Dietary Sources of Fluoride for Infants and Children in Hong Kong Faiez N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soda Handbook

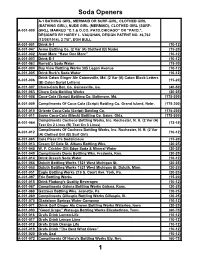

Soda Openers A-1 BATHING GIRL, MERMAID OR SURF-GIRL, CLOTHED GIRL (BATHING GIRL), NUDE GIRL (MERMAID), CLOTHED GIRL (SURF- A-001-000 GIRL), MARKED “C.T.& O.CO. PATD.CHICAGO” OR “PATD.”, DESIGNED BY HARRY L. VAUGHAN, DESIGN PATENT NO. 46,762 (12/08/1914), 2 7/8”, DON BULL A-001-001 Drink A-1 (10-12) A-001-047 Acme Bottling Co. (2 Var (A) Clothed (B) Nude) (15-20) A-001-002 Avon More “Have One More” (10-12) A-001-003 Drink B-1 (10-12) A-001-062 Barrett's Soda Water (15-20) A-001-004 Bay View Bottling Works 305 Logan Avenue (10-12) A-001-005 Drink Burk's Soda Water (10-12) Drink Caton Ginger Ale Catonsville, Md. (2 Var (A) Caton Block Letters A-001-006 (15-20) (B) Caton Script Letters) A-001-007 Chero-Cola Bot. Co. Gainesville, Ga. (40-50) A-001-063 Chero Cola Bottling Works (20-25) A-001-008 Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Baltimore, Md. (175-200) A-001-009 Compliments Of Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Grand Island, Nebr. (175-200) A-001-010 Oriente Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. (175-200) A-001-011 Sayre Coca-Cola (Block) Bottling Co. Sayre, Okla. (175-200) Compliments Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var (A) A-001-064 (12-15) Text On 2 Lines (B) Text On 3 Lines) Compliments Of Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var A-001-012 (10-12) (A) Clothed Girl (B) Surf Girl) A-001-065 Cola Pleez It's Sodalicious (15-20) A-001-013 Cream Of Cola St. -

We Feature Spirits from Artisan Distillers Who Bring Their Love of Craft to Life in Every Sip

WE FEATURE SPIRITS FROM ARTISAN DISTILLERS WHO BRING THEIR LOVE OF CRAFT TO LIFE IN EVERY SIP. 4828 E. 2ND ST. LONG BEACH, CA 90803 SAINTANDSECOND.COM SPECIALTY COCKTAILS S&S MOSCOW MULE 13.75 MY PALOMA 15.5 Christiania Vodka, housemade agave ginger Gran Dovejo Tequila, fresh citrus, agave syrup, Q sparkling soda, fresh lime nectar, Q grapefruit soda, black lava salt •Substitute Redbreast 12yr Old Whiskey THE MARY 13 for Saint Irish Mule Christiania Vodka, housemade Bloody Mary mix, blue cheese olives, celery MY TWO FAVORITE THINGS 16 Neft Vodka, Lustau Vermut Rosé, orange bitters BELMONT SHORE ICED TEA 13.5 Copper & Kings Immature Brandy, Sun GINNY FROM THE BLOCK 15 American Gin, Giffard Orange Curaçao Sipsmith Gin, Italicus Rosolio di Bergamotto, Liqueur, fresh lemon juice, cane sugar, cold-pressed cranberry juice, orange blossom cold-pressed cranberry juice honey, mint, fresh lime "Name the Cocktail Contest" Winner: DARK & STORMY 13.5 Candace Lee, Long Beach Goslings Black Seal Rum, housemade ginger syrup, fresh lime juice, Q soda water POW 13.5 PAU Maui Vodka, housemade pineapple syrup, SMOKE SIGNALS 14.5 basil, fresh lime, ginger ale Wahaka Mezcal, Ghost Pepper Tequila, Maestro Dobel Blanco Tequila, agave nectar, FEEL THE RUSH 13.5 fresh grapefruit, Q grapefruit soda, Smooth Ambler Contradiction Bourbon, black lava salt honey, lemon, peach purée, peach bitters DESIGNER SMOKES 17 THE GOOD, THE BAD & THE SMOKY 16 Legendario Domingo Mezcal, Gran Classico Koval Rye, Luxardo Bitter Bianco, Bitter, vermouth blend, grapefruit twist Velvet Falernum, bitters, clove smoke FRAMBUESA 15 S&S MANHATTAN 16 Herradura Reposado Tequila, Aperol, Rittenhouse Rye, Lustau East India Solera ginger syrup, lime juice, raspberries Sherry, Cocchi Vermouth, aromatic bitters THE ICON 16 Olive-washed Christiania Vodka, Dolin Dry Vermouth, blue cheese olives MIMOSA TRAY SERVED WITH THREE SEASONAL JUICES AND ASSORTED FRESH BERRIES. -

Inventory Price List

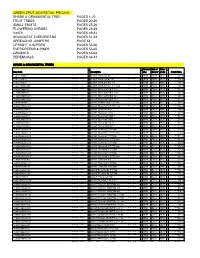

GREEN SPOT 2020 RETAIL PRICING SHADE & ORNAMENTAL TREE PAGES 1-20 FRUIT TREES PAGES 20-25 SMALL FRUITS PAGES 25-26 FLOWERING SHRUBS PAGES 26-49 VINES PAGES 49-51 BROADLEAF EVERGREENS PAGES 51-53 SPREADING JUNIPERS PAGE 54 UPRIGHT JUNIPERS PAGES 55-56 EVERGREENS & PINES PAGES 56-65 GRASSES PAGES 65-68 PERENNIALS PAGES 68-81 SHADE & ORNAMENTAL TREES Product Unit of Price Item Code Description Line Measur Code Retail Price e 10-ALDTHIN#10 ALDER, THINLEAF #10 SOTR EACH RETL 131.95 10-ALDTHIN05' ALDER, THINLEAF #7 (5') SOTR EACH RETL 105.85 10-ALDTHIN06' ALDER, THINLEAF #15 (6') SOTR EACH RETL 145.00 10-ALDTHINCL8BB ALDER, THINLEAF CL. 8.00' B&B SOTR EACH RETL 384.25 10-ASPENMNT1.5 ASPEN, MTN. SENTINEL 1.50" SOTR EACH RETL 227.65 10-ASPENMNT1.7 ASPEN, MTN. SENTINEL 1.75" SOTR EACH RETL 329.15 10-ASPENMNTSE15 ASPEN, MTN. SENTINEL 1.25 SOTR EACH RETL 227.65 10-ASPENMNTSEN ASPEN, MTN. SENTINEL 2.50" SOTR EACH RETL 500.25 10-ASPENPRA8 ASPEN, PRAIRIE GOLD 8-10BB SOTR EACH RETL 333.50 10-ASPENQU100CL ASPEN, QUAKING COLLECTED SOTR EACH RETL 145.00 10-ASPENQUA#10 ASPEN, QUAKING #7CL SOTR EACH RETL 108.75 10-ASPENQUA#10C ASPEN, QUAKING #10CL SOTR EACH RETL 143.55 10-ASPENQUA#15 ASPEN, QUAKING #15CL SOTR EACH RETL 210.25 10-ASPENQUA#15C ASPEN, QUAKING #15CL SOTR EACH RETL 210.25 10-ASPENQUA#20 ASPEN, QUAKING #20 CL SOTR EACH RETL 290.00 10-ASPENQUA#5C ASPEN, QUAKING #5CL SOTR EACH RETL 71.05 10-ASPENQUA150F ASPEN, QUAKING 1.50" B&B SOTR EACH RETL 221.85 10-ASPENQUA175C ASPEN, QUAKING 1.75" CL B&B SOTR EACH RETL 278.40 10-ASPENQUA175F ASPEN, QUAKING -

County-Clare-Drink-Menu.Pdf

Draft Bottle Ask for a sample. No refunds Clare Cocktails based on taste preference. Ireland Ireland Magner’s Pear Cider Milwaukee Mule Tango Fizz Guinness Stout Germany Our twist on the Moscow Tequila, mango and Murphy’s Stout Clausthauler Amber N/A Mule: Rehorst Premium club soda Smithwick’s Red Ale Bitburger Drive N/A Vodka, ginger beer with Kilkenny Cream Ale squeeze of fresh lime. Wisconsin Old Harp Lager England Magner’s Cider Fashioned Blackthorn Dry Cider Irish Mule Hand muddled, Wisconsin Irish whiskey, ginger beer style. Choose whiskey or Denmark and lime. Carlsberg Lager Wisconsin brandy. Sweet, sour or with Lakefront New Grist Gluten Free club soda. Belgium Pabst Blue Ribbon Infamous Golfer Grimbergen Dubbel - $7 Miller Lite A wonderfully refreshing Sweet Caroline Coors Light mix of Rehorst Citrus & Irish whiskey, lemonade, Bud Light Honey Premium Vodka, club soda, Chambord. Germany lemonade and iced tea. An Franziskaner New York Arnold Palmer with a kick! Purple Rain England Ommegang Pale Sour Irish Lemonade Vodka, pineapple juice, Fuller’s black currant. Originated here at County American Craft “Work is the Clare: Rehorst Citrus & Bell’s Seasonal Honey Premium Vodka, Milwaukee Breeze curse of the lemonade and a splash of A refreshing cocktail Wisconsin black currant juice. featuring Rehorst Premium Gin, seltzer, cranberry juice Spotted Cow drinking and fresh lime. Third Space Happy Place classes.” Import 20 oz. - $6 ~ Oscar Wilde Domestic Craft - $5 Desserts Ask about our seasonal and rotating taps not listed here. Seasonal Crème Brûlée Delicate seasonally flavored custard with a crispy caramelized sugar topping. Finished with a Specialty Tap dollop of fresh whipped cream. -

Ftc Volume Decision 91

" " " " " " .. .... .." " " " " " " "" " " " " " , " , " , " ...- - . .." ..- 548 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION DECISIONS Initial Decision 91 F. will receive a fair and equitable compensation for the investment has made in developing his territory" (Smith, Tr. 616). Bottlers can acquire another bottler without the approval of "Coca-Cola" through a stock acquisition (Smith , Tr. 628). " Coca-Cola " if asked, has recom mended that bottlers merge or consolidate where appropriate (Smith Tr. 615-16). However, bottlers are independent businessmen who make their own independent decisions and who frequently a~t contrary to the advice of "Coca-Cola" (Smith, Tr. 615-16). (36) Competition in the Soft Drink Industry Generally 88. There is intense competition in the sale of flavored carbonated soft drinks which stems from the fact that there is a large number of brands available to the consumer in local markets. In 1971, a Neilsen Survey showed that there were 135 different brands of cola flavored soft drinks marketed in food stores (Smith, Tr. 705). In the Washing ton, D. , metropolitan area alone, there are over 30 brands of colas being marketed (Sales, Tr. 1243-1251). In addition to the cola brands more than 20 other brands of flavors such as root beer, orange gingerale, and lemon-lime were being sold in the Washington, D. market (Sales, Tr. 1243, 1255; CX 372; CX 373). In the territory of the Newport News , Virginia bottler of Coca-Cola, between 30 and 40 different brands of orange and grape soft drinks were being marketed (Brown, Tr. 1666). Over 176 different brands of flavored carbonated soft drinks were sold in the territory of The Coca-Cola Bottling Company of New York, Inc. -

Drink List Drinks

HAMBURGER ALLEE 2 FRANKFURT, HESSEN 60486 GERMANY +49 (0)69 7955-0 CHAMPIONS-FRANKFURT.DE E D @CHAMPIONSFRANKFURT . T R U F K N A R - F S N O P I M H A I N F O @ C DRINK LIST DRINKS #CHAMPIONSMARTINI 11 Gin, Apple, Riesling Vermouth, Orange Bitters YOUR HONEY'S MARGARITA 12 Tequila, Lime, Sage, Honey-Chamomile-Syrup, Salt-Rim CANTONA SOUR 11 Bourbon, Lemon, Redwine-Syrup, Egg White, Sichuan Pepper 8 BALL FIZZ 11 Gin, Earl Grey Tea, Lemon, Thyme, Vanilla, Soda BREAKFAST SMASH 12 Vodka, Lemon, Raspberry, Ginger-Syrup, Egg White ARE YOU ON DETOX? 8.5 Fizzy, Sour, Fruity, Creamy? Just tell us which mood are you and let us surprise you! HIGHBALLS 1.3.6.8 GARDEN AND TONIC 10 Gin, Chartreuse Jaune, Herbs, Tonic 1.2.3.4.6 DARK, STORMY AND SPICY 9 Bermuda Rum, Lime, Ginger Beer, Allspice Syrup, Bitters 1.2.3.4.6 FRANKFORT NECK 9 Bourbon, Lime, Pineapple, Ginger Ale 1.3.6.8 LADY CHATTERLEY 9 Lillet Blanc, White Portwine, Peychaud Bitters, Lime, Honey-Chamomile-Syrup, Tonic 1.2.3.4 CAPTAIN BARBOSSA 9 Rum, Lime, Riesling Wine, Mirinda A 12.13.14 BASIL AND IT 10 Gin, Lemon, Basil Soda, Sugar DRAFT & CRAFT FROM THE TAP 0.3L 0.5L 1.5L 3L Beck's 3.5 5 14.5 28 Binding Lager 3 4.5 13 25 Founder’s IPA 3.5 5 14.5 28 Franziskaner 3.5 5 14.5 28 Cellar Beer Franziskaner Pale 3.5 5 14.5 28 Spaten Pale 3.5 5 14.5 28 FROM THE NECK 0.33L 0.5L Beck’s Blue 3.5 Corona 5 Guinness 4.5 Franziskaner Cristal 5 Franziskaner Nonalcoholic 5 Franziskaner Stout 5 CRAFT AREA 0.33L Brooklyn East India IPA 6 Crew Republic Easy Summer 5.5 Crew Republic German Pale Ale 5.5 Crew Republic R.I.P. -

Charcuterie & Cheese

In compliance with Florida state guidelines and for the safety of our guests, all paper menus are disposed after each use. To view our full cocktail & wine list please visit LochBar.com, or scan the code provided soup sandwiches Served with choice of spring salad or boardwalk fries MARYLAND CRAB .............................. CUP $7 BOWL $12 mixed vegetable medley, purple potato, aromatic broth LOCH BURGER ................................................ $15 beef or turkey, LTO, cheddar, pickles, churchill sauce, kaiser bun CREAM OF CRAB ................................ CUP $7 BOWL $12 jumbo lump crab meat, leeks, cream, sherry shellfish towers ROASTED TURKEY CLUB ................................. $15 Chef’s selection of east & west coast oysters, clams, mussels, aioli, tomato, applewood smoked bacon, avocado, pumpernickel FRENCH ONION .................................................. $9 shrimp cocktail, alaskan king crab, maine lobster, & crudos. SALMON WRAP.............................................. $15 rich beef broth, caramelized onions, melted gruyére PETIT ................................................$65 prosciutto, sautéed spinach, roasted pepper, basil mayonnaise 6 Oysters ½ Lobster 6 Clams 4 Shrimp Cocktail PO BOY .......................................................... $16 salads 3 Mussels choice of shrimp or oyster, brussels sprouts coleslaw, Add: Chicken $5, Shrimp $8, Salmon $8, Tuna $12, Lobster $14 GRAND ............................................ $125 lettuce, tomato, housemade tartar sauce, sriracha aioli 12 -

ENCORP PACIFIC (CANADA) Registered Brands

ENCORP PACIFIC (CANADA) Registered Brands 1 7 10 Cal Aquafina Plus Vitamins 7 select 10 YEARS OIL PATCH TOUGH LONGHORN 7 Select Café 100 Plus 7 UP 100PLUS 7 up Lemon 1181 7-Select 1818 Alberni 7-SELECT 7-Up 2 7-Up 2 Guys With Knives 7D Mango Nectar 2% 7SELECT 24 Hour Collision Center 7Select 24 Mantra Mango Juice 7SELECT Natural Spring Water 24K 7UP 27 North 7up 28 Black 7up Lemon Lemon Sparkling Lemonade 3 8 3 The Terraces Three 80 Degrees 33 Acres Of Heart 80 Degrees North 33 Acres of Mineral 33 Acres of Pacific 9 33 Acres of Sunrise 9 MM Energy Drink 365 A 365 Everyday Value A & W 365 Organic Lemonade A (Futura) 365 Organic Limeade A&W 365 Whole Foods Market A&W Apple Juice 4 A&W Orange Juice 49th Parallel Cascara A-Team Mortgages 49th Parallel Cold Brew A2Z Capital 49th Parallel Grocery Abbott Wealth Management 49th Parallel Iced Tea Aberfoyle Springs 49th Parallel Sparkling Green Tea Abhishek Mehta-MarforiGroup, Mr Home Inspector ABK Restoration Services 5 Abstract Creating Iconic Spaces 5 Hour Energy Abstract Developments 5 Hour Energy Acapulcoco 5 Hour Energy Extra Strength Accelerade 5-hour Energy Extra Strength Access Roadside Assistance 5-HOUR EXTRA STRENGTH Accompass 52 North Beverages Acme Analytical Laboratories Ltd. 52° North Acqua Di Aritzia 59th Street Food Co. Acqua Filette 6 Acqua Italia 6 Hour Power Acqua Panna 601 West Hastings ACTIVATE BALANCE - Fruit Punch ACTIVATE BEAUTY - Exotic Berry ACTIVATE CHARGED - Lemon Lime Wednesday, September 01, 2021 The General Identification Guidelines should be read along with this brand registry listing. -

DHCIKJCADEMT. Overlooking the Futiil Plateau, Which Was URROGATES OFFICE.~EI|Za J

VOL. VII. NO. 43. HOBOKEN, N. J., SATURDAY, DECEMBER 10, 1881. PRICE THREE CENTS LEVELLING THE LANDMARKS. Weehawken ferry landing and dock, The dwelling occupied by Freeholder THEATRES. I DANCING ACADEMIES. CENTS' FURNISHING C00D5. i situated midway between tlio coal and Frost consists of two of the stone houses 1 oil docks. It, is, in truth, what it was COLEMAN. W'AHEISK !* GEKJI1MA TilEAl'KE Changes in and Around Weehawken built by the Dutch settlers oily lu.ndr. ' '» ANl«>fUMMEH (JAHbBN. Ninth Annual Opening called in 1819, a "very ancient ferry," and fifty years ago, and the walls are as ---The Great Tunnel-—Early NO. OH TO 7-1 HL'DW)N I ; —OF— Ooll, (luting from 1GB0. The boat used was stout as those of Fort Amsterdam in itsFor I/OIH! Irnitni/jit am! choif i/ootl*, Scenes, Etc. the Periauger, which was pointed at pulmy days. The oldest «tone IMJIIJI-- Hokoken, It. J. both ends, had two masts, but no bow-thero ivero throe of them-must ha'e —liO 'I O— The tarpri-st and IH-MI vemilat'-ti j-ltn-t- of ai | Mrs. Prof. F. Jurisch's sprit. When horses und wagons were been the llrst built in YW.-hawUon. uient in the eil)\ Men's FnmisMng U. A IHTRO strip of high land.tottiesoulh- New company even" week. fhaiiKe of pro^n carried over, the animals had to bo un- In HUD, Maryu Adria^nsei). n pi.iiN' COLEMAI.'S I DANCING ACADEMY, for (•ast of the mouth of tlio Wcchuwlci.'n harnessed and they and the vehicles evrry Monday and Thursday. -

I Drink to Make Other People More Interesting ONLY OVER 18 Ernest Hemingway

DRINKS BOOK I drink to make other people more interesting ONLY OVER 18 Ernest Hemingway SERVICE AU BAR Service au bar. L’abus d’alcool est dangereux pour la santé. A consommer avec modération. Prix nets TTC en euros. t t t SeasonalAsk your server guest for details beers t t t BEER DRAUGHT BIÈRE PRESSION BEFORE 8PM AFTER 8PM 25cl | 50cl 25cl | 50cl WALLACE IPA 5,5° - IPA 3.30€ | 5.50€ 3.80€ | 6.50€ Craft IPA brassée localement, dry-hopped aux Cascade & Citra, aux saveurs des agrumes et mangue. WALLACE DOUBLE IPA 7,5° - IPA 3.60€ | 6.00€ 4.10€ | 7.00€ Plus houblonnée, avec Simco & Centennial, pour des notes de pin & des agrumes GUINNESS 4,2° - Stout 3.30€ | 5.50€ 3.80€ | 6.50€ Arômes doux et torréfiés de malt évoquant le cacao, le café. LA CHOUFFE 8° - Pale Ale 4.00€ | 6.50€ 4.50€ | 7.50€ Arômes doux et torréfiés de malt évoquant le cacao, le café. BUDVAR 5° - Blonde 3.00€ | 5.50€ 3.50€ | 6.00€ Sèche et maltée en bouche avec une pointe de caramel BREWDOG PUNK IPA 5,6°- IPA 3.60€ | 6.00€ 4.10€ | 7.00€ Une écossaise aux saveurs fruitées évoquant la pêche et les fruits tropicaux ! Service au bar. L’abus d’alcool est dangereux pour la santé. A consommer avec modération. Prix nets TTC en euros. BEER DRAUGHT BIÈRE PRESSION BEFORE 8PM AFTER 8PM 25cl | 50cl 25cl | 50cl BREWDOG ELVIS JUICE 6,5°- IPA 3.60€ | 6.00€ 4.10€ | 7.00€ Grapefruit IPA - notes de pêche, agrumes, houblons et pamplemousse. -

Goedgekeurde Cultivars Japan Klik Op Het Gewas Om Naar De Juiste Pagina En Betreffende Lijst Te Gaan Vanaf Pagina ALLIUM

Goedgekeurde cultivars Japan Klik op het gewas om naar de juiste pagina en betreffende lijst te gaan vanaf pagina ALLIUM .............................. 2 BEGONIA ........................... 3 CROCUS ............................ 5 GLADIOLUS ...................... 6 HIPPEASTRUM ................. 8 HYACINTHUS .................... 12 IRIS .................................... 14 LILIIUM .............................. 18 TULIPA .............................. 42 De lijsten per gewas kunnen verschillende jaren/seizoenen betreffen. Het geldende jaar staat boven de lijst vermeld. ALLIUMALLIUM Japan goedgekeurde cultivars 2021 blz: 1 AFLATUNENSE ALBUM (CARINATUM SUBSP. PULCHELLUM) BALLERINA CARINATUM SUBSP PULCHELLUM COWANII CRISTOPHII EROS FLAVUM GLADIATOR GRACEFUL BEAUTY IVORY QUEEN JEANNINE KARATAVIENSE MOLY OREOPHILUM PURPLE SENSATION SCHUBERTII UNIFOLIUM URSINUM SUBSP URSINUM VIOLET BEAUTY Versie: 14-06-2021 Laatste pagina, aantal pagina's: 1 BEGONIABEGONIA Japan goedgekeurde cultivars 2020 blz: 1 AMERIHYBRID WIT (+ ROOD) AMERIHYBRID WIT (+ ROZE) BOUTON DE ROSE CALYPSO GEEL ORANJE CAMELLIA CASCADE FLORENCE CASCADE GEEL CASCADE ODOROSA CASCADE ODOROSA RED SUNSET CASCADE ODOROSA SWEET PINKCASCADE ODOROSA WHITE CASCADE ODOROSA YELLOW BLUSH FLAME CASCADE ORANJE CASCADE PASTEL CASCADE ROOD CASCADE ROZE CASCADE SCHARLAKEN CASCADE SUNRAY CASCADE WIT CASCADE ZALM DAFFODIL SALMON FIMBRIATA FLAMENCO WIT ROOD ILLUMINATION ABRIKOOS ILLUMINATION ORANJE ILLUMINATION ROZE ILLUMINATION SCHARLAKEN ILLUMINATION WIT LACE APRICOT LACE PINK LACE RED LACE SALMON -

Massive Sign Collection Auction Sunday, August 25Th - 2:00 PM 633 N Main Street, Bluffton, IN

Massive Sign Collection Auction Sunday, August 25th - 2:00 PM 633 N Main Street, Bluffton, IN 1 Have a Hires and Refresh Sign Metal 11 1/2" X 35" Metal 11 1/2" X 35" 2 Mason Root Beer Thermometer 16" x 6 16" x 6 3 Dr. Pepper Thermometer 27" X 8 1/2" 27" X 8 1/2" 4 Hussemans Soda Water Sign 11" X 6 1/2" 11" X 6 1/2" 5 We Serve NEHI Ice Cold Sign 19 1/2" x 3" 19 1/2" x 3" 6 Hires Root Beer Paper Display Sign 23 1/2" x 6" 23 1/2" x 6" 7 Thirsty or Not! Grapette Thermometer 16 1/2" x 4 1/2" 16 1/2" x 4 1/2" 8 RC Royal Crown Paper Display Sign 23 1/2" x 6" 23 1/2" x 6" 9 Drink Double Cola Thermometer 27" x 8" 27" x 8" 10 Tru Ade - Not Carbonated Thermometer 16" x 6" 16" x 6" 11 1949 Drink Squirt Calendar 12 The Perfect Fruit Drink Zesto 6" x 10 1/2" - Paper Sign Framed 6" x 10 1/2" - Paper Sign Framed 13 Real Orange -ade Green Spot 12" x 36" - Metal Sign 12" x 36" - Metal Sign 14 Coca Cola Thermometer 17" x 5 1/2" 17" x 5 1/2" 15 Teem Thermometer 28" x 12" 28" x 12" 16 Nichol Kola Metal Sign 12" x 29 1/2" 12" x 29 1/2" 17 Coca Cola Thermometer 28" x 8 1/2" 28" x 8 1/2" 18 Grapette Thermometer 15 1/2" x 6" 15 1/2" x 6" 19 Hires Since 1876 Root Beer Sign Thermometer 28" x 8" Metal 28" x 8" Metal Hires Root Beer Thermometer 28" x 8" - Missing 20 Thermometer 28" x 8" - Missing Thermometer 21 Coca Cola Thermometer 16" x 5" 16" x 5" 22 Dad's Root Beer Thermometer 27" x 7" 27" x 7" 23 Nu Grape Soda Thermometer 4" x 17" 4" x 17" "K-O" your thirst with KAYO - Chocolate Soda 24 1/2 " x 9" 24 Metal Sign 24 1/2 " x 9" Metal Sign (2) License Plates 1961