The Hooligan's OSR Kind-Of Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical Look at Technology and Society in Japan (1500-1900)

A Historical Look at Technology and Society in Japan (1500-1900) An essay based on a talk given by Dr. Eiichi Maruyama at the PART 1 Japan-Sweden Science Club (JSSC) annual meeting, Tokyo, 31 Gunpowder and Biotechnology October 1997. - Ukiyo-e and Microlithography Dr. Maruyama studied science history, scientific philosophy, and phys- In many parts of the world, and Japan was no exception, the 16th ics at the University of Tokyo. After graduating in 1959, he joined Century was a time of conflict and violence. In Japan, a number of Hitachi Ltd., and became director of the company’s advanced re- feudal lords were embroiled in fierce battles for survival. The battles search laboratory in 1985. He was director of the Angstrom Tech- produced three victors who attempted, one after another, to unify nology Partnership, and is currently a professor at the National Japan. The last of these was Ieyasu Tokugawa, who founded a “per- Graduate Institute for Policy Studies. manent” government which lasted for two and a half centuries before it was overthrown and replaced by the Meiji Government in Introduction 1868. Japanese industry today produces many technically advanced prod- ucts of high quality. There may be a tendency to think that Japan One particularly well documented battle was the Battle of Nagashino has only recently set foot on the technological stage, but there are in 1575. This was a showdown between the organized gunmen of numerous records of highly innovative ideas as far back as the 16th the Oda-Tokugawa Allies (two of the three unifiers) and the in- century that have helped to lay the foundations for the technologi- trepid cavalry of Takeda, who was the most formidable barrier to cal prowess of modern day Japan. -

The Wakasa.Pdf

The Wakasa tale: an episode occurred when guns were introduced in Japan F. A. B. Coutinho Faculdade de Medicina da USP Av. Dr. Arnaldo 455 São Paulo - SP 01246-903 Brazil e-mail: coutinho @dim.fm.usp.br Introduction : Very often the collector of Japanese swords becomes interested in both Japanese armor and Japanese matchlocks ( teppo or tanegashima ). Not surprisingly, however, the books that deal with swords generally deal very superficially with teppo: the little information provided on the history of teppo may not answer all the questions which may arise. In fact, most books mention only that the teppo were introduced in Japan by the Portuguese in 1543. Sometimes it is mentioned that this happened in Tanegashima , a small island in the south of Japan. Occasionally, some authors add a little more to the story; for example, I. Bottomley and A.P. Hobson ( Bottomley (1996) page 124) write that “the Lord of Tanegashima bought two teppo… for an exorbitant sum”. He asked his swordsmith to copy the guns. There were some technical problems which the swordsmith finally resolved “by exchanging his daughter for lessons with another Portuguese who arrived a short time after.” Also according to Hawley ( Hawley (1977 ) page 94), the governor of the Island tried to buy a gun: “…making all sorts of offers which the trader continued to refuse. Finally the governor, perhaps to soften him up, put on a big going-away feast complete with music, drinks and geisha . At this feast the trader got a glimpse of the governor´s daughter who was an outstanding beauty. -

The Introduction of Guns in Japanese History – from Tanegashima to the Boshin War – Oct.3 (Tue) to Nov

Special Exhibition The Introduction of Guns in Japanese History – From Tanegashima to the Boshin War – Oct.3 (Tue) to Nov. 26 (Sun), 2006 National Museum of Japanese History Outline of Exhibition The history of guns in Early Modern Japan begins with their arrival in 1543 and ends with the Boshin War in 1868. This exhibition looks at the influence that guns had on Japanese politics, society, military and technology over this period of three centuries, as well the unique development of this foreign culture and the process of change that took place while Japan was obtaining military techniques from Europe and the United States at the time of transition from the shogunate to a modern nation state. An enormous number of materials, approximately 300, including new discoveries, form this exhibition arranged in three parts. Since the National Museum of Japanese History first opened its doors, the Museum has conducted research on the history of guns and acquired more materials, mainly due to the efforts of Professor UDAGAWA Takehisa, the Museum's curator responsible for this exhibition. As a result of acquiring the three most renowned gun collections in Japan -- the YOSHIOKA Shin'ichi Gun Collection, ANZAI Minoru Gunnery Materials and part of the TOKORO Sokichi Gun Collection -- our collection of guns, related items and documents is the finest in Japan in terms of both quality and quantity. This exhibition is the culmination of many years spent acquiring guns and the findings of research conducted over that time. * “S.N.“ (Serial Numbers) in this explanatory pamphlet show the numbers written at the upper-left of white plates for each article on display. -

Telechargement

LA VERSION COMPLETE DE VOTRE GUIDE JAPON 2018/2019 en numérique ou en papier en 3 clics à partir de 9.99€ Disponible sur EDITION Directeurs de collection et auteurs : Bienvenue au Dominique AUZIAS et Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE Auteurs : Maxime DRAY, Barthélémy COURMONT, Antoine RICHARD, Matthieu POUGET-ABADIE, Arthur FOUCHERE, Maxence GORREGUES, Japon ! Jean-Marc WEISS, Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE, Dominique AUZIAS et alter Directeur Editorial : Stéphan SZEREMETA Responsable Editorial Monde : Patrick MARINGE Le Japon et ses habitants restent toujours un mystère fascinant Rédaction Monde : Caroline MICHELOT, Morgane pour la plupart d’entre nous. Les préjugés et les clichés, nous VESLIN, Pierre-Yves SOUCHET, Talatah FAVREAU le savons bien, ont la dent dure. Les Français ont la réputation Rédaction France : Elisabeth COL, Maurane d’être râleurs, prétentieux, et les Japonais insondables, trop CHEVALIER, Silvia FOLIGNO, Tony DE SOUSA polis même pour être sincères. Nous avons essayé dans cette FABRICATION nouvelle édition du guide Japon, plus complète, de vous donner Responsable Studio : Sophie LECHERTIER un éclairage global de la culture, des habitudes quotidiennes des assistée de Romain AUDREN Japonais, d’approcher ce magnifique pays sous divers aspects. Maquette et Montage : Julie BORDES, Le Japon possède une longue histoire, qui remonte aux Aïnous, Sandrine MECKING, Delphine PAGANO, une ethnie vivant sur l’île d’Hokkaido dans le nord du Japon dont Laurie PILLOIS et Noémie FERRON on a trouvé des traces vieilles de 12 000 ans ; et une modernité Iconographie : Anne DIOT incroyable en même temps, que l’on observe à chaque instant dans Cartographie : Jordan EL OUARDI les grandes métropoles nipponnes. L’archipel volcanique long de WEB ET NUMERIQUE plus de 3 000 kilomètres affiche une variété de paysages et de Directeur Web : Louis GENEAU de LAMARLIERE climats presque sans égale. -

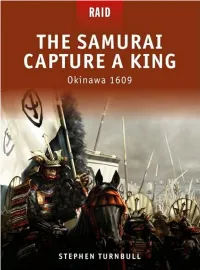

Raid 06, the Samurai Capture a King

THE SAMURAI CAPTURE A KING Okinawa 1609 STEPHEN TURNBULL First published in 2009 by Osprey Publishing THE WOODLAND TRUST Midland House, West Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 0PH, UK 443 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016, USA Osprey Publishing are supporting the Woodland Trust, the UK's leading E-mail: [email protected] woodland conservation charity, by funding the dedication of trees. © 2009 Osprey Publishing Limited ARTIST’S NOTE All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private Readers may care to note that the original paintings from which the study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, colour plates of the figures, the ships and the battlescene in this book Designs and Patents Act, 1988, no part of this publication may be were prepared are available for private sale. All reproduction copyright reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by whatsoever is retained by the Publishers. All enquiries should be any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, addressed to: photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be addressed to the Publishers. Scorpio Gallery, PO Box 475, Hailsham, East Sussex, BN27 2SL, UK Print ISBN: 978 1 84603 442 8 The Publishers regret that they can enter into no correspondence upon PDF e-book ISBN: 978 1 84908 131 3 this matter. Page layout by: Bounford.com, Cambridge, UK Index by Peter Finn AUTHOR’S DEDICATION Typeset in Sabon Maps by Bounford.com To my two good friends and fellow scholars, Anthony Jenkins and Till Originated by PPS Grasmere Ltd, Leeds, UK Weber, without whose knowledge and support this book could not have Printed in China through Worldprint been written. -

The Last Samurai: the Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori

THE LAST SAMURAI The Life and Battles of Saigo- Takamori MARK RAVINA John Wiley & Sons, Inc. THE LAST SAMURAI THE LAST SAMURAI The Life and Battles of Saigo- Takamori MARK RAVINA John Wiley & Sons, Inc. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2004 by Mark Ravina.All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada Design and production by Navta Associates, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as per- mitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, e-mail: [email protected]. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty:While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accu- racy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials.The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suit- able for your situation.You should consult with a professional where appropriate. -

Reinventing the Sword

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 Reinventing the sword: a cultural comparison of the development of the sword in response to the advent of firearms in Spain and Japan Charles Edward Ethridge Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Ethridge, Charles Edward, "Reinventing the sword: a cultural comparison of the development of the sword in response to the advent of firearms in Spain and Japan" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 3729. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3729 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REINVENTING THE SWORD: A CULTURAL COMPARISON OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE SWORD IN RESPONSE TO THE ADVENT OF FIREARMS IN SPAIN AND JAPAN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Charles E. Ethridge B.A., Louisiana State University, 1999 December 2007 Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Fredrikke Scollard, whose expertise, understanding, and patience added considerably to my graduate experience. I appreciate her knowledge of Eastern cultures and her drive to promote true ‘cross-cultural’ research. -

Il Samurai. Da Guerriero a Icona

Il fiume di parole e d’immagini sul Giappone che si riversò a icona Da guerriero Il samurai. in Occidente dopo il 1860 lo configurò per sempre come l’idillica terra del Monte Fuji, coi laghi sereni punteggiati di vele, le geisha in pose seminude e gli indomabili samurai dalle misteriose armature. Il fascino che i guerrieri giapponesi e la loro filosofia di vita esercitarono sulla cultura del Novecento fu pari soltanto al desiderio di conoscere meglio la loro storia e i loro costumi, per svelare i segreti di una casta che prima Il samurai. di sconfiggere il nemico in battaglia aveva deciso, senza rinunciare ai piaceri della vita, di educare il corpo e la mente Da guerriero a icona a sconfiggere i propri limiti e le proprie paure, per raggiungere l’impalpabile essenza delle cose. a cura di Moira Luraschi 10 10 Antropunti Collana diretta da Francesco Paolo Campione Christian Kaufmann Antropunti € 32,00 Collana diretta da Francesco Paolo Campione Il samurai. Christian Kaufmann Da guerriero a icona La Collezione Morigi e altre recenti acquisizioni del MUSEC a cura di Antropunti Moira Luraschi 10 Sommario Note di trascrizione Prefazione 6 e altre avvertenze per la lettura Roberto Badaracco La trascrizione delle parole giapponesi Per la lettura delle parole trascritte ci si ba- segue il Sistema Hepburn modificato, fa- serà sulla fonologia italiana per le vocali, su Saggi I samurai. Guerrieri, politici, intellettuali 11 cendo eccezione per quei pochi casi in cui quella inglese per le consonanti. Si tenga Moira Luraschi un nome è entrato nell’uso corrente in una dunque presente che: ch è la c semiocclu- forma diversa (es. -

1 This Is a Quick Tweaking of Minisix to Emulate the Old Fantasy Games Unlimited RPG, Bushido. Like Many an Old-School RPG, Bush

1 This is a quick tweaking of MiniSix to emulate the old Fantasy Games Unlimited RPG, Bushido. Like many an old-school RPG, Bushido is class-based, and to a certain extent these classes have been preserved by way of Perks & Complications. With that being said, the strength of MiniSix (and other non- class-based games, old and new) is that it doesn’t pigeonhole you. So if you want to play a courtly Samurai who doesn’t fight well, or a Yakuza who dabbles in magic (this may be a bit dangerous, but that's because of the place that d6 Bushido happens in, not because of class-based mechanics), or any other “non-standard” character type, go for it. This is the perfect system to try. Note that this system is not necessarily useful only in historical Japan. It is intended to be used in a mythical Japan, and as such is quite useful for playing other settings like Rokugan from Legend of the Five Rings. Typically used Special/Optional Rules from Md6 > Attributes may be purchased up to 5D, but all pips/dice over 4D cost double. More to keep the feel of what it is to be human in an inherently inhuman world with monsters and other magical creatures, though it is easily discarded—or the attribute cap changed—if a group wants more outright heroic- feeling character-building options. > A modified version of Traditional Open d6 Might Damage (½ Might or Lifting—whichever is higher— after ignoring pips; even-numbered Might/Lifting scores result in half-die plus one pip; no lower than 1D Might Damage). -

The Story of a Sleeping Beauty a 100-Monme Hand Cannon for the Bugyo Magistrate to Lord Mizuno

The Story of a Sleeping Beauty A 100-Monme Hand Cannon for the Bugyo Magistrate to Lord Mizuno Outline It is rare that the complete story of a pre-1870 Japanese Tanegashima matchlock is known. This present Ozutsu ‘hand cannon’ however, is signed in detail, and can be traced with some degree of certainty back to its very creation in late Edo Osaka Japan, then through its later travel to the United States, and afterwards to a long sleep in a castle in Ireland. After awaking, this 26-kilogram monster gun finally came full circle to complete a 75-year circumnavigation of the globe. If the fairy tale continues like this, it will be fired for the first time in over 150 years, to commemorate the new main gate at Tottori Castle in March of 2021. Background It might be easier to start right at the beginning, but for us this story starts somewhere in the middle with the discovery of this gun in Castle Matrix in Ireland. Originally built in the 1400s, the castle has had a romantic history, falling into ruins until repurposed into a family home, and then a hotel in more recent years. Now once more it is becoming neglected, the woods gradually surrounding it, as in the story of the Sleeping Beauty. There was a collection of Japanese artefacts inside, rusting and molding away in a vast pile, and the whole lot was owned by the widow of a United States Colonel, John Joffre (aka ‘Sean’) O’Driscoll. According to an article in Eire’s Independent Newspaper, this Irish-American Colonel O’Driscoll was an aide to General Douglas MacArthur while accepting the surrender of the Japanese in 1945. -

Meiji Intellectuals and the Japanese Construction of an East-West Binary, 1868-1912

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-7-2011 Finding their Place in the World: Meiji Intellectuals and the Japanese Construction of an East-West Binary, 1868-1912 Masako N. Racel Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Racel, Masako N., "Finding their Place in the World: Meiji Intellectuals and the Japanese Construction of an East-West Binary, 1868-1912." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/26 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINDING THEIR PLACE IN THE WORLD: MEIJI INTELLECTUALS AND THE JAPANESE CONSTRUCTION OF AN EAST-WEST BINARY 1868-1912 BY MASAKO NOHARA RACEL Under the Direction of Douglas R. Reynolds ABSTRACT The Meiji era (1868-1912) in Japanese history was characterized by the extensive adoption of Western institutions, technology, and customs. The dramatic changes that took place caused the era’s intellectuals to ponder Japan's position within the larger global context. The East-West binary was a particularly important part of the discourse as the intellectuals analyzed and criticized the current state of affairs and offered their visions of Japan’s future. This dissertation examines five Meiji intellectuals who had very different orientations and agendas: Fukuzawa Yukichi, an influential philosopher and political theorist; Shimoda Utako, a pioneer of women's education; Uchimura Kanzō, a Christian leader; Okakura Kakuzō, an art critic; and Kōtoku Shūsui, a socialist. -

A BOWL for a COIN a Commodity History Of

A BOWL FOR A COIN A BOWL FOR A COIN A Commodity History of Japanese Tea William Wayne Farris University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu © 2019 University of Hawai‘i Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Farris, William Wayne, author. Title: A bowl for a coin: a commodity history of Japanese tea / William Wayne Farris. Description: Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018040370 | ISBN 9780824876609 (cloth alk. paper) Amazon Kindle 9780824878528 EPUB 9780824882624 PDF 9780824882617 Subjects: LCSH: Tea—Japan—History. | Tea trade—Japan—History. Classification: LCC HD9198.J32 F37 2019 | DDC 338.1/73720952–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017025008 Cover art: Tea peddlers around 1400. Source: "A Bowl for a Coin (ippuku issen)," Shichijūichi ban shokunin utaawase emaki (artist unknown). TNM Image Archives. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. The open-access ISBNs for this book are 9780824882617 (PDF) and 9780824882624 (EPUB). More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The open access version of this book is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means that the work may be freely downloaded and shared for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require permission from the publisher.