The Ghetto Fights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aufstieg Und Fall Von Jürgen Stroop (1943-1952): Von Der Beförderung Zum Höheren SS- Und Polizeiführer Bis Zur Hinrichtung

Aufstieg und Fall von Jürgen Stroop (1943-1952): von der Beförderung zum Höheren SS- und Polizeiführer bis zur Hinrichtung. Eine Analyse zur Darstellung seiner Person anhand ausgewählter Quellen. Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Magistra der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Beatrice BAUMGARTNER am Institut für Geschichte Begutachter: Univ.-Doz. Dr. Klaus Höd Graz, 2019 Ehrenwörtliche Erklärung Ich erkläre ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen nicht benutzt und die Quellen wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen inländischen oder ausländischen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Die vorliegende Fassung entspricht der eingereichten elektronischen Version. Datum: Unterschrift: I Gleichheitsgrundsatz Aus Gründen der Lesbarkeit wird in der Diplomarbeit darauf verzichtet, geschlechterspezifische Formulierungen zu verwenden. Soweit personenbezogene Bezeichnungen nur in männlicher Form angeführt sind, beziehen sie sich auf Männer und Frauen in gleicher Weise. II Danksagung In erster Linie möchte ich mich bei meinem Mentor Univ.-Doz. Dr. Klaus Hödl bedanken, der mir durch seine kompetente, freundliche und vor allem unkomplizierte Betreuung das Verfassen meiner Abschlussarbeit erst möglich machte. Hoch anzurechnen ist ihm dabei, dass er egal zu welcher Tages- und Nachtzeit -

British Responses to the Holocaust

Centre for Holocaust Education British responses to the Insert graphic here use this to Holocaust scale /size your chosen image. Delete after using. Resources RESOURCES 1: A3 COLOUR CARDS, SINGLE-SIDED SOURCE A: March 1939 © The Wiener Library Wiener The © AT FIRST SIGHT… Take a couple of minutes to look at the photograph. What can you see? You might want to think about: 1. Where was the photograph taken? Which country? 2. Who are the people in the photograph? What is their relationship to each other? 3. What is happening in the photograph? Try to back-up your ideas with some evidence from the photograph. Think about how you might answer ‘how can you tell?’ every time you make a statement from the image. SOURCE B: September 1939 ‘We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who is so bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack on her people.’ © BBC Archives BBC © AT FIRST SIGHT… Take a couple of minutes to look at the photograph and the extract from the document. What can you see? You might want to think about: 1. The person speaking is British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. What is he saying, and why is he saying it at this time? 2. Does this support the belief that Britain declared war on Germany to save Jews from the Holocaust, or does it suggest other war aims? Try to back-up your ideas with some evidence from the photograph. Think about how you might answer ‘how can you tell?’ every time you make a statement from the sources. -

Samuel Maharero Portrait

SAMUEL MAHARERO (1856-1923) e id Fig noc hter against ge Considered the first genocide of the 20th century, forerunner to the Holocaust, between 1904-08 the German army committed acts of genocide against groups of blackHEROIC people RESISTANCE in German TO South THE . NATIONAL HERO West Africa. Samuel Maharero’s by the German army has made him a MASSACRE First they came for the Gustav Schiefer communists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Esther Brunstein Anti Nazi Trade Unionist communist; Primo Levi Survivor and Witness (b. 1876) Then they came for the socialists, han Noor k Chronicler of Holocaust (1928- ) Gustav Schiefer, Munich Chairman and I did not speak out—because Anne Frank Courageous Fighter (1919-1987) Esther Brunstein was born in of the German Trade Union I was not a socialist; Lodz, Poland. When the Nazis Association, was arrested, Leon Greenman Diarist (1929-1945) (1914-1944) Primo Levi was born in Turin, beaten and imprisoned in Dachau Then they came for the trade eil Italy. He was sent to Auschwitz invaded in 1939 she was forced to Simone v Witness to a new Born in Frankfurt-am-Maim in Born to an Indian father and concentration camp. Members unionists, and I did not speak in 1944. Managing to survive wear a yellow star identifying her Germany, Anne Frank’s family American mother in Moscow, of trade unions and the Social out—because I was not a trade Holocaust survivor and generation (1910-2008) he later penned the poignant as a Jew. In 1940 she had to live went to Holland to escape Nazi Noor Khan was an outstandingly If this be a Democratic Party were targeted by politician (1927- ) Born in London and taken and moving book in the Lodz ghetto. -

Supplemental Assets – Lesson 6

Supplemental Assets – Lesson 6 The following resources are from the archives at Yad Vashem and can be used to supplement Lesson 6, Jewish Resistance, in Echoes and Reflections. In this lesson, you learn about the many forms of Jewish resistance efforts during the Holocaust. You also consider the risks of resisting Nazi domination. For more information on Jewish resistance efforts during the Holocaust click on the following links: • Resistance efforts in the Vilna ghetto • Resistance efforts in the Kovno ghetto • Armed resistance in the Sobibor camp • Resistance efforts in Auschwitz-Birkenau • Organized resistance efforts in the Krakow ghetto: Cracow (encyclopedia) • Mordechai Anielewicz • Marek Edelman • Zvia Lubetkin • Rosa Robota • Hannah Szenes In this lesson, you meet Helen Fagin. Learn more about Helen's family members who perished during the Holocaust by clicking on the pages of testimony identified with a . For more information about Jan Karski, click here. In this lesson, you meet Vladka Meed. Learn more about Vladka's family members who perished during the Holocaust by clicking on the pages of testimony identified by a . Key Words • The "Final Solution" • Jewish Fighting Organization, Warsaw (Z.O.B.) • Oneg Shabbat • Partisans • Resistance, Jewish • Sonderkommando Encyclopedia • Jewish Military Union, Warsaw (ZZW) • Kiddush Ha-Hayim • Kiddush Ha-Shem • Korczak, Janusz • Kovner, Abba • Holocaust Diaries • Pechersky, Alexandr • Ringelblum, Emanuel • Sonderkommando • United Partisan Organization, Vilna • Warsaw Ghetto Uprising • -

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Commemoration

Der Partizaner-himen––Hymn of the Partisans Annual Gathering Commemorating Words by Hirsh Glik; Music by Dmitri Pokras Wa rsaw Ghetto Uprising Zog nit keyn mol az du geyst dem letstn veg, The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising khotsh himlen blayene farshteln bloye teg. Commemoration Kumen vet nokh undzer oysgebenkte sho – s'vet a poyk ton undzer trot: mir zaynen do! TODAY marks the 75th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Each April 19th, survivors, the Yiddish cultural Fun grinem palmenland biz vaysn land fun shney, community, Bundists, and children of resistance fighters and mir kumen on mit undzer payn, mit undzer vey, Holocaust survivors gather in Riverside Park at 83rd Street at 75th Anniversary un vu gefaln s'iz a shprits fun undzer blut, the plaque dedicated to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in order to shprotsn vet dort undzer gvure, undzer mut! mark this epic anniversary and to pay tribute to those who S'vet di morgnzun bagildn undz dem haynt, fought and those who perished in history’s most heinous crime. un der nekhtn vet farshvindn mit dem faynt, On April 19, 1943, the first seder night of Passover, as the nor oyb farzamen vet di zun in dem kayor – Nazis began their liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, a group of vi a parol zol geyn dos lid fun dor tsu dor. about 220 out of 50,000 remaining Jews staged a historic and Dos lid geshribn iz mit blut, un nit mit blay, heroic uprising, holding the Nazis at bay for almost a full month, s'iz nit keyn lidl fun a foygl oyf der fray. -

Europe and the World in the Face of the Holocaust

EUROPE AND THE WORLD subject IN THE FACE OF THE HOLOCAUST – PASSIVITY AND COMPLICITY Context6. Societies in all European countries, death camps. Others actively helped the whether fighting against the Germans, Germans in such campaigns ‘in the field’ occupied by or collaborating with them, or carried out in France, the Baltic States, neutral ones, faced an enormous challenge Romania, Hungary, Ukraine and elsewhere. in the face of the genocide committed against Jews: how to react to such an enormous After the German attack on France in June crime? The attitudes of specific nations as well 1940, the country was divided into two zones: as reactions of the governments of the occupied Northern – under German occupation, and countries and the Nazi-free world to the Holocaust Southern – under the jurisdiction of the French continue to be a subject of scholarly interest and state commonly known as Vichy France (La France great controversy at the same time. de Vichy or Le Régime de Vichy) collaborating with the Germans. Of its own accord, the Vichy government Some of them, as noted in the previous work sheet, initiated anti-Jewish legislation and in October guided by various humanitarian, religious, political, 1940 and June 1941 – with consent from head of personal or financial motives, became involved in state Marshal Philippe Petain – issued the Statuts aiding Jews. There were also those, however, who des Juifs which applied in both parts of France and exploited the situation of Jews for material gain, its overseas territories. They specified criteria for engaged in blackmail, denunciation and even determining Jewish origin and prohibited Jews murder. -

Education About Auschwitz and the Holocaust at Authentic Memorial Sites CURRENT STATUS and FUTURE PROSPECTS

Education about Auschwitz and the Holocaust at Authentic Memorial Sites CURRENT STATUS AND FUTURE PROSPECTS edited by Piotr Trojański Education about Auschwitz and the Holocaust at Authentic Memorial Sites CURRENT STATUS AND FUTURE PROSPECTS edited by Piotr Trojański AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU STATE MUSEUM OŚWIĘCIM 2019 Review: Professor Jacek Chrobaczyński, Ph. D. Co-ordination: Katarzyna Odrzywołek Language review of the English version: Imogen Dalziel Translation of texts from German and English: Kinga Żelazko and Junique Translation Agency Setting and e-pub: Studio Grafpa Cover design: Studio Grafpa ISBN 9788377042847 © Copyright by Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum & the Authors The publication was created as part of a project implemented by the International Centre for Education about Auschwitz and the Holocaust, entitled ‘The Future of Auschwitz and Holocaust Education in Authentic Memorial Sites’, which was financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Table of Contents Introduction ........................................... 6 Part 1: Challenges Bartosz Bartyzel Educational Challenges at the Authentic Auschwitz Memorial Site ..... 11 Piotr Tarnowski Educational Challenges at the Stutthof Museum and Memorial Site from the Perspective of a Museum Pedagogue ..................... 19 Małgorzata Grzanka Education at the Museum of the Former German Extermination Camp Kulmhof in Chełmno-on-the-Ner ......................... 25 Joanna Podolska What do the Stones Tell Us? Education and Memory of the Place: The Example of the Bałuty District and the Łódź Ghetto in the Activity of the Dialogue Centre .......................... 39 Part 2: Prospects Marek Kucia and Katarzyna Stec Education about Auschwitz and the Holocaust from the Perspective of Social Research ................................. 60 Alicja Bartuś On How to React to Evil: A Visit to Auschwitz and Attitude Shaping .. -

Gazeta Spring/Summer 2021

Volume 28, No. 2 Gazeta Spring/Summer 2021 Wilhelm Sasnal, First of January (Side), 2021, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw A quarterly publication of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies and Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Editorial & Design: Tressa Berman, Daniel Blokh, Fay Bussgang, Julian Bussgang, Shana Penn, Antony Polonsky, Aleksandra Sajdak, William Zeisel, LaserCom Design, and Taube Center for Jewish Life and Learning CONTENTS Message from Irene Pipes ............................................................................................... 4 Message from Tad Taube and Shana Penn ................................................................... 5 FEATURES Lucy S. Dawidowicz, Diaspora Nationalist and Holocaust Historian ............................ 6 From Captured State to Captive Mind: On the Politics of Mis-Memory Tomasz Tadeusz Koncewicz ................................................................................................ 12 EXHIBITIONS New Legacy Gallery at POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Tamara Sztyma .................................................................................................................... 16 Wilhelm Sasnal: Such a Landscape. Exhibition at POLIN Museum ........................... 20 Sweet Home Sweet. Exhibition at Galicia Jewish Museum Jakub Nowakowski .............................................................................................................. 21 A Grandson’s -

Commemoration of the Anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on April 19, 1943 by Gary Tischler

Commemoration of the Anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on April 19, 1943 by Gary Tischler Today is April 19. It is an anniversary, of an event that from start to finish—preceded and was followed by events that exposed once and for all the true outlines of what the Nazis euphemistically called the Final Solution It lasted barely a month, but has proven to be unforgettable in its echoing impact. On April 19, in the city of Warsaw and a place called the Warsaw Ghetto, where thousands of Jews had been herded and separated from the city proper in the aftermath of the German invasion of Poland in 1939, the remaining Jews in the Ghetto, faced with deportation to the “East,’ specifically the extermination camp at Treblinka, rose up and defied the German SS General Jürgen Stroop’s order to cease resistance of any sort. As German troops, including a large number of veteran Waffen SS troops, entered the ghetto on the eve of Passover, the Jewish holiday of freedom. Organized Jewish resistance fighters fought back, and for a month battled German forces, with all the courage of a David fighting an implacable Goliath. In the end, using a limited amount of weapons—some rifles, pistols, Molotov cocktails, grenades-- these fighters staved off the Germans, inflicted numerous casualties, and fought bitterly, with little hope, but outsized courage. Many of the survivors and the historians of this conflict, which ended when Stroop used dynamite and fire to burn out the fighters and the remaining residents, told others that they fought so that they could stand up and resist, to die honorable deaths in the face of certain destruction. -

Holocauststudies 2017 02 Form the Editor.Indd

From the editor This volume contains a selection of articles from Holocaust. Studies and Materials published by the Centre for Holocaust Research during 2014–2016. This is already the fourth English volume intended to familiarise the foreign reader with the newest Polish research on the Holocaust and also introducing unknown documents from Polish archives into scholarly circulation. The previous editions were published in 2008, 2010, and 2013. The several dozen texts in this volume are arranged in an order modelled on the Polish-language version, though it was decided not to include a selection of the reviews printed in our periodical. The irst section, Studies, contains six texts. The article opening this volume is Jan Grabowski’s text that reveals new facts regarding the March 1944 discovery of the bunker where Emanuel Ringelblum, the Oneg Shabbat founder, was hiding. This study sheds new light on the mechanism of tracking down Jews in Warsaw. Grabowski’s analysis of post-war court iles proves that specialised groups of criminal police functionaries played an extremely active role in those efforts. Barbara Engelking’s study, which also regards the Warsaw context, discusses the help provided to about a dozen Jews by a pre-war avowed anti-Semite. It is not a simple and unambiguous case, however, because after the war that Pole was tried for having acted to the detriment of other Jews. Another of our authors, Dariusz Libionka, presents the reactions of the Polish Government in exile, its consulting body, the National Council of Poland, and the Polish press published in London to the struggle waged by the Warsaw ghetto in April and May 1943. -

Drucksache 19/1557 19

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/1557 19. Wahlperiode 06.04.2018 Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Brigitte Freihold, Jan Korte, Dr. Petra Sitte, Doris Achelwilm, Gökay Akbulut, Simone Barrientos, Sevim Dağdelen, Dr. Diether Dehm, Anke Domscheit-Berg, Christine Buchholz, Andrej Hunko, Stefan Liebich, Cornelia Möhring, Norbert Müller (Potsdam), Zaklin Nastic, Thomas Nord, Sören Pellmann, Helin Evrim Sommer, Alexander Ulrich, Kathrin Vogler, Katrin Werner und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. Gedenken an den jüdischen Widerstand anlässlich des 75. Jahrestages der Aufstände im Warschauer Ghetto und den deutschen Vernichtungslagern Treblinka und Sobibor In Jahr 2018 begeht die internationale Staatengemeinschaft den 75. Jahrestag des Aufstandes im Warschauer Ghetto vom 19. April 1943 sowie der Aufstände in den deutschen Vernichtungslagern Treblinka vom 2. August 1943 und Sobibor vom 14. Oktober 1943. Diese bewaffneten Erhebungen stellen – neben dem Auf- stand des jüdischen Sonderkommandos in Auschwitz-Birkenau am 7. Oktober 1944 – die eindrücklichsten Beispiele des Widerstands durch Jüdinnen und Juden gegen den Nationalsozialismus und den Holocaust dar. Dabei sind sie nicht die einzigen, denn in den über 1 100 Ghettos im deutsch besetzten Osteuropa kam es zu zahlreichen Erhebungen gegen die Okkupanten (vgl. www.yadvashem.org/ de/holocaust/about/combat-resistance.html, www.yadvashem.org/de/holocaust/ about/combat-resistance/warsaw-ghetto.html, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Aufstand_von_Treblinka, www.spiegel.de/einestages/kz-aufstand-sobibor- ausbruch-aus-dem-konzentrationslager-a-951287.html). Die Massenmorde der Deutschen im besetzten Osteuropa, insbesondere die sys- tematische Erschießung von schätzungsweise 55 000 bis 70 000 Jüdinnen und Ju- den in Ponary bei Wilna, die seit Ende 1941 in Betrieb genommenen deutschen Vernichtungslager und die ersten Aktionen zur gewaltsamen Auflösung bestehen- der Ghettos führten zu einer Konsolidierung des jüdischen Widerstandes. -

2022 Poland Affinity LAYERS.Indd

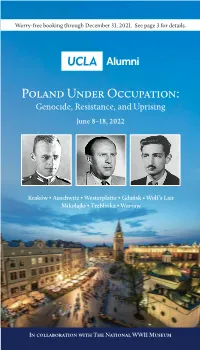

Worry-free booking through December 31, 2021. See page 3 for details. Poland Under Occupation: Genocide, Resistance, and Uprising June 8–18, 2022 Kraków • Auschwitz • Westerplatte • Gdańsk • Wolf’s Lair Mikolajki • Treblinka • Warsaw In collaboration with The National WWII Museum MOTHER AND DAUGHTER REFLECT ON OMAHA BEACH. RUSSIAN FLAG IS FLOWN OVER THE RUINS OF THE REICHSTAG / WORLD HISTORY ARCHIVE / ALAMY Travel with Confidence No cancellation fees on select tours until December 31, 2021 Dear UCLA Alumni and Friends, To allow you to book your next trip with peace of mind, we have set up our To fully comprehend World War II, one needs to understand its origins. In Europe, exceptional and flexibleWorry-Free Booking program that allows you to cancel the journey to war began in the private meeting rooms and raucous public or postpone your trip penalty-free until December 31, 2021. Please contact our stadiums of Germany where the Nazis concocted and then promoted their reservations department to discuss your options. designs for a new world order, one founded on conquest and racial-purity ideals. As they launched the war by invading Poland on September 1, 1939, Hitler and his followers unleashed a hell that would cause immense suffering and leave the country vulnerable to Stalin’s post-war ambitions for Soviet expansion. Through the German occupation and the following decades of Soviet oppression, the Polish people held strong in their push for freedom. World figures such as Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and Pope John Paul II gave their support for a free Poland and bolstered the internal efforts of Lech Walesa, Władysław Bartoszewski, and many others inside Poland.