Generational Use of News Media in Estonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minorities and Majorities in Estonia: Problems of Integration at the Threshold of the Eu

MINORITIES AND MAJORITIES IN ESTONIA: PROBLEMS OF INTEGRATION AT THE THRESHOLD OF THE EU FLENSBURG, GERMANY AND AABENRAA DENMARK 22 to 25 MAY 1998 ECMI Report #2 March 1999 Contents Preface 3 The Map of Estonia 4 Ethnic Composition of the Estonian Population as of 1 January 1998 4 Note on Terminology 5 Background 6 The Introduction of the Seminar 10 The Estonian government's integration strategy 11 The role of the educational system 16 The role of the media 19 Politics of integration 22 International standards and decision-making on the EU 28 Final Remarks by the General Rapporteur 32 Appendix 36 List of Participants 37 The Integration of Non-Estonians into Estonian Society 39 Table 1. Ethnic Composition of the Estonian Population 43 Table 2. Estonian Population by Ethnic Origin and Ethnic Language as Mother Tongue and Second Language (according to 1989 census) 44 Table 3. The Education of Teachers of Estonian Language Working in Russian Language Schools of Estonia 47 Table 4 (A;B). Teaching in the Estonian Language of Other Subjects at Russian Language Schools in 1996/97 48 Table 5. Language Used at Home of the First Grade Pupils of the Estonian Language Schools (school year of 1996/97) 51 Table 6. Number of Persons Passing the Language Proficiency Examination Required for Employment, as of 01 August 1997 52 Table 7. Number of Persons Taking the Estonian Language Examination for Citizenship Applicants under the New Citizenship Law (enacted 01 April 1995) as of 01 April 1997 53 2 Preface In 1997, ECMI initiated several series of regional seminars dealing with areas where inter-ethnic tension was a matter of international concern or where ethnopolitical conflicts had broken out. -

Tallinna Linn. Hinnang Liiklusolukorrale Peale Haabersti Liiklussõlme Valmimist

2018 INSENERIBÜROO STRATUM Tallinna linn. Hinnang liiklusolukorrale peale Haabersti liiklussõlme valmimist Täiendatud 30.05.2018 Sisukord 1. Sissejuhatus ja töö lähteülesanne .......................................................................................... 2 2. Liiklusanalüüsi lähteandmed ja eeldused .............................................................................. 2 2.1 Võrdlusandmed eelnevast perioodist .............................................................................. 2 2.2 Liikluse prognoosimudel Tallinn 2018HR ......................................................................... 2 3. Ühistranspordiradade vajaduse hinnang ............................................................................... 3 3.1 Paldiski mnt suund linna. ................................................................................................. 3 3.2 Paldiski mnt suund linnast välja. ...................................................................................... 3 3.3 Rannamõisa tee suund linna. ........................................................................................... 3 3.4 Rannamõisa tee suund linnast välja. ................................................................................ 4 3.5 Ehitajate tee ..................................................................................................................... 4 4. Liikluse analüüs peale Haabersti liiklussõlme valmimist ........................................................ 5 4.1 Mõju - Paldiski mnt.......................................................................................................... -

Kristiine Prisma on Tänasest Oma Alkoholimüügi Loast Ilma. Keeld

USD SEK Euribor ÄP indeks 0,11% 11,08 EEK 1,70 EEK 4,750 2508,59 Tallinkist Euroopa suurim firma Tallink Grupi üks omanik Enn Pant unistab, et Tallink oleks hiljemalt kümne aasta pä- rast reisijateveo sektoris suurim laevafir- ma Euroopas. Kruiisilaevanduse turule Tal- linkil Pandi hinnangul niipea veel siiski asja WORLD'S BEST-DESIGNED NEWSPAPER MAAILMA PARIMA KUJUNDUSEGA AJALEHT ei ole. 2 | | Neljapäev, 27. september 2007 | nr 175 (3426) | 19 kr | ARVAMUS Pooled veeprojektid on takerdu- nud, sest vahepealne hinnaralli on tõstnud nen- de maksu- muse kohati kolmekord- seks. Jaanus Tamkivi, keskkonnaminister 27 BÖRS 0,7% II pensionisamba Eile lõuna ajal seati Tallinnas Kristiine Prismas üles silte, mis teavitavad kliente tänasest kehtima hakkavast alkoholimüügi keelust. Foto: Andres Haabu rahast on paiguta- tud Eesti aktsia- tesse. Pensionifon- did ei pea Tallinna börsi atraktiivseks. 10–11 LISAKS TEHNIKA 16 Lotus Symphony versus OpenOffice Tehtud! ÄRIPÄEV IDA- VIRUMAAL 20 Maakonna Kristiine Prisma on tänasest edukaim oli Viru Keemia Grupp oma alkoholimüügi loast LISAKS TSITAAT Suurim töökuulutuste leht Eestis: tiraaž 100 000, levib üle Eesti TÖÖKUULUTUSED | Neljapäev, 27. september 2007 | nr 39 (133) | tasuta | kor o Mik o : Arn: ilma. Keeld kangema Kaua me võime taluda seda, mis Foto Evert Kreek julgeb teha toimub alkoholi tarbimisega. See on asju valesti DHL Eesti tegevjuht teab, et tänapäeva äris, kus aeg on raha ja kiirus loeb, on parem teha hea kraamiga kaubelda kehtib ületanud igasugused piirid. Miks siis seda otsus täna kui väga hea homme. 3 TOOTMISE PLANEERIJAT VAHETUSE VANEMAT kelle põhiülesanneteks on toodangu õigeaegseks kelle põhiülesanneteks on vahetuse töö korraldamine sh AS Favor on 1990. -

Elisa Elamus Kaabliga Kanalipaketid Kanalid Seisuga 01.07.2021

Elisa Elamus kaabliga kanalipaketid kanalid seisuga 01.07.2021 XL-pakett L-pakett M-pakett S-pakett KANALI NIMI KANALI NR AUDIO SUBTIITRID KANALI NIMI KANALI NR AUDIO SUBTIITRID ETV HD 1 EST PBK 60 RUS Kanal 2 HD 2 EST RTR-Planeta 61 RUS TV3 HD 3 EST REN TV 62 RUS ETV2 HD 4 EST NTV Mir 63 RUS TV6 HD 5 EST 3+ HD 66 RUS Kanal 11 HD 6 EST STS 71 RUS Kanal 12 HD 7 EST Dom kino 87 RUS Elisa 14 EST TNT4 90 RUS Cartoon Network 17 ENG; RUS TNT 93 RUS KidZone TV 20 EST; RUS Pjatnitsa 104 RUS Euronews HD 21 ENG Kinokomedia HD 126 RUS CNBC Europe 32 ENG Eesti kanal 150 EST Alo TV 46 EST Meeleolukanal HD 300 EST MyHits HD 47 EST Euronews 704 RUS Deutche Welle 56 ENG Duo 7 HD 934 RUS ETV+ 59 ENG Fox Life 8 ENG; RUS EST Viasat History HD 33 ENG; RUS EST; FIN Fox 9 ENG; RUS EST History 35 ENG; RUS EST Duo 3 HD 10 ENG; RUS EST Discovery Channel 37 ENG; RUS EST TLC 15 ENG; RUS EST BBC Earth HD 44 ENG Nickelodeon 18 ENG; EST; RUS VH1 48 ENG CNN 22 ENG TV7 57 EST BBC World News 23 ENG Orsent TV 69 RUS Bloomberg TV 24 TVN 70 RUS Eurosport 1 HD 28 ENG; RUS 1+2 72 RUS Duo 6 HD 11 ENG; RUS Mezzo 45 FRA FilmZone HD 12 ENG; RUS EST MCM Top HD 49 FRA FilmZone+ HD 13 ENG; RUS EST Trace Urban HD 50 ENG AMC 16 ENG; RUS MTV Europe 51 ENG Pingviniukas 19 EST; RUS Eurochannel HD 52 RUS HGTV HD 27 ENG EST Life TV 58 RUS Eurosport 2 HD 29 ENG; RUS TV XXI 67 RUS Setanta Sports 1 31 ENG; RUS Kanal Ju 73 RUS Viasat Explore HD 34 ENG; RUS EST; FIN 24 Kanal 74 UKR National Geographic 36 ENG; RUS EST Belarus 24 HD 75 RUS Animal Planet HD 38 ENG; RUS KidZone+ HD 503 EST; RUS Travel Chnnel HD 39 ENG; RUS SmartZone HD 508 EST; RUS Food Network HD 40 ENG; RUS Fight Sports HD 916 ENG Investigation Discovery HD 41 ENG; RUS EST VIP Comedy HD 921 ENG; RUS EST CBS Reality 42 ENG; RUS Epic Drama HD 922 ENG; RUS EST National Geographic HD 900 ENG; RUS Arte HD 908 FRA; GER Nat Geo Wild HD 901 ENG; RUS Mezzo Live HD 909 FRA History HD 904 ENG FIN Stingeray iConcerts HD 910 FRA Setanta Sports 1 HD 907 ENG; RUS. -

A4 8Lk Veskimetsa-Mustjõe Selts Infokiri 2020

VVEESSKKIIMMEETTSSAA--MMUUSSTTJJÕÕEE SSEELLTTSS 2 0 2 0 | I N F O K I R I N R 4 TEIE KÄES ON VESKIMETSA-MUSTJÕE SELTSI JÄRJEKORDNE INFOKIRI, MILLEGA TOOME ASUMI ELANIKENI INFOT SELTSI TEGEMISTEST JA UUDISEID ASUMIS TOIMUVA KOHTA 2020. aasta juunis täitus Veskimetsa-Mustjõe Seltsil neli aastat aktiivset tegutsemist. Hea meel on tõdeda, et selts on endiselt tegus ja seltsi kuuluvad aktiivseid liikmeid, kellel on entusiasmi ja motivatsiooni asumis kogukonda kokku tuua ja seista meie naabruskonna elukeskkonna eest. Seltsi esindajad on aktiivselt suhelnud ametkondade ja linnavalitsusega asumi heakorra ja liiklusohutuse teemadel. Veskimetsa-Mustjõe Selts, nagu palju teisedki asumiseltsid, on kujunenud Tallinna linnaplaneerimisel ja juhtimise usaldusväärseks partneriks, kelle arvamust küsitakse ning kel on võimalus edastada kohalikke muresid, ootusi ja ettepanekuid ametkondadesse. Veskimetsa-Mustjõe Selts on korraldanud alates 2016. aastast kogukonnale suunatud ühisüritusi, millest on saanud juba traditsioon: Talvekohvikupäev, "Teeme ära" talgud, Puhvetipäev ja Külapäev. Käesolev aasta on olnud igatepidi eriline ja teistmoodi. Kuna sel aastal jäi talv ära, ilmaolud olid kesised ja ettearvamatud, siis olime sunnitud talvekohvikupäevast sel aastal loobuma. Ootasime talgupäeva, ent viirusega seotud kriisiperiood tegi plaanidesse muudatuse. Traditsiooniliselt juuni lõpus toimuv Puhvetipäev oli välja kuulutatud, ent kuna oli teadmata, millised on selle hetke võimalused rahvarohket üritust korraldada, võttis selts vastu otsuse Puhvetipäev korraldada -

The Health Profile of Tallinn

THE HEALTH PROFILE OF TALLINN THE HEALTH PROFILE OF TALLINN Positive developments, problem areas and intervention needs in the health of the population of Tallinn at the end of the first decade of the 21st century Tallinn Social Welfare and Health Care Department Tallinn 2010 This document is a short summary of the Health Profile of Tallinn (http://www.tallinn.ee/ g4181s51124), analysing the changes in the health of the city’s population and temporal trends in factors affecting health, presenting positive changes and tight spots in the health situation of the city people. The Health Profile of Tallinn will be the basis for defining targets for the future health promotion and for setting up necessary interventions in health promotion in the city. DEMOGRAPHIC AND GENERAL MORBIDITY RATE DATA The area of Tallinn is 158.27 km² and the population density is slowly but consistently growing (Figure 1). In 2008, the population density was 2512.27 people per km2 and in 2009, 2518.40 people per km2. In the last few years, the net migration balance has remained stable. Tallinna rahvastik Paljasaare laht PIRITA Tallinna laht Kakumäe laht PÕHJA- Kopli laht TALLINN LASNAMÄE HAABERSTI KESKLINN Harku KRISTIINE järv MUSTAMÄE Ülemiste järv Asustustihedus 1 - 500 NÕMME 501 - 1 500 1 501 - 3 000 3 001 - 6 000 Allikas - Rahvastikuregister Figure 1 Population density in Tallinn, ppl./ km² 4 Source: Population Register 3,00 2,00 1,00 0,00 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 -1,00 Tallinn Ees ti -2,00 -3,00 -4,00 -5,00 Statistikaamet Birth rate in Tallinn has increased (Figure 2) more than in Estonia as a whole and natural popula- tion increase has been positive since 2006 (Figure 3). -

ANNEXE 3. Tableaux

ANNEXE 3. Tableaux Tableau 1. Durée d’écoute moyenne par individu (2003) Classement par durée Durée d’écoute moyenne par adulte, Lundi-Dimanche (minutes par jour) Serbie et Monténégro 278 Hongrie 274 Macédoine 259 Croatie 254 Pologne 250 Italie 245 Estonie 239 Royaum-Uni 239 Slovaquie 235 Roumanie 235 Turquie 224 Allemagne 217 République tchèque 214 France 213 Lituanie 210 Lettonie 207 Bulgarie 185 Slovénie 178 Albanie NA Bosnie Herzégovine NA Moyenne (18 pays) 219 Source: Comité International de marketing, IP176 EU MONITORING AND ADVOCACY PROGRAM ( EUMAP) – RAPPORT GÉNÉRAL 139 NETWORK MEDIA PROGRAM ( NMP) Tableau 2. L’équipement des ménages Classé par population Ménages équipés de télévision (MET) (avec au moins un poste de télévision) Nombre de chaînes Population Ménages Part du total des terrestres reçues par 70% (milliers) (milliers) Total ménages de la population (milliers) (%) Allemagne 82,537 38,720 34,370177 91.1 25 Turquie 71,271 16,460 10,789 97.9 15 France 61,684 24,870 23,750 95.0178 7 Royaume-Uni 59,232 25,043 24,482 97.8 5 Italie 55,696 21,645 21,320 98.5 9 Pologne 38,195 13,337 12,982 97.3 6 Roumanie179 21,698 7,392 6,763 91.5 3 République tchèque 10,230 3,738 3,735 97.6 4 Hongrie 10,117 3,863 3,785 98.0 3 Serbie et Monténégro180 8,120 2,700 2,300181 98.0 6 Bulgarie 7,845 2,905 2,754 94.8 2 Slovaquie 5,379 1,645 1,628 99.0 4 Croatie 4,438 1,477 1,448 97.5 4 Bosnie Herzégovine182 3,832 NA NA 97.0 6 Lituanie 3,463 1,357 1,331 98.1 4 Albanie183 3,144 726 500 68.8 1 Lettonie 2,331 803 780 97.2 4 Macédoine 2,023 564 467 83.0 7 Slovénie 1,964 685 673 98.0 5 Estonie 1,356 582 565 97.1 3 Source: Comité international de Marketing IP,184 Rapports nationaux EUMAP; Recherche EUMAP EU MONITORING AND ADVOCACY PROGRAM ( EUMAP) – RAPPORT GÉNÉRAL 140 NETWORK MEDIA PROGRAM ( NMP) Tableau 3. -

Levi TV Kanalid

levikom.ee 1213 Paksenduse (bold) ja punase teksti tähistusega telekanaleid on võimalik järelvaadata 7 päeva täies mahus (järelvaatamise teenus on eraldi kuutasu eest)! Telekanalite Levi TV Paras Levi TV Priima Levi TV Ekstra sisaldumine pakettides: - Põhikanaleid 33 kanalit 63 kanalit 69 kanalit - Muid kanaleid 5 kanalit 5 kanalit 10 kanalit KÕIK KOKKU: 38 telekanalit 68 telekanalit 79 telekanalit Eesti telekanalid: ETV ✓ ✓ ✓ ETV2 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 2 ✓ ✓ ✓ TV3 ✓ ✓ ✓ TV6 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 11 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 12 ✓ ✓ ✓ Alo TV ✓ ✓ ✓ Taevas TV7 ✓ ✓ ✓ Eesti Kanal ✓ ✓ ✓ Eesti Kanal Pluss ✓ ✓ ✓ (11 kanalit) (11 kanalit) (11 kanalit) Eesti kanalid HD formaadis (duplikaadina): ETV HD ✓ ✓ ✓ ETV2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 11 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 12 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ TV3 HD ✓ TV6 HD ✓ (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) Laste ja noorte telekanalid: Kidzone ✓ ✓ ✓ Kidzone+ HD ✓ ✓ Smartzone HD ✓ ✓ KiKa HD ✓ ✓ Nick JR ✓ ✓ Nickelodeon ✓ ✓ TEL 1213 TEL +372 684 0678 Levikom Eesti OÜ Pärnu mnt 139C, 11317 Tallinn [email protected] | levikom.ee Pingviniukas ✓ ✓ ✓ Multimania ✓ ✓ ✓ Mamontjonok ✓ ✓ ✓ (4 kanalit) (9 kanalit) (9 kanalit) Filmide ja sarjade telekanalid: Epic Drama HD ✓ ✓ ✓ TLC ✓ ✓ ✓ Sony Channel HD ✓ ✓ Sony Turbo HD ✓ ✓ FOX ✓ ✓ FOX Life ✓ ✓ Filmzone ✓ ✓ Filmzone+ HD ✓ ✓ Kino 24 ✓ ✓ ✓ Pro100TV ✓ ✓ ✓ Dom Kino ✓ ✓ ✓ (5 kanalit) (9 kanalit) (11 kanalit) Sporditeemalised telekanalid: Eurosport 1 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Eurosport 2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Setanta Sports HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Fuel TV HD ✓ ✓ Nautical Channel ✓ ✓ (3 kanalit) (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) Teaduse, looduse ja tõsielu teemalised telekanalid: Discovery -

Digital Divide in Estonia and How to Bridge It

Digital Divide In Estonia and How to Bridge It Editors: Mari Kalkun (Emor) Tarmo Kalvet (PRAXIS) Emor and PRAXIS Center for Policy Studies Tallinn 2002 Digital Divide In Estonia and How to Bridge It Editors: Mari Kalkun (Emor) Tarmo Kalvet (PRAXIS) Tallinn 2002 This report was prepared at the order, with funding from and in direct partnership with the Look@World Foundation, the Open Estonia Foundation, and the State Chancellery. Co-financers: The study was co-financed (partial research, pdf-publications, PRAXIS’ Policy Analysis Publications, distribution) by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) for the Information for Development Program (infoDev) by a grant to the PRAXIS Center for Policy Studies for ICT Infrastructure and E-Readiness Assessment (Grant # ICT 016). The translation into Russian and English, and publication of the web-version was supported by the Open Society Institute – Budapest. Contractors: © Emor (Chapters III, V, VI, VII; Annexes 2, 3, 4) Ahtri 12, 10151 Tallinn Tel. (372) 6 268 500; www.emor.ee © PRAXIS Center for Policy Studies (Chapters II, IV, VIII) Estonia Ave. 3/5, 10143 Tallinn Tel. (372) 6 409 072; www.praxis.ee © Emor and PRAXIS Center for Policy Studies (Executive Summary, Chapter I) Materials in the current report are subject to unlimited and free use if references to the authors and financers are provided. ISBN: 9985-78-736-6 Layout: Helena Nagel Contents 4 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Mari Kalkun, Tarmo Kalvet, Daimar Liiv, Ülle Pärnoja . 6 1. Objectives of study . 6 2. “Blue collar” individuals and “passive people” are distinguished among non-users of the Internet . -

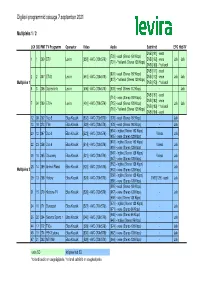

Levira DTT Programmid 09.08.21.Xlsx

Digilevi programmid seisuga 7.september 2021 Multipleks 1 / 2 LCN SID PMT TV Programm Operaator Video Audio Subtiitrid EPG HbbTV DVB [161] - eesti [730] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 1 1 290 ETV Levira [550] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [162] - vene Jah Jah [731] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [163] - *hollandi DVB [171] - eesti [806] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 2 2 307 ETV2 Levira [561] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [172] - vene Jah Jah [807] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) Multipleks 1 DVB [173] - *hollandi 6 3 206 Digilevi info Levira [506] - AVC (720x576i) [603] - eesti (Stereo 112 Kbps) - - Jah DVB [181] - eesti [714] - vene (Stereo 192 Kbps) DVB [182] - vene 7 34 209 ETV+ Levira [401] - AVC (720x576i) [715] - eesti (Stereo 128 Kbps) Jah Jah DVB [183] -* hollandi [716] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [184] - eesti 12 38 202 Duo 5 Elisa Klassik [502] - AVC (720x576i) [605] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah 13 18 273 TV6 Elisa Klassik [529] - AVC (720x576i) [678] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah [654] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 20 12 267 Duo 3 Elisa Klassik [523] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [655] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [618] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 22 23 258 Duo 6 Elisa Klassik [514] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [619] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [646] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 26 10 265 Discovery Elisa Klassik [521] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [647] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [662] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 28 14 269 Animal Planet Elisa Klassik [525] - AVC (720x576i) - Jah Multipleks 2 [663] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [658] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) -

No Monitoring Obligations’ the Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ a Story of Untameable Monsters by Giancarlo F

The Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ The Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ A Story of Untameable Monsters by Giancarlo F. Frosio* Abstract: In imposing a strict liability regime pean Commission, would like to introduce filtering for alleged copyright infringement occurring on You- obligations for intermediaries in both copyright and Tube, Justice Salomão of the Brazilian Superior Tribu- AVMS legislations. Meanwhile, online platforms have nal de Justiça stated that “if Google created an ‘un- already set up miscellaneous filtering schemes on a tameable monster,’ it should be the only one charged voluntary basis. In this paper, I suggest that we are with any disastrous consequences generated by the witnessing the death of “no monitoring obligations,” lack of control of the users of its websites.” In order a well-marked trend in intermediary liability policy to tame the monster, the Brazilian Superior Court that can be contextualized within the emergence of had to impose monitoring obligations on Youtube; a broader move towards private enforcement online this was not an isolated case. Proactive monitoring and intermediaries’ self-intervention. In addition, fil- and filtering found their way into the legal system as tering and monitoring will be dealt almost exclusively a privileged enforcement strategy through legisla- through automatic infringement assessment sys- tion, judicial decisions, and private ordering. In multi- tems. Due process and fundamental guarantees get ple jurisdictions, recent case law has imposed proac- mauled by algorithmic enforcement, which might fi- tive monitoring obligations on intermediaries across nally slay “no monitoring obligations” and fundamen- the entire spectrum of intermediary liability subject tal rights online, together with the untameable mon- matters. -

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government Historical Culture, Conflicting Memories and Identities in post-Soviet Estonia Meike Wulf Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of London London 2005 UMI Number: U213073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U213073 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ih c s e s . r. 3 5 o ^ . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract This study investigates the interplay of collective memories and national identity in Estonia, and uses life story interviews with members of the intellectual elite as the primary source. I view collective memory not as a monolithic homogenous unit, but as subdivided into various group memories that can be conflicting. The conflict line between ‘Estonian victims’ and ‘Russian perpetrators* figures prominently in the historical culture of post-Soviet Estonia. However, by setting an ethnic Estonian memory against a ‘Soviet Russian’ memory, the official historical narrative fails to account for the complexity of the various counter-histories and newly emerging identities activated in times of socio-political ‘transition’.