The Age of Gunpowder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Guardia-Pyke Bomb Carriers James A

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 34 | Issue 3 Article 8 1943 La Guardia-Pyke Bomb Carriers James A. Pyke Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation James A. Pyke, La Guardia-Pyke Bomb Carriers, 34 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 198 (1943-1944) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE LA GUARDIA-PYKE BOMB CARRIERS* James A. Pyket Soon after the World's Fair bomb explosion of July 4, 1940, in which two members of the New York Police Department were killed and several injured, the Honorable Fiorello H. La Guardia, Mayor of the City of New York, summoned the author, as Com- manding Officer of the Bomb Squad, to the City Hall for the pur- pose of discussing the catastrophe and means of preventing a re- currence. As the result of this and several other conferences the "La Guardia-Pyke Bomb Carriers" were developed. The purpose of these carriers is to take a bomb from a congested area to a remote or suburban district and to do so in a manner which will protect the public and the police. With the construc- tion adopted should the bomb explode enroute the explosive forces are reduced to a minimum by means of a triple air-cushioning effect produced by the baffle screens of woven steel cable. -

Conventional Explosions and Blast Injuries 7

Chapter 7: CONVENTIONAL EXPLOSIONS AND BLAST INJURIES David J. Dries, MSE, MD, FCCM David Bracco, MD, EDIC, FCCM Tarek Razek, MD Norma Smalls-Mantey, MD, FACS, FCCM Dennis Amundson, DO, MS, FCCM Objectives ■ Describe the mechanisms of injury associated with conventional explosions. ■ Outline triage strategies and markers of severe injury in patients wounded in conventional explosions. ■ Explain the general principles of critical care and procedural support in mass casualty incidents caused by conventional explosions. ■ Discuss organ-specific support for victims of conventional explosions. Case Study Construction workers are using an acetylene/oxygen mixture to do some welding work in a crowded nearby shopping mall. Suddenly, an explosion occurs, shattering windows in the mall and on the road. The acetylene tank seems to be at the origin of the explosion. The first casualties arrive at the emergency department in private cars and cabs. They state that at the scene, blood and injured people are everywhere. - What types of patients do you expect? - How many patients do you expect? - When will the most severely injured patients arrive? - What is your triage strategy, and how will you triage these patients? - How do you initiate care in victims of conventional explosions? Fundamental Disaster Management I . I N T R O D U C T I O N Detonation of small-volume, high-intensity explosives is a growing threat to civilian as well as military populations. Understanding circumstances surrounding conventional explosions helps with rapid triage and recognition of factors that contribute to poor outcomes. Rapid evacuation of salvageable victims and swift identification of life-threatening injuries allows for optimal resource utilization and patient management. -

Shipwreck Cannons Gwen Wright

Season 6, Episode 9: Shipwreck Cannons Gwen Wright: Our first story investigates a maritime mystery washed up on an Oregon beach. 1846: tensions between the U.S. and Britain are approaching a boiling point. All eyes are focused on the disputed border between the U.S. and the British colonial territory of Canada. At stake is ownership of the enormous riches of some 300,000 square miles of the Pacific Northwest. The U.S. needs reconnaissance, and dispatches an armed naval vessel – the USS Shark . But that September disaster strikes; the Shark wrecks and sinks at the treacherous mouth of the Columbia River. More than a century and a half later, fourteen-year-old Miranda Petrone, from Tualatin, Oregon, thinks she may have found a piece of this historic ship. Miranda: Me and my dad were walking along the beach. And I saw this big thing with rust. And I’m like, hey dad, come here. Gwen: I’m Gwen Wright, nice to meet you. So I heard you found something pretty interesting around here. Miranda: Yeah. Gwen: What was it? Miranda: We found a cannon. Gwen: Now, are you sure it was a cannon? Miranda: Well, not at first. Me and my dad were walking along the beach. Then there was this big black rocky thing so I went up a little closer and eventually saw rust. I thought, rocks aren't supposed to have rust. And so, I called my dad over. He came and checked it out. He's like, huh, maybe it's a cannon. He was just joking though. -

The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb Peter A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-60954-8 - The Asian Military Revolution: From Gunpowder to the Bomb Peter A. Lorge Frontmatter More information The Asian Military Revolution Records show that the Chinese invented gunpowder in the 800s. By the 1200s they had unleashed the first weapons of war upon their unsus- pecting neighbors. How did they react? What were the effects of these first wars? This extraordinarily ambitious book traces the history of that invention and its impact on the surrounding Asian world – Korea, Japan, Southeast Asia and South Asia – from the ninth through the twentieth century. As the book makes clear, the spread of war and its technology had devastating consequences on the political and cultural fabric of those early societies although each reacted very differently. The book, which is packed with information about military strategy, interregional warfare, and the development of armaments, also engages with the major debates and challenges traditional thinking on Europe’s contri- bution to military technology in Asia. Articulate and comprehensive, this book will be a welcome addition to the undergraduate classroom and to all those interested in Asian studies and military history. PETER LORGE is Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at Vanderbilt University, Tennessee. His previous publications include War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China (2005) and The International Reader in Military History: China Pre-1600 (2005). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-60954-8 - The Asian Military Revolution: From Gunpowder to the Bomb Peter A. Lorge Frontmatter More information New Approaches to Asian History This dynamic new series will publish books on the milestones in Asian history, those that have come to define particular periods or mark turning-points in the political, cultural and social evolution of the region. -

The International History Bee and Bowl Asian Division Study Guide!

The International History Bee and Bowl Asian Division Study Guide Welcome to the International History Bee and Bowl Asian Division Study Guide! To make the Study Guide, we divided all of history into 5 chapters: Middle Eastern and South Asian History, East and Southeast Asian History, US American History, World History (everything but American and Asian) to 1789, and World History from 1789-present. There may also be specific questions about the history of each of the countries where we will hold tournaments. A list of terms to be familiar with for each country is included at the end of the guide, but in that section, just focus on the country where you will be competing at your regional tournament (at least until the Asian Championships). Terms that are in bold should be of particular focus for our middle school division, though high school competitors should be familiar with these too. This guide is not meant to be a complete compendium of what information may come up at a competition, but it should serve as a starting off point for your preparations. Certainly there are things that can be referenced at a tournament that are not in this guide, and not everything that is in this guide will come up. At the end of the content portion of the guide, some useful preparation tips are outlined as well. Finally, we may post additional study materials, sample questions, and guides to the website at www.ihbbasia.com over the course of the year. Should these become available, we will do our best to notify all interested schools. -

ASTRA MILITARUM SOLDIERS of the IMPERIUM These Datasheets Allow You to Fight Apocalypse Battles with Your Astra Militarum Miniatures

ASTRA MILITARUM SOLDIERS OF THE IMPERIUM These datasheets allow you to fight Apocalypse battles with your Astra Militarum miniatures. Each datasheet includes the characteristics profiles of the unit it describes, as well as any wargear and special abilities it may have. KEYWORDS Throughout these datasheets you will come across the <Regiment> keyword. This is shorthand for a keyword of your choosing, as described below. <REGIMENT> Most Astra Militarum units are drawn from a regiment. Some datasheets specify which regiment the unit is drawn from (e.g. Mukaali Riders have the Tallarn keyword, so are drawn from the Tallarn Regiment), but where a datasheet does not, it will have the <Regiment> keyword. When you include such a unit in your army, you must nominate which regiment that unit is from. You then simply replace the <Regiment> keyword in every instance on that unit’s datasheet with the name of your chosen regiment. For example, if you were to include an Atlas Recovery Tank in your army, and you decided it was from Vostroya, its <Regiment> Faction keyword is changed to Vostroyan and its Recovery Vehicle ability would then read: ‘At the end of the Action phase, this unit can to repair one friendly Vostroyan Vehicle unit in base contact with it. If it does, remove one damage marker from that Vehicle unit. Only one attempt to repair each unit can be made each turn.’ ATLAS RECOVERY TANK 5 An Atlas Recovery Tank is a unit that contains 1 model. It is equipped with: Heavy Bolter; Armoured Hull. M WS BS A W Ld Sv Atlas Recovery Tank 12" 6+ 4+ 1 2 5 6+ WEAPON TYPE RANGE A SAP SAT ABILITIES Heavy Bolter Heavy 36" 1 7+ 9+ - Heavy Stubber Heavy 36" 1 8+ 10+ - Storm Bolter Small Arms 24" 1 9+ 10+ Rapid Fire Armoured Hull Melee Melee User 10+ 10+ - WARGEAR OPTIONS • This unit can also be equipped with one of the following (Power Rating +1): 1 Heavy Stubber; 1 Storm Bolter. -

SPANISH FORK PAGES 1-20.Indd

November 14 - 20, 2008 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, November 14 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey b News (N) b CBS Evening News (N) b Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Threshold” The Price Is Right Salutes the NUMB3RS “Charlie Don’t Surf” News (N) b (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight (N) b Troops (N) b (N) b Letterman (N) KJZZ 3 High School Football The Insider Frasier Friends Friends Fortune Jeopardy! Dr. Phil b News (N) Sports News Scrubs Scrubs Entertain The Insider The Ellen DeGeneres Show Ac- News (N) World News- News (N) Access Holly- Supernanny “Howat Family” (N) Super-Manny (N) b 20/20 b News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4 tor Nathan Lane. (N) Gibson wood (N) b line (N) wood (N) (N) b News (N) b News (N) b News (N) b NBC Nightly News (N) b News (N) b Deal or No Deal A teacher returns Crusoe “Hour 6 -- Long Pig” (N) Lipstick Jungle (N) b News (N) b (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night KSL 5 News (N) to finish her game. b Jay Leno (N) b TBS 6 Raymond Friends Seinfeld Seinfeld ‘The Wizard of Oz’ (G, ’39) Judy Garland. (8:10) ‘Shrek’ (’01) Voices of Mike Myers. -

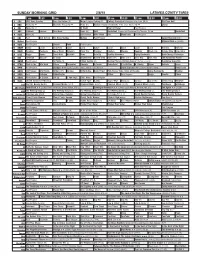

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

He Ideals of the Eas Ith Special Refereno O The

HE I DEALS OF THE EAS I TH SPECI AL REFERENO O THE A R T O F J A PA N " 11 7 3 2. BY KAKUZO O KAKURA L O N D O N J O HN URRAY ALBE ARLE S TREET M , M 1905 PRE FATO RY NO TE wishes to point ou t tha t this book is wr i tten in by a na i a n t ve qf J ap . CO N TE N TS I NTRODUCTI O N THE RANGE O F I DEALS THE PRI MITI VE A RT O F J APAN CON FUCIANI S M NO RTHERN CH I NA LAO I S M AND TAO I S M — S O UTH ERN CH I NA BUDD H I S M AND INDIAN ART — THE AS UKA PERI OD ( 5 5 0 700 A .D .) — 1 08 THE NARA PE RI OD (700 8 00 A .O .) - 1 28 THE HEIAN PERIOD (8 00 900 AD .) W — THE FUJ I ARA PE RIOD (900 1200 A.D .) K K 1 2 - 40 A D THE AMA URA PERIOD ( 00 1 0 . .) 1 4 0- 1 w AS HI KAGA PERI OD ( 0 600 .) Vll C ONTENTS PAGE TOYOTO MI AN D EARLY TO KUGAWA — PERI OD ( 1 600 1 700 A n.) LATER TO KU GAWA PERIOD ( 1 700. 1 8 5 0 A .D .) THE M EIJI PERI OD ( 1 8 5 0 TO THE PRESE NT DAY ) THE V I STA I N T R O D U C T I O N K A KUZ O K A KURA t his O , the author of work on Japanese A r t Ideals— and the t future au hor, as we hope , of a longer and completely illustrated book on the same subject— has been long known to his own people and to others as the foremost living authority on Oriental Archaeology and Art . -

Acta Aquatica Aquatic Sciences Journal

p-ISSN. 2406-9825 Acta Aquatica: Aquatic Sciences Journal, 7:1 (April, 2020): 37-39 e-ISSN. 2614-3178 Acta Aquatica Aquatic Sciences Journal The occurrence of the Atlantic species Pisodonophis semicinctus (Osteichthyes: Ophichthidae) in the Gulf of Antalya, Turkey Mehmet Gökoğlu a, *, Erkan Biçer b, Kemal Gökoğlu c , Jale Korun a and Serkan Teker a a Faculty of Fisheries, Akdeniz University, Turkey b Antalya Directorate of Provincial Agricultural and Forestry c Akdeniz Üniversity Abstract Fishermen caught a different eel species at night with hook on July 7, 2019 (36°48'59.21"N: 30°38'23.44"E). This fish has not been seen before in the Gulf of Antalya. This fish was identified as Pisodonophis semicinctus (Richardson, 1848). With the identification of this fish, a new species was added to the fish fauna of the Gulf of Antalya. In the present paper, we reported P. semicinctus for the first time from the Gulf of Antalya, Turkey (North-Eastern Mediterranean), for the third time from marine waters of Turkey. Keywords: Occurence; Pisodonophis semicinctus; the Gulf of Antalya 1. Introduction Eight species of eel belonging to the Ophichthidae family are reported in the Mediterranean Sea. One of these fish The Mediterranean Sea was connected to both the is P. semicinctus (Bodilis et al. 2012). The species which its main Atlantic and the Indian Ocean with the opening of the Suez habitat is the East Atlantic coast is very rare in the Canal in 1869. Therefore, there are migrations from both Mediterranean Sea (Ragonese and Giusto, 2000; Ambrogi oceans to the Mediterranean Sea. -

Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy 1

Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy 1 Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Artillery Through the Ages A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America Author: Albert Manucy Release Date: January 30, 2007 [EBook #20483] Language: English Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ARTILLERY THROUGH THE AGES *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Christine P. Travers and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net ARTILLERY THROUGH THE AGES A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. -- Price 35 cents (Cover) FRENCH 12-POUNDER FIELD GUN (1700-1750) ARTILLERY THROUGH THE AGES A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy 3 by ALBERT MANUCY Historian Southeastern National Monuments Drawings by Author Technical Review by Harold L. Peterson National Park Service Interpretive Series History No. 3 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1949 (Reprint 1956) Many of the types of cannon described in this booklet may be seen in areas of the National Park System throughout the country. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei