Nomads and Settlement: New Perspectives in the Archaeology of Mongolia, by Daniel C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Currents 31 | 1 Introduction

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review Title Introduction to "Buddhist Art of Mongolia: Cross-Cultural Connections, Discoveries, and Interpretations" Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5kj9c57m Journal Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 1(31) ISSN 2158-9674 Author Tsultemin, Uranchimeg Publication Date 2019-06-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction to “Buddhist Art of Mongolia: Cross-Cultural Connections, Discoveries, and Interpretations” Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2019. “Introduction to ‘Buddhist Art of Mongolia: Cross-Cultural Connections, Discoveries, and Interpretations.’” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (e-journal) 31: 1– 6. https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-31/introduction. A comparative and analytical discussion of Mongolian Buddhist art is a long overdue project. In the 1970s and 1980s, Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem’s lavishly illustrated publications broke ground for the study of Mongolian Buddhist art.1 His five-volume work was organized by genre (painting, sculpture, architecture, decorative arts) and included a monograph on a single artist, Zanabazar (Tsultem 1982a, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989). Tsultem’s books introduced readers to the major Buddhist art centers and sites, artists and their works, techniques, media, and styles. He developed and wrote extensively about his concepts of “schools”—including the school of Zanabazar and the school of Ikh Khüree—inspired by Mongolian ger- (yurt-) based education, the artists’ teacher- disciple or preceptor-apprentice relationships, and monastic workshops for rituals and production of art. The very concept of “schools” and its underpinning methodology itself derives from the Medieval European practice of workshops and, for example, the model of scuola (school) evidenced in Italy. -

List of Rivers of Mongolia

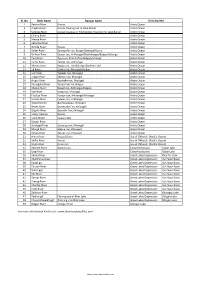

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Journal Biology 2004 3

Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences 2004 Vol. 2(1): 39-42 Hydrochemical Characteristics of Selenge River and its Tributaries on the Territory of Mongolia Bazarova J.G. 1, Dorzhieva S.G.1, Bazarov B.G. 1, Barkhutova D.D.2, Dagurova O.P.2, Namsaraev B.B. 2 and Zhargalova S.O.2 1Baikal Institute of Nature Management of SB RAS, Ulan-Ude, 2Institute of General and Experimental Biology of SB RAS, Ulan-Ude, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Hydrochemical research of the Selenge and its main tributary the Orkhon river on the territory of Mongolia has been conducted. Concentrations of the main water ions were measured. Distribution of - + heavy metals was determined. Dynamics of biogenic elements (NO3 , NH4 , phosphates) and degree of phenol pollution was determined. Key words: Baikal, biogenic, heavy metals, ions, phenol, Selenge River Introduction river is polluted along its entire length. To assess the current ecological condition in the Mongolian During the last 30-40 years Lake Baikal has part of the Selenge river basin, it is necessary to been influenced by various anthropogenic factors. implement hydrobiological and hydrochemical Industrial and household waste water have changed monitoring. It requires information not only of the chemical composition of Baikal with a chemical composition, but of biogenic components deterioration in water quality in the basin territory. in the processes of accumulation and According to sustainable development policy, transformation in water, bottom sediments and river protection of Baikal region is considered -

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River Valley Results of the 2005 Joint American-Mongolian Expedition to Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu, Ogii nuur, Arkhangai aimag, Mongolia David E. Purcell and Kimberly C. Spurr Flagstaff, Arizona (USA) During the summer of 2005 an archaeological investigations, and What is known points to this area archaeological expedition jointly their results, are the focus of this as one of the most important mounted by the Silkroad Foun- article, which is a preliminary and cultural regions in the world, a fact dation of Saratoga, California, incomplete record of the project recently recognized by the U.S.A. and the Mongolian National findings. Not all of the project data UNESCO through designation of University, Ulaanbataar, investi- — including osteological analysis of the Orkhon Valley as a World gated two sites near the the burials, descriptions or maps Heritage Site in 2004 (UNESCO confluence of the Tamir River with of the graves, or analyses of the 2006). Archaeological remains the Orkhon River in the Arkhangai artifacts — is available as of this indicate the region has been aimag of central Mongolia (Fig. 1). writing. Consequently, the greater occupied since the Paleolithic (circa The expedition was permitted emphasis falls on one of the two 750,000 years before present), (Registration Number 8, issued sites. It is hoped that through the with Neolithic sites found in great June 23, 2005) by the Ministry of Silkroad Foundation, the many numbers. As early as the Neolithic Education, Culture and Science of different collections from this period a pattern developed in Mongolia. The project had multiple project can be reunited in a which groups moved southward goals: archaeological investiga- scholarly publication. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Art, Ritual, and Representation: an Exploration of the Roles of Tsam Dance in Contemporary Mongolian Culture Mikaela Mroczynski SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2008 Art, Ritual, and Representation: An Exploration of the Roles of Tsam Dance in Contemporary Mongolian Culture Mikaela Mroczynski SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Dance Commons, and the History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons Recommended Citation Mroczynski, Mikaela, "Art, Ritual, and Representation: An Exploration of the Roles of Tsam Dance in Contemporary Mongolian Culture" (2008). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 57. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/57 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Art, Ritual, and Representation: An Exploration of the Roles of Tsam Dance in Contemporary Mongolian Culture Mikaela Mroczynski S. Ulziijargal World Learning SIT Study Abroad Mongolia Spring, 2008 2 Mroczynski Acknowledgements: I am amazed by the opportunities I have been given and the help provided to me along the way: Thank you to my friends and family back home, for believing I could make it here and supporting me at every step. Thank you to the entire staff at SIT. You have introduced me to Mongolia, a country I have grown to love with all my heart, and I am infinitely grateful. Thank you to my wonderful advisor Uranchimeg, for your inspiration and support. -

Ìîíãîë Íóòàã Äàõü Ò¯¯Õ, Ñî¨Ëûí ¯Ë Õªäëªõ Äóðñãàë

ÀÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÀÉÌÃÈÉÍ ÍÓÒÀà ÄÀÕÜ Ò¯¯Õ, ÑΨËÛÍ ¯Ë ÕªÄËªÕ ÄÓÐÑÃÀË ISBN 978-99962-67-33-8 ÑΨËÛÍ ªÂÈÉÍ ÒªÂ ÌÎÍÃÎË ÍÓÒÀà ÄÀÕÜ Ò¯¯Õ, ÑΨËÛÍ ¯Ë ÕªÄËªÕ ÄÓÐÑÃÀË HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL IMMOVABLE MONUMENTS IN MONGOLIA X ÄÝÂÒÝÐ ÀÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÀÉÌÀà 1 ÀÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÀÉÌÃÈÉÍ ÍÓÒÀà ÄÀÕÜ Ò¯¯Õ, ÑΨËÛÍ ¯Ë ÕªÄËªÕ ÄÓÐÑÃÀË ÌÎíãÎë íóòàã äàõü ò¯¯õ, ñΨëûí ¯ë õªäëªõ äóðñãàë X äýâòýð ÀðõÀíãÀé ÀéìÀã 1 DDC 900 Ý-66 Зохиогч: Г.Энхбат Г.аНХСАНАА б.ДаваацЭрЭн Гэрэл зургийг: б.ДаваацЭрЭн П.Чинбат Гар зургийг: а.мӨнГӨНЦООЖ т.эРДЭнЭцОГт Г.аНХСАНАА Дизайнер: б.аЛТАНСҮх Орчуулагч: ц.цОЛмОн Жолооч: б.ЭрДЭнЭЧИМЭГ Зохиогчийн эрх хамгаалагдсан. © 2013, Copyrigth © 2013 by the Center of Cultural Соёлын өвийн төв, Улаанбаатар, монгол улс Heritage, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia Энэхүү цомгийг Соёлын өвийн төвийн зөвшөөрөлгүйгээр бүтнээр нь буюу хэсэгчлэн хувилан олшруулахыг хориглоно. монгол улс Улаанбаатар хот - 211238 Сүхбаатар дүүрэг Сүхбаатарын талбай 3 Соёлын төв өргөө б хэсэг Соёлын өвийн төв Шуудангийн хайрцаг 223 веб сайт: www.monheritage.mn и-мэйл: [email protected] Утас: 976-70110877 ISBN 978-99962-67-33-8 Соёл, Спорт, аялал Соёлын өвийн төв архангай аймгийн жуулчлалын яам музей 2 ÃÀÐ×Èà Өмнөх үг 4 Удиртгал 5 архангай аймгийн нутаг дахь түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалын тухай 18 архангай аймгийн нутаг дахь түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалын байршил 36 батцэнгэл сум 37 булган сум 46 Жаргалант 50 их тамир сум 55 Өгийнуур сум 61 Өлзийт сум 64 Өндөр-Улаан сум 68 тариат сум 73 төвширүүлэх сум 76 хангай сум 78 хайрхан сум 81 хашаат сум 85 хотонт сум 88 цахир сум 91 цэнхэр сум 94 цэцэрлэг сум 97 Чулуут 100 Эрдэнэмандал 103 Эрдэнэбулган 111 архангай аймгийн нутаг дахь түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалын жагсаалт 114 товчилсон үгийн тайлал 116 ашигласан ном бүтээлийн жагсаалт 117 ªÌÍªÕ ¯Ã СаЖЯ-ны харьяа Соёлын өвийн төв монгол нутагт оршин буй түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалыг анхан Сшатны байдлаар бүртгэн баримтжуулах, тоолох, хадгалалт хамгаалалт, ашиглалтын байдалд судалгаа хийх ажлыг 2008-2015 онд гүйцэтгэхээр төлөвлөн хэрэгжүүлж эхлээд байгаа билээ. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Globalization ’s Impact on Mongolian Identity Issues and the Image of Chinggis Khan Alicia J. Campi PART I: The Mongols, this previously unheard-of nation that unexpectedly emerged to terrorize the whole world for two hundred years, disappeared again into obscurity with the advent of firearms. Even so, the name Mongol became one forever familiar to humankind, and the entire stretch of the thirteenth through the fifteenth centuries has come to be known as the Mongol era.' PART II; The historic science was the science, which has been badly affect ed, and the people of Mongolia bid farewell to their history and learned by heart the bistort' with distortion but fuU of ideolog}'. Because of this, the Mong olians started to forget their religious rituals, customs and traditions and the pa triotic feelings of Mongolians turned to the side of perishing as the internation alism was put above aU.^ PART III: For decades, Mongolia had subordinated national identity to So viet priorities __Now, they were set adrift in a sea of uncertainty, and Mongol ians were determined to define themselves as a nation and as a people. The new freedom was an opportunity as well as a crisis." As the three above quotations indicate, identity issues for the Mongolian peoples have always been complicated. In our increas ingly interconnected, media-driven world culture, nations with Baabar, Histoij of Mongolia (Ulaanbaatar: Monsudar Publishing, 1999), 4. 2 “The Political Report of the First Congress of the Mongolian Social-Demo cratic Party” (March 31, 1990), 14. " Tsedendamdyn Batbayar, Mongolia’s Foreign Folicy in the 1990s: New Identity and New Challenges (Ulaanbaatar: Institute for Strategic Studies, 2002), 8. -

Danshig Naadam Games

2018.07.04 Festival Danshig Naadam Games This short trip offers plenty of Mongolian experiences in only two days and just outside of Ulaanbaatar. A few weeks after the Na- tional Naadam Festival, the Danshig Naadam festival will be held on the first weekend of August 2019. The festival grounds are located at Hui Doloon Hudag, a large plain about 40km west of Ulaanbaatar. Before we visit the festival on the main day, that features among many highlights the ritual Tsam Mask dances, we explore Hustai National Park for a full day. Here we meet a local nomadic family and go on a game drive to see the Przewal- ski's horses that have been successfully reintroduced to the wild. Like the National Naadam, Danshig Naadam includes archery, horse racing and wrestling competitions, but there is in addition a strong focus on the history and practice of Buddhism. In 2015, Danshig Naadam was celebrated for the first time in 93 years. The revival of Danshig Naadam by the administration of Ulaanbaatar city and the Gandantegchinlen Monastery under the auspices of the “Historic, Harmonious and Hospitable” initiative aims to reintroduce the religious aspects of Naadam by including several performances and events highlighting Buddhism’s influ- ence on the people and culture of Mongolia. Saturday August 3rd—Hustai National Park We pick you up from your hotel after breakfast and leave Ulaanbaatar in westerly direction to Hustai National Park. We drive for about two hours. We have lunch with a local herding family, who live on the fringes of Hustai with their herds of live- stock. -

Thesis Local Understanding of Hydro-Climate Changes

THESIS LOCAL UNDERSTANDING OF HYDRO-CLIMATE CHANGES IN MONGOLIA Submitted by Tumenjargal Sukh Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2012 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Steven Fassnacht Melinda Laituri Maria Fernandez-Gimenez Greg Butters Copyright by Tumenjargal Sukh 2012 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT LOCAL UNDERSTANDING OF HYDRO-CLIMATE CHANGES IN MONGOLIA Air temperatures have increased more in semi-arid regions than in many other parts of the world. Mongolia has an arid/semi-arid climate where much of the population is dependent upon the limited water resources, especially herders. This paper combines herder observations of changes in water availability in streams and from groundwater with an analysis of climatic and hydrologic change from station data to illustrate the degree of change of Mongolian water resources. We find that herders’ local knowledge of hydro-climatic changes is similar to the station based analysis. However, station data are spatially limited, so local knowledge can provide finer scale information on climate and hydrology. We focus on two regions in central Mongolia: the Jinst soum in Bayankhongor aimag in the desert steppe region and the Ikh-Tamir soum in Arkhangai aimag in the mountain steppe. As the temperatures have increased significantly (more in Ikh-Tamir than Jinst), precipitation amounts have decreased in Ikh-Tamir which corresponds to a decrease in streamflow, in particular, the average annual streamflow and the annual peak discharge. At Erdenemandal (Ikh-Tamir) the number of days with precipitation has decreased while at Horiult (Jinst) it has increased. -

The Khitans: Corner Stone of the Mongol Empire

ACTA VIA SERICA Vol. 6, No. 1, June 2021: 141–164 doi: 10.22679/avs.2021.6.1.006 The Khitans: Corner Stone of the Mongol Empire GEORGE LANE* The Khitans were a Turco-Mongol clan who dominated China north of the Yangtze River during the early mediaeval period. They adopted and then adapted many of the cultural traditions of their powerful neighbours to the south, the Song Chinese. However, before their absorption into the Mongol Empire in the late 13th century they proved pivotal, firstly in the eastward expansion of the armies of Chinggis Khan, secondly, in the survival of the Persian heartlands after the Mongol invasions of the 1220s and thirdly, in the revival and integration of the polity of Iran into the Chinggisid Empire. Da Liao, the Khitans, the Qara Khitai, names which have served this clan well, strengthened and invigorated the hosts which harboured them. The Liao willingly assimilated into the Chinggisid Empire of whose formation they had been an integral agent and in doing so they also surrendered their identity but not their history. Recent scholarship is now unearthing and recognising their proud legacy and distinct identity. Michal Biran placed the Khitans irrevocably and centrally in mediaeval Asian history and this study emphasises their role in the establishment of the Mongol Empire. Keywords: Khitans, Liao, Chinggids, Mongols, Ilkhanate * Dr. GEORGE LANE is a Research Associate at the School of History, Religion & Philosophy, SOAS University of London. 142 Acta Via Serica, Vol. 6, No. 1, June 2021 The Khitans: Corner Stone of the Mongol Empire The Turco-Mongol tribe that first settled the lands of northern China, north of the Huai River and adopted and adapted the cultural traditions of their domineering neighbour to the south, has only recently been acknowledged for their importance to the evolution of mediaeval Asian history, due in large part to the work of Michal Biran of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.