Defining Territories and Empires: from Mongol Ulus to Russian Siberia1200-1800 Stephen Kotkin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crimean Khanate, Ottomans and the Rise of the Russian Empire*

STRUGGLE FOR EAST-EUROPEAN EMPIRE: 1400-1700 The Crimean Khanate, Ottomans and the Rise of the Russian Empire* HALİL İNALCIK The empire of the Golden Horde, built by Batu, son of Djodji and the grand son of Genghis Khan, around 1240, was an empire which united the whole East-Europe under its domination. The Golden Horde empire comprised ali of the remnants of the earlier nomadic peoples of Turkic language in the steppe area which were then known under the common name of Tatar within this new political framework. The Golden Horde ruled directly över the Eurasian steppe from Khwarezm to the Danube and över the Russian principalities in the forest zone indirectly as tribute-paying states. Already in the second half of the 13th century the western part of the steppe from the Don river to the Danube tended to become a separate political entity under the powerful emir Noghay. In the second half of the 14th century rival branches of the Djodjid dynasty, each supported by a group of the dissident clans, started a long struggle for the Ulugh-Yurd, the core of the empire in the lower itil (Volga) river, and for the title of Ulugh Khan which meant the supreme ruler of the empire. Toktamish Khan restored, for a short period, the unity of the empire. When defeated by Tamerlane, his sons and dependent clans resumed the struggle for the Ulugh-Khan-ship in the westem steppe area. During ali this period, the Crimean peninsula, separated from the steppe by a narrow isthmus, became a refuge area for the defeated in the steppe. -

List of Rivers of Mongolia

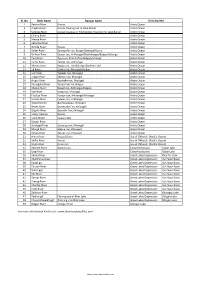

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

SDN Changes 2014

OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL CHANGES TO THE Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List SINCE JANUARY 1, 2014 This publication of Treasury's Office of Foreign AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah (a.k.a. SAHAB, Qari; IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN Assets Control ("OFAC") is designed as a a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH; a.k.a. reference tool providing actual notice of actions by 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. OFAC with respect to Specially Designated Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, "SUPPORTERS OF ISLAMIC LAW"), Tunisia Nationals and other entities whose property is Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) [FTO] [SDGT]. blocked, to assist the public in complying with the [SDGT]. AL-RAYA ESTABLISHMENT FOR MEDIA various sanctions programs administered by SAHAB, Qari (a.k.a. AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah; PRODUCTION (a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA; OFAC. The latest changes may appear here prior a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'A BRIGADE; a.k.a. to their publication in the Federal Register, and it 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'A IN BENGHAZI; a.k.a. is intended that users rely on changes indicated in Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN LIBYA; a.k.a. ANSAR this document that post-date the most recent Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) AL-SHARIAH; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIAH Federal Register publication with respect to a [SDGT]. -

Journal Biology 2004 3

Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences 2004 Vol. 2(1): 39-42 Hydrochemical Characteristics of Selenge River and its Tributaries on the Territory of Mongolia Bazarova J.G. 1, Dorzhieva S.G.1, Bazarov B.G. 1, Barkhutova D.D.2, Dagurova O.P.2, Namsaraev B.B. 2 and Zhargalova S.O.2 1Baikal Institute of Nature Management of SB RAS, Ulan-Ude, 2Institute of General and Experimental Biology of SB RAS, Ulan-Ude, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Hydrochemical research of the Selenge and its main tributary the Orkhon river on the territory of Mongolia has been conducted. Concentrations of the main water ions were measured. Distribution of - + heavy metals was determined. Dynamics of biogenic elements (NO3 , NH4 , phosphates) and degree of phenol pollution was determined. Key words: Baikal, biogenic, heavy metals, ions, phenol, Selenge River Introduction river is polluted along its entire length. To assess the current ecological condition in the Mongolian During the last 30-40 years Lake Baikal has part of the Selenge river basin, it is necessary to been influenced by various anthropogenic factors. implement hydrobiological and hydrochemical Industrial and household waste water have changed monitoring. It requires information not only of the chemical composition of Baikal with a chemical composition, but of biogenic components deterioration in water quality in the basin territory. in the processes of accumulation and According to sustainable development policy, transformation in water, bottom sediments and river protection of Baikal region is considered -

Koshymova Aknur the Role of Oghuzes in the VIII-XIII Centuries In

Koshymova Aknur The role of Oghuzes in the VIII-XIII centuries in the formation of ethno genesis of Turkic peoples ANNOTATION To the dissertation prepared to get PhD degree in “History” – 6D020300 General description of the dissertation. The dissertation paper explores the place of Oghuz in the ethnogenesis of the Turkic peoples in the context of the history of the Kazakhs, Azerbaijanis, Turkmen, Kyrgyz, and Turks. The relevance of the research. The studied problem reflects one of the topical issues that has a peculiar place both in national history and foreign historiography. Due to the antiquity and deep historical roots of the ethnogenetic process of the formation of the late Turkic peoples, the researchers recognized the direct involvement of the Oghuz clans and tribes in the history of the Kazakhs. During the study of the ethnogenesis of a single Turkic people, the process of its formation, development paths and features, you can see how great the role of migration and assimilation processes in the content of ethnic mixing of the autochthonous population and alien tribes, which determined the future ethnic composition, language, culture, and this circumstance allows us to consider this factor as the leading one. Therefore, the history of the Oghuz-speaking peoples who inhabited Central and Asia Minor, the Caucasus, from a modern point of view, must be investigated in close connection with the history of the Kazakh people, which makes it possible to obtain valuable scientific results. The history of the Oghuz originating in the VIII century from the territories of the Mongolian plateau and the northeastern part of modern Kazakhstan, which as a result of mass movements occupied the Syrdarya valley, then the territory of modern Turkmenistan, then Azerbaijan and Anatolia, which led to dramatic changes in ethnic processes in these regions, it is necessary to consider taking into account the historical and genetic continuity. -

Medieval Turkic Nations and Their Image on Nature and Human Being (VI-IX Centuries)

Asian Social Science; Vol. 11, No. 8; 2015 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Medieval Turkic Nations and Their Image on Nature and Human Being (VI-IX Centuries) Galiya Iskakova1, Talas Omarbekov1 & Ahmet Tashagil2 1 Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Faculty of History, Archeology and Ethnology, Kazakhstan 2 Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Faculty of Science, Turkey Correspondence: Galiya Iskakova, al-Farabi Avenue, 71, Almaty, 050038, Kazakhstan. Received: November 27, 2014 Accepted: December 10, 2014 Online Published: March 20, 2015 doi:10.5539/ass.v11n8p155 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n8p155 Abstract The article aims to consider world vision of medieval (VI-IX centuries) Turkic tribes on nature and human being and the issues, which impact on the emergence of their world image on nature, human being as well as their perceptions in this case. In this regard, the paper analyzes the concepts on territory, borders and bound in the Turks` society, the indicator of the boundaries for Turkic tribes and the way of expression the world concept on nature and human being of above stated nations. The research findings show that Turks as their descendants Kazakhs had a distinctive vision on environment and the relationship between human being and nature. Human being and nature were conceived as a single organism. Relationship of Turkic mythic outlook with real historical tradition and a particular geographical location captures the scale of the era of the birth of new cultural schemes. It was reflected in the various historical monuments, which characterizes the Turkic civilization as a complex system. -

Climate Warming Impacts on Distributions of Scots Pine (Pinus Sylvestris L.) Seed Zones and Seed Mass Across Russia in the 21St Century

Article Climate Warming Impacts on Distributions of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Seed Zones and Seed Mass across Russia in the 21st Century Elena I. Parfenova 1, Nina A. Kuzmina 2, Sergey R. Kuzmin 2 and Nadezhda M. Tchebakova 1,* 1 Laboratory of Forest Monitoring, Sukachev Institute of Forest FRC KSC SB RAS, 660036 Krasnoyarsk, Russia; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Forest Genetics and Breeding, Sukachev Institute of Forest FRC KSC SB RAS, 660036 Krasnoyarsk, Russia; [email protected] (N.A.K.); [email protected] (S.R.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Research highlights: We investigated bioclimatic relationships between Scots pine seed mass and seed zones/climatypes across its range in Russia using extensive published data to predict seed zones and seed mass distributions in a changing climate and to reveal ecological and genetic components in the seed mass variation using our 40-year common garden trial data. Introduction: seed productivity issues of the major Siberian conifers in Asian Russia become especially relevant nowadays in order to compensate for significant forest losses due to various disturbances during the 20th and current centuries. Our goals were to construct bioclimatic models that predict the seed mass of major Siberian conifers (Scots pine, one of the major Siberian conifers) in a warming climate during the current century. Methods: Multi-year seed mass data were derived from the literature and were collected during field work. Climate data (January and July data and annual precipitation) were Citation: Parfenova, E.I.; Kuzmina, derived from published reference books on climate and climatic websites. -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

About the Mongol Invasions

CK_4_TH_HG_P087_242.QXD 10/6/05 9:02 AM Page 162 V. China: Dynasties and Conquerors navigators could use it to be sure they were traveling in the right direction. The compass did not reach Europe until the 1200s. It was one of the navigational devices that enabled Europeans to embark on their voyages of exploration in search of an all-water route to Asia. Paper money came into use in China during the Song dynasty. The Chinese, Teaching Idea as well as other peoples, had been using metal coins for centuries, but the Chinese Ask students to write an expository were the first to use paper currency. Two other inventions converged to make the piece about why they think the Chinese use of paper currency possible. First, the Chinese had invented the process of invented paper money instead of con- making paper in 105 CE, and then, during the Tang dynasty in the 700s CE, they tinuing solely to use coins. Historians had learned how to print from large blocks of type—the words for a page were believe the Chinese switched to paper carved into a single block of wood the size of the page, then inked, and paper money because there was not enough applied. In the 1040s, the Chinese had invented the use of movable type for print- copper, bronze, and iron to make coins ing. The characters for individual words were carved into small pieces of wood and for the entire population. Also, paper assembled to make a page, then inked, and paper applied. Europeans would not money was easier to carry around and employ movable type until the time of Gutenberg, about 1450. -

Il-Khanate Empire

1 Il-Khanate Empire 1250s, after the new Great Khan, Möngke (r.1251–1259), sent his brother Hülegü to MICHAL BIRAN expand Mongol territories into western Asia, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel primarily against the Assassins, an extreme Isma‘ilite-Shi‘ite sect specializing in political The Il-Khanate was a Mongol state that ruled murder, and the Abbasid Caliphate. Hülegü in Western Asia c.1256–1335. It was known left Mongolia in 1253. In 1256, he defeated to the Mongols as ulus Hülegü, the people the Assassins at Alamut, next to the Caspian or state of Hülegü (1218–1265), the dynasty’s Sea, adding to his retinue Nasir al-Din al- founder and grandson of Chinggis Khan Tusi, one of the greatest polymaths of the (Genghis Khan). Centered in Iran and Muslim world, who became his astrologer Azerbaijan but ruling also over Iraq, Turkme- and trusted advisor. In 1258, with the help nistan, and parts of Afghanistan, Anatolia, of various Mongol tributaries, including and the southern Caucasus (Georgia, many Muslims, he brutally conquered Bagh- Armenia), the Il-Khanate was a highly cos- dad, eliminating the Abbasid Caliphate that mopolitan empire that had close connections had nominally led the Muslim world for more with China and Western Europe. It also had a than 500 years (750–1258). Hülegü continued composite administration and legacy that into Syria, but withdrew most of his troops combined Mongol, Iranian, and Muslim after hearing of Möngke’s death (1259). The elements, and produced some outstanding defeat of the remnants of his troops by the cultural achievements. -

North and Central Asia FAO-Unesco Soil Tnap of the World 1 : 5 000 000 Volume VIII North and Central Asia FAO - Unesco Soil Map of the World

FAO-Unesco S oilmap of the 'world 1:5 000 000 Volume VII North and Central Asia FAO-Unesco Soil tnap of the world 1 : 5 000 000 Volume VIII North and Central Asia FAO - Unesco Soil map of the world Volume I Legend Volume II North America Volume III Mexico and Central America Volume IV South America Volume V Europe Volume VI Africa Volume VII South Asia Volume VIIINorth and Central Asia Volume IX Southeast Asia Volume X Australasia FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION FAO-Unesco Soilmap of the world 1: 5 000 000 Volume VIII North and Central Asia Prepared by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Unesco-Paris 1978 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not irnply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations or of the United Nations Educa- tional, Scientific and Cultural Organization con- cerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delirnitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Printed by Tipolitografia F. Failli, Rome, for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Published in 1978 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Place de Fontenoy, 75700 Paris C) FAO/Unesco 1978 ISBN 92-3-101345-9 Printed in Italy PREFACE The project for a joint FAO/Unesco Soil Map of vested with the responsibility of compiling the techni- the World was undertaken following a recommenda- cal information, correlating the studies and drafting tion of the International Society of Soil Science. -

Timing and Dynamics of Glaciation in the Ikh Turgen Mountains, Altai T Region, High Asia

Quaternary Geochronology 47 (2018) 54–71 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Geochronology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quageo Timing and dynamics of glaciation in the Ikh Turgen Mountains, Altai T region, High Asia ∗ Robin Blomdina,b, , Arjen P. Stroevena,b, Jonathan M. Harbora,b,c, Natacha Gribenskia,b,d, Marc W. Caffeec,e, Jakob Heymanf, Irina Rogozhinag, Mikhail N. Ivanovh, Dmitry A. Petrakovh, Michael Waltheri, Alexei N. Rudoyj, Wei Zhangk, Alexander Orkhonselengel, Clas Hättestranda,b, Nathaniel A. Liftonc,e, Krister N. Janssona,b a Geomorphology and Glaciology, Department of Physical Geography, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden b Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden c Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, USA d Institute of Geological Sciences, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland e Department of Physics and Astronomy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, USA f Department of Earth Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden g MARUM, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany h Faculty of Geography, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia i Institute of Geography and Geoecology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia j Center of Excellence for Biota, Climate and Research, Tomsk State University, Tomsk, Russia k College of Urban and Environmental Science, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian, China l Laboratory of Geochemistry and Geomorphology, School of Arts and Sciences, National