Optimization of Microbial Cell Factories with Systems Biology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ATP-Citrate Lyase Has an Essential Role in Cytosolic Acetyl-Coa Production in Arabidopsis Beth Leann Fatland Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2002 ATP-citrate lyase has an essential role in cytosolic acetyl-CoA production in Arabidopsis Beth LeAnn Fatland Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Molecular Biology Commons, and the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Fatland, Beth LeAnn, "ATP-citrate lyase has an essential role in cytosolic acetyl-CoA production in Arabidopsis " (2002). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1218. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1218 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ATP-citrate lyase has an essential role in cytosolic acetyl-CoA production in Arabidopsis by Beth LeAnn Fatland A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Plant Physiology Program of Study Committee: Eve Syrkin Wurtele (Major Professor) James Colbert Harry Homer Basil Nikolau Martin Spalding Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2002 UMI Number: 3158393 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

When the Reaction Is

Table S3. iJL1678-ME model modification (blocked reactions) Iter. Cat. ID Name Formula Subsystem Comments (When the reaction is turned on) 1 bp2 EDD 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase 6pgc_c⇌2ddg6p_c + h2o_c Pentose Phosphate Pathway Create a major effect of steep acetate overflow elevation in high growth. Comparing to the main glycolytic pathway, it is metabolicly less efficient but proteomicly more efficient. bp1 ICL Isocitrate lyase icit_c→glx_c + succ_c Anaplerotic Reactions Bypass for the main TCA cycle pathways from turning isocitrate to succinate, when ICL is turned on, Isocitrate dehydrogenase(ICDHyr), 2-Oxogluterate dehydrogenase(AKGDH) and Succinyl-CoA synthetase (ATP-forming,SUCOAS) would reduce. Ref. (1) and (2) shows that this reaction is off in higher growth. Ref. (3) shows that this reaction is converging to being off when the dynamic of respiration using enzyme kinetics is simulated. 2 bp1 ABTA 4-aminobutyrate transaminase 4abut_c + akg_c⇌glu__L_c + sucsal_c Arginine and Proline Metabolism Another backup pathway of succinate production, from 2-Oxoglutarate (akg). Respiration would be induced when it is on, since the flux through ETC(CYTBO3_4pp and ATPS4rpp) would increase. As it requires the co-factor pyridoxal 5'-phosphate(2−) to get catalyzed(4), indicating that this reaction is regulated by the flux of other reactions(pyridoxal 5'- phosphate(2-) production, etc.). 3 GLYAT Glycine C-acetyltransferase accoa_c + gly_c⇌2aobut_c + coa_c Glycine and Serine Metabolism A reaction that back up for the respiration. Reactions fluxes in TCA cycle would drop when this reaction is turned on. It also requires pyridoxal 5'-phosphate(2−) for the regulation. 4 NADTRHD NAD transhydrogenase nad_c + nadph_c⇌nadh_c + nadp_c Oxidative Phosphorylation A reaction that would make the transition between NAD and NADP metabolically more efficient. -

The Human Flavoproteome

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 535 (2013) 150–162 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yabbi Review The human flavoproteome ⇑ Wolf-Dieter Lienhart, Venugopal Gudipati, Peter Macheroux Graz University of Technology, Institute of Biochemistry, Petersgasse 12, A-8010 Graz, Austria article info abstract Article history: Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) is an essential dietary compound used for the enzymatic biosynthesis of FMN and Received 17 December 2012 FAD. The human genome contains 90 genes encoding for flavin-dependent proteins, six for riboflavin and in revised form 21 February 2013 uptake and transformation into the active coenzymes FMN and FAD as well as two for the reduction to Available online 15 March 2013 the dihydroflavin form. Flavoproteins utilize either FMN (16%) or FAD (84%) while five human flavoen- zymes have a requirement for both FMN and FAD. The majority of flavin-dependent enzymes catalyze Keywords: oxidation–reduction processes in primary metabolic pathways such as the citric acid cycle, b-oxidation Coenzyme A and degradation of amino acids. Ten flavoproteins occur as isozymes and assume special functions in Coenzyme Q the human organism. Two thirds of flavin-dependent proteins are associated with disorders caused by Folate Heme allelic variants affecting protein function. Flavin-dependent proteins also play an important role in the Pyridoxal 50-phosphate biosynthesis of other essential cofactors and hormones such as coenzyme A, coenzyme Q, heme, pyri- Steroids doxal 50-phosphate, steroids and thyroxine. Moreover, they are important for the regulation of folate Thyroxine metabolites by using tetrahydrofolate as cosubstrate in choline degradation, reduction of N-5.10-meth- Vitamins ylenetetrahydrofolate to N-5-methyltetrahydrofolate and maintenance of the catalytically competent form of methionine synthase. -

Structural Basis for Human Sterol Isomerase in Cholesterol Biosynthesis and Multidrug Recognition

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10279-w OPEN Structural basis for human sterol isomerase in cholesterol biosynthesis and multidrug recognition Tao Long 1, Abdirahman Hassan 1, Bonne M Thompson2, Jeffrey G McDonald1,2, Jiawei Wang3 & Xiaochun Li 1,4 3-β-hydroxysteroid-Δ8, Δ7-isomerase, known as Emopamil-Binding Protein (EBP), is an endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein involved in cholesterol biosynthesis, autophagy, 1234567890():,; oligodendrocyte formation. The mutation on EBP can cause Conradi-Hunermann syndrome, an inborn error. Interestingly, EBP binds an abundance of structurally diverse pharmacolo- gically active compounds, causing drug resistance. Here, we report two crystal structures of human EBP, one in complex with the anti-breast cancer drug tamoxifen and the other in complex with the cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitor U18666A. EBP adopts an unreported fold involving five transmembrane-helices (TMs) that creates a membrane cavity presenting a pharmacological binding site that accommodates multiple different ligands. The compounds exploit their positively-charged amine group to mimic the carbocationic sterol intermediate. Mutagenesis studies on specific residues abolish the isomerase activity and decrease the multidrug binding capacity. This work reveals the catalytic mechanism of EBP-mediated isomerization in cholesterol biosynthesis and how this protein may act as a multi-drug binder. 1 Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA. 2 Center for Human Nutrition, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA. 3 State Key Laboratory of Membrane Biology, School of Life Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China. 4 Department of Biophysics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0137846A1 ATSUMI Et Al

US 2017.0137846A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0137846A1 ATSUMI et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 18, 2017 (54) BACTERIA ENGINEERED FOR Related U.S. Application Data CONVERSION OF ETHYLENE TO (60) Provisional application No. 62/009,857, filed on Jun. N-BUTANOL 9, 2014. (71) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Oakland, CA (US) Publication Classification (51) Int. Cl. (72) Inventors: Shota ATSUMI, Davis, CA (US); CI2P 7/06 (2006.01) Michael D. TONEY, Davis, CA (US); CI2P 7/16 (2006.01) Gabriel M. RODRIGUEZ, Davis, CA CI2N 15/52 (2006.01) (US); Yohei TASHIRO, Davis, CA (52) U.S. Cl. (US); Justin B. SIEGEL, Davis, CA CPC ................ CI2P 7/06 (2013.01): CI2N 15/52 (US); D. Alexander CARLIN, Davis, (2013.01); C12Y402/01053 (2013.01); C12Y CA (US); Irina KORYAKINA, Davis, 402/01095 (2013.01); C12Y 114/13 (2013.01); CA (US); Shuchi H. DESAI, Davis, CI2Y 102/01002 (2013.01); C12Y 114/13069 CA (US) (2013.01); C12Y 203/01009 (2013.01); C12Y 101/01157 (2013.01); C12Y402/01 (2013.01); (73) Assignee: The Regents of the University of CI2Y 103/01038 (2013.01); C12Y 102/01003 California, Oakland, CA (US) (2013.01); C12P 7/16 (2013.01) (21) Appl. No.: 15/317,656 (57) ABSTRACT (22) PCT Fed: Jun. 9, 2015 The present disclosure provides recombinant bacteria with elevated production of ethanol and/or n-butanol from eth (86) PCT No.: PCT/US 15/34942 ylene. Methods for the production of the recombinant bac S 371 (c)(1), teria, as well as for use thereof for production of ethanol (2) Date: Dec. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,906,307 B2 S0e Et Al

US007906307B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,906,307 B2 S0e et al. (45) Date of Patent: Mar. 15, 2011 (54) VARIANT LIPIDACYLTRANSFERASES AND 4,683.202 A 7, 1987 Mullis METHODS OF MAKING 4,689,297 A 8, 1987 Good 4,707,291 A 11, 1987 Thom 4,707,364 A 11/1987 Barach (75) Inventors: Jorn Borch Soe, Tilst (DK); Jorn 4,708,876 A 1 1/1987 Yokoyama Dalgaard Mikkelson, Hvidovre (DK); 4,798,793 A 1/1989 Eigtved 4,808,417 A 2f1989 Masuda Arno de Kreij. Geneve (CH) 4,810,414 A 3/1989 Huge-Jensen 4,814,331 A 3, 1989 Kerkenaar (73) Assignee: Danisco A/S, Copenhagen (DK) 4,818,695 A 4/1989 Eigtved 4,826,767 A 5/1989 Hansen 4,865,866 A 9, 1989 Moore (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 4,904.483. A 2f1990 Christensen patent is extended or adjusted under 35 4,916,064 A 4, 1990 Derez U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 5,112,624 A 5/1992 Johna 5,213,968 A 5, 1993 Castle 5,219,733 A 6/1993 Myojo (21) Appl. No.: 11/852,274 5,219,744 A 6/1993 Kurashige 5,232,846 A 8, 1993 Takeda (22) Filed: Sep. 7, 2007 5,264,367 A 11/1993 Aalrust (Continued) (65) Prior Publication Data US 2008/OO70287 A1 Mar. 20, 2008 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS AR 331094 2, 1995 Related U.S. Application Data (Continued) (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. -

A Squalene–Hopene Cyclase in Schizosaccharomyces Japonicus Represents a Eukaryotic Adaptation to Sterol-Limited Anaerobic Environments

A squalene–hopene cyclase in Schizosaccharomyces japonicus represents a eukaryotic adaptation to sterol-limited anaerobic environments Jonna Bouwknegta,1, Sanne J. Wiersmaa,1, Raúl A. Ortiz-Merinoa, Eline S. R. Doornenbala, Petrik Buitenhuisa, Martin Gierab, Christoph Müllerc, and Jack T. Pronka,2 aDepartment of Biotechnology, Delft University of Technology, 2629 HZ Delft, The Netherlands; bCenter for Proteomics and Metabolomics, Leiden University Medical Center, 2333 ZA Leiden, The Netherlands; and cDepartment of Pharmacy, Center for Drug Research, Ludwig-Maximillians University Munich, 81377 Munich, Germany Edited by Roger Summons, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, and approved July 6, 2021 (received for review March 18, 2021) Biosynthesis of sterols, which are key constituents of canonical and acquisition of a bacterial STC gene by horizontal gene transfer is eukaryotic membranes, requires molecular oxygen. Anaerobic protists considered a key evolutionary adaptation of Neocalllimastigomycetes and deep-branching anaerobic fungi are the only eukaryotes in which to the strictly anaerobic conditions of the gut of large herbivores a mechanism for sterol-independent growth has been elucidated. In (7). The reaction catalyzed by STC resembles oxygen-independent these organisms, tetrahymanol, formed through oxygen-independent conversion of squalene to hopanol and/or other hopanoids by cyclization of squalene by a squalene–tetrahymanol cyclase, acts as a squalene–hopene cyclases (8) (SHC; SI Appendix,Fig.S1), which sterol surrogate. This study confirms an early report [C. J. E. A. Bulder, are found in many bacteria (9, 10). Some bacteria synthesize tet- Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek,37,353–358 (1971)] that Schizosaccharo- rahymanol by ring expansion of hopanol, in a reaction catalyzed by myces japonicus is exceptional among yeasts in growing anaerobi- tetrahymanol synthase (THS) for which the precise mechanism cally on synthetic media lacking sterols and unsaturated fatty acids. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,642,021 B2 Brautigam Et Al

USOO8642021B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,642,021 B2 Brautigam et al. (45) Date of Patent: *Feb. 4, 2014 (54) CONDITIONING COMPOSITION FOR HAIR FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (75) Inventors: Ina Brautigam, Darmstadt (DE); Frank DE 2630560 1/1978 ............... A61K 7.48 EP O315541 5, 1989 ............... A61K 7.48 Hermes, Seeheim (DE) FR 241 1001 7, 1979 ............... A61K 700 JP O7327633. A * 12/1995 (73) Assignee: Kao Germany GmbH, Darmstadt (DE) WO WOOO28966 A1 * 5, 2000 WO WOO3,070208 A1 8/2003 ............. A61K 7,134 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 OTHER PUBLICATIONS U.S.C. 154(b) by 1520 days. Abstract Accession No. 2000:35.1345 from the CaPlus database on This patent is Subject to a terminal dis STN, the bibliography, abstract and indexing data for WO 200028966 claimer. A1, downloaded on Aug. 8, 2007, 2 pages.* Quest International: “Yogurtene” Cosmetic Ingredients (Jun. 2000) (21) Appl. No.: 11/001,840 pp. 1-17.* Machine translation of JP 07327633A dowloaded from the JPO Feb. (22) Filed: Dec. 2, 2004 14, 2012.* thehealthyeating.org website (www.healthyeating.org/Milk-Dairy/ (65) Prior Publication Data Nutrients-in-Milk-Cheese-Yogurt/Yogurt-Nutrition. aspx?Referer-dairycouncilofca (downloaded Feb. 28, 2013).* US 2005/O152863 A1 Jul. 14, 2005 Website: Clairol's Touch of Yoghurt Shampoo (http://brandfailures. (30) Foreign Application Priority Data blogspot.com/2006/12/other-famous-brand-idea-failures.html) downloaded Feb. 28, 2013).* Skin Deep website http://www.ewg.org/skindeepfingredient/ Dec. 5, 2003 (EP) ..................................... O3O27985 702759/GUAR HYDROXYPROPYLTRIMONIUM CHLO RIDE/downloaded Sep. -

(12)UK Patent Application (1S1GB ,„>2577037 ,,3,A 2577037

(12)UK Patent Application (1S1GB ,„>2577037 ,,3,A (43) Date of A Publication 18.03.2020 (21) Application No: 1812997.3 (51) INT CL: C12N 15/52 (2006.01) C12P 33/02 (2006.01) (22) Date of Filing: 09.08.2018 C12R 1/32 (2006.01) C12R 1/365 (2006.01) (56) Documents Cited: GB 2102429 A EP 3112472 A (71) Applicant(s): WO 2001/031050 A US 4345029 A Cambrex Karlskoga AB US 4320195 A (Incorporated in Sweden) Appl Environ Microbiol, published online 4 May 2018, S-691 85 Karlskoga, Sweden Liu et al, "Characterization and engineering of 3- ketosteroid 9a-hydroxylases in Mycobacterium Rijksuniversiteit Groningen neoarum ATCC 25795 for the development of (Incorporated in the Netherlands) androst-1,4- diene3,17-dione and 9a-hydroxy- Broerstraat 5, 9712 CP Groningen, Netherlands androst-4-ene-3,17-dione-producing strains" Appl Environ Microbiol, Vol 77 (2011), Wilbrink et al, (72) Inventor(s): "FadD19 of Rhodococcus rhodochrous DMS43269, a Jonathan Knight steroid-coenzyme A ligase essential for degradation Cecilia Kvarnstrom Branneby of C-24 branched sterol side chains", pp 4455-4464 Lubbert Dijkhuizen FEMS Microbiol Letts, Vol 205 (2001), van der Geize et Janet Maria Petrusma al, "Unmarked gene deletion mutagenesis of kstD, Laura Fernandez De Las Heras encoding 3-ketosteroid deltal-dehydrogenase, in Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 using sacB as a counter-selectable marker", pp 197-202 (74) Agent and/or Address for Service: J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, Vol 172 (2017), Guevara Potter Clarkson LLP et al, "Functional characterization of 3-ketosteroid 9a- The -

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

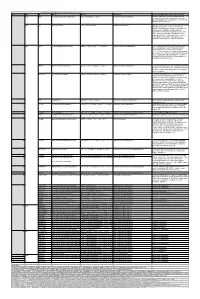

Authors: Zheng Zhao, Delft University of Technology Marcel A. van den Broek, Delft University of Technology S. Aljoscha Wahl, Delft University of Technology Wilbert H. Heijne, DSM Biotechnology Center Roel A. Bovenberg, DSM Biotechnology Center Joseph J. Heijnen, Delft University of Technology An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Marco A. van den Berg, DSM Biotechnology Center Peter J.T. Verheijen, Delft University of Technology Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. PchrCyc: Penicillium rubens Wisconsin 54-1255 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. Liang Wu, DSM Biotechnology Center Walter M. van Gulik, Delft University of Technology L-quinate phosphate a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar multidrug multidrug a dicarboxylate phosphate a proteinogenic 2+ 2+ + met met nicotinate Mg Mg a cation a cation K + L-fucose L-fucose L-quinate L-quinate L-quinate ammonium UDP ammonium ammonium H O pro met amino acid a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar K oxaloacetate L-carnitine L-carnitine L-carnitine 2 phosphate quinic acid brain-specific hypothetical hypothetical hypothetical hypothetical -

187124736.Pdf

EVALUATING APOENZYME-COENZYME-SUBSTRATE INTERACTIONS OF METHANE MONOOXYGENASE WITH AN ENGINEERED ACTIVE SITE FOR ELECTRON-HARVESTING: A COMPUTATIONAL STUDY A Thesis by SIKAI ZHANG Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Chair of Committee, Sandun Fernando Co-Chair of Committee, R. Karthikeyan Committee Member, Carmen Gomes Head of Department, Steve Searcy December 2017 Major Subject: Biological and Agricultural Engineering Copyright 2017 Sikai Zhang ABSTRACT Energy generation via natural gas is viewed as one of the most promising environmentally friendly solutions for ever-increasing energy demand. Of the several alter- natives available, natural gas-powered fuel cells are considered to be one of the most efficient for producing energy. Biocatalysts, present in methanotrophs, known as methane monooxygenases (MMOs) are well known for their ability to quite effectively activate and oxidize methane at low- temperature. To utilize MMOs effectively in a fuel cell, the enzymes should be directly attached onto the anode. However, there is a knowledge gap on how to attach MMOs to an electrode and once attached the impact of active site modification on enzyme functionality. The overall goal of this work was to computationally evaluate the feasibility of attaching MMOs to a metal electrode and evaluate its functionality using docking and molecular dynamic (MD) simulations. It is surmised that MMOs could be attached to a metal electrode by engineering the active site, i.e., Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD) coenzyme to attract metal clusters (surfaces) via Fe-S functionalization and such modification will keep the active site functionality unfettered. -

Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0131395 A1 Antonelli Et Al

US 20090131395A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0131395 A1 Antonelli et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 21, 2009 (54) BIPHENYLAZETIDINONE CHOLESTEROL Publication Classification ABSORPTION INHIBITORS (51) Int. Cl. (75) Inventors: Stephen Antonelli, Lynn, MA A 6LX 3L/397 (2006.01) (US); Regina Lundrigan, C07D 205/08 (2006.01) Charlestown, MA (US); Eduardo J. A6IP 9/10 (2006.01) Martinez, St. Louis, MO (US); Wayne C. Schairer, Westboro, MA (52) U.S. Cl. .................................... 514/210.02:540/360 (US); John J. Talley, Somerville, MA (US); Timothy C. Barden, Salem, MA (US); Jing Jing Yang, (57) ABSTRACT Boxborough, MA (US); Daniel P. The invention relates to a chemical genus of 4-biphenyl-1- Zimmer, Somerville, MA (US) phenylaZetidin-2-ones useful in the treatment of hypercho Correspondence Address: lesterolemia and other disorders. The compounds have the HESLN ROTHENBERG EARLEY & MEST general formula I: PC S COLUMBIA. CIRCLE ALBANY, NY 12203 (US) (73) Assignee: MICROBIA, INC., Cambridge, MA (US) “O O (21) Appl. No.: 11/913,461 o R2 R4 X (22) PCT Filed: May 5, 2006 R \ / (86). PCT No.: PCT/USO6/17412 S371 (c)(1), (2), (4) Date: May 30, 2008 * / Related U.S. Application Data (60) Provisional application No. 60/677,976, filed on May Pharmaceutical compositions and methods for treating cho 5, 2005. lesterol- and lipid-associated diseases are also disclosed. US 2009/013 1395 A1 May 21, 2009 BPHENYLAZETIONONE CHOLESTEROL autoimmune disorders, (6) an agent used to treat demylena ABSORPTION INHIBITORS tion and its associated disorders, (7) an agent used to treat Alzheimer's disease, (8) a blood modifier, (9) a hormone FIELD OF THE INVENTION replacement agent/composition, (10) a chemotherapeutic 0001.