Journal of International Academic Research for Multidisciplinary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Factors of Christianizing the Erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940)

Mizoram University Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (A Bi-Annual Refereed Journal) Vol IV Issue 2, December 2018 ISSN: 2395-7352 eISSN:2581-6780 Cultural Factors of Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940) Zadingluaia Chinzah* Abstract Alexandrapore incident became a turning point in the history of the erstwhile Lushai Hills inhabited by simple hill people, living an egalitarian and communitarian life. The result of the encounter between two diverse and dissimilar cultures that were contrary to their form of living and thinking in every way imaginable resulted in the political annexation of the erstwhile Lushai Hills by the British colonial power,which was soon followed by the arrival of missionaries. In consolidating their hegemony and imperial designs, the missionaries were tools through which the hill tribes were to be pacified from raiding British territories. In the long run, this encounter resulted in the emergence and escalation of Christianity in such a massive scale that the hill tribes with their primal religious practices were converted into a westernised reli- gion. The paper problematizes claims for factors that led to the rise of Christianity by various Mizo Church historians, inclusive of the early generations and the emerging church historians. Most of these historians believed that waves of Revivalism was the major factor in Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills though their perspectives or approach to their presumptions are different. Hence, the paper hypothesizes that cultural factors were integral to the rise and growth of Christianity in the erstwhile Lushai Hills during 1890-1940 as against the claims made before. Keywords : ‘Cultural Factors of Conversion,’ Tlawmngaihna, Thangchhuah, Pialral, Revivals. -

Rohmingmawii Front Final

ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM (A UGC Notified Journal) Vol. XVIII Revisiting Mizo Heroes Mizo History Association September 2017 The main objective of this journal is to function as a mode of information and guidance for the scholars, researchers and historians and to provide a medium of exchange of ideas in Mizo history. © Mizo History Association, 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this journal may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. ISSN : 0976 0202 Editor Rohmingmawii The views and interpretations expressed in the Journal are those of the individual author(s)’ and do not necessearily represent the views of the Editor or Mizo History Association. Price : Rs. 150/- Mizo History Association, Aizawl, Mizoram www. mizohistory.org Printed at the Samaritan Printer Mendus Building, Mission Veng, Aizawl ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM Vol. XVII (A UGC Recognised Journal) September 2017 Editor Rohmingmawii Assistant Professor Department of History Pachhunga University College, Aizawl MIZO HISTORY ASSOCIATION: AIZAWL Office Bearers of Mizoram History Association (2015 – 2017) President : Prof. Sangkima, Ex-Principal, Govt. Aizawl College Vice President : Prof. JV Hluna, Pachhunga University College Secretary : Dr. Benjamin Ralte, Govt. T Romana College Joint Secretary : Dr. Malsawmliana, Govt. T Romana College Treasurer : Mrs. Judy Lalremruati, Govt. Hrangbana College Executive Committee Members: Prof. O. Rosanga, Mizoram University Mr. Ngurthankima Sailo, Govt. Hrangbana College Prof. C. Lalthlengliana, Govt. Aizawl West College Dr. Samuel VL Thlanga, Govt. Aizawl West College Mr. Robert Laltinchhawna, Govt. -

September, 2019

September 2019 Ramthar 1 www.mizoramsynod.org September 2019 Ramthar 2 www.mizoramsynod.org September 2019 Ramthar 3 I BEI RUAL ANG U Editorial Nikum 2018 khán Beihrual Centenary hlim takin kan hmang a. Kumin hi Beihrual kum 101-na lai a lo tling leh ta. Beihrual hmangtu zawng zawngte Ramthar Editorial Board member-ten Pathian hmingin chibai kan bûk che u a, duhsakna kan hlàn nghâl bawk a che u. Ringtu hmasate kha ‘Pathian thuâwih’ tiin sawi an ni \hìn a. Hei hian Pathian mi an nih bâkah a thu zàwmtute an nih a hril nghâl bawk. Ringtu hmasate kha chuan sual leh thil \ha lo an hriat apiang kalsanin Isua an ring bur mai a ni. Chu chuan an nun a tihlim êm êm a; sual hmachhawn tùr pawh ni se, an hlau lo va, an zâm ve mai ngai lo. Chanchin |ha neitu chu hril duhna leh châknain a khat \hìn. Lal Isuan, “Khaw dangah te pawh Pathian Ram Chanchin |ha ka hril tùr a ni; chumi avàng chuan tirh ka ni si a,” (Lk 4:43) a tih angin, an chhúngte leh an khaw \henawmte an vei a. An hmuh leh hriat chu chang ve se an ti; ‘Fangrual Pawl’ te awmin a huhovin khaw hlá leh hnaiah Chanchin |ha chu an feh chhuahpui \hìn. Mizoten Chanchin |ha kan hrilna ram mite hi anmahni hnam invei zui apiangten an vànneihpui tlángpui. Chanchin |ha hrilh buaipui lo - mi mal, chhúngkua, kohhran, ram leh hnam chuan a aia \angkai lo leh \ha lo zâwk thil dang an buaipui tho tho va, an nunin a chhiatphah \hìn. -

C:\Documents and Settings\All U

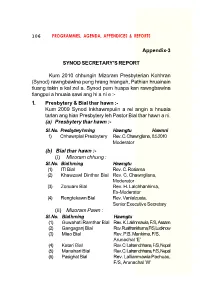

106 PROGRAMMES, AGENDA, APPENDICES & REPORTS Appendix-3 SYNOD SECRETARY’S REPORT Kum 2010 chhungin Mizoram Presbyterian Kohhran (Synod) rawngbawlna peng hrang hrangah, Pathian hruainain tluang takin a kal zel a. Synod pum huapa kan rawngbawlna tlangpui a hnuaia sawi ang hi a ni e :- 1. Presbytery & Bial thar hawn :- Kum 2009 Synod Inkhawmpuiin a rel angin a hnuaia tarlan ang hian Presbytery leh Pastor Bial thar hawn a ni. (a) Presbytery thar hawn :- Sl. No.Presbytery hming Hawngtu Hawnni 1) Chhawrpial Presbytery Rev. C. Chawngliana,8.5.2010 Moderator (b) Bial thar hawn :- (i) Mizoram chhung : Sl. No.Bial hming Hawngtu (1) ITI Bial Rev. C. Rosiama (2) Khawzawl Dinthar BialRev. C. Chawngliana, Moderator (3) Zonuam Bial Rev. H. Lalchhanhima, Ex-Moderator (4) Rengtekawn Bial Rev. Vanlalzuata, Senior Executive Secretary (ii) Mizoram Pawn : Sl. No.Bial hming Hawngtu (1) Guwahati Ramthar BialRev. K. Lalrinmawia, F/S, Assam (2) Gangaganj Bial Rev. Rualthankhuma, F/S, Lucknow (3) Miao Bial Rev. P.B. Mankima, F/S, Arunachal ‘E’ (4) Katari Bial Rev. C. Lalramchhana, F/S, Nepal (5) Manahari Bial Rev. C. Lalramchhana, F/S, Nepal (6) Pasighat Bial Rev. Lallianmawia Pachuau, F/S, Arunachal ‘W’ PROGRAMMES, AGENDA, APPENDICES & REPORTS 107 (7) Chakmaghat Bial Rev. C. Zorammawia, F/S, Tripura (8) Tuingoi Bial Rev. Ralthansanga Ralte, A/ S, Barak Area 2. Pastor leh Pro. Pastor Induction :- Synod Inkhawmpui 2009-in a rel angin Pastor thawklai, Nemngheh thar te leh Pro. Pastor lak tharte an vaiin an awmna turah 17th January, 2010 khan tluang taka dahngheh (induct) vek an ni a. Pastor zirna sang zawka zir, April 2010-a zir zote pawh 9th May 2010-ah an awmna turah dahngheh (induct) vek an ni bawk. -

Generating Knowledge on Lushai Hills: the Works of T.H Lewin

Mizoram University Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (A Bi-Annual Refereed Journal) Vol IV Issue 2, December 2018 ISSN: 2395-7352 eISSN:2581-6780 Generating Knowledge on Lushai Hills: The Works of T.H Lewin H.Vanlalhruaia* Ramdinsangi** Abstract The main objective of this paper is to situate colonialism and European ethnographic practices in the process of Mizo history making in the second half of nineteen century Lushai Hills. Until the appointment of T.H Lewin [Thangliana] (1839-1916) as Deputy Commissioner of Hill Tract, the British had little knowledge on the details of the Mizos and their cultural history. He was appointed to confront the problem of how to come to terms with the Mizo (Lushai and Shendu) chiefs who were constantly “hostile” to the British. Lewin early career in India was describe by himself in his ethnographic text “A fly on the Wheel or How I helped to Govern India” published in 1885. The work of T.H Lewin has been described extensively in Mizo literary circles –mostly his contributions toward the Mizo society in a straightforward manner. He has been often portrayed as a paternalist figure of Mizo society. One of the main objectives of this paper is to inject further discussion and debate on his European background and his love for the Mizo people in the course of colonial territorial- making in North East India. Key Words: Knowledge, Colonial, Ethnography, Tribe, Lushai, European, Paternalist The main objective of this paper is to generated and produced throughout their situate colonialism and European association with the Mizos. Particularly ethnographic practices in the process of from the second half of the nineteenth Mizo history making in the second half century, Lushai Hills becomes – what of nineteenth century Lushai Hills. -

Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan Serchhip District

SARVA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN SERCHHIP DISTRICT DISTRICT ELEMETARY EDlfCATION PLAN SERCHHIP DISTRICT, MIZORAM Prepared by : District Unit of The SSA Mission, Serchhip District, Mizoram SARVA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN DISTRICT El.EM El ARY EDUCATION PLAN SERCHHrP DISTRICT, MIZORAM Prepared by : District Unit of The SSA Mission, Serchhip District, Mizoram J a MAP OF SI fiC DISIHIC AIZAWL DISTRIC I V #Khumtung Hniawngkawn # # Baktawng •H iiaitu i •Buhkangkawn jj #Hmunth<-3 Chfiingchhip - . - . #Khawtjel. 'Vanchehgpui' U •ih en tlan g 5 H Rullam CD ^hhiahtlang Liinqpho Sialhau < X NuentiatigJue Cl 0 New Serchhip 9 < #Vanchengte X Neihloh % i hinglian O SERCHHIP HriangtTang Hmunzawl Thenzawl Buangpui Piler Khawlailung Chekawn I E. Lunadc I #Bu(igtlang Mualcheng* "X I eng# i3 Sialsir sta\jwktlang^ . Lungchhuan ^ Sailulak N. Vanlaiphai i ' l u n (; le I D isxm cT Luj^gkawlh g sru cu n ip DISl RICT AT A CLAI\(T- I Name olDistrirl Serclihip 2. Niiine ol hetidqiiaitcrs Serchhip V Areas 1372,61 Sq, Kin. (Approx ) I - Total I’opiilalioii S5539 ii)JJii)aii ()p()iil.ati.oij 29-206................................. (ii) Rural population 26333 5 I iteracy ))ercentage 96 1 7% 6. Density 0r|)0|)ula(J0n 47 per S(j Km. 7. No of villages/habitations 38 8 No of towns 3 9 (i) No. of Pnniaiy Sch()ols private) 98 (li) No. of Upper lYimaiy Schools {Incl. private) 68 (iii) No of liS’s (Including Private) 23 (iv)No. ofHSS’s 2 (v) No. of College 10. No. of Educational Clusters : 12 1 I. No. of Educational Circles 12. No of Bducalional Sub-Division 13, No of Rural Development IMocks 14 No of Civil Sub-Divisions INDKX C hapler Con(ents Page No. -

HERALD of MISSIONARIES and Bran

HERALD C A POLICEMAN'S LOT IS NOT A HAPPY ONE The Baptist Church in Mizoram ................................................................ PAST FOLLIES AND 1-DGH TECHNOLOGY Health care in Guinea ................................................................................ Cover photograph: Tirana, Albania 0 SIXTEEN WAYS TO SAY FRIEND First impressions ofAlbania ...................................................................... DAY TRIP TO BOLOBO A visit to an oil palm plantation................................................................. 8 N OF MISSIONARIES AND BRAN Language study in Belgium ........................................................................ 10 DOUBLE TAKE Taking a second look at language and culture ........................................... 11 QUIET AGAIN T Another report from Kinshasa .................................. :................................ .. 15 A FOOTNOTE IN HISTORY Ten years as BMS minutes secretary ........................................................... 16 CALL TO PRAYER E Updating the BMS Prayer Guide ............................................................... 17 NEWS Missionaries' Literature Association, Angola ............................................. 18 IN VIEW N More news from home and overseas............................................................ 2 0 CHECKOUT Missionaries' travel and gifts to the Society ................................................ 21 MAKING WAVES T Liberation theology in Britain ................................................................... -

7. Contemporary Kuki Artists

P a g e | 181 7. CONTEMPORARY KUKI ARTISTS 7.1. INTRODUCTION The term “contemporary” is derived from the Latin word “contemporaries” which means a person or thing existing at the same time as another. The Cambridge School Dictionary defines it as ‘existing or happening at the same time as something of the present time’. In 1910, the contemporary Art Society was founded in London by the critic Roger Fry. Contemporary art is an art that persist at the same time or ones’ lifetime. Shelley Esaak (Esaak) in About.com argued that modern art was from the impressionist age up to the 1960s or 70s, and that of contemporary starts from 1960s or 1970s. About.com Art History further argued 1970 as the cut-off for two reasons. First, because it was around 1970 that the terms “Postmodern” and “Postmodernism” popped up-meaning, we must assume, that the art world had its fill of Modern Art starting ring then. Secondly, 1970 seems to be the last bastion of easily classified artistic movements. If you look at the outline of Modern Art, and compare it to the outline of Contemporary Art, you will quickly notice that there are far more entries on the former page.77 According to Wikipedia (Wikipedia), contemporary art is art produced at the present period in time. Contemporary art includes, and develops from postmodern art, which is itself a successor to modern art. In other words modern is the synonym of contemporary. The history of its development continuously grows till date. Wikipedia further gives the list of characteristics of a contemporary artist who fall within four criteria (Wikipedia): • The person is regarded as an important figure or is widely cited by his/her peers or successors. -

Volume X – 1 Summer 2018

i CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL SCIENTIST (A National Refereed Journal) Vol :X-1 Summer 2018 ISSN No: 2230 - 956X SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY (A Central University) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA ii iii CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL SCIENTIST (A National Refereed Journal) Vol :X-1 Summer 2018 ISSN No: 2230 - 956X Prof. Zokaitluangi Editor in Chief Dean, School of Social Sciences, Mizoram University & Professor, Department of Psychology, MZU SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MIZORAM UNIVERSITY (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA e-mail : [email protected] iv v CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL SCIENTIST (A National Refereed Journal) Vol :X-1 Summer 2018 ISSN No: 2230 - 956X School of Social Editors Sciences- Convergence Editors Patron: Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University, Aizawl, India Guidelines Editor in Chief: Professor Zokaitluangi, Dean , Shool of Social Sciences, Mizoram University, Aizawl, India Archives (hard copy) Editorial boards: Prof. J.K. PatnaikDepartment of Political Science, MZU Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Head Department of Public Administration, MZU Vol: I - 1 Prof. O. Rosanga, Department of History & Ethnography, MZU Vol: I - 2 Prof. Lalrintluanga, Department of Public Administration, MZU Vol: II - 1 Prof. Lalneihzovi, Department of Public Admn, MZU Vol: II - 2 Prof. C. Lalfamkima Varte, Head, Dept. of Psychology, MZU Vol: III - 1 Prof. H.K. Laldinpuii Fente, Department of Psychology, MZU Vol: III - 2 Prof. E. Kanagaraj, Department. of Social Work, MZU Vol: IV - 1 Prof. J. Doungel, Department of Political Science, MZU Vol: IV - 2 Prof. C. Devendiran, Head, Department of Social Work, MZU Vol: V - 1 Vol: V - 2 Prof. K.V. Reddy, Head, Department of Political Science, MZU Vol: VI - 1 Dr. -

SWBTS Style Template

The Impact of Christian Missions and Colonization in Northeast India and Its Role in the Tribal Nation-Building Movement A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Roy Fish School of Evangelism and Missions Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ministry by Albert Yanger December 2017 Copyright © 2017 Albert Yanger All rights reserved. Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation, or instruction. APPROVAL SHEET THE IMPACT OF CHRISTIAN MISSIONS AND COLONIZATION IN NORTHEAST INDIA AND ITS ROLE IN THE TRIBAL NATION-BUILDING MOVEMENT Albert Yanger John Massey, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Missions, Advisor Matt Queen, Ph.D., L.R. Scarborough Chair of Evangelism (“Chair of Fire”), Associate Professor of Evangelism, and Associate Dean for Doctoral Programs Date Dedicated to my wife, Bano and daughter Amy, who have encouraged and stood by me throughout my studies. Also, to my professors at SWBTS and the brothers and sisters in Christ at FCBC. Abstract The Impact of Christian Missions and Colonization in Northeast India and Its Role in the Tribal Nation-Building Movement Christian missions had a huge impact in the Northeastern region of India. This impact, combined with western (British) colonization, produced a synergy that changed the entire landscape of the Northeast. This dissertation focuses on the social and political aspects of that change. The primary catalyst was the translation of the Bible into local languages, and a highly successful education program that every mission and denomination implemented from the very beginning. -

Geography of Indo-Myanmar Boundarywith Special Reference to Mizoram: an Analytical Study

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Geography of Indo-Myanmar boundarywith special reference to Mizoram: An Analytical study *LalmalsawmaRalte. **Prof.Vishwambar Prasad Sati Assistant Professor Department of Geography Government Hrangbana College Mizoram University Abstract The main objectives of the present study are: (i) to identify the basis of evolution of Indo-Myanmar boundary with reference to Mizoram (ii) to examine the geographical basis of Indo-Myanmar boundary with reference to Mizoram (iii) to study the Eastern Boundary of Mizoram (South to North) and (iv) to study the Southern Boundary of Mizoram : Mizoram – Myanmar (West to East).The geographical location of Mizoram is of great significance and forms an ideal field of geographical study. Mizoram shares international borders with Myanmar in the east and south (404 km) and Bangladesh in the west (306 km). This has divided the Mizo’s and their associated clans. It has a complex north-south trending mountainous terrain which is thickly forested. Along with its inaccessible and isolated nature, the southern margins and the trijunction points(Mizoram – Tripura – Assam, Mizoram – Manipur – Assam, Mizoram – Bangladesh – Tripura and Mizoram – Myanmar – Bangladesh ) have formed an important core of activities at the time of insurgency. This is the reason why this frontier has attained strategic and geopolitical significance. Keyword: Indo-Myanmar, Boundary, Eastern Boundary of Mizoram, Southern Boundary of Mizoram INTRODUCTION The term ‘boundaries’ are often used interchangeably with frontiers. In fact, boundaries are lines demarcating the outer limits of territory under the sovereign jurisdiction of a Nation-State. It implies the physical limit ofa sovereignty and jurisdiction of a state. -

Political History of Lushai Hills Since the Pre-Colonial Era

Vol. VI, Issue 1 (June 2020) http://www.mzuhssjournal.in/ Political History of Lushai Hills since the Pre-Colonial Era R. Vanlalhmangaihsanga * Abstract Mizo tribes had never been placed under the rule of any governing body during the pre- colonial era. However, raids upon plain areas and capturing of slaves compelled the British Government to carry out the First Lushai Expedition (1871-72) in the hope of subduing the barbaric Mizo chiefs. This Expedition tamed the Mizo chief to a certain extend, however, the Mizo chiefs went back to their old ways and started invading their neighboring lands which led to the second expedition known as Chin- Lushai Expedition in 1889 which subsequently led to British colonization of the Lushai Hills. Chin- Lushai Expedition occurred in 1889-1890 during which the British colonized the whole of Chin Hills and Lushai Hills. British colonized the Lushai Hills for almost 40 years and Lushai Hills remain in India after independence. The issue of whether or not the Mizos joined the Indian Union in their own accord is still an ongoing debate even in the present days. Keywords : Mizo Tribes, British Colonization, Chiefs, Expedition, Tribal Area. There are various theoretical concepts on the origin of the Mizo Tribes. Most of the Mizo historians believed that the Mizo tribes originated from ‘Chhinlung’. However, the precise origin of ‘Chhinlung’ cannot be determined although southern part of China has been the most accepted concept (Sangkima, 2004). It was believed that Mizo tribes entered Chin Hills during the 14 th century and settled there till the late 16 th century.