Landscape in the Sagas of Icelanders: the Concepts of Land and Landsleg Edda R.H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olof Sundqvist. Scripta Islandica 66/2015

SCRIPTA ISLANDICA ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK 66/2015 REDIGERAD AV LASSE MÅRTENSSON OCH VETURLIÐI ÓSKARSSON under medverkan av Pernille Hermann (Århus) Else Mundal (Bergen) Guðrún Nordal (Reykjavík) Heimir Pálsson (Uppsala) Henrik Williams (Uppsala) UPPSALA, SWEDEN Publicerad med stöd från Vetenskapsrådet. © Författarna och Scripta Islandica 2015 ISSN 0582-3234 Sättning: Ord och sats Marco Bianchi urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-260648 http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-260648 Innehåll LISE GJEDSSØ BERTELSEN, Sigurd Fafnersbane sagnet som fortalt på Ramsundsristningen . 5 ANNE-SOFIE GRÄSLUND, Kvinnorepresentationen på de sen vikinga- tida runstenarna med utgångspunkt i Sigurdsristningarna ....... 33 TERRY GUNNELL, Pantheon? What Pantheon? Concepts of a Family of Gods in Pre-Christian Scandinavian Religions ............. 55 TOMMY KUUSELA, ”Den som rider på Freyfaxi ska dö”. Freyfaxis död och rituell nedstörtning av hästar för stup ................ 77 LARS LÖNNROTH, Sigurður Nordals brev till Nanna .............. 101 JAN ALEXANDER VAN NAHL, The Skilled Narrator. Myth and Scholar- ship in the Prose Edda .................................. 123 WILLIAM SAYERS, Generational Models for the Friendship of Egill and Arinbjǫrn (Egils saga Skallagrímssonar) ................ 143 OLOF SUNDQVIST, The Pre-Christian Cult of Dead Royalty in Old Norse Sources: Medieval Speculations or Ancient Traditions? ... 177 Recensioner LARS LÖNNROTH, rec. av Minni and Muninn: Memory in Medieval Nordic Culture, red. Pernille Herrmann, Stephen A. Mitchell & Agnes S. Arnórsdóttir . 213 OLOF SUNDQVIST, rec. av Mikael Males: Mytologi i skaldedikt, skaldedikt i prosa. En synkron analys av mytologiska referenser i medeltida norröna handskrifter .......................... 219 PER-AXEL WIKTORSSON, rec. av The Power of the Book. Medial Approaches to Medieval Nordic Legal Manuscripts, red. Lena Rohrbach ............................................ 225 KIRSTEN WOLF, rev. -

Language Resources for Icelandic

Language Resources for Icelandic Sigrún Helgadóttir1,Eiríkur Rögnvaldsson2 (1)Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum, Reykjavík Iceland (2)University of Iceland, Reykjavík Iceland [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT We describe the current status of Icelandic language technology with respect to available language resources and tools. The recent META-NET survey of the state of language tech- nology support for 30 languages clearly demonstrated that Icelandic lags behind almost all European languages in this respect. However, it is encouraging that as a result of the META-NORD project, almost all basic language resources for Icelandic are now available through the META-SHARE repository and the local site http://www.málföng.is/, many of them in standard formats and under standard CC or GNU licenses. This is a major achievement since many of these resources have either been unavailable up to now or only available through personal contacts. In this paper, we describe briefly most of the major resources that have been made accessible through META-SHARE; their type, content, size, format, and license scheme. It is emphasized that even though these resources are extremely valuable as a basis for further R&D work, Icelandic language technology is far from having become self-sustaining and the Icelandic language technology community will need support from partners in the Nordic countries and Europe if Icelandic is to survive in the Digital Age. KEYWORDS: Icelandic, Language Resources, Repositories, Licenses. 1 Introduction According to the survey of language technology support for European languages recently conducted by META-NET (http://meta-net.eu) and published in the series “Europe’s Languages in the Digital Age”, Icelandic is among the European languages that have the least support (Rögnvaldsson et al., 2012). -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: April 28, 2006 I, Kristín Jónína Taylor, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Musical Arts in: Piano Performance It is entitled: Northern Lights: Indigenous Icelandic Aspects of Jón Nordal´s Piano Concerto This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Steven J. Cahn Professor Frank Weinstock Professor Eugene Pridonoff Northern Lights: Indigenous Icelandic Aspects of Jón Nordal’s Piano Concerto A DMA Thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College–Conservatory of Music 28 December 2005 by Kristín Jónína Taylor 139 Indian Avenue Forest City, IA 50436 (641) 585-1017 [email protected] B.M., University of Missouri, Kansas City, 1997 M.M., University of Missouri, Kansas City, 1999 Committee Chair: ____________________________ Steven J. Cahn, Ph.D. Abstract This study investigates the influences, both domestic and foreign, on the composition of Jón Nordal´s Piano Concerto of 1956. The research question in this study is, “Are there elements that are identifiable from traditional Icelandic music in Nordal´s work?” By using set theory analysis, and by viewing the work from an extramusical vantage point, the research demonstrated a strong tendency towards an Icelandic voice. In addition, an argument for a symbiotic relationship between the domestic and foreign elements is demonstrable. i ii My appreciation to Dr. Steven J. Cahn at the University of Cincinnati College- Conservatory of Music for his kindness and patience in reading my thesis, and for his helpful comments and criticism. -

Three Icelandic Outlaw Sagas

THREE ICELANDIC OUTLAW SAGAS THREE ICELANDIC OUTLAW SAGAS THE SAGA OF GISLI THE SAGA OF GRETTIR THE SAGA OF HORD VIKING SOCIETY FOR NORTHERN RESEARCH UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON 2004 Selection, introduction and other critical apparatus © J. M. Dent 2001 Translation of The Saga of Grettir and The Saga of Hord © J. M. Dent 2001 Translation of The Saga of Gisli © J. M. Dent 1963 This edition first published by Everyman Paperbacks in 2001 Reissued by Viking Society for Northern Research in 2004 Reprinted with minor corrections in 2014 ISBN 978 0 903521 66 6 The maps are based on those in various volumes of Íslensk fornrit. The cover illustration is of Grettir Ásmundarson from AM 426 fol., a late seventeenth-century Icelandic manuscript in Stofnun Árna Magnússonar á Íslandi, Reykjavík Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................................ vii Chronology .................................................................................... viii Introduction ..................................................................................... xi Note on the Text .......................................................................... xxvi THE SAGA OF GISLI ..................................................................... 1 THE SAGA OF GRETTIR ............................................................. 69 THE SAGA OF HORD ................................................................ 265 Text Summaries ........................................................................... -

History Or Fiction? Truth-Claims and Defensive Narrators in Icelandic Romance-Sagas

History or fiction? Truth-claims and defensive narrators in Icelandic romance-sagas RALPH O’CONNOR University of Aberdeen Straining the bounds of credibility was an activity in which many mediaeval Icelandic saga-authors indulged. In §25 of Göngu-Hrólfs saga, the hero Hrólfr Sturlaugsson wakes up from an enchanted sleep in the back of beyond to find both his feet missing. Somehow he manages to scramble up onto his horse and find his way back to civilisation – in fact, to the very castle where his feet have been secretly preserved by his bride-to-be. Also staying in that castle is a dwarf who happens to be the best healer in the North.1 Hann mælti: ‘… skaltu nú leggjast niðr við eldinn ok baka stúfana.’ Hrólfr gerði svâ; smurði hann þá smyrslunum í sárin, ok setti við fætrna, ok batt við spelkur, ok lèt Hrólf svâ liggja þrjár nætr. Leysti þá af umbönd, ok bað Hrólf upp standa ok reyna sik. Hrólfr gerði svâ; voru honum fætrnir þá svâ hægir ok mjúkir, sem hann hefði á þeim aldri sár verit. ‘He said, … “Now you must lie down by the fire and warm the stumps”. ‘Hrólfr did so. Then he [the dwarf] applied the ointment to the wounds, placed the feet against them, bound them with splints and made Hrólfr lie like that for three nights. Then he removed the bandages and told Hrólfr to stand up and test his strength. Hrólfr did so; his feet were then as efficient and nimble as if they had never been damaged.’2 This is rather hard to believe – but our scepticism has been anticipated by the saga-author. -

The Icelandic Language Free Download

THE ICELANDIC LANGUAGE FREE DOWNLOAD Stefan Karlsson,Rory McTurk | 84 pages | 20 Jun 2004 | Viking Society for Northern Research | 9780903521611 | English | London, United Kingdom Icelandic (Íslenska) Nilo-Saharan Language Family. A number of great literary works - the sagas - were written by Icelanders during the 12th and 13th centuries. The introduction of The Icelandic Language in the 11th century brought new religious terminology from other Scandinavian languages, The Icelandic Language. Many of the texts are based on poetry and laws traditionally preserved orally. Dravidian Language Family. I just tried using the kind of language my grandmother uses and put in Danish words every now and then and there was almost a complete understanding. Voice plays a primary role in the differentiation of most consonants including the nasals but excluding the plosives. Icelandic is a very The Icelandic Language language. As you can see, most place names in Iceland are very seethrough. It belongs with Norwegian and Faroese to the West Scandinavian group of North Germanic languages and developed from the Norse speech brought by settlers from western Norway in the The Icelandic Language and 10th centuries. Learn about the languages and dialects of the entire Nordic region with our interactive map. Language family. Nevertheless, the circumstances of the language were highly restricted until self-government developed The Icelandic Language the 19th century and Icelandic was rediscovered by Scandinavian scholars. Semitic Branch. Main article: History of Icelandic. Once you can see how the word is split up, then it becomes easier to pronounce. Arabic Egyptian Spoken. In most Icelandic families, the ancient tradition of patronymics is still in use; i. -

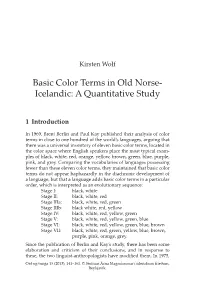

Basic Color Terms in Old Norse- Icelandic: a Quantitative Study

Kirsten Wolf Basic Color Terms in Old Norse- Icelandic: A Quantitative Study 1 Introduction In 1969, Brent Berlin and Paul Kay published their analysis of color terms in close to one hundred of the world’s languages, arguing that there was a universal inventory of eleven basic color terms, located in the color space where English speakers place the most typical exam- ples of black, white, red, orange, yellow, brown, green, blue, purple, pink, and grey. Comparing the vocabularies of languages possessing fewer than these eleven color terms, they maintained that basic color terms do not appear haphazardly in the diachronic development of a language, but that a language adds basic color terms in a particular order, which is interpreted as an evolutionary sequence: Stage I: black, white Stage II: black, white, red Stage IIIa: black, white, red, green Stage IIIb: black white, red, yellow Stage IV: black, white, red, yellow, green Stage V: black, white, red, yellow, green, blue Stage VI: black, white, red, yellow, green, blue, brown Stage VII: black, white, red, green, yellow, blue, brown, purple, pink, orange, grey. Since the publication of Berlin and Kay’s study, there has been some elaboration and criticism of their conclusions, and in response to these, the two linguist-anthropologists have modifi ed them. In 1975, Orð og tunga 15 (2013), 141–161. © Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum, Reykjavík. ttunga_15.indbunga_15.indb 141141 116.4.20136.4.2013 111:58:501:58:50 142 Orð og tunga Brent Berlin and Elois Ann Berlin introduced a light-warm versus dark-cool stage instead of the earlier categorization based on bright- ness contrast. -

On the Receiving End the Role of Scholarship, Memory, and Genre in Constructing Ljósvetninga Saga

On the Receiving End The Role of Scholarship, Memory, and Genre in Constructing Ljósvetninga saga Yoav Tirosh Dissertation towards the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Iceland School of Humanities Faculty of Icelandic and Comparative Cultural Studies October 2019 Íslensku- og menningardeild Háskóla Íslands hefur metið ritgerð þessa hæfa til varnar við doktorspróf í íslenskum bókmenntum Reykjavík, 21. ágúst 2019 Torfi Tulinius deildarforseti The Faculty of Icelandic and Comparative Cultural Studies at the University of Iceland has declared this dissertation eligible for a defence leading to a Ph.D. degree in Icelandic Literature Doctoral Committee: Ármann Jakobsson, supervisor Pernille Hermann Svanhildur Óskarsdóttir On the Receiving End © Yoav Tirosh Reykjavik 2019 Dissertation for a doctoral degree at the University of Iceland. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the author. ISBN 978-9935-9491-2-7 Printing: Háskólaprent Contents Abstract v Útdráttur vii Acknowledgements ix Prologue: Lentils and Lenses—Intent, Audience, and Genre 1 1. Introduction 5 1.1 Ljósvetninga saga’s Plot in the A-redaction and C-redaction 6 1.2 How to Approach Ljósvetninga saga 8 1.2.1 How to Approach This Thesis 9 1.2.2 Material Philology 13 1.2.3 Authorship and Intentionality 16 1.3 The Manuscripts 20 1.3.1 AM 561 4to 21 1.3.2 AM 162 C fol. 26 2. The Part About the Critics 51 2.1 The Debate on Ljósvetninga saga’s Origins in Nineteenth- and Twentieth- Century Scholarship 52 2.1.1 Early Discussion of Ljósvetninga saga: A Compilation of Loosely Connected Episodes 52 2.1.2 Þáttr theory 54 2.1.3 Freeprose and Ljósvetninga saga as a “Unique” Example of Oral Variance: The Primacy of the C-redaction 57 2.1.4 Bookprose and Ljósvetninga saga as a Misrepresented and Authored Text: The Primacy of the A-redaction 62 2.1.5 The Oral vs. -

Article This Article Focuses on the Icelandic Lexis' History by Analysing the Loanwords of Latin Origin in It

On Loanwords of Latin Origin in Contemporary Icelandic by Matteo Tarsi Category: Article This article focuses on the Icelandic lexis' history by analysing the loanwords of Latin origin in it. The corpus examined traverses the history of Icelandic through its whole. The borrowings are divided into four main waves, excluding the preliterary period. Each wave is dominated by one or two borrowing languages. The semantic fields Icelandic selects loanwords from are various and no field is strictly bound to any of the four waves above mentioned. Finally some words of particular interest are presented and discussed, for the importance they assume in the light of the Icelandic lexis' history. I. Introduction Although the consensus in the field of modern Icelandic linguistics attributes relatively little foreign influence on the national language claiming that the Icelandic vocabulary tends toward the rejection of loanwords (cf. KVARAN 2004a,b), several studies have pointed out that such influences have always been present and that Icelandic is not to be considered an isolated or pure North Germanic language (see FISCHER, ÓSKARSSON, WESTERGÅRDNIELSEN among others), not even at its oldest stage. In my research I have collected what I consider to be a large majority of the Icelandic loanwords that have their roots, either directly or indirectly, in Latin (although they may as well be loanwords there already) and are still used in the language (see TARSI). Latin has been chosen due to the fact that such a corpus pervades the Icelandic lexis, especially from a semantic point of view, and makes it actually possible to have a broad view of it since borrowings of Latin origin come from very different directions which also happen to be the main sources Icelandic borrowed words from during the centuries (cf. -

The Proverbial Heart of Hrafnkels Saga Freysgoða: “Mér Þykkir Þar Heimskum Manni at Duga, Sem Þú Ert.”

The Proverbial Heart of Hrafnkels saga Freysgoða: “Mér þykkir þar heimskum manni at duga, sem þú ert.” RICHARD L. HARRIS ABSTRACT: This essay considers the thematic force of a proverbial allusion in Hrafnkels saga when the political dilettante Sámr Bjarnason reluctantly agrees to help his uncle Þorbjǫrn seek redress for the killing of his son by Hrafnkell Freysgoði. “Mér þykkir þar heimskum manni at duga, sem þú ert” [I want you to know that in my opinion I am helping a fool in helping you], he comments, alluding to the traditional proverb Illt er heimskum lið at veita [It’s bad to give help to the foolish] setting one theme of this short but complex and much studied narrative. Examination of the story suggests that nearly all of its characters behave with varying degrees of foolishness. Further, it can be seen that Sámr’s foolishness dictates his fall after defeating Hrafnkell in legal proceedings and that, conversely, Hrafnkell’s rehabilitation is the result of correcting that unwise social behaviour which led to his initial defeat. RÉSUMÉ: Cet article examine la force thématique derrière une phrase proverbiale trouvée dans l’œuvre Hrafnkels saga. Lorsqu’un dilettante politique, Sámr Bjarnason, accepte à contrecoeur d’aider son oncle, Þorbjǫrn, à obtenir réparation pour le meurtre de son fils aux mains de Hrafnkell Freysgoði, il déclare, « Mér þykkir þar heimskum manni at duga, sem þú ert » [je veux que vous sachiez que, selon moi, j’aide un abruti en vous aidant]. Son commentaire fait allusion au proverbe traditionnel, Illt er heimskum lið at veita [il est mal d’offrir de l’aide à un sot]. -

Power and Political Communication. Feasting and Gift Giving in Medieval Iceland

Power and Political Communication. Feasting and Gift Giving in Medieval Iceland By Vidar Palsson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor John Lindow, Co-chair Professor Thomas A. Brady Jr., Co-chair Professor Maureen C. Miller Professor Carol J. Clover Fall 2010 Abstract Power and Political Communication. Feasting and Gift Giving in Medieval Iceland By Vidar Palsson Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor John Lindow, Co-chair Professor Thomas A. Brady Jr., Co-chair The present study has a double primary aim. Firstly, it seeks to analyze the sociopolitical functionality of feasting and gift giving as modes of political communication in later twelfth- and thirteenth-century Iceland, primarily but not exclusively through its secular prose narratives. Secondly, it aims to place that functionality within the larger framework of the power and politics that shape its applications and perception. Feasts and gifts established friendships. Unlike modern friendship, its medieval namesake was anything but a free and spontaneous practice, and neither were its primary modes and media of expression. None of these elements were the casual business of just anyone. The argumentative structure of the present study aims roughly to correspond to the preliminary and general historiographical sketch with which it opens: while duly emphasizing the contractual functions of demonstrative action, the backbone of traditional scholarship, it also highlights its framework of power, subjectivity, limitations, and ultimate ambiguity, as more recent studies have justifiably urged. -

When Fuck Met Fokk in Icelandic

Two loanwords meet: when fuck met fokk in icelandic by Veturliði Óskarsson Icelandic phonotactics and phonology require the short vowels /ʌ/ and /ə/ in English loanwords be represented by the phoneme /œ/. The words fuck and fucking, which began appearing in Icelandic around 1970, are however nearly always pronounced and spelt differently from what is expected, i.e. with the vowel ɔ[ ] and spelt ‘fokk’, ‘fokking’. The reason is that there already existed in Icelandic a couple of older loan- words, probably from Danish, which to some extent both in terms of semantics and pronunciation already occupied the position that the new loanwords were expected to take in the language. This article discusses the meaning of the older loanwords, their use and semantic development, and compares them to the newer words, with examples taken to show what happens when the new loanwords met the old ones. 1. Introduction In the last few decades, the English words fuck and fucking have become part of the Icelandic language1. They began showing up sporadically in Icelandic newspapers and magazines around 1970 – very few examples are older than that – but it was not until the 1980s and the beginning of the twenty-first century that fuck and fucking respectively became frequent. Their surface forms in Icelandic today are fokk (noun/interjection), fokka (verb) and fokking (adverb/interjection). It is not at all surprising that these words have found their way into Icelandic, widespread as they are in modern pop culture, music and films, which – as in other European countries – are primarily influenced by English in Iceland.2 When loanwords enter a language, certain things happen.