Kinship, Inheritance, and the Environment in Medieval Japan By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Download

VOLUME 1: BORDERS 2018 Published by National Institute of Japanese Literature Tokyo EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor IMANISHI Yūichirō Professor Emeritus of the National Institute of Japanese 今西祐一郎 Literature; Representative Researcher Editors KOBAYASHI Kenji Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 小林 健二 SAITō Maori Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 齋藤真麻理 UNNO Keisuke Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 海野 圭介 Literature KOIDA Tomoko Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 恋田 知子 Literature Didier DAVIN Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese ディディエ・ダヴァン Literature Kristopher REEVES Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese クリストファー・リーブズ Literature ADVISORY BOARD Jean-Noël ROBERT Professor at Collège de France ジャン=ノエル・ロベール X. Jie YANG Professor at University of Calgary 楊 暁捷 SHIMAZAKI Satoko Associate Professor at University of Southern California 嶋崎 聡子 Michael WATSON Professor at Meiji Gakuin University マイケル・ワトソン ARAKI Hiroshi Professor at International Research Center for Japanese 荒木 浩 Studies Center for Collaborative Research on Pre-modern Texts, National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) National Institutes for the Humanities 10-3 Midori-chō, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-0014, Japan Telephone: 81-50-5533-2900 Fax: 81-42-526-8883 e-mail: [email protected] Website: https//www.nijl.ac.jp Copyright 2018 by National Institute of Japanese Literature, all rights reserved. PRINTED IN JAPAN KOMIYAMA PRINTING CO., TOKYO CONTENTS -

No.723 (April Issue)

NBTHK SWORD JOURNAL ISSUE NUMBER 723 April, 2017 Meito Kansho Examination of Important Swords Juyo Bijutsu Hin Important Art Object Type: Tachi Owner: Mori Kinen (memorial) Shu-sui Museum Mei: Toshitsune Length: 2 shaku 3 sun1 bu 8 rin (70.25 cm) Sori: 9 bu 6 rin (2.9 cm) Motohaba: 9 bu 2 rin (2.8 cm) Sakihaba: 6 bu 3 rin (1.9 cm) Motokasane: 2 bu (0.6 cm) Sakikasane: 1 bu 1 rin (0.35 cm) Kissaki length: 8 bu 6 rin (2.6 cm) Nakago length: 6 sun 5 bu 7 rin (19.9 cm) Nakago sori: 1 bu (0.3 rin) Commentary This is a shinogi zukuri tachi with an ihorimune, a standard width, and there is not much difference in the widths at the moto and saki. It is slightly thick, there is a large koshi-sori with funbari, the tip has a prominent sori, and there is a short chu- kissaki. The jihada is itame mixed with mokume, the entire jihada is well forged, and some areas have a fine ko-itame jihada. There are ji-nie, chikei along the itame hada areas, and jifu utsuri. The entire hamon is high, and composed of ko- gunome mixed with ko-choji, square gunome, and togariba. The hamon’s vertical alterations are not prominent, and in some places it is a suguha type hamon. There are ashi and yo, a nioiguchi, a little bit of uneven fine mura, and mizukaze-like utsuri at the koshimoto is very clear and almost looks like a hamon. -

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi No Kumi (Confraria De Misericórdia)

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi no Kumi (Confraria de Misericórdia) Takashi GONOI Professor Emeritus, University of Tokyo Introduction During the 80-year period starting when the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier and his party arrived in Kagoshima in August of 1549 and propagated their Christian teachings until the early 1630s, it is estimated that a total of 760,000 Japanese converted to Chris- tianity. Followers of Christianity were called “kirishitan” in Japanese from the Portu- guese christão. As of January 1614, when the Tokugawa shogunate enacted its prohibi- tion of the religion, kirishitan are estimated to have been 370,000. This corresponds to 2.2% of the estimated population of 17 million of the time (the number of Christians in Japan today is estimated at around 1.1 million with Roman Catholics and Protestants combined, amounting to 0.9% of total population of 127 million). In November 1614, 99 missionaries were expelled from Japan. This was about two-thirds of the total number in the country. The 45 missionaries who stayed behind in hiding engaged in religious in- struction of the remaining kirishitan. The small number of missionaries was assisted by brotherhoods and sodalities, which acted in the missionaries’ place to provide care and guidance to the various kirishitan communities in different parts of Japan. During the two and a half centuries of harsh prohibition of Christianity, the confraria (“brother- hood”, translated as “kumi” in Japanese) played a major role in maintaining the faith of the hidden kirishitan. An overview of the state of the kirishitan faith in premodern Japan will be given in terms of the process of formation of that faith, its actual condition, and the activities of the confraria. -

Japonica Humboldtiana 8 (2004)

JAPONICA HUMBOLDTIANA 8 (2004) Contents MARKUS RÜTTERMANN Ein japanischer Briefsteller aus dem ‘Tempel zu den hohen Bergen’ Übersetzung und Kommentar einer Heian-zeitlichen Handschrift (sogenanntes Kôzanjibon koôrai). Zweiter und letzter Teil ............ 5 GERHILD ENDRESS Ranglisten für die Regierungsbeamten des Hofadels Ein textkritischer Bericht über das Kugyô bunin ............................. 83 STEPHAN KÖHN Alles eine Frage des Geschmacks Vom unterschiedlichen Stellenwert der Illustration in den vormodernen Literaturen Ost- und Westjapans .................... 113 HARALD SALOMON National Policy Films (kokusaku eiga) and Their Audiences New Developments in Research on Wartime Japanese Cinema.............................................................................. 161 KAYO ADACHI-RABE Der Kameramann Miyagawa Kazuo................................................ 177 Book Reviews SEPP LINHART Edo bunko. Die Edo Bibliothek. Ausführlich annotierte Bibliographie der Blockdruckbücher im Besitz der Japanologie der J. W. Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main als kleine Bücherkunde und Einführung in die Verlagskultur der Edo-Zeit Herausgegeben von Ekkehard MAY u.a............................................ 215 4 Contents REGINE MATHIAS Zur Diskussion um die “richtige” Geschichte Japans Steffi RICHTER und Wolfgang HÖPKEN (Hg.): Vergangenheit im Gesellschaftskonflikt. Ein Historikerstreit in Japan; Christopher BARNARD: Language, Ideology, and Japanese History Textbooks ........................................................................... -

The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection

NEWS RELEASE November, 2009 The Lineage of Culture – The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection The Tokyo National Museum is pleased to present the special exhibition “The Lineage of Culture—The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection” from Tuesday, April 20, to Sunday, June 6, 2010. The Eisei Bunko Foundation was established in 1950 by 16th-generation family head Hosokawa Moritatsu with the objective of preserving for future generations the legacy of the cultural treasures of the Hosokawa family, lords of the former Kumamoto domain. It takes its name from the “Ei” of Eigen’an—the subtemple of Kenninji in Kyoto, which served as the family temple for eight generations from the time of the original patriarch Hosokawa Yoriari, of the governing family of Izumi province in the medieval period— and the “Sei” of Seiryūji Castle, which was home to Hosokawa Fujitaka (better known as Yūsai), the founder of the modern Hosokawa line. Totaling over 80,000 objects, it is one of the leading collections of cultural properties in Japan and includes archival documents, Yūsai’s treatises on waka poetry, tea utensils connected to the great tea master Sen no Rikyū from the personal collection of 2nd-generation head Tadaoki (Sansai), various objects associated with Hosokawa Gracia, and paintings by Miyamoto Musashi. The current exhibition will present the history of the Hosokawa family and highlight its role in the transmission of traditional Japanese culture—in particular the secrets to understanding the Kokinshū poetry collection, and the cultural arts of Noh theater and the Way of Tea—by means of numerous treasured art objects and historical documents that have been safeguarded through the family’s tumultuous history. -

Kumazawa Agonistes: the Right of Conquest and the Rise of Democratic Ideology (Part One)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE 【論文】 Kumazawa Agonistes: The Right of Conquest and the Rise of Democratic Ideology (Part One) Jason M. Morgan Introduction:TheKumazawaCase TO: General MacARTHUR. A very curious letter came across Douglas MacArthurʼs FROM: KUMAZAWA, Hiromichi (熊沢寛道) desk on August 11, 1947. It was hardly the only letter to arrive KYOTO To, SAKYO ku, TANAKA KITAHARUNA – 1. that day, to be sure. MacArthur was the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers—SCAP—and essentially the de facto DATE: (No date.) shogun of Japan. Since Japanʼs defeat in the Greater East Asia War, MacArthur had reigned as head of General Headquarters, The writer states that during the period when the Imperial GHQ, and, in effect, as the benevolent dictator of the entire throne was divided between the Northern and Southern archipelago. Dynasties, Emperor GOKOMATSU (後小松) of the The SCAP archives, housed in the National Diet Library Northern Dynasty killed Prince JITSUHITO (実仁), son in Nagatachō, contain boxes and boxes of microfiched letters and heir of Emperor GOKAMEYAMA (後亀山) of the to the power behind the Chrysanthemum Throne. Summarized Southern Dynasty, thus putting an end to the Southern and also mimeographed from the originals, the letters touch Dynasty. The Northern Dynasty then became sole on every conceivable subject, from complaints about the black claimant to the Imperial throne. market and concerns about building practices to denunciations of individuals and organizations for reasons both public- The writer has conducted extensive research throughout minded and personal, profound and petty. NARA, MIE, FUKUSHIMA, and AICHI prefectures But one letter stands out. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

Vegetable Production and the Diet in Rural Villages by Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University)

Vegetables and the Diet of the Edo Period, Part 2 Vegetable Production and the Diet in Rural Villages By Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University) Introduction compiled by Tomita Iyahiko and completed in 1873, describes the geography and culture of Hida During the Edo period (1603–1868), the number of province. It contains records from 415 villages in villages in Japan remained fairly constant with three Hida counties, including information on land roughly 63,200 villages in 1697 and 63,500 140 years value, number of households, population and prod- later in 1834. According to one source, the land ucts, which give us an idea of the lifestyle of these value of an average 18th and 19th century village, with villagers at the end of the Edo period. The first print- a population of around 400, was as much as 400 to ed edition of Hidago Fudoki was published in 1930 500 koku1, though the scale and character of each vil- (by Yuzankaku, Inc.), and was based primarily on the lage varied with some showing marked individuality. twenty-volume manuscript held by the National In one book, the author raised objections to the gen- Archives of Japan. This edition exhibits some minor eral belief that farmers accounted for nearly eighty discrepancies from the manuscript, but is generally percent of the Japanese population before and during identical. This article refers primarily to the printed the Edo period. Taking this into consideration, a gen- edition, with the manuscript used as supplementary eral or brief discussion of the diet in rural mountain reference. -

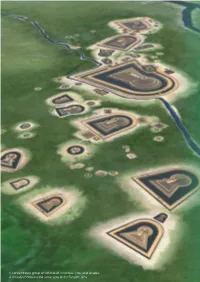

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

Elsewhere, to Support His Contention That the Themes of Modern Erotic

book reviews 267 Elsewhere, to support his contention that the themes of modern erotic poetry are not new to Tibetan literature, the author supplies copious examples from pre-modern writings. These range from the cryptic sensuality of some ka¯ vya-inspired lines, to the outright crudity and bawdiness of more popular literature. This is a revealing and entertaining journey through a regularly overlooked area of Tibetan writing. The relevance of some examples here, and even whether they all belong in a single category, seems more debat- able. The universality of the themes of sex and bodily functions makes it difficult to depict their reappear- ance as a literary continuity. Correspondences and recurrences, especially spread over so many centuries, do not necessarily represent continuation. Doubts about categories and continuity might also be raised in rela- tion to the author’s discussion on “the Tibetan Tradition of Social Criticism” (Chapter 3). I welcome the author’s decision to place politics centre-stage. Rather than a mere backdrop, the pol- itical situation is the crucible in which modern Tibetan literature has been forged. The battle between censorship and creativity continues to shape this most vibrant and dynamic form of Tibetan literature. However, in emphasizing the continuity of indigenous writing, the book underplays debts to foreign literature. In the essay and short-story genres (also innovations by the modern movement) these are especially obvious, but this volume hardly mentions them. A majority of the influential first-generation writers attended the same educational institutions. Their compositions reflect their exposure to an array of traditions: Chinese, Western, and Communist, as well as Tibetan.