Denise C. Decoste, Ed. D., OTR 2 Decoste Writing Protocol Decoste WRITING Protocol Evidence-Based Research to Make Instructional and Accommodation Decisions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SDC Books Jun2010 Updated Jan2012

Société des calligraphes de Montréal Livres - Books Livres qui appartiennent à la Société des calligraphes de Montréal. La majorité a été donnée à la Société par Mme Fred Felsky et Mme Eddie Prévost en mémoire de leurs époux. Les commentaires ont été rédigés par d’anciens membres de la Société (anglophones). Books belonging to the Société des Calligraphes de Montréal. Most were given to the Société by Mrs. Fred Fesky and Mrs. Eddie Prévost, in memory of their husbands. All comments were written by past members of the Society. Note: Vivien Lappa et Saskia Latendresse ont révisé la liste en 2010; les titres en rouge sont ceux dont la Société pourrait se départir. Les livres achetés par la Société en 2011 ont été ajoutés. Auteur / Author Titre / Title Éditeur, ville / Publisher, City Année de publication / Nombre de pages / Description Langue / Publication year Number of pages Language - Calligrapher's Handbook, New Burlington Books, London 1987 English The AARON, W.M. Italic Writing: A Concise Alec Tiranti, London 1971 110 pages A complete guide to learning Italic from materials through English Guide letterforms to cursive. Good-looking calligraphy examples throughout with some interesting letter-combination exercises. A useful alternative for learning or improving your Italic. (K. Poulsen) ALEXANDER, J.J.G. Decorated letter, The Thames & Hudson, London 1978 The Decorated Letter is a sketchy but scholarly discussion English of some of the decorated letters to be found in European manuscripts from the 4th to 15th Centuries. There are forty excellent coloured reproductions of initial letters from the Lindesfarne Gospels to Miroir de la Salvation Humaine by Jean Mielot (1448-49). -

Escribiente Library Books

Escribiente Library Books Escribiente Library Books * UPDATED 2/4/2016 GENRE Author/Publisher Title Date # of Copies Deposit Color description Required Calligraphy Tutorials General A Quill Book Calligrapher’s Handbook, The 1985 1 heavily illustrated, introduction to various styles, some history Calligraphy - Italic Adams, Caroline Joy An Italic Calligraphy Handbook (Dover) 2004 (1985) 1 Italics History, tool, lowercase and caps, variations & swashes History of Calligraphy Anderson, Donald Art of Written Letters, The 1969 1 Classic: From Romans to 20th Century + Greek/Arabic/Chinese Illumination Angel, Marie Painting for Calligraphers 1984 1 includes color theory, design, botanical, heraldry, painting on vellum Illumination Backhouse, Janet Illuminated Manuscript, The 1979 HC 1 70 manuscripts represented (color and b&w), covering 900 years. Illumination Backhouse, Janet Lindisfarne Gospels 1992 1 Illumination Bain, George Celtic Art - The Methods of Construction (Dover) 1973 1 Calligraphic - Art & Artists Baker, Arthur Calligraphic Alphabets 1974 1 plates of various alphabets (no instruction) Calligraphic - Art & Artists Baker, Arthur Calligraphic Art of Arthur Baker, The 1983 1 plates of various alphabets (no instruction) Calligraphic - Art & Artists Baker, Arthur Calligraphy 1973 1 plates of various alphabets (no instruction) Calligraphy - Celtic/Uncial Baker, Arthur Celtic Hand: Stroke by Stroke (Dover) 1983 1 very detailed illustrations of Uncial A-Z, with pen manipulation Calligraphic - Art & Artists Baker, Arthur Dance of the Pen 1978 1 text and texture, abstract (no instruction) Calligraphic - Art & Artists Baker, Arthur Script Alphabet, The 1978 1 variations on italic, plates of various alphabets (no instruction) Illumination Barbara Miodonska Pulawska, Kolekcja… (Illumination in Books) 2001 1 PB Text is in Polish. -

Spring 2011 Supplying Calligraphers, Lettering Artists, Illuminators

spring 2011 Supplying calligraphers, lettering artists, illuminators, bookbinders and papercraft enthusiasts worldwide with books, tools, and materials since 1981. 61 5 64 50 61 61 ORDER NOW! toll free: 800-369-9598 v web: www.JohnNealBooks.com Julie Eastman. B&L 8.2 “...an informative, engaging, Bill Waddington. B&L 8.2 and valued resource.” Need something new to inspire you? –Ed Hutchins Subscribe to Bound & Lettered and have each issue – filled with practical information on artists’ books, bookbinding, calligraphy and papercraft – delivered to your mailbox. Bound & Lettered features: how-to articles with helpful step-by-step instructions and illustrations, artist galleries featuring the works of accomplished calligraphers & book artists, useful articles on tools & materials, and book & exhibit reviews. You will find each issue filled with wonderful ideas and projects. Subscribe today! Annie Cicale. B&L 8.3 Every issue of Bound & Lettered has articles full of practical information for calligraphers, bookbinders and book artists. Fran Watson. B&L 8.3 Founded by Shereen LaPlantz, Bound & Lettered is a quarterly magazine of calligraphy, bookbinding and papercraft. Published by John Neal, Bookseller. Now with 18 color pages! Subscription prices: USA Canada Others Four issues (1 year) $26 $34 USD $40 USD Eight issues (2 years) $47 $63 USD $75 USD 12 issues (3 years) $63 $87 USD $105 USD mail to: Bound & Lettered, 1833 Spring Garden St., First Floor, Sue Bleiwess. B&L 8.2 Greensboro, NC 27403 b SUBSCRIBE ONLINE AT WWW .JOHNNEALBOOKS .COM B3310. Alphabeasties and Other Amazing Types by Sharon Werner and Sarah Forss. 2009. 56pp. 9"x11.5". -

George Bickhams Penmanship Made Easy Or the Young Clerks Assistant Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GEORGE BICKHAMS PENMANSHIP MADE EASY OR THE YOUNG CLERKS ASSISTANT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George Bickham | 64 pages | 21 Jan 1998 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486297798 | English | New York, United States George Bickhams Penmanship Made Easy or the Young Clerks Assistant PDF Book Illustration Art. Add links. Learning to write Spencerian script. George Bickham the Elder was born near the end of the seventeenth century. July 13, at am. For what was meant to be a practical form of business handwriting, the round-hand scripts displayed in The Universal Penman feature a surprising number of flamboyant flourishes and decorative extensions. A complete volume of The Universal Penman published in London in might cost a few thousand dollars or more. Folio , detail. Prints and Multiples. American Fine Art. This was the work of George Bickham, a calligrapher and engraver who in took on the task of inviting the best scribes of his day to contribute examples of their finest handwriting, which would be engraved, published, and sold to subscribers as a series of 52 parts over a period of eight years. Collecting The specimen illustrates the beautiful flowing shaded letterforms based on ovals that typify this style of script. In the 18th century, writing masters taught handwriting to educated men and women, especially to men who would be expected to use it on a daily basis in commerce. Kelchner, He is Director of the Scripta Typographic Institute. A wonderful example of this script, penned by master penman HP Behrensmeyer is shown in Sample 4. Studio handbook : lettering : over pages, lettering, design and layouts, new alphabets. -

Escribiente Library Master V19 Nov-2019

Escribiente Library Books Escribiente Library Books * updated November 2019 GENRE Author/Publisher Title Date # of Copies Deposit Color description Required Calligraphy Tutorials General A Quill Book Calligrapher’s Handbook, The 1985 1 heavily illustrated, introduction to various styles, some history History of Calligraphy Anderson, Donald Art of Written Letters, The 1969 1 Classic: From Romans to 20th Century + Greek/Arabic/Chinese Art & Exhibitions Angel, Marie The Twentythird Palm: King James Version 1970 1 HC Illustrations of nature, with text in Roman Caps Illumination Angel, Marie Painting for Calligraphers 1984 1 includes color theory, design, botanical, heraldry, painting on vellum Calligraphy - Copperplate/PP Antonio, Paul Copperplate Script - A Yin & Yang Approach 2018 1 History of Calligraphy Arrighi, Tagliente, Palatino Three Classics of Italian Calligraphy 1953 1 PB Dover. All images with exception of Introduction by Oscar Ogg. quotes from an artist/calligrapher’s collection on Philosophy, Art, Family Creativity Ayers, Gay Unlocking The Words - A Book of Quotes 2016 1 PB and Friendship, Travel, Creativity, Poetry, Nature, and more Illumination Backhouse, Janet Illuminated Manuscript, The 1979 HC 1 70 manuscripts represented (color and b&w), covering 900 years. Illumination Backhouse, Janet Lindisfarne Gospels 1992 1 Illumination Bain, George Celtic Art - The Methods of Construction (Dover) 1973 1 Art & Exhibitions Baker, Arthur Calligraphic Alphabets 1974 1 plates of various alphabets (no instruction) Art & Exhibitions Baker, -

Reed Elizabeth Final Thesis Redacted.Pdf

Writing by Hand - A Journey of Creative Self Discovery Author Reed, Elizabeth M Published 2021-05-06 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/4189 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/404466 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au WRITING BY HAND—A JOURNEY OF CREATIVE SELF DISCOVERY Elizabeth (Libbi) Reed Bachelor of Digital Media with Honours Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts Queensland College of Art Arts Education Law Griffith University Submitted: November 2020 KEYWORDS Calligraphy, creative block, creative identity, daily habit, decision making, hand lettering, journaling, memory, motor skills, self-development, self-talk, sensemaking, sketchnotes, typography. i ABSTRACT This research addresses the core objectives surrounding the action of writing by hand. It responds to the overuse of digital technologies which have led to a lack of everyday handwriting. The introduction of sketchnotes introduces an opportunity to explore and build handwriting skills as an everyday practice. Sketchnotes create the hand-to-brain connection. This exegesis outlines how the problem of deteriorating fine motor skills is addressed through a series of creative projects in which methodical and strategic exercises including repetition, play, and experimentation centre on the actions of writing by hand. The practice-based research consists of a multi-faceted creative exploration, experimenting with long-established traditional calligraphic study, and with newer technologies such as Virtual Reality (VR). I argue that building writing by hand skills strengthens creative expression, resulting in increased confidence. -

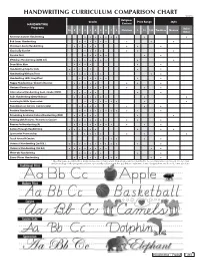

Handwriting Curriculum Comparison Chart

HANDWRITING CURRICULUM COMPARISON CHART ©2018 Religious Grades Price Range Style HANDWRITING Content Programs Italic/ PK K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Christian $ $$ $$$ Tradition Modern Other American Cursive Handwriting • • • • • • • • • Bob Jones Handwriting • • • • • • • • • Christian Liberty Handwriting • • • • • • • • Classically Cursive • • • • • • • Cursive First • • • • • • • D'Nealian Handwriting (2008 ed.) • • • • • • • • • Draw Write Now • • • • • • Handwriting Help for Kids • • • • • • • Handwriting Without Tears • • • • • • • • • Handwriting Skills Simplified • • • • • • • • Happy Handwriting / Cheerful Cursive • • • • • • • • Horizons Penmanship • • • • • • • • • International Handwriting Cont. Stroke (HMH) • • • • • • • Italic Handwriting (Getty-Dubay) • • • • • • • • • Learning to Write Spencerian • • • • • • • • • New American Cursive (cursive only) • • • • • • • Pentime Handwriting • • • • • • • • • • • Preventing Academic Failure Handwriting (PAF) • • • • • • • Printing with Pictures / Pictures in Cursive • • • • • • • • • • Reason for Handwriting (A) • • • • • • • • • • • Sailing Through Handwriting • • • • • • • • • Spencerian Penmanship • • • • • • • Teach Yourself Cursive • • • • • • Universal Handwriting (2nd Ed.) • • • • • • • • • • • • Universal Handwriting (3rd Ed.) • • • • • • • • • • Write-On Handwriting • • • • • • • Zaner-Bloser Handwriting • • • • • • • • • • • *This chart was assembled by Rainbow Resource Curriculum Consultants and is intended to be a comparative tool based on our own understanding of the programs -

Universal Penman Rollerball Nib the J-Form Dip Pen Allography Cursive

eraser An eraser or rubber is an article of stationery that is used for removing pencil and sometimes pen writings. Erasers have a rubbery consistency and are often white or pink, although modern materials allow them to be made in any cursive allography colour. Many pencils are equipped with an eraser on one Cursive is any style end. Typical erasers are made from synthetic rubber, but The letter a is depicted of handwriting that is dip pen more expensive or specialized erasers can also contain vi- fountain pen with two common glyphs nyl, plastic, or gum-like materials. Other, cheaper erasers ballpoint designed for writing A dip or nib pen consists of a metal nib A fountain pen is a nib pen that, unlike its predecessor the dip pen, contains an internal reservoir which differ between can be made out of synthetic soy-based gum. notes and letters quickly with capillary channels mounted on a of water-based liquid ink. From the reservoir, the ink is drawn through a feed to the nib and then typefaces and handwrit- A ballpoint pen has an internal chamber filled with a vis- by hand. In the Arabic, to the paper via a combination of gravity and capillary action. As a result, the typical fountain pen ing styles. Allography cous ink that is dispensed at tip during use by the rolling handle or holder, often made of wood. Latin, and Cyrillic writing Other materials can be used for the requires little or no pressure to write. is this variation in how action of a small metal sphere made of brass, steel or systems, the letters in letters are formed. -

The Pursuit of Penmanship

The Pursuit Of Penmanship © Tancia Ltd 2013 The Pursuit of Penmanship Handwriting and Evolution The ability to communicate in a written form is a relatively new development in our human evolution that began with the development of the cuneiform script in Sumer (now in Southern Iraq) approximately 5,500 years ago. Prior to this humans, relied upon verbal and non-verbal forms of communication and it is understood that hu- mans have been using spoken language for more than 35,000 years. Whereas speech and sight might be seen as innate abilities in humans, writing involves an additional thought process whereby the information that we seek to communicate has to be interpreted and re-communicated using letters or graph- emes to represent the sounds for each word. Written communication is not a pas- sive process but requires our understanding and willingness to take action rather than merely absorb information through listening. Verbal and non-verbal forms of communication are present throughout the animal world, but the evolutionary de- velopment of written communication signalled a significant change in human brain development, as described by Maryanne Wolf in her book, Proust and the Squid: the Story and Science of the Reading Brain; “The brain became a beehive of activity. A network of processes went to work: the visual and visual association areas responded to visual patterns (or representa- tions); frontal, temporal and parietal areas provided information about the smallest sounds in words….; and finally areas in the temporal and parietal lobes processed meaning, function and connections.”1 The First Schools of Writing The development of written communication has traditionally marked the transition in history from ‘prehistoric’ to ‘civilisation’ and this period also saw the development of the first schools. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Lucie Koktavá The History of Cursive Handwriting in the United States of America Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A., Ph. D. 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the sources listed in the bibliography. ....................................................... Lucie Koktavá Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A., Ph.D. for his guidance and advice. I am also grateful for the support of my family and my friends. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 1 The Description of Cursive Handwriting ............................................................. 8 1.1 Copperplate ..................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Spencerian Cursive Writing System ............................................................... 12 1.3 Palmer Method ................................................................................................ 15 1.4 D'Nealian ........................................................................................................ 17 2 The History of American Handwriting ............................................................... 19 2.1 The First Period of American Handwriting (1600–1800) .............................. 20 2.2 The Second Period -

A History of Learning to Write

9 A History of Learning to Write EWAN CLAYTON W I begin with a brief background account of the in the way handwriting is understood. Over the last origins of our present letterforms and how they half-century our knowledge of its history has developed arrived in England. This story has its starting point in in detail but not in perspective; new areas of scholar- Renaissance Italy; the Gothic hands of the Middle ship and technology are now changing that. Recent Ages, their origins in the twelfth century and the studies of the history of reading have opened our eyes Anglo-Saxon, early European and late Roman cursives to the sheer variety of ways in which we read; privately that came before them are a subject in their own right. or in public, skimming, reflectively, slowly and repeat- The focus here is on the sixteenth century, an extra- edly; in church, kitchen, library, train or bed. People ordinary period in which all our contemporary have not always read the same way; reading has a his- concerns about handwriting have their roots. Study tory. Handwriting, too, has a history and is practised of the intervening five centuries challenges the view in an equally rich diversity of ways. We write differ- that there is nothing more to be said than to list ently when we copy notes for revision or annotate writing masters and convey a vague feeling that it was the margins of a report, the handwriting on our tele- downhill all the way. In fact it was. An understanding phone pad is different from that in a letter of sym- of the origins of our present day scripts helps us to pathy or on a birthday card, the draft of a poem or see that the sub-text underlying most discussions on the cheque written at the supermarket checkout is handwriting is our changing definitions of what it is yet again different from the ‘printing’ on our tax to be human. -

Ornamental Penmanship

Dr. Joseph M. Vitolo’s Record of Contributions to the Art & History of Ornamental Penmanship 1 February 26, 2021 Dear friends, I have spent many years searching and documenting the art, techniques and historical information of the pointed pen art form. I proceed in the footsteps of those who came before me that have added greatly to our knowledge base. In 2015, I decided to document, or at least to put into perspective my own contributions to the pointed pen art form. The result of that effort was this document. While these pages do not contain a complete list, they do represent the majority of my efforts on behalf of Ornamental Penmanship and the pointed pen art form in general. It is my hope that this document will serve as a roadmap to those seeking this information in cyberspace. It gives me great satisfaction to know that pen artists around the globe now know the art and contribution of penmen such as Lupfer, Madarasz and Zaner. I am convinced that the spark many of us have seeded over the years has now become a raging fire. I am often asked, “Why do you give it all away?” The answer is very simple. I was a novice once too and it is my way of repaying the extraordinary kindness and generosity that I was shown at my first IAMPETH Convention way back in 1999. The quote of Pablo Picasso on page 3 of this document best sums up my thoughts on this matter. All I ask in return from anyone that has enjoyed/benefitted from the materials I provided is that you ‘Pay it Forward’ if you get the chance to help someone who is struggling in calligraphy or in life.