Intervening in Stress, Attachment and Challenging Behaviour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Nordmark Im Glaubenskampf Eine Antwort Der Kirche an Gustav

Die Nordmark im Glaubenskampf Eine Antwort der Kirche an Gustav Frenssen Herausgegeben von Johannes Lorentzen Pastor in Kiel [1936] Verlag: Missionsbuchhandlung Breklum [1] Druck: Missionsbuchhandlung Breklum. [2] Inhalt Johannes Lorentzen: Vorwort ................................................................................................................. 2 Otto Dibelius: Frenssens Abschied vom Christentum ............................................................................. 2 Johannes Tonnesen: Die Wandelbarkeit Gustav Frenssens .................................................................... 7 Johannes Lorentzen: Gustav Frenssens Christusbild ............................................................................ 11 Wolfgang Miether: Frenssens Gottesbotschaft ..................................................................................... 16 Hans Dunker: Die Verschwommenheit des heidnischen Glaubens – Die Klarheit des christlichen Glaubens ................................................................................................................................................ 20 Hans Treplin: Anmerkungen zum ersten Psalm .................................................................................... 23 Frau Tonnesen: An Gustav Frenssen. Das Wort einer Mutter aus der Nordmark ................................. 28 Heinrich Voß: Um die Jugend der Nordmark. Wort eines Lehrers ....................................................... 32 Johannes Tramsen: Frenssens Urteil über die Kirche der Nordmark und -

Der Skatfreund Nr

Die Zeitschrift des Deutschen Skatverbandes Der Skatfreund Nr. 4 August/September 53. Deutsche Einzelmeisterschaften Braunlage 3. Skatolympiade Altenburg/Thüringen $EUTSCHLANDPOKAL V ÌÀ>ÕV iÀÛiÀ>ÃÌ>ÌÕ} ÊÓΰÊÕ}ÕÃÌÊÓäänÊÊ`iÊiÃÃi >iÊ£ÊÕ`ÊÓÊÊ ÀiÃ`iÊiÃÃiÀ}ÊÈ]Êä£äÈÇÊ ÀiÃ`i® "vviiÊ6iÀ>ÃÌ>ÌÕ}ÊqÊÌ}i`ÃV >vÌÊÊiiÊ6iÀiÊÃÌÊV ÌÊiÀvÀ`iÀV -V À iÀÀ\Ê Ê ÀÊLiÀÌ]Ê ØÀ}iÀiÃÌiÀÊvØÀÊ7ÀÌÃV >vÌÊ`iÀÊ-Ì>`ÌÊ ÀiÃ`i° 6iÀ>ÃÌ>ÌiÀ\Ê iÕÌÃV iÀÊ->ÌÛiÀL>`Êi°6° ÕÃÀV ÌiÀ\Ê Ê -BV ÃÃV iÀÊ->ÌÛiÀL>`ÊÊ6iÀL>`Ã}ÀÕ««iÊ ÀiÃ`iÊi°6° /ÕÀiÀiÌÕ}\Ê *ÀBÃ`ÕÊ`iÃÊ -6° -V i`ÃÀV ÌiÀ\Ê Ì}i`iÀÊ`iÃÊ iÕÌÃV iÊ->Ì}iÀV Ìð ÕÀÀiâi\Ê âi]Ê/>`iÊÕ`ÊÝi`7iÀÌÕ}° /ii iÀ\Ê Ê iÊ/ii iÀâ> ÊÃÌÊ>ÕvÊ£°{ääÊLi}ÀiâÌtÊ1ÊvÀØ âiÌ}iÊi`Õ}ÊÜÀ`Ê}iLiÌi° `>ÌBÌi\Ê ÎÊ-iÀiÊDÊ{nÊ-«ii]Ê`iÊΰÊ-iÀiÊÜÀ`Ê}iÃiÌâÌ]Ê<iÌÌÊiÊ-iÀiÊÓÊ-ÌÕ`i] ÊÊ Ê Ê />`iÊÕ`ÊÝi`7iÀÌÕ}ÊÕÀÊvØÀÊ-iÀiÊ£ÊÕ`ÊÓ° -«iLi}\ÊÊ ->ÃÌ>}]ÊÓΰÊÕ}ÕÃÌÊÓäänÊÕÊ£ä\ääÊ1 ÀÊ >ÃÃ\Ê>LÊän\ääÊ1 À®° -Ì>ÀÌ}i`\Ê Ê âi\Ê£x]ääÊEÊ°Ê>ÀÌi}i`ÊLiÊ6À>i`Õ}Ê>Ê-«iÌ>}Ê£n]ääÊE®° ÊÊÊ Ê Ê />`iÊÕ`ÊÝi`ÊiÊ-«iiÀÊ£ä]ääÊ° 6iÀÀiiÊ-«ii\Ê ÛÊ-«iÊ£ÊqÊÎÊiÜiÃÊä]xäÊE]Ê>LÊ`iÊ{°Ê-«iÊiÊ£]ääÊE° -Ì>ÀÌ>ÀÌiÊÊ ÀiÌ>}]ÊÓÓ°ÊÕ}ÕÃÌÊ>LÊ£Ç\ääÊ1 ÀÊâÕÊ6ÀÌÕÀiÀ° >ÕÃ}>Li\Ê Ê ->ÃÌ>}]ÊÓΰÊÕ}ÕÃÌÊÛÊän\ääÊ1 ÀÊLÃÊä\ÎäÊ1 À° i`Õ}\ÊÊ i`iÃV ÕÃÃÊLÃʣȰÊÕ}ÕÃÌÊÓääntÊ iÀØVÃV Ì}Õ}Ê>V ÊLiâ> ÌiÀÊÕ`ÊÃV ÀvÌÊ Ê Ê Ê V iÀÊi`Õ}ÊLiÊ -6°Ê/>}iÃ>i`Õ}Ê âiÜiÌÌLiÜiÀL®ÊÕÀÊLÃÊä\ÎäÊ1 À Ê Ê Ê ÛÀÊ"ÀÌ]ÊÃÜiÌÊV ÊvÀiiÊ*BÌâiÊÛÀ >`iÊÃ`ÊâÕÊ*ÀiÃÊÛÊ£n]ääÊE° Ê Ê Ê i`Õ}iÊÕ`Ê â> Õ}iÊiÀv}iÊLi\ ÊÊÊÊ ÕLiÀÌÊ7>V i`Àv]ÊÕ«iÜi}ÊÇ]ÊxÎn{äÊ/ÀÃ`Àv] Ê Ê Ê >\Ê ÕLiÀÌÜ>V i`ÀvJÌi°`i° Ê Ê Ê >ÛiÀL`Õ}\ Ê Ê Ê -6ÊqÊ *Ê ÀiÃ`i]ÊÌÊ{äÊ£ÈÊäxÊÎäÊx]Ê Ê Ê Ê <ÊnÎäÊÈx{Êän]Ê6,Ê >ÊÌiLÕÀ}iÀÊ>` Ê Ê Ê iÊ`ÀiÌiÊi`Õ}ÊiÀv}ÌÊÕÌiÀÊÜÜÜ°`«Óään°`ÃÛ°`i -

The Rules of Bonken • Bonken Consists of 13 Separate Games, 8 Minus Games and 5 Plus Games

The rules of Bonken • Bonken consists of 13 separate games, 8 minus games and 5 plus games. With every game a different number of points can be earned. The way these points can be earned is different for different games. The so-called minus games yield minus points and plus games yield plus points. There are as many plus points as there are minus points, so that the total number of points of all players is zero. The objective of the game is to get as many points as possible. In a bonk session 12 games will be played, and every game only once. Everybody is obliged to play a plus game once, and only once. Therefore 1 plus game will never be played. • Bonken is played with 52 cards. 13 cards per suit (Spades, Hearts, Diamonds and Clubs). The order of the cards for all the games from low to high is: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, jack, queen, king, ace. • One person deals the cards. The person who sits opposite the dealer chooses the game. The person on the left of the chooser starts bidding (see below). And the person on the right of the chooserleads.Theveryfirstgame,though,ischosenbythepersonwhohas the seven of spades in his hand. Each player has to follow suit when possible (for the domino game see below). The person who wins the trick leads next. After every game we rotate clockwise forthenextdealer,chooser,bidderandthepersonwholeadsfirst. Towards the end of the game, it could be that a chooser is passed. This situation occurs when all minus games have been played and the chooser has already chosen a plus game. -

EPOU 08 0763J BW Dokter Voor Het Volk DEF.Indd

Dokter van het volk Bij EPO verschenen ook: Dokter in overall Karel Van Bever De cholesteroloorlog. Waarom geneesmiddelen zo duur zijn Dirk Van Duppen De kopervreters. De geschiedenis van de zinkarbeiders in de Noorderkempen Staf Henderickx Wiens Belang? Het Vlaams Belang over inkomen, werk, pensioenen Norbert Van Overloop Een kwarteeuw Mei 68 Ludo Martens en Kris Merckx KRIS MERCKX DOKTER VAN HET VOLK Omslagontwerp: Compagnie Paul Verrept Foto cover: © Thierry Strickaert Foto achterfl ap: © [email protected] Linografi eën titelbladzijden delen: © Marc Jambers Kaart p.350-351: © Lusn Van Den Heede Vormgeving: EPO Druk: drukkerij EPO © Kris Merckx en uitgeverij EPO vzw, 2008 Lange Pastoorstraat 25-27, 2600 Berchem Tel: 32 (0)3 239 68 74 Fax: 32 (0)3 218 46 04 E-mail: [email protected] www.epo.be Geneeskunde voor het Volk www.gvhv.be Isbn 978 90 6445 497 4 D 2008/2204/19 Nur 740 Verspreiding voor Nederland Centraal Boekhuis BV Culemborg De uitgever zocht vergeefs naar de houders van het copyright van sommi- ge illustraties in dit boek. Personen of instellingen die daarop aanspraak maken, kunnen contact opnemen met de uitgever. Inhoud Dankwoord 9 Deel 1. Een nieuwe wind 13 1. De wieg van Geneeskunde voor het Volk 15 Na mei ’68: de daad bij het woord 15 Naar de mijncités 19 De scheepsbouwers van Cockerill Yards, hun vrouwen en onze wieg 22 2. Gratis en kwaliteit gaan samen 30 Werken aan terugbetalingstarieven 30 Kwaliteit leveren 55 3. Geneeskunde en politiek engagement 72 Ziekte en dood vanuit mondiaal perspectief 72 Kan een arts alleen maar wonden helen? 77 Twee dokters die ons inspireerden 87 Deel 2. -

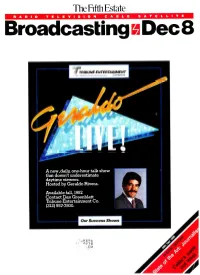

Broadcasting Dec 8

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting Dec 8 ff TRIBUNE ENTERTAINMENT Company A new, daily, one -hour talk show that doesn't underestimate daytime viewers. Hosted by Geraldo Rivera. Available fall, 1987. Contact Dan Greenblatt Tribune Entertainment Co. (212) 557 -7800. Our Success Shows I Jrt.16MXyh Ilr CNN TELEVISION T NORTH BY NORTHWEST T POLTERGEIST SINGIN'IN THE RAI e've combined the Turner Program Our new product list features Services product ... CNN Television, zling array of almost 4,000 films from our the great Cousteau specials, the Color MGM, Warner Brothers and RKO libraries. Classic Network ...with our extensive ac- Packed with great titles and all with the star quisitions from MGM to form one of the power that makes them a virtual Who's most aggressive programming companies Who list in the movie industry. Plus an un- in industry. k. the TPS1 19NFi paralleled collection of theatrical cartoons Services. vision entertainment. GONE `WITH THE WIND TURNER P NETWORK COLOR CLASSIC B1 S ISLAND TURNER PROG GILLIG T OF AMERICA TURNER PRO pORT :1MELIA TURNER PROGRAM SERVI THING :11O"I TURNER PROGRAM SERVICES HIGH SOCIETY GEOGRAPHIC "ON ASSIG ENT" NATIONAL PROGRAM ROCKY ROAD TURNER SERVICES POPEYE TURNER PROGRAM SERVIC I , WHERE E ES DARE TURNER GRAM S like Tom & Jerry, Popeye and Bugs Bunny. ning. Turner Program Services is staffed by Thousands of hours of proven series hits the finest sales and service people in the like Gilligan's Island and CHiPS. -

Cada Fights Firing

SEPTEMBER 3, 1993 VOLUME 22 NUMBER 36 islancc: 3 SECTIONS, 44 PAGES REPui-i SANiBBL AND CAPTIVA, FLORIDA Cada fights firing By MaryJeanne McAward Staff Writer 'f-'':'~-7.' '•'J^T~^'': A former Sanibel police officer, terminated in July for alleged breach of security, is trying to win his job back. According to Sanibel City Attorney Robert Pritt, former officer Brent Cada filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the 20th Judicial Circuit Court. Not an appeal, the writ challenges the termi- nation and requests Cada be reinstated as a police officer. It also includes a judgement for back pay, attorney's fees and other related fees. FAREWELL TO SUMMER: Thousands of weekend. Labor Day traditionally marks Both attorney Harry Blair of Fort Myers, who boaters, anglers and beachgoers will be the end of summer and hopefully, the •please see page 2A enjoying the islands and the water this weather will cooperate with outdoor plans. Gulf Pines residents oppose mandatory fee By Ralf Kircher are opposing a $300 legal fee the results were totaled. How can you say that [legal action] Staff Writer imposed upon them by the Gulf "I was very much dismayed to is going to be beneficial?" the resi- ix Gulf Pines property owners Pines Property Owners Association. learn that Gulf Pines property own- dent asked. "It bothered me [that The fee will go toward the associ- ers voted 84-6 in favor of pursuing the association] said to send a ation court battle against the City legal action against the city," said check immediately; that they had of Sanibel's proposed Tarpon Bay Old Banyan Way resident Barbara already incurred expenses before Weir Project. -

Die Entwicklung Der Urindogermanischen Nasalpräsentien Im Germanischen

Zentrum historische prachwissenschaften www.sprachwiss.lmu.de S http://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/ Mubahis Münchener Beiträge zur Allgemeinen und Historischen Sprachwissenschaft herausgegeben von Peter-Arnold Mumm Institut für Vergleichende und Indogermanische Sprachwissenschaft sowie Albanologie Wolfgang Schulze Institut für Allgemeine und Typologische Sprachwissenschaft Band 2 Corinna Scheungraber Die Entwicklung der urindogermanischen Nasalpräsentien im Germanischen 2010 Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Institut für Vergleichende und Indogermanische Sprachwissenschaft DDieie Entwicklung der urindogermanischen Nasalpräsentien im Germanischen Hausarbeit zur Erlangung des Magistergrades an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München vorgelegt von Corinna Scheungraber München, den 01. April 2010 Hauptreferent: Dr. habil. E. Hill Koreferent: Dr. habil. P.-A. Mumm ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ I N H A L T S V E R Z E I C H N I S 1.0 Einleitung und Zielsetzung der Arbeit ..................................................................................... S. 6 1.1 Forschungsgeschichte der idg. Nasalpräsentien ...................................................... S. 7 1.2 Uridg. Nasalinfix vs. einzelsprachliches Nasalsuffix .............................................. S. 14 2.0 Das Material ................................................................................................................................ -

DE KRACHT VAN HET WOORD. De Barok Van Benedetto Croce in Het

Universiteit Gent Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Masterproef geschiedenis 2008-2009 DE KRACHT VAN HET WOORD. De Barok van Benedetto Croce in het licht van het Contrareformatie versus katholieke Reformatie debat. Joris R. Pinseel 20034467 Laat de stilte voor wat ze is… i Inhoud Inhoud. ii Voorwoord. iii Abstract en scriptieverslag v Verklaring i.v.m. de raadpleging van de scriptie. vii 1. Inleidende Casus: De Kaas en de Wormen. 1 2. Het Contrareformatie versus katholieke Reformatie debat. 12 2.1. A Rose still smells as sweet? 12 2.2. Een overzicht. 21 2.3. Van Hubert von Jedin tot John W. O’Malley S.J. 27 2.4. De Nederlanden. 32 2.5. Conclusie. 36 3. Een Babelse historiografie. 39 4. Methodologie. 52 4.1. Een microgeschiedenis. 52 4.2. Een theoretische microgeschiedenis. 60 4.3. Een theoretische microgeschiedenis in de hermeneutische traditie. 68 4.4. Een breder theoretisch kader. 73 5. Toe-eigening. 81 5.1. Toe-eigening door de zwakke. 86 5.2. Toe-eigening door de machtige. 89 6. De Casus Mussolini-Croce: De Barok. 93 6.1. De Risorgimento (1870-1924). 101 6.2. Het monsterverbond (1924-1929). 119 6.3. De slotperiode van Mussolini’s toe-eigening (1930-1943). 128 7. Conclusie. 134 7.1. De Italiaanse connectie. 134 7.2. Croce’s zoektocht naar waarachtige poëzie. 137 7.3. All history is contemporary? 141 7.4. Een probatio pennae . 145 8. Repertorium. 155 ii Voorwoord Waartoe dient dat, een voorwoord? Ik denk dat het een vehikel is dat niemand ooit leest en dient om de juiste mensen te bedanken voor hun inzet, die het voltooien van een of ander werk mogelijk maakte. -

The GAO Journal, No. 15, Spring/Summer 1992

THEG·A·O 1'17027 -1'I70~b AQUARTERLY SPONSORED BY THE U.S. GENERAL ACCOUNTING OffICE • OURNAL SAFE AND SOUND s-rilIg""fr*n 1I/_IPrg RISKY BUSINESS U""" ghg"" SttIffrmJsIIIdttt1 IofItI JhOfl- GOING STALE? 1M.cd , f foodsofrt! sy.- IIUIIlER 15 • SPRNG/su.MR 1992 THEG·A·O _15 AQUARTERlY SPONSORED BY THE U.S. GENERAl ACCOUNTING OffiCE SPRNGISlNMER 1992 OURNAL c o N T E N T s • GIRDING FOR COMPETITION 3 - ~\'ltPI", Croig A. Si",,,,o,,s a"tI C. Sera;", 1't70z.8 • COMMERCIAL BANKING IN THE UNITEDSTATES: A LOOK BACK AND A LOOK AHEAD 10 Ii. Gn-oklC.rrigo. 1~7oZ 'i • MODERNIZE BANKING ... BUT WITH CARE IS PAilip A. Uxovortl • HOW DID GLASS-STEAGALL HAPPEN? 21 RtnlllnllI't:<kr /'17031 •A NONBANKER'S PERSPECIWE ON BANKING REFORM 1.9 • Willi". PM I'-/703 z • WHAT THE CANADIANS KNOW 33 CIr"rl" f'. Rllinl 1'17033 • UNTANGLING THE STAFFORD STUDENT LOAN PROGRAM 38 - JoupA J. f:gli. li70 '3 'I • FOOD SAFET\': A PATCHWORK SYSTEM 411 Willi•• III. l.oyd,. I'1 70 3<.. Jona'han Kw.ol. SA IIAGE INEQUAIJ71F,S: (.'HlllJRf:N IN 60 .WERlCA:~ SCHOOI's, rrvi,.,nIby RoI>m Gmt • Srep/lcn Hcs.... -- l./I'f: FROM CAPITOL Hill.!STUDIKI'OF CONGRf:SS ANIJ 1'Hf: IIIE/)/A. rrvin.vdby f'.lkrGrifJitir. Cover ilusuaioo by fohn Porter • THEG·A·O AQUARrERlYSflONSO«[O BY THL U.s. G[N(RAl. ACCOUNTING on ICE • JOURNAL • C_fll..",,/,r G"",ml • SIIIJ! • Et/i/fl,;"I....dtisory BINI'" of"" (IIIi'"'S',,"s JOli1\' F. -

24TH USDA Interagency Research Forum on Invasive Species January 8-11, 2013 Annapolis, Maryland

United States Forest FHTET-13-01 Department of Service March 2013 Agriculture Cover art: “Urban crawl” by Vincent D’Amico. Product Disclaimer Reference herein to any specific commercial products, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. EEO Statement The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. 24TH USDA Interagency Research Forum on Invasive Species January 8-11, 2013 Annapolis, Maryland Compiled by: 1 2 Katherine A. McManus and Kurt W. Gottschalk 1USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Hamden, CT 2USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Morgantown, WV For additional copies of this or the previous proceedings, contact Katherine McManus at (203) 230-4330 (email: [email protected]). -

Third Symposium on Hemlock Woolly Adelgid in the Eastern United States Asheville, North Carolina February 1-3, 2005

Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Hemlock Woolly Adelgid THIRD SYMPOSIUM ON HEMLOCK WOOLLY ADELGID IN THE EASTERN UNITED STATES ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA FEBRUARY 1-3, 2005 Brad Onken and Richard Reardon, Compilers Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team—Morgantown, West Virginia FHTET-2005-01 U.S. Department Forest Service June 2005 of Agriculture Most of the abstracts were submitted in an electronic format, and were edited to achieve a uniform format and typeface. Each contributor is responsible for the accuracy and content of his or her own paper. Statements of the contributors from outside of the U.S. Department of Agriculture may not necessarily reflect the policy of the Department. Some participants did not submit abstracts, and so their presentations are not represented here. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. References to pesticides appear in some technical papers represented by these abstracts. Publication of these statements does not constitute endorsement or recommendation of them by the conference sponsors, nor does it imply that uses discussed have been registered. Use of most pesticides is regulated by state and federal laws. Applicable regulations must be obtained from the appropriate regulatory agency prior to their use. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish and other wildlife if they are not handled and applied properly. -

Sugar Valley Saga

aALrLCP t-f/rl f l.-.$ t,H v tFt C 4 Jt, ,i,Ez--;F--/IEHl ? lfiHl By America'sMaster of LiteraryHumor GAM arr m'&'uM AUTHOROF THEKUDZU CHRON'CIES Sugar Valley Saga Carroll Gambrell SEVGO PRbSS PUBLISHERS NORTHPORT,ALABAMA QuotationstuomTHEWRECK OF THE HESPERUS,by H. W. Longfelloware used by thepermission of the HoughtonLibrary. Gambrell,Carroll, 1931- Sugar Valley SagaI Carroll Gambrell Copyright @ 1993by Carroll Gambrell All rights reserved.This book, or parts thereof,must not be usedor reproducedin anymanner without written permission of the publisher. NRST PRINTING- APRIL 1993 ISBN0-943487-42-0 PRINTEDINTHE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA SEVGOPRESS, 1955 22NqSTREET, NORTHPORT, ALABAMA 35476 Dedication.. To my threreaunts, the Ritter Sisters, who never allowed me to be homesick: Bertie Mae, who loved me and gave me her sparechange. Frankie, the big sister I never had, who read to me. 'til Teener,who scrubbedme the hide was gone,and told me talesI never forgot. Etemal love and eratitude . Thanksto: The Houghton Library, Inc. for permission to quote from H. W. l-ongfellow's immorral THE WRECK Otr THE HES?ERUS. SpecialThanks: To charlie Rudder,P'ofessor of Philosophyat the local collegc,rvho sct out to help-arrd did; who mea'l lo be a fric'd-and is; iuid rvhosc words and deedsare one. And. To Rich Oliver for his timely conlnlentsiurd skillful editing. Contents Prologue ......9 I Bears,BoarsAndBlueTicks . .....10 z FloydAndElwood . .i6 3 UglyRed . ....21 A a Chico's,SaturdayNight. ... .29 ( JakeAndloney ... .39 6 GoodbyeValley, Hello VulcanCity . .47 7 TheSugarBlues .... .58 B Mr. BatesGoes To Town . .69 9 Mrs.Vandcrwort'sRoomingHouse .