The Winding Road on the Media Landscape: the Establishment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elisa Elamus Kaabliga Kanalipaketid Kanalid Seisuga 01.07.2021

Elisa Elamus kaabliga kanalipaketid kanalid seisuga 01.07.2021 XL-pakett L-pakett M-pakett S-pakett KANALI NIMI KANALI NR AUDIO SUBTIITRID KANALI NIMI KANALI NR AUDIO SUBTIITRID ETV HD 1 EST PBK 60 RUS Kanal 2 HD 2 EST RTR-Planeta 61 RUS TV3 HD 3 EST REN TV 62 RUS ETV2 HD 4 EST NTV Mir 63 RUS TV6 HD 5 EST 3+ HD 66 RUS Kanal 11 HD 6 EST STS 71 RUS Kanal 12 HD 7 EST Dom kino 87 RUS Elisa 14 EST TNT4 90 RUS Cartoon Network 17 ENG; RUS TNT 93 RUS KidZone TV 20 EST; RUS Pjatnitsa 104 RUS Euronews HD 21 ENG Kinokomedia HD 126 RUS CNBC Europe 32 ENG Eesti kanal 150 EST Alo TV 46 EST Meeleolukanal HD 300 EST MyHits HD 47 EST Euronews 704 RUS Deutche Welle 56 ENG Duo 7 HD 934 RUS ETV+ 59 ENG Fox Life 8 ENG; RUS EST Viasat History HD 33 ENG; RUS EST; FIN Fox 9 ENG; RUS EST History 35 ENG; RUS EST Duo 3 HD 10 ENG; RUS EST Discovery Channel 37 ENG; RUS EST TLC 15 ENG; RUS EST BBC Earth HD 44 ENG Nickelodeon 18 ENG; EST; RUS VH1 48 ENG CNN 22 ENG TV7 57 EST BBC World News 23 ENG Orsent TV 69 RUS Bloomberg TV 24 TVN 70 RUS Eurosport 1 HD 28 ENG; RUS 1+2 72 RUS Duo 6 HD 11 ENG; RUS Mezzo 45 FRA FilmZone HD 12 ENG; RUS EST MCM Top HD 49 FRA FilmZone+ HD 13 ENG; RUS EST Trace Urban HD 50 ENG AMC 16 ENG; RUS MTV Europe 51 ENG Pingviniukas 19 EST; RUS Eurochannel HD 52 RUS HGTV HD 27 ENG EST Life TV 58 RUS Eurosport 2 HD 29 ENG; RUS TV XXI 67 RUS Setanta Sports 1 31 ENG; RUS Kanal Ju 73 RUS Viasat Explore HD 34 ENG; RUS EST; FIN 24 Kanal 74 UKR National Geographic 36 ENG; RUS EST Belarus 24 HD 75 RUS Animal Planet HD 38 ENG; RUS KidZone+ HD 503 EST; RUS Travel Chnnel HD 39 ENG; RUS SmartZone HD 508 EST; RUS Food Network HD 40 ENG; RUS Fight Sports HD 916 ENG Investigation Discovery HD 41 ENG; RUS EST VIP Comedy HD 921 ENG; RUS EST CBS Reality 42 ENG; RUS Epic Drama HD 922 ENG; RUS EST National Geographic HD 900 ENG; RUS Arte HD 908 FRA; GER Nat Geo Wild HD 901 ENG; RUS Mezzo Live HD 909 FRA History HD 904 ENG FIN Stingeray iConcerts HD 910 FRA Setanta Sports 1 HD 907 ENG; RUS. -

TALLINNA TEHNIKAÜLIKOOL Infotehnoloogia Teaduskond

TALLINNA TEHNIKAÜLIKOOL Infotehnoloogia teaduskond Arvutitehnika instituut IAG40LT Igor Bõstrov 061652IASB Digitelevisiooni võimalused ja tulevik Bakalaurusetöö Juhendaja: Dotsent Vladimir Viies Tallinn 2015 Bakalaurusetöö ülesanne Üliõpilane: Igor Bõstrov Lõputöö teema eesti keeles: “Digitelevisiooni võimalused ja tulevik” Lõputöö teema inglise keeles: “The future of digital television and it opportunities” Juhendaja (nimi, töökoht, teaduslik kraad, allkiri): Vladimir Viies ATI dotsent PhD Lahendatavad küsimused ning lähtetingimused: Digitelevisioni ajalugu, digitelevisiooni kirjeldamine IPTV näitel, selle omadused, nõuded, arendamise võimalused, IPTV kasutajaliides Elioni näitel, IPTV rakendused Eesti turul ning soovitused IPTV kasutajatele Elioni näitel. 2 Autori deklaratsioon Kinnitan, et antud tööd tegin iseseisvalt, ja varem seda tööd keegi ei ole kaitsmiseks esitanud. Kasutatud teiste autorite tööd, ajakirjad ja kirjandus on selles töös määratletud. Kuupäev allkiri 3 Abstract One popular question for each family, or individual person, who wishes to spend their leisure time for entertainment, sitting at home, or in order to be aware of what has happened in the world, or just to know which weather tomorrow will be - for sure comes to television. Television - is the history of development of technologies. Tube, color image, video recorders, cable, satellites, digital and mobile technologies were revolutionary of his time, not only technical but also social and cultural meaning. Television became the flow of technology scales, has radically changed people's living conditions, creating a completely new options to affect the audience. Digital TV, or digital television, audio and video transmission method using discrete signals, as apposed analog television that uses an analog signal. The question is to what TV should you choose? This is a very personal question, but you have to make your choice easier, in favor of one operator or another, should be a clear understanding of transmission of television and what benefits there are in one way or another. -

Levi TV Kanalid

levikom.ee 1213 Paksenduse (bold) ja punase teksti tähistusega telekanaleid on võimalik järelvaadata 7 päeva täies mahus (järelvaatamise teenus on eraldi kuutasu eest)! Telekanalite Levi TV Paras Levi TV Priima Levi TV Ekstra sisaldumine pakettides: - Põhikanaleid 33 kanalit 63 kanalit 69 kanalit - Muid kanaleid 5 kanalit 5 kanalit 10 kanalit KÕIK KOKKU: 38 telekanalit 68 telekanalit 79 telekanalit Eesti telekanalid: ETV ✓ ✓ ✓ ETV2 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 2 ✓ ✓ ✓ TV3 ✓ ✓ ✓ TV6 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 11 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 12 ✓ ✓ ✓ Alo TV ✓ ✓ ✓ Taevas TV7 ✓ ✓ ✓ Eesti Kanal ✓ ✓ ✓ Eesti Kanal Pluss ✓ ✓ ✓ (11 kanalit) (11 kanalit) (11 kanalit) Eesti kanalid HD formaadis (duplikaadina): ETV HD ✓ ✓ ✓ ETV2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 11 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 12 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ TV3 HD ✓ TV6 HD ✓ (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) Laste ja noorte telekanalid: Kidzone ✓ ✓ ✓ Kidzone+ HD ✓ ✓ Smartzone HD ✓ ✓ KiKa HD ✓ ✓ Nick JR ✓ ✓ Nickelodeon ✓ ✓ TEL 1213 TEL +372 684 0678 Levikom Eesti OÜ Pärnu mnt 139C, 11317 Tallinn [email protected] | levikom.ee Pingviniukas ✓ ✓ ✓ Multimania ✓ ✓ ✓ Mamontjonok ✓ ✓ ✓ (4 kanalit) (9 kanalit) (9 kanalit) Filmide ja sarjade telekanalid: Epic Drama HD ✓ ✓ ✓ TLC ✓ ✓ ✓ Sony Channel HD ✓ ✓ Sony Turbo HD ✓ ✓ FOX ✓ ✓ FOX Life ✓ ✓ Filmzone ✓ ✓ Filmzone+ HD ✓ ✓ Kino 24 ✓ ✓ ✓ Pro100TV ✓ ✓ ✓ Dom Kino ✓ ✓ ✓ (5 kanalit) (9 kanalit) (11 kanalit) Sporditeemalised telekanalid: Eurosport 1 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Eurosport 2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Setanta Sports HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Fuel TV HD ✓ ✓ Nautical Channel ✓ ✓ (3 kanalit) (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) Teaduse, looduse ja tõsielu teemalised telekanalid: Discovery -

Tallinna Linna 2020. Aasta Konsolideeritud Majandusaasta Aruande Kinnitamine” LISA

Tallinna Linnavolikogu 17. juuni 2021 otsuse nr 85 “Tallinna linna 2020. aasta konsolideeritud majandusaasta aruande kinnitamine” LISA Tallinna linna 2020. aasta konsolideeritud majandusaasta aruanne Sisukord 1. Tegevusaruanne 5 1.1. Konsolideerimisgrupp ja linnaorganisatsioon 5 1.1.1 Konsolideerimisgrupp 5 1.1.2 Linnaorganisatsiooni juhtimine 7 1.1.3 Töötajaskond 9 1.2. Põhilised finantsnäitajad 13 1.3. Ülevaade majanduskeskkonnast 16 1.4. Riskide juhtimine 18 1.4.1 Ülevaade sisekontrollisüsteemist ja tegevustest siseauditi korraldamisel 18 1.4.2 Finantsriskide juhtimine 20 1.5. Ülevaade Tallinna arengukava täitmisest 22 1.6. Ülevaade linna tütarettevõtjate, linna valitseva mõju all olevate sihtasutuste ja mittetulundusühingu tegevusest 58 1.7. Ülevaade linna olulise mõju all olevate äriühingute ja sihtasutuste tegevusest 72 2. Konsolideeritud raamatupidamise aastaaruanne 73 2.1. Konsolideeritud bilanss 73 2.2. Konsolideeritud tulemiaruanne 74 2.3. Konsolideeritud rahavoogude aruanne (kaudsel meetodil) 75 2.4. Konsolideeritud netovara muutuste aruanne 76 2.5. Eelarve täitmise aruanne 77 2.6. Konsolideeritud raamatupidamise aastaaruande lisad 78 Lisa 1. Arvestuspõhimõtted 78 Lisa 2. Raha ja selle ekvivalendid 85 Lisa 3. Finantsinvesteeringud 86 Lisa 4. Maksu- ja trahvinõuded 87 Lisa 5. Muud nõuded ja ettemaksed 88 Lisa 6. Varud 90 Lisa 7. Osalused valitseva mõju all olevates üksustes 91 Lisa 8. Osalused sidusüksustes 93 Lisa 9. Kinnisvarainvesteeringud 94 Lisa 10. Materiaalne põhivara 95 Lisa 11. Immateriaalne põhivara 98 Lisa 12. Maksu- ja trahvikohustised ning saadud ettemaksed 98 Lisa 13. Muud kohustised ja saadud ettemaksed 99 Lisa 14. Eraldised 100 Lisa 15. Võlakohustised 101 Lisa 16. Tuletisinstrumendid 105 Lisa 17. Maksutulud 105 Lisa 18. Müüdud tooted ja teenused 106 Lisa 19. -

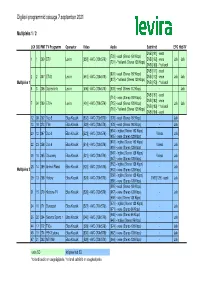

Levira DTT Programmid 09.08.21.Xlsx

Digilevi programmid seisuga 7.september 2021 Multipleks 1 / 2 LCN SID PMT TV Programm Operaator Video Audio Subtiitrid EPG HbbTV DVB [161] - eesti [730] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 1 1 290 ETV Levira [550] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [162] - vene Jah Jah [731] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [163] - *hollandi DVB [171] - eesti [806] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 2 2 307 ETV2 Levira [561] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [172] - vene Jah Jah [807] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) Multipleks 1 DVB [173] - *hollandi 6 3 206 Digilevi info Levira [506] - AVC (720x576i) [603] - eesti (Stereo 112 Kbps) - - Jah DVB [181] - eesti [714] - vene (Stereo 192 Kbps) DVB [182] - vene 7 34 209 ETV+ Levira [401] - AVC (720x576i) [715] - eesti (Stereo 128 Kbps) Jah Jah DVB [183] -* hollandi [716] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [184] - eesti 12 38 202 Duo 5 Elisa Klassik [502] - AVC (720x576i) [605] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah 13 18 273 TV6 Elisa Klassik [529] - AVC (720x576i) [678] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah [654] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 20 12 267 Duo 3 Elisa Klassik [523] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [655] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [618] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 22 23 258 Duo 6 Elisa Klassik [514] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [619] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [646] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 26 10 265 Discovery Elisa Klassik [521] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [647] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [662] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 28 14 269 Animal Planet Elisa Klassik [525] - AVC (720x576i) - Jah Multipleks 2 [663] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [658] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) -

Russian Language Media in Estonia 1990–2012

This is a self-archived version of an original article. This version may differ from the original in pagination and typographic details. Author(s): Jõesaar, Andres; Rannu, Salme; Jufereva, Maria Title: Media for the minorities : Russian language media in Estonia 1990-2012 Year: 2013 Version: Published version Copyright: © Vytauto Didziojo universitetas, 2013 Rights: In Copyright Rights url: http://rightsstatements.org/page/InC/1.0/?language=en Please cite the original version: Jõesaar, A., Rannu, S., & Jufereva, M. (2013). Media for the minorities : Russian language media in Estonia 1990-2012. Media transformations, 9(9), 118-154. https://doi.org/10.7220/2029- 865X.09.07 ISSN 2029-865X 118 doi://10.7220/2029-865X.09.07 MEDIA FOR THE MINORITIES: RUSSIAN LANGUAGE MEDIA IN ESTONIA 1990–2012 Andres JÕESAAR [email protected] PhD, Associate Professor Baltic Film and Media School Tallinn University Head of Media Research Estonian Public Broadcasting Tallinn, Estonia Salme RANNU [email protected] Analyst Estonian Public Broadcasting Tallinn, Estonia Maria JUFEREVA [email protected] PhD Candidate University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä, Finlanda ABSTRACT: This article aims to explore the ways in which Estonian public broa- dcasting tackles one specific media service sphere; how television programmes for language minorities are created in a small country, how economics and European Union media policy have influenced this processes. The article highlights major ten- sions, namely between Estonian and Russian media outlets, Estonian and Russian speakers within Estonia and the EU and Estonia concerning the role of public ser- vice broadcasting (PSB). For research McQuail’s (2010) theoretical framework of media institutions’ influencers – politics, technology and economics – is used. -

Generational Use of News Media in Estonia

Generational Use of News Media in Estonia Contemporary media research highlights the importance of empirically analysing the relationships between media and age; changing user patterns over the life course; and generational experiences within media discourse beyond the widely-hyped buzz terms such as the ‘digital natives’, ‘Google generation’, etc. The Generational Use doctoral thesis seeks to define the ‘repertoires’ of news media that different generations use to obtain topical information and create of News Media their ‘media space’. The thesis contributes to the development of in Estonia a framework within which to analyse generational features in news audiences by putting the main focus on the cultural view of generations. This perspective was first introduced by Karl Mannheim in 1928. Departing from his legacy, generations can be better conceived of as social formations that are built on self- identification, rather than equally distributed cohorts. With the purpose of discussing the emergence of various ‘audiencing’ patterns from the perspectives of age, life course and generational identity, the thesis centres on Estonia – a post-Soviet Baltic state – as an empirical example of a transforming society with a dynamic media landscape that is witnessing the expanding impact of new media and a shift to digitisation, which should have consequences for the process of ‘generationing’. The thesis is based on data from nationally representative cross- section surveys on media use and media attitudes (conducted 2002–2012). In addition to that focus group discussions are used to map similarities and differences between five generation cohorts born 1932–1997 with regard to the access and use of established news media, thematic preferences and spatial orientations of Signe Opermann Signe Opermann media use, and a discursive approach to news formats. -

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List Australia FOX Sport 502 FOX LEAGUE HD Australia FOX Sport 504 FOX FOOTY HD Australia 10 Bold Australia SBS HD Australia SBS Viceland Australia 7 HD Australia 7 TV Australia 7 TWO Australia 7 Flix Australia 7 MATE Australia NITV HD Australia 9 HD Australia TEN HD Australia 9Gem HD Australia 9Go HD Australia 9Life HD Australia Racing TV Australia Sky Racing 1 Australia Sky Racing 2 Australia Fetch TV Australia Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Rugby League 1 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 2 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 3 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 1HD Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 2HD Australia -

Levikomi Telekanalite Põhipaketid Ja Temaatilised Lisapaketid 01.05.2017

levikom.ee 1213 LEVIKOMI TELEKANALITE PÕHIPAKETID JA TEMAATILISED LISAPAKETID 01.05.2017 LEVIKOM RUBIIN (27 KANALIT): Eesti (8): ETV, ETV2, TV3, KANAL 2, Tallinna TV, TV6, ETV HD, ETV2 HD Vene (1): ETV+ Tõsielu (1): National Geographic Lastele (1): Kidzone Muusika (2): MyHits, iConcert Sport (3): Setanta Sports HD, Fuel TV HD, Motors TV HD Filmid ja sarjad (6): Sony Entertainment, Sony Turbo, FOX, FOX Life, Filmzone, Filmzone+ Eesti looduskaamerad (5): Hooajalised Eesti Looduse Veebikaamerad (Hirve, Hülge, Talilinnu, Käsmu ranna, Pesakasti)* Allajoonitud- ja kaldkirjas märgitud kanalid on järele vaadatavad kuni 1 nädal / kokku 10 telekanalit. *Eesti looduskaamerate puhul on Levikom pildi edastaja ning ei vastuta looduskaamerate pildi kvaliteedi või töökindluse eest. Looduskaamerate valik võib hooajaliselt muutuda. LEVIKOM VIASAT HÕBE (42 KANALIT): Eesti (10): ETV, ETV2, TV3, KANAL 2, Tallinna TV, TV6, Kanal 11, Kanal 12, ETV HD, ETV2 HD Vene (5): ETV+, PBK 1, CTC, REN TV Baltic, TV3+ Uudised (4): CNN, BBC World News, Russia Today, NHK World TV Tõsielu (6): National Geographic, National Geographic Wild, Viasat History, Viasat Nature East, Viasat Explorer Lastele (7): Kidzone, Disney Channel, Disney XD, Disney Junior, NickToons, Nickelodeon, Nickelodeon Junior Muusika (3): MTV Hits, VH1, E! Entertainment Euroopa (3): France24, RTL, Sixx Eesti looduskaamerad (5): Hooajalised Eesti Looduse Veebikaamerad (Hirve, Hülge, Talilinnu, Käsmu ranna, Pesakasti)* Allajoonitud- ja kaldkirjas märgitud kanalid on järele vaadatavad kuni 1 nädal / kokku -

Department of Social Research University of Helsinki Finland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Department of Social Research University of Helsinki Finland NORMATIVE STORIES OF THE FORMATIVE MOMENT CONSTRUCTION OF ESTONIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY IN POSTIMEES DURING THE EU ACCESSION PROCESS Sigrid Kaasik-Krogerus ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in lecture room 10, University main building, on 12 February 2016, at 12 noon. Helsinki 2016 Publications of the Faculty of Social Sciences 1 (2016) Media and Communication Studies © Sigrid Kaasik-Krogerus Cover: Riikka Hyypiä & Hanna Sario Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] PL 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto ISSN 2343-273X (Print) ISSN 2343-2748 (Online) ISBN 978-951-51-1047-3 (Paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-1048-0 (PDF) Unigrafia, Helsinki 2016 ABSTRACT This longitudinal research analyzes the construction of Estonian national identity in the country’s largest and oldest daily newspaper Postimees in relation to the European Union (EU) in the course of Estonia’s EU accession process 1997-2003. I combine media studies with political science, EU studies and nationalism studies to scrutinize this period as an example of a ‘formative moment’. During this formative moment the EU became ‘the new official Other’ in relation to which a new temporary community, Estonia as a candidate country, was ‘imagined’ in the paper. The study is based on the assumption that national identity as a normative process of making a distinction between us and Others occurs in societal texts, such as the media. -

Must-Carry Rules, and Access to Free-DTT

Access to TV platforms: must-carry rules, and access to free-DTT European Audiovisual Observatory for the European Commission - DG COMM Deirdre Kevin and Agnes Schneeberger European Audiovisual Observatory December 2015 1 | Page Table of Contents Introduction and context of study 7 Executive Summary 9 1 Must-carry 14 1.1 Universal Services Directive 14 1.2 Platforms referred to in must-carry rules 16 1.3 Must-carry channels and services 19 1.4 Other content access rules 28 1.5 Issues of cost in relation to must-carry 30 2 Digital Terrestrial Television 34 2.1 DTT licensing and obstacles to access 34 2.2 Public service broadcasters MUXs 37 2.3 Must-carry rules and digital terrestrial television 37 2.4 DTT across Europe 38 2.5 Channels on Free DTT services 45 Recent legal developments 50 Country Reports 52 3 AL - ALBANIA 53 3.1 Must-carry rules 53 3.2 Other access rules 54 3.3 DTT networks and platform operators 54 3.4 Summary and conclusion 54 4 AT – AUSTRIA 55 4.1 Must-carry rules 55 4.2 Other access rules 58 4.3 Access to free DTT 59 4.4 Conclusion and summary 60 5 BA – BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 61 5.1 Must-carry rules 61 5.2 Other access rules 62 5.3 DTT development 62 5.4 Summary and conclusion 62 6 BE – BELGIUM 63 6.1 Must-carry rules 63 6.2 Other access rules 70 6.3 Access to free DTT 72 6.4 Conclusion and summary 73 7 BG – BULGARIA 75 2 | Page 7.1 Must-carry rules 75 7.2 Must offer 75 7.3 Access to free DTT 76 7.4 Summary and conclusion 76 8 CH – SWITZERLAND 77 8.1 Must-carry rules 77 8.2 Other access rules 79 8.3 Access to free DTT -

Television Across Europe

media-incovers-0902.qxp 9/3/2005 12:44 PM Page 4 OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE EU MONITORING AND ADVOCACY PROGRAM NETWORK MEDIA PROGRAM ALBANIA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA BULGARIA Television CROATIA across Europe: CZECH REPUBLIC ESTONIA FRANCE regulation, policy GERMANY HUNGARY and independence ITALY LATVIA LITHUANIA Summary POLAND REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA ROMANIA SERBIA SLOVAKIA SLOVENIA TURKEY UNITED KINGDOM Monitoring Reports 2005 Published by OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE Október 6. u. 12. H-1051 Budapest Hungary 400 West 59th Street New York, NY 10019 USA © OSI/EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program, 2005 All rights reserved. TM and Copyright © 2005 Open Society Institute EU MONITORING AND ADVOCACY PROGRAM Október 6. u. 12. H-1051 Budapest Hungary Website <www.eumap.org> ISBN: 1-891385-35-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data. A CIP catalog record for this book is available upon request. Copies of the book can be ordered from the EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program <[email protected]> Printed in Gyoma, Hungary, 2005 Design & Layout by Q.E.D. Publishing TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................ 5 Preface ........................................................................... 9 Foreword ..................................................................... 11 Overview ..................................................................... 13 Albania ............................................................... 185 Bosnia and Herzegovina ...................................... 193