Plebeian Volume III Editorial Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FALL 2008 Columbia University in the City of New York Co

FALL 2008 Columbia University in the City of New York CO 435 West 116th Street, Box A-2 L UM New York, NY 10027 BI A L RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED A W S C HO O L M ag azine www.law.columbia.edu/alumni fall 2008 BREAKING THE CODE NEW FACULTY MEMBER MICHAEL GRAETZ HAS AN INNOVATIVE PLAN FOR REVAMPING AMERICA’s TAX CODE TALKINGTALKING TETELECLECOM: TIM WU CHATS WITH JEFFREY TOOBIN SCOTUS ANALYSIS FROM BLASI, BRIFFAULT, GREENAWALT, HAMBURGER, AND PERSILY Opportunity The Future of Diversity and Opportunity in Higher dean Columbia Law School Magazine David M. Schizer is published three times annually for alumni and friends of associate dean Education: A National Columbia Law School by the for development and Office of Development and alumni relations Alumni Relations. Forum on Innovation and Bruno M. Santonocito Opinions expressed in Columbia Law Collaboration executive director School Magazine do not necessarily of communications reflect the views of Columbia Law and public affairs School or Columbia University. Elizabeth Schmalz This magazine is printed December 3-5, 2008 guest editor on FSC certified paper. Matthew J.X. Malady editorial director James Vescovi assistant editor Mary Johnson Change of address information should be sent to: copy editors Lauren Pavlakovich, Columbia Law School Joy Y. Wang 435 West 116 Street, Box A-2 New York, NY 10027 During the first week in December, design and art direction Attn: Office of Alumni Relations Empire Design Studio Alumni Office university presidents, provosts, and photography 212-854-2680 Peter Freed, Robyn Twomey, Magazine Notices Eric van den Brulle, Jon Roemer 212-854-2650 academic innovators will gather for David Yellen [email protected] an historic conference focused on new printing Copyright 2008, Columbia Maar Printing Service, Inc. -

DEMOCRITUS Democritus

CHAPTER FOUR DEMOCRITUS Democritus (c. 460-396 B.C.) was a younger contemporary ofProtagoras; both were born in Abdera. 1 Although he had encyclopedic interests and was the author of many works, the 298 fragments ascribed to him in Diels-Kranz are at most all that has survived of his writings? Almost all of these fragments concern ethical matters. But despite this, Democritus has generally not been known for his moral theory. He has always, and rightly, been considered an important figure in the history of natural philosophy for his theory of atomism. Commentators on the ethical fragments have often found them to be of little or no philosophical importance3 and have sometimes questioned their authenticity. The issue of whether these fragments are authentic is not important in the context of the present study, which is only interested in these fragments insofar as they re present the views of an early Greek moral theorist concerned with the issue of the compatibility of self-interest and morality. Thus, it would make little difference here whether the fragments be attributed to Democritus or one of his contemporar ies, although my own view is that they probably should be assigned to Democri tus.4 On the other hand, it is a crucial question in the present context whether the fragments have philosophical importance. It is true, of course, that the ethical fragments are written in a style closer to the philosophically unrigorous fragments of Antiphon's On Concord than to those from On Truth. But it cannot be concluded from this fact that they are trivial. -

Functional Responses and Intraspecific

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGYENTOMOLOGY ISSN (online): 1802-8829 Eur. J. Entomol. 115: 232–241, 2018 http://www.eje.cz doi: 10.14411/eje.2018.022 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Functional responses and intraspecifi c competition in the ladybird Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) provided with Melanaphis sacchari (Homoptera: Aphididae) as prey PENGXIANG WU 1, 2, J ING ZHANG 1, 2, M UHAMMAD HASEEB 3, S HUO YAN 4, LAMBERT KANGA3 and R UNZHI ZHANG 1, * 1 Department of Entomology, State Key Laboratory of Integrated Management of Pest Insects and Rodents, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, #1-5 Beichen West Rd., Chaoyang, Beijing 100101, China; e-mails: [email protected] (Wu P.X.), [email protected] (Zhang J.), [email protected] (Zhang R.Z.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 Center for Biological Control, Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, FL 32307-4100, USA; e-mails: [email protected] (Haseeb M.), [email protected] (Kanga L.) 4 National Agricultural Technology Extension and Service Center, Beijing 100125, China; e-mail: [email protected] (Yan S.) Key words. Coleoptera, Coccinellidae, Harmonia axyridis, Hemiptera, Aphididae, Melanaphis sacchari, functional response, intraspecifi c competition Abstract. Functional responses at each developmental stage of predators and intraspecifi c competition associated with direct interactions among them provide insights into developing biological control strategies for pests. The functional responses of Harmonia axyridis (Pallas) at each developmental stage of Melanaphis sacchari (Zehntner) and intraspecifi c competition among predators were evaluated under laboratory conditions. The results showed that all stages of H. axyridis displayed a type II func- tional response to M. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Remembering Music in Early Greece

REMEMBERING MUSIC IN EARLY GREECE JOHN C. FRANKLIN This paper contemplates various ways that the ancient Greeks preserved information about their musical past. Emphasis is given to the earlier periods and the transition from oral/aural tradition, when self-reflective professional poetry was the primary means of remembering music, to literacy, when festival inscriptions and written poetry could first capture information in at least roughly datable contexts. But the continuing interplay of the oral/aural and written modes during the Archaic and Classical periods also had an impact on the historical record, which from ca. 400 onwards is represented by historiographical fragments. The sources, methods, and motives of these early treatises are also examined, with special attention to Hellanicus of Lesbos and Glaucus of Rhegion. The essay concludes with a few brief comments on Peripatetic historiography and a selective catalogue of music-historiographical titles from the fifth and fourth centuries. INTRODUCTION Greek authors often refer to earlier music.1 Sometimes these details are of first importance for the modern historiography of ancient 1 Editions and translations of classical authors may be found by consulting the article for each in The Oxford Classical Dictionary3. Journal 1 2 JOHN C. FRANKLIN Greek music. Uniquely valuable, for instance, is Herodotus’ allusion to an Argive musical efflorescence in the late sixth century,2 nowhere else explicitly attested (3.131–2). In other cases we learn less about real musical history than an author’s own biases and predilections. Thus Plato describes Egypt as a never-never- land where no innovation was ever permitted in music; it is hard to know whether Plato fabricated this statement out of nothing to support his conservative and ideal society, or is drawing, towards the same end, upon a more widely held impression—obviously superficial—of a foreign, distant culture (Laws 656e–657f). -

Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry

Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry Esther Leslie Synthetic Worlds Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry Esther Leslie reaktion books Published by reaktion books ltd www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2005 Copyright © Esther Leslie 2005 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Colour printed by Creative Print and Design Group, Harmondsworth, Middlesex Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Kings Lynn British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Leslie, Esther, 1964– Synthetic worlds: nature, art and the chemical industry 1.Art and science 2.Chemical industry - Social aspects 3.Nature (Aesthetics) I. Title 7-1'.05 isbn 1 86189 248 9 Contents introduction: Glints, Facets and Essence 7 one Substance and Philosophy, Coal and Poetry 25 two Eyelike Blots and Synthetic Colour 48 three Shimmer and Shine, Waste and Effort in the Exchange Economy 79 four Twinkle and Extra-terrestriality: A Utopian Interlude 95 five Class Struggle in Colour 118 six Nazi Rainbows 167 seven Abstraction and Extraction in the Third Reich 193 eight After Germany: Pollutants, Aura and Colours That Glow 218 conclusion: Nature’s Beautiful Corpse 248 References 254 Select Bibliography 270 Acknowledgements 274 Index 275 introduction Glints, Facets and Essence opposites and origins In Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow a character remarks on an exploding missile whose approaching noise is heard only afterwards. The horror that the rocket induces is not just terror at its destructive power, but is a result of its reversal of the natural order of things. -

Chthonic Restitutions: Madness and Oblivion

Chthonic Restitutions: Madness and Oblivion Javier Berzal de Dios Abstract This essay theorizes madness as a chthonic emplacement to dishevel existentially insufcient and detached interpretations of disorder. Refecting on Nietzsche’s emphasis on poetry over systematic thought, I take up Lorca and Baudelaire’s visceral language on death and the earthly to revisit chthonic myths as expressing an underworld uncontrollable sphere beyond systematicity. Written from the phenomenologically precarious position of my own mental illness, this essay develops a sincere rhetoric to approach the chthonic from within rather than at sterilized distance. This positioning retains the indexicality of the intense and disorganized as a critical facet, in turn exploring the nuances of the experience without discursive reductions or romantic musings, from the ground down. Cassandra: ototototoi popoi da. – Aeschylus, Agamemnon 1072 Following the social turn of the 1960s, administrators and teachers of academic discourse began to replace “reason” and “rationality” with “critically,” or “critical thinking,” as their highest aim; however, the presumption of a rational subject remained stable. – Margaret Price, Mad at School 39 Am I mad now? In truth, the question of madness calls forth to a future memory: will I have been mad? Or really: how mad will I think I had been? Lucidity is anachronistic, an ex post facto verdict, casting out to madness what thought itself on mark… Madness itself voices the lan- guage of truth—this madness of mine—an eternally rational utterance, charts and graphs at hand. I picture philosophers terribly sane, so much they take for granted, so restrained and hygienic their connections… so reliable a language. -

Platonic Love in a Colorado Courtroom: Martha Nussbaum, John Finnis, and Plato's Laws in Evans V

Articles Platonic Love in a Colorado Courtroom: Martha Nussbaum, John Finnis, and Plato's Laws in Evans v. Romer Randall Baldwin Clark* I. RELEVANT FOR FIFTEEN MINUTES-OR THIRTY CENTURIES? To the ridicule of the highbrow popular press' and the surprise of classical scholars,2 Plato's Laws,3 a work which was mocked, even in * University of Virginia School of Law, Class of 2002. Ph.D., University of Chicago, 1998. Research Associate, Dartmouth College Department of Government, 1997-99. Author, THE LAW MOST BEAUTIFUL AND BEST: MEDICAL ARGUMENT AND MAGICAL RHETORIC IN PLATO'S LAWS (Rowman & Littlefield - Lexington Books, forthcoming 2001). This article has benefited from the comments of many friends, colleagues, and teachers. For their assistance, I would like to thank Danielle Allen, Larry Arnhart, Richard 0. Brooks, Robert A. Burt, Allison D. Clark, Andrew P. Clark, Elizabeth A. Clark, Glenn W. Clark, Matthew Crawford, Richard Dougherty, Martha A. Field, Shawntel R. Fugate, Martin P. Golding, L. Kent Greenawalt, A.E. Dick Howard, Leon R. Kass, Matthew Kutcher, Melissa S. Lane, Mark J. Lutz, Roger D. Masters, Lynn Mather, Angelia K. Means, Ted H. Miller, S. Sarah Monoson, David Peritz, Richard A. Posner, Christopher Rohrbacher, Ariel C. Silver, Nathan Tarcov, Bradley A. Thayer, Elizabeth E. Theran, Paul Ulrich, Eduardo A. Velasquez, Lloyd L. Weinreb, Martin D. Yaffe, and the members of my edit team at the Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities. I only regret that I was unable to address all of their criticisms. Particularly profound appreciation is owed to my friend and colleague, James B. Murphy, whose queries helped me conceive this work and whose encouragement brought it to light: aneu gar phil6n oudeis heloit' an zen. -

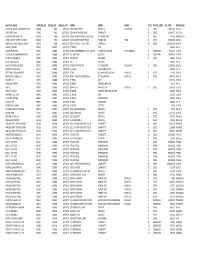

Supplier Name

SUPPLIER_NAME SUPPLIER_NO CHEQUE_NO CHEQUE_DATE ADDR1 ADDR2 ADDR3 STATE POSTAL_CODE INV_PAID INVOICE_NO OFFICE OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT SRF 04368 9683 6/3/2019 1201 MAIN STREET SUITE 910 COLUMBIA SC 29201 13,825.00 5-31-19 SOUTHEAST JACK C4690 9684 6/17/2019 7000 W WT HARRIS BLVD CHARLOTTE NC 28269 14,064.73 L6-17-19 GLOBAL AEROSPACE, INC. 09568 9686 6/17/2019 10895 GRANDVIEW DR, SUITE 150 OVERLAND PARK KS 66210 975.00 I00061547/01 YORK COUNTY CLERK OF COURT 00538 9687 6/26/2019 YORK COUNTY COURTHOUSE P O BOX 649 YORK SC 29745 35,000.00 6-26-19 JAMES, MCELROY & DIEHL TRUST 09567 9688 6/26/2019 525 N TRYON ST., SUITE 700 CHARLOTTE NC 28202 125,000.00 6-26-19 GIBSON, STEVEN 00957 230879 6/7/2019 EE #2679 OMB 209.96 6-2-19 UNUM PROVIDENT 01935 230880 6/7/2019 ATTN: VWB PREMIUM CLTN. & ACCT 1 FOUNTAIN SQUARE CHATTANOOGA TN 374021362 3,742.76 4-25-19 COMPORIUM COMMUNICATIONS 01951 230881 6/7/2019 P.O. BOX 1042 ROCK HILL SC 297317042 14,949.05 5-29-19 SC DEPT OF REVENUE 02000 230882 6/7/2019 TAX RETURN COLUMBIA SC 29214 486.00 5-31-19 SCOTT, MICHAEL W. 03826 230883 6/7/2019 CRH FIRE DEPT 200.00 6-5-19 BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD 04295 230884 6/7/2019 OF SOUTH CAROLINA P.O. BOX 6000 COLUMBIA SC 29260 11,959.40 5-21-19 BROWN, PAULA KNOX 06154 230885 6/7/2019 EE # 5036 SOLICITOR'S OFFICE 100.00 6-5-19 PRT TENNIS TOURNAMENT 06465 230886 6/7/2019 ATTN: 897 MAPLEWOOD LANE ROCK HILL SC 29730 112.00 5-29-19 NEXT LEVEL TENNIS, LLC 06525 230887 6/7/2019 ATTN: TEODORA DONCHEVA 872 DILLARD RD ROCK HILL SC 29730 7,897.60 N6-3-19 BROWN, LISA 07325 230888 6/7/2019 EE #5855 OMB 1,673.20 5-29-19 WINKLER, JEREMY 07922 230889 6/7/2019 EE #4207 GENERAL SERVICES 81.20 6-3-19 H.O.P.E. -

Thucydides and the World of Nature

CHAPTER 2 Natural Upheavals in Thucydides (and Herodotus) Rosaria Vignolo Munson To my favorite historian and a master of nonverbal communication, I dedi cate this inquiry: is the physical world a sender of signs? I am sure that Don ald Lateiner has his own answers, just as Herodotus and Thucydides had theirs. These authors were free from our environmental guilt and less bom barded than we are by the spectacle of humanitarian tragedies in every cor ner of the earth. Both of them, however, mention natural cataclysms in con nection with human actions and sociopolitical turmoil, most especially war. It is the thesis of this essay that, despite major differences, shared cultural assumptions emerge from the relations Herodotus and Thucydides establish between the natural and the human spheres. 1. World of Men and World of Nature In his introductory sentence, Thucydides calls the Peloponnesian War and its preliminary a Kivriau;... peyiaTr) for the Greek and partly for the non-Greek world (1.1.2). For most scholars (e.g., Hornblower 1991: 6), this is a reference to the "convulsion" caused by the war, and although Jeff Rusten makes a powerful argument (in this volume) that Kivr|au; here means "mobilization,"^ I. Elsewhere in Thucydides, kine- words refer, in fact, to unproblematic material transports. In one case, kined, while retaining its literal sense, is used somewhat abnormally (or, as Rusten shows, poetically) to denote a geological movement (2.8.3; s®® below, sec. 3). 41 42 KINESIS it would be a mistake to strip the term of all metaphorical undertones. In Aristotle's (in itself metaphorical) definition, metaphora consists in "the carry ing over [epiphora] of the name [onoma] of something to something else" (Poet ics 2i.i457b6-7). -

Downloading of Software That Would Enable the Display of Different Characters

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School CERTIFICATE FOR APPROVING THE DISSERTATION We hereby approve the Dissertation Of Jay T. Dolmage Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Director Dr. Cindy Lewiecki-Wilson Reader Dr. Kate Ronald Reader Dr. Morris Young Reader Dr. James Cherney Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT METIS: DISABILITY, RHETORIC AND AVAILABLE MEANS by Jay Dolmage In this dissertation I argue for a critical re-investigation of several connected rhetorical traditions, and then for the re-articulation of theories of composition pedagogy in order to more fully recognize the importance of embodied differences. Metis is the rhetorical art of cunning, the use of embodied strategies—what Certeau calls everyday arts—to transform rhetorical situations. In a world of chance and change, metis is what allows us to craft available means for persuasion. Building on the work of Detienne and Vernant, and Certeau, I argue that metis is a way to recognize that all rhetoric is embodied. I show that embodiment is a feeling for difference, and always references norms of gender, race, sexuality, class, citizenship. Developing the concept of metis I show how embodiment forms and transforms in reference to norms of ability, the constraints and enablements of our bodied knowing. I exercise my own metis as I re-tell the mythical stories of Hephaestus and Metis, and re- examine the dialogues of Plato, Aristotle, Cicero and Quintillian. I weave through the images of embodiment trafficked in phenomenological philosophy, and I apply my own models to the teaching of writing as an embodied practice, forging new tools for learning. I strategically interrogate the ways that academic spaces circumscribe roles for bodies/minds, and critique the discipline of composition’s investment in the erection of boundaries. -

Numerical Response of Olla V-Nigrum (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) to Infestations of Asian Citrus Psyllid, (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) in Florida

608 Florida Entomologist 84(4) December 2001 NUMERICAL RESPONSE OF OLLA V-NIGRUM (COLEOPTERA: COCCINELLIDAE) TO INFESTATIONS OF ASIAN CITRUS PSYLLID, (HEMIPTERA: PSYLLIDAE) IN FLORIDA J. P. MICHAUD University of Florida, Citrus Research and Education Center, 700 Experiment Station Road, Lake Alfred, FL 33881 ABSTRACT Data are presented on the relative abundance of the coccinellid Olla v-nigrum (Mulsant) in Florida citrus, before and after invasion by the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Ku- wayama. Adults and larvae of O. v-nigrum were observed preying on immature psyllids throughout their range in Florida. Immature psyllids were eliminated by predation from many flushed citrus terminals that exhibited damage symptoms; pupae of O. v-nigrum and Harmonia axyridis Pallas were recovered from adjacent leaves. Olla v-nigrum, a relatively rare species before the invasion by D. citri, is now a dominant species throughout Florida in citrus groves where the psyllid is present, but remains rare in regions where D. citri is ab- sent. The strong numerical response of this native ladybeetle to D. citri populations indi- cates that it is assuming a key role in biological control of the psyllid. Key Words: abundance, biological control, coccinellids, Diaphorina citri, Harmonia axyridis, Olla v-nigrum RESUMEN Se presentan datos sobre la abundancia relativa del coccinélido Olla v-nigrum (Mulsant) en cítricos en la Florida, antes y después de la invasión del psílido Asiático, Diphorina citri Kuwayama. Adultos y larvas de Olla v-nigrum fueron observados alimentándose de las for- mas inmaduras del psílido a través de la Florida. Se observaron muchos brotes terminales en los cítrcos con daños del psílido, pero estos fueron eliminados por depredación; pupas de O.