: Model Region Mongolia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

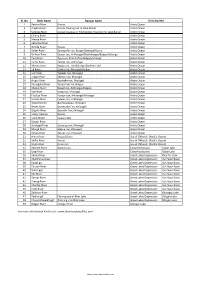

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

INFLUENCE of SOIL-ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS on VEGETATION ZONATION in a WESTERN MONGOLIAN LAKE SHORE- SEMI-DESERT ECOTONE with 6 Figures, 4 Tables and 4 Photos

72 Erdkunde Band 61/2007 INFLUENCE OF SOIL-ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS ON VEGETATION ZONATION IN A WESTERN MONGOLIAN LAKE SHORE- SEMI-DESERT ECOTONE With 6 figures, 4 tables and 4 photos ANDREA STRAUSS and UDO SCHICKHOFF Keywords: Vegetation geography, soil geography, environmental change, Central Asia, semidesert environments Keywords: Vegetationsgeographie, Bodengeographie, Umweltforschung, Zentralasien, aride Räume Zusammenfassung: Der Einfluss bodenökologischer Bedingungen auf die Vegetationszonierung in einem Seeufer-Halb- wüsten-Ökoton der westlichen Mongolei Das Becken der Großen Seen in der Westmongolei ist geprägt von ausgedehnten Wüsten-, Halbwüsten- und Steppen- arealen sowie von Seen und umgebenden einzigartigen Feuchtgebieten. Diese Feuchtgebiete sind bedeutende Elemente der Landschaftsökosysteme semi-arider und arider Räume. Andererseits ist die Kenntnis selbst grundlegender Ökosystemkompo- nenten wie Vegetation und Böden noch sehr lückenhaft. Das Ziel der vorliegenden landschaftsökologischen Studie entlang eines Seeufer-Halbwüsten-Ökotons war es, das klein- räumige Muster von Standortfaktoren entlang eines ausgeprägten Umweltgradienten sowie den Einfluss dieses Musters auf die Vegetationszonierung zu analysieren. Um die Veränderungen in dem Übergangsbereich zwischen aquatischen und terres- trischen Lebensräumen adäquat zu erfassen, wurden die Daten mit einem Transekt-Ansatz aufgenommen. Pflanzengesell- schaften wurden nach der Braun-Blanquet-Methode klassifiziert. Die Vegetations- und Bodendaten wurden einer Detrended Correspondence -

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River Valley Results of the 2005 Joint American-Mongolian Expedition to Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu, Ogii nuur, Arkhangai aimag, Mongolia David E. Purcell and Kimberly C. Spurr Flagstaff, Arizona (USA) During the summer of 2005 an archaeological investigations, and What is known points to this area archaeological expedition jointly their results, are the focus of this as one of the most important mounted by the Silkroad Foun- article, which is a preliminary and cultural regions in the world, a fact dation of Saratoga, California, incomplete record of the project recently recognized by the U.S.A. and the Mongolian National findings. Not all of the project data UNESCO through designation of University, Ulaanbataar, investi- — including osteological analysis of the Orkhon Valley as a World gated two sites near the the burials, descriptions or maps Heritage Site in 2004 (UNESCO confluence of the Tamir River with of the graves, or analyses of the 2006). Archaeological remains the Orkhon River in the Arkhangai artifacts — is available as of this indicate the region has been aimag of central Mongolia (Fig. 1). writing. Consequently, the greater occupied since the Paleolithic (circa The expedition was permitted emphasis falls on one of the two 750,000 years before present), (Registration Number 8, issued sites. It is hoped that through the with Neolithic sites found in great June 23, 2005) by the Ministry of Silkroad Foundation, the many numbers. As early as the Neolithic Education, Culture and Science of different collections from this period a pattern developed in Mongolia. The project had multiple project can be reunited in a which groups moved southward goals: archaeological investiga- scholarly publication. -

Ìîíãîë Íóòàã Äàõü Ò¯¯Õ, Ñî¨Ëûí ¯Ë Õªäëªõ Äóðñãàë

ÀÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÀÉÌÃÈÉÍ ÍÓÒÀà ÄÀÕÜ Ò¯¯Õ, ÑΨËÛÍ ¯Ë ÕªÄËªÕ ÄÓÐÑÃÀË ISBN 978-99962-67-33-8 ÑΨËÛÍ ªÂÈÉÍ ÒªÂ ÌÎÍÃÎË ÍÓÒÀà ÄÀÕÜ Ò¯¯Õ, ÑΨËÛÍ ¯Ë ÕªÄËªÕ ÄÓÐÑÃÀË HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL IMMOVABLE MONUMENTS IN MONGOLIA X ÄÝÂÒÝÐ ÀÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÀÉÌÀà 1 ÀÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÀÉÌÃÈÉÍ ÍÓÒÀà ÄÀÕÜ Ò¯¯Õ, ÑΨËÛÍ ¯Ë ÕªÄËªÕ ÄÓÐÑÃÀË ÌÎíãÎë íóòàã äàõü ò¯¯õ, ñΨëûí ¯ë õªäëªõ äóðñãàë X äýâòýð ÀðõÀíãÀé ÀéìÀã 1 DDC 900 Ý-66 Зохиогч: Г.Энхбат Г.аНХСАНАА б.ДаваацЭрЭн Гэрэл зургийг: б.ДаваацЭрЭн П.Чинбат Гар зургийг: а.мӨнГӨНЦООЖ т.эРДЭнЭцОГт Г.аНХСАНАА Дизайнер: б.аЛТАНСҮх Орчуулагч: ц.цОЛмОн Жолооч: б.ЭрДЭнЭЧИМЭГ Зохиогчийн эрх хамгаалагдсан. © 2013, Copyrigth © 2013 by the Center of Cultural Соёлын өвийн төв, Улаанбаатар, монгол улс Heritage, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia Энэхүү цомгийг Соёлын өвийн төвийн зөвшөөрөлгүйгээр бүтнээр нь буюу хэсэгчлэн хувилан олшруулахыг хориглоно. монгол улс Улаанбаатар хот - 211238 Сүхбаатар дүүрэг Сүхбаатарын талбай 3 Соёлын төв өргөө б хэсэг Соёлын өвийн төв Шуудангийн хайрцаг 223 веб сайт: www.monheritage.mn и-мэйл: [email protected] Утас: 976-70110877 ISBN 978-99962-67-33-8 Соёл, Спорт, аялал Соёлын өвийн төв архангай аймгийн жуулчлалын яам музей 2 ÃÀÐ×Èà Өмнөх үг 4 Удиртгал 5 архангай аймгийн нутаг дахь түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалын тухай 18 архангай аймгийн нутаг дахь түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалын байршил 36 батцэнгэл сум 37 булган сум 46 Жаргалант 50 их тамир сум 55 Өгийнуур сум 61 Өлзийт сум 64 Өндөр-Улаан сум 68 тариат сум 73 төвширүүлэх сум 76 хангай сум 78 хайрхан сум 81 хашаат сум 85 хотонт сум 88 цахир сум 91 цэнхэр сум 94 цэцэрлэг сум 97 Чулуут 100 Эрдэнэмандал 103 Эрдэнэбулган 111 архангай аймгийн нутаг дахь түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалын жагсаалт 114 товчилсон үгийн тайлал 116 ашигласан ном бүтээлийн жагсаалт 117 ªÌÍªÕ ¯Ã СаЖЯ-ны харьяа Соёлын өвийн төв монгол нутагт оршин буй түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалыг анхан Сшатны байдлаар бүртгэн баримтжуулах, тоолох, хадгалалт хамгаалалт, ашиглалтын байдалд судалгаа хийх ажлыг 2008-2015 онд гүйцэтгэхээр төлөвлөн хэрэгжүүлж эхлээд байгаа билээ. -

Impacts of Late Quaternary Environmental Change on the Long-Tailed Ground Squirrel (Urocitellus Undulatus) in Mongolia

ZOOLOGICAL RESEARCH Impacts of late Quaternary environmental change on the long-tailed ground squirrel (Urocitellus undulatus) in Mongolia Bryan S. McLean1,*, Batsaikhan Nyamsuren2, Andrey Tchabovsky3, Joseph A. Cook4 1 University of Florida, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA 2 Department of Biology, School of Arts and Sciences, National University of Mongolia, Ulaan Baatar 11000, Mongolia 3 Laboratory of Population Ecology, A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Moscow 119071, Russia 4 University of New Mexico, Department of Biology and Museum of Southwestern Biology, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA ABSTRACT of range shifts into these lowland areas in response to Pleistocene glaciation and environmental change, Impacts of Quaternary environmental changes on followed by upslope movements and mitochondrial mammal faunas of central Asia remain poorly lineage sorting with Holocene aridification. Our study understood due to a lack of comprehensive illuminates possible historical mechanisms responsible phylogeographic sampling for most species. To for U. undulatus genetic structure and contributes to help address this knowledge gap, we conducted a framework for ongoing exploration of mammalian the most extensive molecular analysis to date of response to past and present climate change in central the long-tailed ground squirrel (Urocitellus undulatus Asia. Pallas 1778) in Mongolia, a country that comprises Keywords: Central Asia; Gobi Desert; Great Lakes the southern core of this species’ range. Drawing on Depression; Mongolia; Phylogeography material from recent collaborative field expeditions, we genotyped 128 individuals at two mitochondrial INTRODUCTION genes (cytochrome b and cytochrome oxidase I; Urocitellus undulatus Pallas 1778 is a charismatic, 1 797 bp total). Phylogenetic inference supports the medium-bodied ground-dwelling sciurid distributed across existence of two deeply divergent infraspecific lineages central Asia, including portions of Siberia, Mongolia, (corresponding to subspecies U. -

Thesis Local Understanding of Hydro-Climate Changes

THESIS LOCAL UNDERSTANDING OF HYDRO-CLIMATE CHANGES IN MONGOLIA Submitted by Tumenjargal Sukh Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2012 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Steven Fassnacht Melinda Laituri Maria Fernandez-Gimenez Greg Butters Copyright by Tumenjargal Sukh 2012 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT LOCAL UNDERSTANDING OF HYDRO-CLIMATE CHANGES IN MONGOLIA Air temperatures have increased more in semi-arid regions than in many other parts of the world. Mongolia has an arid/semi-arid climate where much of the population is dependent upon the limited water resources, especially herders. This paper combines herder observations of changes in water availability in streams and from groundwater with an analysis of climatic and hydrologic change from station data to illustrate the degree of change of Mongolian water resources. We find that herders’ local knowledge of hydro-climatic changes is similar to the station based analysis. However, station data are spatially limited, so local knowledge can provide finer scale information on climate and hydrology. We focus on two regions in central Mongolia: the Jinst soum in Bayankhongor aimag in the desert steppe region and the Ikh-Tamir soum in Arkhangai aimag in the mountain steppe. As the temperatures have increased significantly (more in Ikh-Tamir than Jinst), precipitation amounts have decreased in Ikh-Tamir which corresponds to a decrease in streamflow, in particular, the average annual streamflow and the annual peak discharge. At Erdenemandal (Ikh-Tamir) the number of days with precipitation has decreased while at Horiult (Jinst) it has increased. -

Palaeoclimate, Glacier and Treeline Reconstruction Based On

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2018 Palaeoclimate, glacier and treeline reconstruction based on geomorphic evidences in the Mongun-Taiga massif (south-eastern Russian Altai) during the Late Pleistocene and Holocene Ganyushkin, Dmitry ; Chistyakov, Kirill ; Volkov, Ilya ; Bantcev, Dmitry ; Kunaeva, Elena ; Brandová, Dagmar ; Raab, Gerald ; Christl, Marcus ; Egli, Markus Abstract: Little is known about the extent of glaciers and dynamics of the landscape in south-eastern Russian Altai. The effects of climate-induced fluctuations of the glaciers and the upper treeline of the Mongun-Taiga mountain massif were, therefore, reconstructed on the basis of in-situ, multiannual observations, geomorphic mapping, radiocarbon and surface exposure dating, relative dating (such as Schmidthammer and weathering rind) techniques and palaeoclimate-modelling. During the maximal advance of the glaciers, their area was 26-times larger than now and the equilibrium line of altitude (ELA) was about 800m lower. Assuming that the maximum glacier extent took place during MIS 4, then the average summer temperatures were 2.7℃ cooler than today and the amount of precipitation 2.1 times higher. Buried wood trunks by a glacier gave ages between 60 and 28 cal ka BP and were found 600-700m higher than the present upper treeline. This evidences a distinctly elevated treeline during MIS 3a and c. With a correction for tectonics we reconstructed the summer warming to have been between 2.1 and 3.0℃. During MIS 3c, the glaciated area was reduced to less than 0.5 km² with an increase of the ELA of 310-470m higher than today. -

Briefing Note on Mongolia Briefing Note on Mongolia

Briefing Note on Mongolia BRIEFING NOTE ON MONGOLIA INTRODUCTION Mongolia is of global significance from a biodiversity perspective because of its location at the convergence of the Great Siberian taiga and the Cen- tral Asian steppe and deserts. The region is home to unique transitional ecosystems and assemblages of species. Mongolia's biological wealth is closely linked to its distinct cultural and human landscape. Because urban and industrial development is concentrated in less than 1% of the country’s area (Anand, 2011), Mongolia's ecosystems are still relatively intact. However, because of the country's location and extreme climate, these ecosystems are sensitive to human interference. DEVELOPMENT The 1995 Environmental Protection Law is the bedrock of the country’s legal framework for the environment. In addition, major environmen- POLICY SETTING tal policies have been defined in the Principles of National Security, the Universal Sustainable Development Policy, the Principles of Sustain- able Development of Mongolia in the 21st Century, Government Policy on Ecology and the Millennium Development Goals of Mongolia. These overarching policy frameworks establish mechanisms for: • Limiting environmental pollution and halting ecological degrada- tion; • Encouraging more responsible use of land and mineral resources; • Protecting and ensuring sustainable use of water resources; • The sustainable use and protection of forest reserves, reforesta- tion and maintaining the ecological balance; and • Limiting biodiversity loss and creating conditions -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- - 1. Name and contact details of the compiler of this form *: Full name: Mr. B. Buyantsog and Dr. Gombobaatar EAAF SITE CODE FOR OFFICE USE ONLY: Sundev Institution/agency: Khan Huhiin Nuruu Protected Area and Administration Mongolian Ornithological Society. -

PDF Altai-Sayan Ecoregion Conservation Strategy

Altai-Sayan Ecoregion Conservation Strategy FINAL DRAFT VERSION, approved by the Altai-Sayan Steering Committee on 29 June 2012, considering the amendments and comments made during the teleconference of 29 June 2012, as described in the meetings notes of that meeting COLOFON Altai-Sayan Ecoregion Conservation Strategy Full Version © WWF, July 2012 Cover photo: Desert steppe Tuva region (Hartmut Jungius/ WWF-Canon) ii Table of Contents Contribution to WWF Global Conservation Programme .................................................................................................................. 1 Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 1- Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 2- Outlining the Altai-Sayan Ecoregion ............................................................................................................................................. 9 2.1 Background ................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Coleoptera: Dytiscidae) 43-53 ©Wiener Coleopterologenverein (WCV), Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Koleopterologische Rundschau Jahr/Year: 2008 Band/Volume: 78_2008 Autor(en)/Author(s): Shaverdo Helena Vladimirovna, Short Andrew Edward Z., Davaadorj E.Enkhnasan Artikel/Article: Diving Beetles of Mongolia (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae) 43-53 ©Wiener Coleopterologenverein (WCV), download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Koleopterologische Rundschau 78 43–53 Wien, Juli 2008 Diving Beetles of Mongolia (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae) H.V. SHAVERDO, A.E.Z. SHORT & E. DAVAADORJ Abstract Sixty-four species of the water beetle family Dytiscidae were collected from 84 localities in the north- central part of Mongolia, in the basin of the Selenge River, during 2003–2006. Twenty species and one subspecies of Dytiscidae are recorded from Mongolia for the first time. According to the present study and literature data, 87 species of Dytiscidae are currently known from Mongolia. Key words: Coleoptera, Dytiscidae, faunistics, Mongolia. Introduction The dytiscid fauna of Mongolia is relatively well known due to the works of BELLSTEDT (1985), BRANCUCCI (1982), BRINCK (1943), GUÉORGUIEV (1965, 1968, 1969, 1972), and more recent Dr. Hildegard studies (FERY 2003, SHAVERDO 2004, SHAVERDO & FERY 2001). WINKLER Nonetheless, new faunistic data and new species of Dytiscidae were obtained recently through the “Selenge River Basin Expeditions, 2003–2006” (FERY & PETROV 2006, SHAVERDO & FERY Fachgeschäft und 2006). Buchhandlung The aim of this paper is to report the faunistic results of the Dytiscidae collected during the “Selenge River Basin Expeditions, 2003–2006”, and to present a checklist of the Mongolian für Entomologie dytiscids known so far. A similar checklist for the Hydrophilidae has been published by SHORT & KANDA (2006). -

Glaciers, Permafrost and Lake Levels at the Tsengel Khairkhan Massif, Mongolian Altai, During the Late Pleistocene and Holocene

Article Glaciers, Permafrost and Lake Levels at the Tsengel Khairkhan Massif, Mongolian Altai, During the Late Pleistocene and Holocene Michael Walther 1,*, Avirmed Dashtseren 1, Ulrich Kamp 2, Khurelbaatar Temujin 1, Franz Meixner 3, Caleb G. Pan 4 and Yadamsuren Gansukh 1 1 Institute of Geography and Geoecology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, P.O.B. 361, Ulaanbaatar 14192, Mongolia; [email protected] (A.D.); [email protected] (K.T.); [email protected] (Y.G.) 2 Department of Geography, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Atmospheric Chemistry, Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, 55128 Mainz, Germany; [email protected] 4 Systems Ecology Program, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +976-9908-7055 Received: 31 May 2017; Accepted: 11 August 2017; Published: 16 August 2017 Abstract: Understanding paleo—and recent environmental changes and the dynamics of individual drivers of water availability is essential for water resources management in the Mongolian Altai. Here, we follow a holistic approach to uncover changes in glaciers, permafrost, lake levels and climate at the Tsengel Khairkhan massif. Our general approach to describe glacier and lake level changes is to combine traditional geomorphological field mapping with bathymetric measurements, satellite imagery interpretation, and GIS analyses. We also analysed climate data from two nearby stations, and measured permafrost temperature conditions at five boreholes located at different elevations. We identified four glacial moraine systems (M4-M1) and attribute them to the period from the penultimate glaciation (MIS 4/5) until the Little Ice Age (MIS 1).