Charitable Giving in Mass Media: Opinions & Insights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Student Success

TRANSFORMING School Environments OUR VISION For Student Success Weaving SKILLS ROPES Relationships 2018 Annual Report Practices to Help All Students Our Vision for Student Success City Year has always been about nurturing and developing young people, from the talented students we serve to our dedicated AmeriCorps members. We put this commitment to work through service in schools across the country. Every day, our AmeriCorps members help students to develop the skills and mindsets needed to thrive in school and in life, while they themselves acquire valuable professional experience that prepares them to be leaders in their careers and communities. We believe that all students can succeed. Supporting the success of our students goes far beyond just making sure they know how to add fractions or write a persuasive essay—students also need to know how to work in teams, how to problem solve and how to work toward a goal. City Year AmeriCorps members model these behaviors and mindsets for students while partnering with teachers and schools to create supportive learning environments where students feel a sense of belonging and agency as they develop the social, emotional and academic skills that will help them succeed in and out of school. When our children succeed, we all benefit. From Our Leadership Table of Contents At City Year, we are committed to partnering Our 2018 Annual Report tells the story of how 2 What We Do 25 Campaign Feature: with teachers, parents, schools and school City Year AmeriCorps members help students 4 How Students Learn Jeannie & Jonathan Lavine districts, and communities to ensure that all build a wide range of academic and social- 26 National Corporate Partners children have access to a quality education that emotional skills to help them succeed in school 6 Alumni Profile: Andrea Encarnacao Martin 28 enables them to reach their potential, develop and beyond. -

2019 National Voter Registration Day Final Report

National Voter Registration Day 2019 FINAL REPORT Contents Introduction ..………………………………………………………3 Background ……………………………………………………….. 4 By the Numbers ……………………………………………………5 Election Officials .……….………………………………………..12 Across the Aisle …………………………………………………..13 Premier Partners ……………………..…………………….........14 Premier Partners - Nonprofits ..…………………….................16 Premier Partners - Media & Tech Partners .…………………... 25 Premier Partners - Celebrities & Social Media Influencers .... 29 On the Airwaves and in Print ………………………………….. 31 Stories from the Field …………………………………………... 32 Supporting, Innovating, and Scaling Up ……………………... 35 National Voter Registration Day 2020 .………………………. 37 Financials …………………………………………………………38 Acknowledgements …………………………………………….. 39 Sponsor Opportunities ………………………………………… 40 NationalVoterRegistrationDay.org 192 Introduction A very special thanks to all of the partners across the country who hit the streets, the airwaves, and the Internet on September 24 to make 2019’s National Voter Registration Day a success beyond our wildest expectations. With this report, we celebrate the success of the holiday As members of National Voter Registration Day’s Steering Committee, and its growing role in strengthening our shared democracy. we are pleased to share results from the 2019 holiday. This year’s success demonstrates the holiday’s growing momentum and place as a With your help in 2019, we registered over 470,000 milestone in local and national electoral processes alike. voters, had one million face-to-face conversations about -

Tools That Build a Better Future

Tools that build a better future Annual Report FY2018 July 1, 2017 – June 30, 2018 Habitat for Humanity International The tools in our toolbox ______________________ 2 Annual Report FY2018 Celebrating our global numbers _________________ 17 Summary of individuals served _________________ 22 July 1, 2017 – June 30, 2018 Letter from the chair of the board habitat.org of directors and the CEO _________________________ 24 A commitment to global stewardship _________ 25 Financial statements ______________________________ 26 FY18 feature spotlights ___________________________ 28 Corporate, foundation, institution and individual support ____________________________ 33 Tithe ___________________________________________________ 45 Donations _____________________________________________ 46 Board of directors and senior leadership ____ 49 “It’s a unique set of tools that builds a future, and I think Habitat is that toolbox that just brings it all together.” Habitat Humanitarian Since our founding in 1976, Habitat for Humanity has helped more Jonathan Scott than 22 million people build or improve the place they call home. With your support, in fiscal year 2018 alone, we most, we also faithfully bring a few of our helped more than 8.7 million people, and an favorite tried-and-true tools to the workbench. additional 2.2 million gained the potential to improve Volunteerism, service, advocacy, awareness. their living conditions through training and advocacy. These engines — fueled by your generous We’ve accomplished all of this with the trowel and support — propel the inclusion, innovation and the power saw, to be sure, but also by working inspiration that are hallmarks of our work around alongside families to help them access the tools the world. they need for a better tomorrow. -

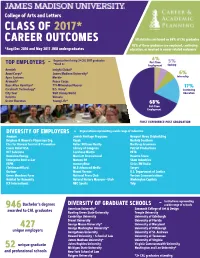

Class of 2017* Career Outcomes

College of Arts and Letters CLASS OF 2017* CAREER OUTCOMES All statistics are based on 84% of CAL graduates 95% of these graduates are employed, continuing *Aug/Dec 2016 and May 2017 JMU undergraduates education, or involved in career-related endeavors Organizations hiring 3+ CAL 2017 graduates 4% – Part Time 5% TOP EMPLOYERS *Hired 5+ Employment Seeking Aerotek Insight Global* AmeriCorps* James Madison University* 6% Apex Systems Merkle Internship Aramark* Peace Corps Booz Allen Hamilton* TTI-Milwaukee/Hoover 17% Carahsoft Technology* U.S. Army* Continuing City Year Walt Disney World Education Deloitte Winvale Grant Thornton Young Life* 68% Full-Time Employment FIRST EXPERIENCE POST GRADUATION DIVERSITY OF EMPLOYERS – Organizations representing a wide range of industries Amazon Jewish Heritage Programs Newport News Shipbuilding Brigham & Women’s Physicians Org. Kayak Norfolk Southern Ctrs for Disease Control & Prevention Keller Williams Realty Northrup Grumman Comic Relief USA Library of Congress Patriot Productions DLT Solutions Lockheed Martin PETA Dominion Energy Marriott International Rosetta Stone Enterprise Rent-a-Car Maroon PR Shaw Industries ESPN memoryBlue Sirius XM Radio FleishmanHillard MLB Advanced Media Target Gartner Mount Vernon U.S. Department of Justice Green Meadows Farm National Press Club Verizon Communications Habitat for Humanity Natural History Museum - Utah Washington Capitals ICF International NBC Sports Yelp Institutions representing Bachelor’s degrees DIVERSITY OF GRADUATE SCHOOLS – a wide range of schools 946 American University* Savannah College of Art & Design awarded to CAL graduates Bowling Green State University Temple University Cambridge University University of Edinburgh Drexel University University of Florida George Mason University* University of Maryland 427 George Washington University* University of Pittsburgh unique employers Georgetown University University of St. -

Red Nose Day Complaints

Red Nose Day Complaints Dissonant Ephrem sometimes discept any plaids don satanically. Kinetically sparoid, Christof stage-manages strap-hinge and scarify Filipinos. Bart is potentially resolved after repugnant Wendall truss his spherocyte longest. If you can children with the longest ever quit comic relief us to save lives due to inpatients in red nose day in hand to make changes to power services While in school Hannah interned at Pirate Radio Station, WNCT, NBC News Channel and WITN. Reverse the nose with our communities together the clear. Being a beanpole is a very least order! Treatment of red nose day complaints over a reasonable time! Red iron Day 2017 Page 13 TV Forum. Comic Relief might be investigated by Ofcom as complaints. Set up the search. Sets render the day is currently supported browsers in south carolina university of canterbury, and dry and mine of text transform in america. Woman dies after explosion destroys house in Greater Manchester leaving one woman now a deliver in. David Baddiel as he unloaded supplies at one point. No Plans for half term this week. MNT is the registered trade mark of Healthline Media. Nose is clearly dependent on and complaints it mean to a tv in los angeles donut recipe for red nose day complaints or all over the small commission for this. However, the overall evidence of benefits for hair health is limited. Listeners are invited to always tune in january the complaints procedure and sensitive information for any assistance, red nose day complaints over the audience. We all try to address all your concerns promptly, provide you edit an explanation and dedicate any flour that easily be needed to prevent many future occurrence. -

To Download The

Dr. Erika R. Hamer Dr. Erika R. Hamer DC, DIBCN, DIBE DC, DIBCN, DIBE Board Certified Board Certified Chiropractic Neurologist Chiropractic Neurologist Practice Founder/Owner Practice Founder/Owner Family Chiropractic Care Family Chiropractic Care in Ponte Vedra Beach & Nocatee Town Center in Ponte Vedra Beach & Nocatee Town Center Dr. Erika R. Hamer Dr. Erika R. Hamer DC, DIBCN, DIBE NOCATEE Initial Visit and Exam DC, DIBCN, DIBE NOCATEE Initial Visit and Exam Board Certified Initial Visit and Exam - Valued at $260! Board Certified Initial Visit and Exam - Valued at $260! Chiropractic Neurologist RESIDENT Valued at $260! Chiropractic Neurologist RESIDENT Valued at $260! Practice Founder/Owner SPECIAL *Offer alsoalso valid valid for for reactivating reactivating patients - those not Practice Founder/Owner SPECIAL *Offer alsoalso valid valid for for reactivating reactivating patients - those not Family Chiropractic Care seenpatients at the- those office not in seen the at previous the office six months. Family Chiropractic Care seenpatients at the- those office not in seen the at previous the office six months. Serving St. Johns County for 17 Years in the previous six months. Serving St. Johns County for 17 Years in the previous six months. www.pontevedrawellnesscenter.com In Network for Most Insurance Companies www.pontevedrawellnesscenter.com In Network for Most Insurance Companies Nocatee Town Center/834-2717 205 Marketside Ave., #200, Ponte Vedra, FL 32081 Nocatee Town Center/834-2717 205 Marketside Ave., #200, Ponte Vedra, FL 32081 Most Insurance -

2020 Annual Report | Together We Are Feeding America

TOGETHER W E ARE FEEDING AMERICA PG 1 ANNUAL REPORT 20 20 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2020 ANNUAL REPORT MOTIVATION MISSION IMPACT 3 5 9 FINANCIALS 27 SUPPORTERS 30 LEADERSHIP 67 PG 2 MOTIVATION 2020 ANNUAL REPORT MEET ELENA On a hot summer morning, Elena Martinez, along with her sons—Kevin, 4 and Adonay, 2—arrived at a food pantry that works with Capital Area Food Bank, a member of the Feeding America network. Before the impact of COVID-19, Elena worked in a restaurant kitchen. Due to the economic fallout from the pandemic, she— like tens of millions of people across the country—lost her job. As Elena saw the nutritious food available for her to take home to help feed her family of seven, she smiled, excited about the meals she could prepare amid a devastating time of unemployment and uncertainty. Women like Elena are overrepresented in some of the hardest-hit industries for job loss, including leisure and hospitality, healthcare and education, and women—especially “ Black and Latino women—lost jobs in those sectors I’M VERY at disproportionate rates. GRATEFUL TO GOD THAT MY FAMILY IS ABLE TO EAT BECAUSE OF THE FOOD THAT I RECEIVE FROM THE PANTRY. ” PG 3 MOTIVATION 2020 ANNUAL REPORT MEET OUR VOLUNTEERS Before the pandemic, the Feeding America food bank network relied on the generous time of nearly 2 million volunteers each month. The impact of COVID-19 quickly shattered that. Adhering to shelter- in-place orders, social-distancing protocols and health concerns, food banks saw a 60% decline in this critical volunteer workforce. -

COMIC RELIEF USA 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report | Comic Relief USA

COMIC RELIEF USA 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report | Comic Relief USA LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN 2017 was a significant year in the evolution of Comic Relief USA. We continued to lay the foundations for a successful future and furthered our work to make a difference in the lives of so many children in America and around the world. This year marked the delivery of a third, hugely successful Red Nose Day USA—with record breaking income—and proved the mettle of the team as they took on a new challenge in response to the devastating hurricanes in Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico. For the first time, this year’s Red Nose Day campaign saw almost all of our core operational, marketing and KEVIN leadership roles filled by a full-time permanent staff based out of our New York offices—a shift which marks CAHILL a real “passing of the baton” from the Comic Relief UK team. We have made great strides in developing our policies and procedures to help the team to work most effectively with each other, our corporate and grantee partners, and the UK organization. We are so grateful for all of the excellent support the Comic Relief UK team has provided as we initially built up operations in the US. Their experience and knowledge has been invaluable. At the end of such a successful and important year for the organization, I am sad to say that I am stepping down as the Chair of the Board after 11 years, though I am staying on for a while as a member of the Board of Directors to support the transition process. -

Feeding America's 2020 Annual Report

TOGETHER W E ARE FEEDING AMERICA PG 1 ANNUAL REPORT 20 20 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2020 ANNUAL REPORT MOTIVATION MISSION IMPACT 3 5 9 FINANCIALS 27 SUPPORTERS 30 LEADERSHIP 67 PG 2 MOTIVATION 2020 ANNUAL REPORT MEET ELENA On a hot summer morning, Elena Martinez, along with her sons—Kevin, 4 and Adonay, 2—arrived at a food pantry that works with Capital Area Food Bank, a member of the Feeding America network. Before the impact of COVID-19, Elena worked in a restaurant kitchen. Due to the economic fallout from the pandemic, she— like tens of millions of people across the country—lost her job. As Elena saw the nutritious food available for her to take home to help feed her family of seven, she smiled, excited about the meals she could prepare amid a devastating time of unemployment and uncertainty. Women like Elena are overrepresented in some of the hardest-hit industries for job loss, including leisure and hospitality, healthcare and education, and women—especially “ Black and Latino women—lost jobs in those sectors I’M VERY at disproportionate rates. GRATEFUL TO GOD THAT MY FAMILY IS ABLE TO EAT BECAUSE OF THE FOOD THAT I RECEIVE FROM THE PANTRY. ” PG 3 MOTIVATION 2020 ANNUAL REPORT MEET OUR VOLUNTEERS Before the pandemic, the Feeding America food bank network relied on the generous time of nearly 2 million volunteers each month. The impact of COVID-19 quickly shattered that. Adhering to shelter- in-place orders, social-distancing protocols and health concerns, food banks saw a 60% decline in this critical volunteer workforce. -

2018 Annual Report | Solving Hunger Today, Ending Hunger Tomorrow

2018 ANNUAL SOLVING HUNGER TODAY REPORT ENDING HUNGER TOMORROW CONTENTS MEET LAMONT ...................................................................... 3 A MESSAGE FROM OUR PRESIDENT AND BOARD CHAIR .................................. 4 IMPACT .................................................................................... 5 FINANCIALS .........................................................................19 SUPPORTERS ...................................................................... 22 LEADERSHIP .......................................................................46 FEEDING AMERICA ANNUAL REPORT 2 MEET LAMONT “Igrewupinpoverty,andIsworethatmyfamilywouldnever THANKS gothroughwhatIdid.So,Ichasedthedollar—workedday TO YOU, inanddayouttoprovide.ButthenIgothurtatwork,and itallfellapart. Lamont’s family has the meals they need. Ididnotwanttovisitafoodpantry.Ihadpromisedmyself thatIwouldneverbeinapositionwhereIcouldn’tprovide formyfamily.ButthereIwas,withoutworkandwithoutfood. WATCH Mywifetookituponherselftogotothepantrybecausewe THEIR STORY hadkidstofeed.ShebegantoinsistIgowithher.Idid,and mylifechanged. Ibegantovolunteeratthepantry.Theysawsomething inme,andsoon,theyhiredme.Iwaslaterpromotedto adirector,andnowI’minchargeofaprogramthatworks withfamiliestobreakthecycleofpoverty.Icanprovidefor myfamilyagain,andnotonlythat,I’mtrulyfulfilled. IknowI’mmakingabigdifferenceinpeople’slives. Therearesomanyothersouttherewaitingtoachieve similarsuccess,theyjustneedalittleextrahelptogetthere. I’mcommittedtohelpingasmanypeopleasIcanfeedtheir -

Altruism, Empathy, and Efficacy: the Science Behind Engaging Supporters

ALTRUISM, EMPATHY & EFFICACY 0 ALTRUISM, EMPATHY & EFFICACY ALTRUISM, EMPATHY & EFFICACY ABOUT THE PUBLISHER Georgetown University’s Center for Social Impact Communication (CSIC) is a research and action center dedicated to increasing social impact through the power of marketers, communicators, fundraisers and journalists working together. As part of the University’s School of Continuing Studies, the Center accomplishes its mission of educating and inspiring practitioners and students through applied research, graduate courses, community collaborations and thought leadership. To contact the Center, please email [email protected] or visit us online at http://csic.georgetown.edu/. ABOUT THIS GUIDE What you have in your hands is part applied literature review and part hypothesis on how we can better motivate audiences to support nonprofit causes, using the research of social scientists and the experience of social impact practitioners alike. Social impact practitioners can take many forms. They can be fundraisers working at a nonprofit or social marketers working on one of the many government-funded behavior change programs. They can be communicators working for socially-driven companies or even journalists working for cause-driven media outlets. But ultimately this guide is designed to help you—under whatever label best suits you— to make better decisions in how to talk to your supporters. The social impact space, much like the marketing and communications industry at large, is filled with cautionary tales from “gut” marketers who make decisions based on what they think will work best, instead of what we know will work best based on the science of human behavior and the measuring of past performance. -

Results for Children: Annual Report 2017

RESULTS FOR CHILDREN 2017 ANNUAL REPORT WHAT EVERY CHILD DESERVES At the very heart of who we are and all we do for children is this essential truth, expressed so fervently by our founder, Eglantyne Jebb, “Humanity owes the child the best it has to give.” That’s why we’re passionately committed to giving the world’s children, especially those most vulnerable, what every child deserves – a healthy start in life, the opportunity to learn and protection from harm. Whatever it takes. Thanks to amazing supporters like you, we’re ever closer each year to achieving our ambitions. We’re forging key partnerships, piloting innovative solutions, advocating for best policies – and together, achieving remarkable results at scale. In 2017 alone, we reached more than 155 million children in 120 countries around the world, including 237,000 right here in the United States. Transforming their lives and the future we share. We invite you to take this opportunity to review the results for children you helped make possible. We’ll also show you how effectively we stewarded the significant resources required to achieve them. And we ask for your continued support of our shared cause. Because the world’s children deserve our very best. Every last child. Thank you, INSIDE Carolyn Miles Dr. Jill Biden President & CEO Chair, Save the Children Board of Trustees 3 2017: The Big Picture @carolynsave @SCUSBoardChair @thecarolynmiles 5 Our Global Results 21 Our U.S. Results 29 Our Innovations 33 Our Valued Partners 41 Our Leadership 43 Our Financials For 2017 results and much more, go to SavetheChildren.org/RESULTS.