Approved October 24, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

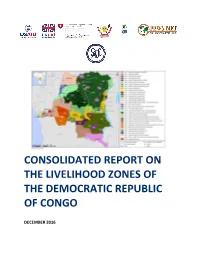

DRC Consolidated Zoning Report

CONSOLIDATED REPORT ON THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DECEMBER 2016 Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Livelihoods zoning ....................................................................................................................7 1.2 Implementation of the livelihood zoning ...................................................................................8 2. RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN DRC - AN OVERVIEW .................................................................. 11 2.1 The geographical context ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The shared context of the livelihood zones ............................................................................. 14 2.3 Food security questions ......................................................................................................... 16 3. SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES .................................................... 18 CD01 COPPERBELT AND MARGINAL AGRICULTURE ....................................................................... 18 CD01: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................... -

Common Humanitarian Fund, DRC Annual Report 2014

Common Humanitarian Fund, DRC Annual Report 2014 Annual Report 2014 Annual DRC Common Humanitarian Fund Humanitarian DRCCommon 1 Common Humanitarian Fund, DRC Annual Report 2014 Please send your questions and comments to : Alain Decoux, Joint Humanitarian Finance Unit (JFHU) + 243 81 706 12 00, [email protected] For the latest on-line version of this report and more on the CHF DRC, please visit: www.unocha.org/DRC or www.humanitarianresponse.info/fr/operations/democratic-republic-congo Cover photo: OCHA/Alain Decoux A displaced woman grinding cassava leaves in Tuungane spontaneous site, Komanda, Irumu Territory where more than 20,000 people were displaced due to conflict in the province. Oriental 02/2015. Kinshasa, DRC May, 2015 1 Common Humanitarian Fund, DRC Annual Report 2014 Table of contents Forword by the Humanitarian Coordinator....................................................................................... 3 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 4 2 Humanitarian Response Plan .................................................................................................. 7 3 Information on Contributions .................................................................................................... 8 4 Overview of Allocations .......................................................................................................... 10 4.1 Allocation strategy ......................................................................................................... -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 11 (A) - July 2003 I hid in the mountains and went back down to Songolo at about 3:00 p.m. I saw many people killed and even saw traces of blood where people had been dragged. I counted 82 bodies most of whom had been killed by bullets. We did a survey and found that 787 people were missing – we presumed they were all dead though we don’t know. Some of the bodies were in the road, others in the forest. Three people were even killed by mines. Those who attacked knew the town and posted themselves on the footpaths to kill people as they were fleeing. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch ITURI: “COVERED IN BLOOD” Ethnically Targeted Violence In Northeastern DR Congo 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] “You cannot escape from the horror” This story of fifteen-year-old Elise is one of many in Ituri. She fled one attack after another and witnessed appalling atrocities. Walking for more than 300 miles in her search for safety, Elise survived to tell her tale; many others have not. -

Musebe Artisanal Mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo

Gold baseline study one: Musebe artisanal mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo Gregory Mthembu-Salter, Phuzumoya Consulting About the OECD The OECD is a forum in which governments compare and exchange policy experiences, identify good practices in light of emerging challenges, and promote decisions and recommendations to produce better policies for better lives. The OECD’s mission is to promote policies that improve economic and social well-being of people around the world. About the OECD Due Diligence Guidance The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD Due Diligence Guidance) provides detailed recommendations to help companies respect human rights and avoid contributing to conflict through their mineral purchasing decisions and practices. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance is for use by any company potentially sourcing minerals or metals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. It is one of the only international frameworks available to help companies meet their due diligence reporting requirements. About this study This gold baseline study is the first of five studies intended to identify and assess potential traceable “conflict-free” supply chains of artisanally-mined Congolese gold and to identify the challenges to implementation of supply chain due diligence. The study was carried out in Musebe, Haut Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. This study served as background material for the 7th ICGLR-OECD-UN GoE Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains in Paris on 26-28 May 2014. It was prepared by Gregory Mthembu-Salter of Phuzumoya Consulting, working as a consultant for the OECD Secretariat. -

Mecanisme De Referencement

EN CAS DE VIOLENCE SEXUELLE, VOUS POUVEZ VOUS ORIENTEZ AUX SERVICES CONFIDENTIELLES SUIVANTES : RACONTER A QUELQU’UN CE QUI EST ARRIVE ET DEMANDER DE L’AIDE La/e survivant(e) raconte ce qui lui est arrivé à sa famille, à un ami ou à un membre de la communauté; cette personne accompagne la/e survivant(e) au La/e survivant(e) rapporte elle-même ce qui lui est arrivé à un prestataire de services « point d’entrée » psychosocial ou de santé OPTION 1 : Appeler la ligne d’urgence 122 OPTION 2 : Orientez-vous vers les acteurs suivants REPONSE IMMEDIATE Le prestataire de services doit fournir un environnement sûr et bienveillant à la/e survivant(e) et respecter ses souhaits ainsi que le principe de confidentialité ; demander quels sont ses besoins immédiats ; lui prodiguer des informations claires et honnêtes sur les services disponibles. Si la/e survivant(e) est d'accord et le demande, se procurer son consentement éclairé et procéder aux référencements ; l’accompagner pour l’aider à avoir accès aux services. Point d’entrée médicale/de santé Hôpitaux/Structures permanentes : Province du Haut Katanga ZS Lubumbashi Point d’entrée pour le soutien psychosocial CS KIMBEIMBE, Camps militaire de KIMBEIMBE, route Likasi, Tel : 0810405630 Ville de Lubumbashi ZS KAMPEMBA Division provinciale du Genre, avenue des chutes en face de la Division de Transport, HGR Abricotiers, avenue des Abricotiers coin avenue des plaines, Q/ Bel Air, Bureau 5, Centre ville de Lubumbashi. Tel : 081 7369487, +243811697227 Tel : 0842062911 AFEMDECO, avenue des pommiers, Q/Bel Air, C/KAMPEMBA, Tel : 081 0405630 ZS RUASHI EASD : n°55, Rue 2, C/ KATUBA, Ville de Lubumbashi. -

An Inventory of Fish Species at the Urban Markets of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo

FISHERIES AND HIV/AIDS IN AFRICA: INVESTING IN SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS PROJECT REPORT | 1983 An inventory of fi sh species at the urban markets of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Mujinga, W. • Lwamba, J. • Mutala, S. • Hüsken, S.M.C. • Reducing poverty and hunger by improving fisheries and aquaculture www.worldfi shcenter.org An inventory of fish species at the urban markets of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Mujinga, W., Lwamba, J., Mutala, S. et Hüsken, S.M.C. Translation by Prof. A. Ngosa November 2009 Fisheries and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Investing in Sustainable Solutions This report was produced under the Regional Programme “Fisheries and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Investing in Sustainable Solutions” by the WorldFish Center and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), with financial assistance from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This publication should be cited as: Mujinga, W., Lwamba, J., Mutala, S. and Hüsken, S.M.C. (2009). An inventory of fish species at the urban markets in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Regional Programme Fisheries and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Investing in Sustainable Solutions. The WorldFish Center. Project Report 1983. Authors’ affiliations: W. Mujinga : University of Lubumbashi, Clinique Universitaire. J. Lwamba : University of Lubumbashi, Clinique Universitaire. S. Mutala: The WorldFish Center DRC S.M.C. Hüsken: The WorldFish Center Zambia National Library of Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Cover design: Vizual Solution © 2010 The WorldFish Center All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational or non-profit purposes without permission of, but with acknowledgment to the author(s) and The WorldFish Center. -

Kolwezi : L'espace Habité Et Ses Problèmes Dans Le Premier Centre

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Horizon / Pleins textes KOLWEZI : L’ESPACE HABITfi ET SES PROBL’ÈMES DANS LE PREMIER CENTRE MINIER DU ZAÏRE Jean-Claude BRUNEAU et MANSILA Fu-Kiau Professeur ef Chef de frarraux à l’Université de Lubumbashi (Zaire] RÉsunrE Ville jeune, Kolrvezi fut créée en 1937 sur de très riches’gisements de cuivre et de cobalt, et reste le premier centre industriel et minier du Zaïre. La ville moyenne de l’époque coloniale, bien planifiée ef équipée, opposait les quartiers de cadres européens aux quartiers populaires africains (camps de la Société minière ef (1cifè indigène o), selon une struciure polynucléaire. Après un essor demographique et spafial impressionnant, Kolwezi est aujourd’hui une ville imporfante où les quartiers anciens sonf pris dans la marée de l’aufoconstruction qui envahit jusqu’aux concessions minières. Une part croissante de l’espace habité échappe à la GECAMINES, jadis Qproprièlaire o de la ville, et qui envisage de déplacer celle-ci pour exploiter les nouveaux gisements. Toul cela rend très nécessaire l’élaboration d’un schéma d’aménagement global de la ville de Kolwezi. MOTS-CL& : Zaïre - Centre minier - Croissance urbaine - Schéma d’aménagement. urbain. ABSTRACT KOLWEZI :THE INHABITED SPACE AND ITS PROBLEMS IN THE MAJORMINING CENTRE IN ZAIRE A Young town, Kolwezi was seftled in 1937 on very rich copper and cobalt deposits. It is still the major industrial and mining centre in Zaïre. In a mid-sized well-planned and equiped colonial fown, one could distinguish rvhile collar european districts and african rvorkers areas i.e. -

Kitona Operations: Rwanda's Gamble to Capture Kinshasa and The

Courtesy of Author Courtesy of Author of Courtesy Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers during 1998 Congo war and insurgency Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers guard refugees streaming toward collection point near Rwerere during Rwanda insurgency, 1998 The Kitona Operation RWANDA’S GAMBLE TO CAPTURE KINSHASA AND THE MIsrEADING OF An “ALLY” By JAMES STEJSKAL One who is not acquainted with the designs of his neighbors should not enter into alliances with them. —SUN TZU James Stejskal is a Consultant on International Political and Security Affairs and a Military Historian. He was present at the U.S. Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda, from 1997 to 2000, and witnessed the events of the Second Congo War. He is a retired Foreign Service Officer (Political Officer) and retired from the U.S. Army as a Special Forces Warrant Officer in 1996. He is currently working as a Consulting Historian for the Namib Battlefield Heritage Project. ndupress.ndu.edu issue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 / JFQ 99 RECALL | The Kitona Operation n early August 1998, a white Boeing remain hurdles that must be confronted by Uganda, DRC in 1998 remained a safe haven 727 commercial airliner touched down U.S. planners and decisionmakers when for rebels who represented a threat to their unannounced and without warning considering military operations in today’s respective nations. Angola had shared this at the Kitona military airbase in Africa. Rwanda’s foray into DRC in 1998 also concern in 1996, and its dominant security I illustrates the consequences of a failure to imperative remained an ongoing civil war the southwestern Bas Congo region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Le Répertoire Des Entreprises Mines Et Carrières RDC REPERTOIRE DES ENTREPISES MINES ET CARRIERES DE LA RD CONGO

REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO Ministère de l’Economie Nationale Le répertoire des entreprises Mines et carrières RDC REPERTOIRE DES ENTREPISES MINES ET CARRIERES DE LA RD CONGO Aménagement minier & transport N° ENTREPRISE ADRESSE 1 DE NOVO CONGO Adresse: KINSHASA - Bld. du 30 juin, Galeries du Centenaire 1B4, Gombe Téléphone: (+243)817000001 Fax: (+243)813013831 2 AEL MINING SERVICES Adresse: LUBUMBASHI Téléphone: (+243)995366250 3 AFRICAN MINERALS Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 2548, Bld (BARBADOS) Kamanyola, Quartier Baudouin Téléphone: (+243)815250075 4 BOSS MINING SPRL Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 238, Rte Likasa, C/Annexe, Téléphone: (+243)814054166 5 CONGO COBALT Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 238, Rte Likasi, CORPORATION (CCC) C/Annexe, Téléphone: (+243)817107844 6 ENTREPRISE GENERALE Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - Av. Kigoma 22 - B.P. MALTA FORREST 153, Téléphone: (+243)2342232 7 ENTREPRISE GENERALE Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 22, Av. Kigoma, MALTA FORREST (EGMF) C/Kampemba, Téléphone: (+243)817777777 8 GECAMINES Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 419, Bld Kamanyola, Téléphone: (+243)2341041 9 GOLDEN AFRICAN Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 1064, Rte Likasi, RESOURCES SPRL Village TUMBWE Téléphone: (+243)810180538 10 KAMOTO COPPER Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 618, Av. 30 Juin, Q/ COMPANY (KCC) Mutoshi, Kolwezi Téléphone: (+243)970011070 11 KATANGA METALS SPRL Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 01, Av Kamina, Kolwezi, Téléphone: (+243)971029960 12 KINSENDA COPPER Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 332, Av Victimes de COMPANY (KICC) la Rébellion, Quartier Bel Air, C/Kampemba Téléphone: (+243)998771114 13 MINING COMPANY Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - av. Industrie 90, KATANGA GROUP Commune Kampemb Téléphone: (+243)997040594 14 PHELPS DODGE CONGO Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 25, Av. Kashobwe SPRL Téléphone: (+243)996772037 15 RULVIS CONGO Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - av. Kato 13, Quartier industriel, Téléphone: (+243)997026624 16 SASE MINING SPRL Adresse: LUBUMBASHI - 49, Av. -

Province Du Katanga Profil Resume Pauvrete Et Conditions De Vie Des Menages

Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement Unité de lutte contre la pauvreté RDC PROVINCE DU KATANGA PROFIL RESUME PAUVRETE ET CONDITIONS DE VIE DES MENAGES Mars 2009 PROVINCE DU KATANGA Sommaire Province Katanga Superficie 496.877 km2 Population en 2005 8,7 millions Avant-propos..............................................................3 Densité 18 hab/km² 1 – La province de Katanga en un clin d’œil..............4 Nombre de districts 5 2 – La pauvreté au Katanga.......................................6 Nombre de villes 3 3 – L’éducation.........................................................10 Nombre de territoires 22 4 – Le développement socio-économique des Nombre de cités 27 femmes.....................................................................11 Nb de communes 12 5 – La malnutrition et la mortalité infantile ...............12 Nb de quartiers 43 6 – La santé maternelle............................................13 Nombre de groupements 968 7 – Le sida et le paludisme ......................................14 Routes urbaines 969 km 8 – L’habitat, l’eau et l’assainissement ....................15 Routes nationales 4.637 km 9 – Le développement communautaire et l’appui des Routes d’intérêt provincial 679 km Partenaires Techniques Financiers (PTF) ...............16 Réseau ferroviaire 2.530 km Gestion de la province Gouvernement Provincial Nb de ministres provinciaux 10 Nb de députés provinciaux 103 - 2 – PROVINCE DU KATANGA Avant-propos Le présent rapport présente une analyse succincte des conditions de vie des ménages du -

Jesus: God, the Only God, Or No God? a Study of Jehovah’S Witnesses’ and Branhamism’S Influence in Kolwezi, DRC

Jesus: God, the only God, or No God? A study of Jehovah’s Witnesses’ and Branhamism’s influence in Kolwezi, DRC MB MUFIKA Student ORCID.org/ 0000-0001-6004-2024 Thesis submitted for the fulfilment of the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Missiology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University Promoter: Prof. dr HG Stoker Graduation October 2017 http://www,nwu.ac.za/ PREFACE The Apostles’ Creed I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth; and in Jesus Christ, His only Son our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried. He descended into hell; the third day He rose again from the dead; He ascended into heaven, and sitteth at the right hand of God, the Father almighty; from whence He shall come to judge the living and the dead. I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy Catholic Church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body and life everlasting. Amen And, behold, I come quickly; and my reward is with me, to give every man according as his work shall be. I am the Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last. Blessed are they that do his commandments, that they may have right to the tree of life, and may enter in through the gates into the city. For without are dogs, and sorcerers, and whoremongers, and murderers, and idolaters, and whosoever loveth and maketh a lie. -

Integrated Hiv/Aids Project Haut Katanga/Lualaba

USAID COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT NO. AID-660-A-17-00001 INTEGRATED HIV/AIDS PROJECT HAUT KATANGA/LUALABA Fiscal Year 2018 Quarter 2 Performance Report January 1–March 31, 2018 Submitted: May 15, 2018 This document was produced by the Integrated HIV/AIDS Project in Haut Katanga and Lualaba consortium through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development. The opinions herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Table of Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................. iv Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... vi Key Achievements and Program Progress ...................................................................................... 1 Objective One: Continuum of care for HIV/AIDS services ensured .......................................... 1 Sub-objective 1.1: Increased availability of comprehensive HIV prevention services. .......... 1 Sub-objective 1.2: Expanded comprehensive HIV/AIDS care and treatment services. .......... 9 Sub-objective 1.3: Improved integration of HIV/TB services. ............................................. 12 Sub-objective 1.4: Expanded network and referral systems for other health and social services. ................................................................................................................................