ABSTRACT Dynamics of Christianity in Select Mizo Folk Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Lunglei District

DISTRICT AGRICULTURE OFFICE LUNGLEI DISTRICT LUNGLEI 1. WEATHER CONDITION DISTRICT WISE RAINFALL ( IN MM) FOR THE YEAR 2010 NAME OF DISTRICT : LUNGLEI Sl.No Month 2010 ( in mm) Remarks 1 January - 2 February 0.10 3 March 81.66 4 April 80.90 5 May 271.50 6 June 509.85 7 July 443.50 8 August 552.25 9 September 516.70 10 October 375.50 11 November 0.50 12 December 67.33 Total 2899.79 2. CROP SITUATION FOR 3rd QUARTER KHARIF ASSESMENT Sl.No . Name of crops Year 2010-2011 Remarks Area(in Ha) Production(in MT) 1 CEREALS a) Paddy Jhum 4646 684716 b) Paddy WRC 472 761.5 Total : 5018 7609.1 2 MAIZE 1693 2871.5 3 TOPIOCA 38.5 519.1 4 PULSES a) Rice Bean 232 191.7 b) Arhar 19.2 21.3 c) Cowpea 222.9 455.3 d) F.Bean 10.8 13.9 Total : 485 682.2 5 OIL SEEDS a) Soyabean 238.5 228.1 b) Sesamum 296.8 143.5 c) Rape Mustard 50.3 31.5 Total : 585.6 403.1 6 COTTON 15 8.1 7 TOBACCO 54.2 41.1 8 SUGARCANE 77 242 9 POTATO 16.5 65 Total of Kharif 7982.8 14641.2 RABI PROSPECTS Sl.No. Name of crops Area covered Production Remarks in Ha expected(in MT) 1 PADDY a) Early 35 70 b) Late 31 62 Total : 66 132 2 MAIZE 64 148 3 PULSES a) Field Pea 41 47 b) Cowpea 192 532 4 OILSEEDS a) Mustard M-27 20 0.5 Total of Rabi 383 864 Grand Total of Kharif & Rabi 8365 15505.2 WATER HARVESTING STRUCTURE LAND DEVELOPMENT (WRC) HILL TERRACING PIGGERY POULTRY HORTICULTURE PLANTATION 3. -

Vol III Issue I June2017

Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) MIZORAM UNIVERSITY NAAC Accredited Grade ‘A’ (2014) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA i . ii Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Chief Editor Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama Editor Prof. J. Doungel iii Patron : Prof. Lianzela, Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University Advisor : Mr. C. Zothankhuma, IDAS, Registrar, Mizoram University Editorial Board Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Dept. of English, Chief Editor Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Dept. of Public Administration, Member Prof. NVR Jyoti Kumar, Dept. of Commerce, Member Prof. Lalhmasai Chuaungo, Dept. of Education, Member Prof. Sanjay Kumar, Dept. of Hindi, Member Prof. J. Doungel, Dept. of Political Science, Member Dr. V. Ratnamala, Dept. of Jour & Mass Communication, Member Dr. Hmingthanzuali, Dept. of History & Ethnography, Member Mr. Lalsangzuala, Dept. of Mizo, Member National Advisory Board Prof. Sukadev Nanda, Former Vice Chancellor of FM University, Bhubaneswar Prof. K. Rama Mohana Rao, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. K. C. Baral, Director, EFLU, Shillong Prof. Arun Hota, West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal Dr. Sunil Behari Mohanty, Editor, Journal of AIAER, Puducherry Prof. Joy. L. Pachuau, JNU, New Delhi Prof. G. Ravindran, University of Madras, Chennai Prof. Ksh. Bimola Devi, Manipur University, Imphal iv CONTENTS From the Desk of the Chief Editor vii Conceptualizing Traditions and Traditional Institutions in Northeast India 1 - T.T. Haokip Electoral Reform: A Lesson from Mizoram People Forum (MPF) 11 - Joseph C. -

Ethnobiology in Mizoram State: Folklore Medico-Zoology

Bull.Ind.lnst.Hist.Med. Vol. XXIX - 1999 pp /23 tc 148 ETHNOBIOLOGY IN MIZORAM STATE: FOLKLORE MEDICO-ZOOLOGY H.LALRAMNGHINGLOVA * ABSTRACT Studies in cthnobotany and ethnozoology under the umbrella of Ethnobiology seem imbalanced in the sense that enormous publications have accumulated in case of the former but only little information has been disseminated in case of the latter. While 7500 wild plant species are known to be used by tribals in medicine, only 76 species of animals have been shown as medicinal resources (Anonymous, 1994). The present paper is the first-hand information of folklore medicine from animals in Mizoram. The animals enumerated comprise 01'25 vertebrates and 31 invertebrates and arc used for treatment of over 40 kinds of diseases or ailments, including jaundice, tuberculosis, hepatitis, cancer, asthma and veterinary disease. The author, however, does not recommend destruction of wild animals, he it for food or medicine. Keywords: Folklore medicine, ethnozoology, wildlife, conservation, Mizoram. Introduction operation correlate with their customs and Mizoram is the last frontier of the ceremonies. One of the most important Hirnalyan ranges in the North-East India feasts a Lushai can perform is called and flanked by Bangladesh in the west, 'Khuangchawi' which involved a great deal Myanmar in the east and south, and Assam of money that only the Chiefs or a few we//- in the north. It has a total geographical area to-do people could perform (Parry, 1928). of 21,081 Km ' with a population of A man who performed such ceremony was 6,89,756 persons (census 19(1) and stood called 'Thangchhuah '. -

Mizo Studies Jan-March 2018

Mizo Studies January - March 2018 1 Vol. VII No. 1 January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VII No. 1 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) January - March 2018 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 UGC Journal No. 47167 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl, Mizoram Mizo Studies January - March 2018 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Pioneer to remember - 5 English Section 1. The Two Gifted Blind Men - 7 Ruth V.L. Rinpuii 2. Aministrative Development in Mizoram - 19 Lalhmachhuana 3. Mizo Culture and Belief in the Light - 30 of Christianity Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. Mizo Folk Song at a Glance - 42 Lalhlimpuii 5. Ethnic Classifications, Pre-Colonial Settlement and Worldview of the Maras - 53 Dr. K. Robin 6. Oral Tradition: Nature and Characteristics of Mizo Folk Songs - 65 Dr. -

The “Gospel” of Cultural Sustainability: Missiological Insights

The “Gospel” of Cultural Sustainability: Missiological Insights Anna Ralph Master’s Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at Goucher College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Cultural Sustainability Goucher College—Towson, Maryland May 2013 Advisory Committee Amy Skillman, M.A. (Advisor) Rory Turner, PhD Richard Showalter, DMin Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... iii Chapter One—The Conceptual Groundwork ................................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Definition—“Missiology” .................................................................................................... 4 Definition—“Cultural Sustainability” .................................................................................. 5 Rationale ............................................................................................................................. 7 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 11 Review of Literature—Cultural Sustainability................................................................... 12 Review of Literature—Missiology .................................................................................... -

Cultural Factors of Christianizing the Erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940)

Mizoram University Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (A Bi-Annual Refereed Journal) Vol IV Issue 2, December 2018 ISSN: 2395-7352 eISSN:2581-6780 Cultural Factors of Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940) Zadingluaia Chinzah* Abstract Alexandrapore incident became a turning point in the history of the erstwhile Lushai Hills inhabited by simple hill people, living an egalitarian and communitarian life. The result of the encounter between two diverse and dissimilar cultures that were contrary to their form of living and thinking in every way imaginable resulted in the political annexation of the erstwhile Lushai Hills by the British colonial power,which was soon followed by the arrival of missionaries. In consolidating their hegemony and imperial designs, the missionaries were tools through which the hill tribes were to be pacified from raiding British territories. In the long run, this encounter resulted in the emergence and escalation of Christianity in such a massive scale that the hill tribes with their primal religious practices were converted into a westernised reli- gion. The paper problematizes claims for factors that led to the rise of Christianity by various Mizo Church historians, inclusive of the early generations and the emerging church historians. Most of these historians believed that waves of Revivalism was the major factor in Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills though their perspectives or approach to their presumptions are different. Hence, the paper hypothesizes that cultural factors were integral to the rise and growth of Christianity in the erstwhile Lushai Hills during 1890-1940 as against the claims made before. Keywords : ‘Cultural Factors of Conversion,’ Tlawmngaihna, Thangchhuah, Pialral, Revivals. -

Pseudolaguvia Virgulata, from Mizoram, India

http://sciencevision.info Sci Vis 10 (2), 73 Research Report April-June, 2010 ISSN 0975-6175 On the new catfish, Pseudolaguvia virgulata, from Mizoram, India Lalramliana Department of Zoology, Pachhunga University College, Mizoram University, Aizawl 796001, India A new species of catfish was recently identi- fied from some major rivers of Mizoram. Heok Hee Ng and Lalramliana named the new catfish Pseudolaguvia virgulata, after its distinctively striped colour pattern (virgulata = “striped” in Latin). Besides its distinctive colour pattern, which consists of pale stripes running along the entire length of the body, a pale y-shaped marking on the head and brown stripes running through the caudal fin lobes, the new catfish also differs from congeners in other characters. These in- clude: head width 21.2–24.4% standard length; pectoral-fin length 28.5–29.1% standard length; length of dorsal-fin base 17.2–19.9% standard length; dorsal-spine length 21.5–24.0% standard length; serrated anterior edge of dorsal spine; thoracic adhesive apparatus reaching beyond base of last pectoral-fin ray; body depth at anus 14.5–17.4% standard length; length of adipose- fin base 12.9–15.0% standard length; caudal peduncle length 18.2–20.2% standard length; caudal peduncle depth 7.8–9.7 % standard length; snout length 48.0–54.9% head length; interorbital distance 29.3–35.2% head length; 29 –30 vertebrae. Pseudolaguvia virgulata was collected from river system, one of the three rivers that form clear, shallow, moderately flowing streams with the Ganges Delta. a predominantly sandy bottom. -

Rohmingmawii Front Final

ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM (A UGC Notified Journal) Vol. XVIII Revisiting Mizo Heroes Mizo History Association September 2017 The main objective of this journal is to function as a mode of information and guidance for the scholars, researchers and historians and to provide a medium of exchange of ideas in Mizo history. © Mizo History Association, 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this journal may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. ISSN : 0976 0202 Editor Rohmingmawii The views and interpretations expressed in the Journal are those of the individual author(s)’ and do not necessearily represent the views of the Editor or Mizo History Association. Price : Rs. 150/- Mizo History Association, Aizawl, Mizoram www. mizohistory.org Printed at the Samaritan Printer Mendus Building, Mission Veng, Aizawl ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM Vol. XVII (A UGC Recognised Journal) September 2017 Editor Rohmingmawii Assistant Professor Department of History Pachhunga University College, Aizawl MIZO HISTORY ASSOCIATION: AIZAWL Office Bearers of Mizoram History Association (2015 – 2017) President : Prof. Sangkima, Ex-Principal, Govt. Aizawl College Vice President : Prof. JV Hluna, Pachhunga University College Secretary : Dr. Benjamin Ralte, Govt. T Romana College Joint Secretary : Dr. Malsawmliana, Govt. T Romana College Treasurer : Mrs. Judy Lalremruati, Govt. Hrangbana College Executive Committee Members: Prof. O. Rosanga, Mizoram University Mr. Ngurthankima Sailo, Govt. Hrangbana College Prof. C. Lalthlengliana, Govt. Aizawl West College Dr. Samuel VL Thlanga, Govt. Aizawl West College Mr. Robert Laltinchhawna, Govt. -

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

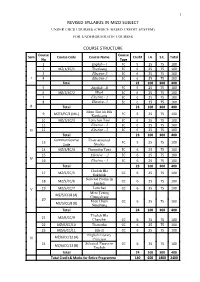

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

E:\Mizo Studies\Mizo Studies Se

Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 783 Vol. VI No. 4 October - December 2017 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 784 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VI No. 4 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) October - December 2017 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 785 CONTENTS Editorial English Section 1. Folk Theatre and Drama of Mizo - Darchuailova Renthlei 2. Impact of Internet Use on the Family Life of Higher Secondary Students of Mizoram - Lynda Zohmingliani 3. The Bible and Study of Literature - Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. English Language: Its Importance & Problems of Learning in Mizoram - Brenda Laldingliani Sailo 5. Theme and Motif of LalthangfalaSailo’s HmangaihVangkhua Play - F. Lalnunpuii Mizo Section 1. Indopui Literature - F. Lalzuithanga 2. R. Zuala Thu leh Hla Thlirna (Literary Works of R. Zuala) - Lalzarzova 786 3. -

2. Executive Summary of Revised Action Plan for 9 Rivers in Mizoram

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ACTION PLAN FOR CONSERVATION OF NINE RIVERS IN MIZORAM, 2019 In compliance of the orders of the Hon’ble NGT on OA No. 673/2018 dt. 20.09.2018, 19.12.2018 & 08.04.2019 Prepared by RIVER REJUVENATION COMMITTEE (RRC) GOVT. OF MIZORAM Contents Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Summary of Action Plan of Tiau River 5 3. Summary of Action Plan of Tlawng River 7 4. Summary of Action Plan of Tuipui River 9 5. Summary of Action Plan of Tuivawl River 11 6. Summary of Action Plan of Chite Stream 13 7. Summary of Action Plan of Mat River 15 8. Summary of Action Plan of Saikah Stream 17 9. Summary of Action Plan of Tuikual River 19 10. Summary of Action Plan of Tuirial River 21 11. Abstract of the financial requirement 23 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ACTION PLAN FOR THE NINE(9) RIVERS OF MIZORAM In compliance to the orders of the Hon’ble NGT dated 20.09.2018, 19.12.2018 & 08.04.2019 in the matter of OA No. 673/2018 - M.C Mehta-Vrs-Union of India & Ors related to the News item dated 17.09.2018, published in ‘‘The Hindu” under the heading “More river stretches are now critically polluted ”, River Rejuvenation Committee (RRC), Govt. of Mizoram has prepared Action Plan for conservation of nine(9) rivers in Mizoram, which are identified to be polluted by CPCB based on BOD level during 2016 and 2017. The nine (9) identified polluted rivers are : i) 1 river (Tiau) - Priority III ii) 3 rivers (Tlawng, Tuipui and Tuivawl) - Priority IV iii) 5 rivers (Chite, Mat, Saikah, Tuikual and Tuirial)- Priority V The Action Plan is prepared for conservation, rather than rejuvenation of the rivers since the identified 9 polluted river stretches in Mizoram are already within the prescribed limits of BOD (Data annexed), preparation of action plan for rejuvenation of these rivers for bringing down the BOD level does not arise for these rivers. -

THE LANGUAGES of MANIPUR: a CASE STUDY of the KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE LANGUAGES OF MANIPUR: A CASE STUDY OF THE KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar Abstract: Manipur is primarily the home of various speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages. Aside from the Tibeto-Burman speakers, there are substantial numbers of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian speakers in different parts of the state who have come here either as traders or as workers. Keeping in view the lack of proper information on the languages of Manipur, this paper presents a brief outline of the languages spoken in the state of Manipur in general and Kuki-Chin languages in particular. The social relationships which different linguistic groups enter into with one another are often political in nature and are seldom based on genetic relationship. Thus, Manipur presents an intriguing area of research in that a researcher can end up making wrong conclusions about the relationships among the various linguistic groups, unless one thoroughly understands which groups of languages are genetically related and distinct from other social or political groupings. To dispel such misconstrued notions which can at times mislead researchers in the study of the languages, this paper provides an insight into the factors linguists must take into consideration before working in Manipur. The data on Kuki-Chin languages are primarily based on my own information as a resident of Churachandpur district, which is further supported by field work conducted in Churachandpur district during the period of 2003-2005 while I was working for the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, as a research investigator.