Handel: the Complete Flute Sonatas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 4-2018 State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First- Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy Tamara Tanner University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Tanner, Tamara, "State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 115. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY by Tamara J. Tanner A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Flute Performance Under the Supervision of Professor John R. Bailey Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2018 STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY Tamara J. Tanner, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2018 Advisor: John R. Bailey During the Baroque flute revival in 1970s Europe, American modern flute instructors who were interested in studying Baroque flute traveled to Europe to work with professional instructors. -

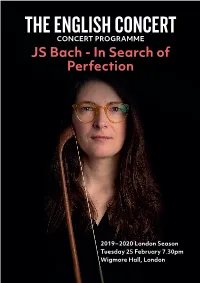

EC-Bach Perfection Programme-Draft.Indd

THE ENGLISH CONCE∏T 1 CONCERT PROGRAMME JS Bach - In Search of Perfection 2019 – 2020 London Season Tuesday 25 February 7.30pm Wigmore Hall, London 2 3 WELCOME PROGRAMME Wigmore Hall, More than any composer in history, Bach The English Concert 36 Wigmore Street, Orchestral Suite No 4 in D Johann Sebastian Bach is renowned Laurence Cummings London, W1U 2BP BWV 1069 Director: John Gilhooly for having frequently returned to his Guest Director / The Wigmore Hall Trust own music. Repurposing and revising it Bach Harpsichord Registered Charity for new performance contexts, he was Sinfonia to Cantata 35: No. 1024838. Lisa Beznosiuk Geist und Seele wird verwirret www.wigmore-hall.org.uk apparently unable to help himself from Flute Disabled Access making changes and refinements at Bach and Facilities Tabea Debus Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D every level. Recorder BWV 1050 Tom Foster In this programme, we explore six of Wigmore Hall is a no-smoking INTERVAL Organ venue. No recording or photographic Bach’s most fascinating works — some equipment may be taken into the Sarah Humphrys auditorium, nor used in any other part well known, others hardly known at of the Hall without the prior written Bach Recorder permission of the Hall Management. all. Each has its own story to tell, in Sinfonia to Cantata 169: Wigmore Hall is equipped with a Tuomo Suni ‘Loop’ to help hearing aid users receive illuminating Bach’s working processes Gott soll allein mein Herze haben clear sound without background Violin and revealing how he relentlessly noise. Patrons can use the facility by Bach switching their hearing aids over to ‘T’. -

1) Musikstunde

__________________________________________________________________________ 2 SWR 2 Musikstunde Dienstag, den 10. Januar 2012 Mit Susanne Herzog Il prete rosso Vivaldi, der Lehrer Kulturinteressierte Venedigreisende haben heutzutage ihren Dumont im Gepäck: damit etwa keine Fragen offen bleiben, wenn man sich angestrengt den Kopf verrenkt, um die Tintoretto Deckengemälde in der Scuola di San Rocco zu bewundern oder um die Details von Tizians Assunta in der Frarikirche zu verstehen. Schon zu Vivaldis Zeiten kamen unglaubliche Mengen an Besuchern nach Venedig: in Stosszeiten soviel wie die Hälfte der Bevölkerung der schwimmenden Stadt. Allerdings nicht nur der kunsthistorischen Schätze wegen, sondern durchaus auch um die Musik Venedigs zu genießen. Und diesbezüglich sprach Vincenzo Coronelli in seinem Reiseführer für Venedig in der Ausgabe von 1706 eine ganz klare Empfehlung aus: „Unter den besseren Geigern sind einzigartig Giovanni Battista Vivaldi und sein Sohn, der Priester.“ Vater und Sohn Vivaldi also galten als Geigenstars. Kaum anders ist es auch zu verstehen, dass Vivaldi mit nur fünfundzwanzig Jahren im Ospedale della Pietà Maestro di Violino wurde. Nicht nur die dortigen Mädchen allerdings kamen in den Genuss seines Unterrichts, sondern schon etablierte Geiger wie etwa der spätere Dresdner Konzertmeister Johann Georg Pisendel nahmen private Geigenstunden bei Vivaldi, um sich zu vervollkommnen. Vivaldi als Lehrer: das ist heute das Thema der SWR 2 Musikstunde. Und dass man nicht nur von einem real anwesenden Lehrer etwas lernen kann, sondern dass auch Noten selbst sprechen, dazu am Ende dieser Stunde noch mehr. 1’25 2 3 Musik 1 Antonio Vivaldi Erster Satz aus Concerto B-dur, RV 368 <16> 3’45 Anton Steck, Violine Modo Antiquo Federico Maria Sardelli Titel CD: Concerti per violino II ‘Di sfida’ Naïve, OP 30427, LC 5718 Privat CD Anton Steck, einer der großen Barockgeiger unserer Zeit hat über dieses Konzert Vivaldis gesagt, da gäbe es Passagen, die würde man eigentlich eher bei Paganini erwarten. -

18-08-01 EVE Zimmermann's Coffeehouse.Indd

VANCOUVER BACH FESTIVAL 2018 wednesday august 1 at 7:30 pm | christ church cathedral the artists zimmermann’s coffee house and garden Soile Stratkauskas George Frideric Handel (1685–1759): flute Trio Sonata Op. 2 no. 1 hwv 386b Beiliang Zhu Andante Allegro ma non troppo cello Largo Chloe Meyers Allegro violin Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–1788): Alexander Weimann 12 Variations on “La Folia d’Espagne” Wq 118:9 harpsichord George Frideric Handel: Sonata Op. 1 no. 7 hwv 365 Larghetto Allegro Double-manual harpsichord Larghetto from the collection of Early Music A tempo di Gavotti Vancouver, built in the mid-70s by Allegro Edward R. Turner of Pender Island after a superb eighteenth-century Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750): instrument by Pascal Taskin, now Violin sonata in E minor bwv 1023 housed in the Russell Collection in Edinburgh. — Adagio ma non tanto Allemande Supported by the Gigue interval Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767): Sonata in G for Flute and Violin (from Der getreue Music-Meister) twv 40:111 Dolce Coffee generously provided by Scherzando Largo e misurato Vivace e staccato Nicola Antonio Porpora (1686-1768): Cello Sonata in F major Pre-concert chat with Largo host Matthew White at 6:45: Allegro Alexander Weimann Adagio Allegro ma non presto Georg Philipp Telemann: Paris Quartet (“Concerto”) in D major twv 43:D1 THE UNAUTHORISED USE OF Allegro ANY VIDEO OR AUDIO RECORDING Affetuoso DEVICE IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED Vivace earlymusic.bc.ca Zimmermann’s Coffee House and Garden Vancouver Bach Festival 2018 1 programme notes by christina hutten Just off the market square, on the most elegant street in Leipzig, a musical master passed through [Leipzig] without getting to step with me under the coloured awnings and through the door know my father and playing for him.” into Herr Zimmermann’s café. -

2011 Charlotte, Nc

3 9 THANNUALNATIONALFLUTEASSOCIATIONCONVENTION OUGH D R IV TH E Y R T S I I T N Y U MANY FLUTISTS, ONE WORLD AUGUST 11–14, 2011 CHARLOTTE, NC Professional flute cases All Wiseman cases are hand made by craftsmen in England fr om the finest materials. All instrument combinations supplied – choose fr om a range of lining colours. Wiseman Cases London 7 Genoa Road, London, SE20 8ES, England [email protected] 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 www.wisemancases.com nfaonline.org 3 4 nfaonline.org cTable of Contents c Letter from the Chair 9 Welcome Letter from the Governor of North Carolina 12 Proclamation from the Mayor of Charlotte 13 Officers, Directors, and Committees 16 Past Presidents and Program Chairs 22 Previous Competition Winners and Commissions 26 Previous Award Recipients 32 Instrument Security Room Information and General Rules and Policies 34 Acknowledgments 36 2011 NFA Lifetime Achievement Awards 40 2011 National Service Award 42 NFA Special Publications 46 General Hours and Information 50 Schedule of Events 51 Programs 78 Guide to Convention Exhibits 200 2011 NFA Exhibitors 201 Exhibit Hall Booth Directory 202 Exhibit Hall and Meeting Rooms Floorplans 203 Westin Hotel Directory 204 NFA Commercial Members Exhibiting in 2011 205 NFA Commercial Members Not Exhibiting in 2011 218 Honor Roll of Donors 219 NFA 2011 Convention Participants 222 Schedule of Events At-a-Glance 273 Index of Music Performed 278 NFA 2012 Convention: Las Vegas, Nevada 300 Competitions for Convention 2012 301 Advertiser Index 304 Please visit nfaonline.org to fill out the post-convention questionnaire. Please address all inquiries and correspondence to the national office: The National Flute Association, Inc. -

The Evolution of the Bassoon and Its Impact Upon Solo

PORTFOLIO OF RECORDED PERFORMANCES AND EXEGESIS: The Evolution of the Bassoon and its Impact upon Solo Repertoire and Performance Emily Clare Stone Submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide November 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE………………………………………………………………………………………..i TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………………………..iii DECLARATION...……………...………………………………………………………………....iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………….…………..v 1 INTRODUCTION….……………………………………………………………………………..1 Recital Programs………………………………………………….……………….………3 2 THE INFLUENCE OF THE RESEARCH ON THE PREPARATION OF THE REPERTOIRE.5 A.Vivaldi: Concerto in E minor F.VIII, No.6……………………………………………..5 G.P. Telemann: Sonata in F minor ………………………………………………………12 W.A. Mozart: Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra KV191.............................................15 F. Devienne: Quartet No. 3, Opus 73 in g minor ……………...………………………...22 C.M.v. Weber: Andante and Hungarian Rondo Op.35….…….....………………………25 E. Elgar: Romance Op.62 ...……..………………………………...…………………….30 A. Tansman: Suite for bassoon and piano.........................................................................32 M. Arnold: Fantasy for bassoon, Op.86.............................................................................35 J. Williams: The Five Sacred Trees...................................................................................36 3 PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT -

Life Members of the British Flute Society Area Representatives

TheJournal of the British Flute Society President James Galway Vice President Albert Cooper Council Area Representatives Douglas Townshend Chairman Helen Baker Avon/Somerset Robert Bigio Events Organizer Carole Timms, 'Marlow', Garston Lane, Blagdon, Avon BS18 Ann Cherry 6TG Tel: 01761 462348 lan Clarke Biiam Jackie Cox Margaret Lowe, 10 Navenby Close, Shirley, Solihull, West Mid- Hugh Pbillips lands B90 ILH Tel: 0121 474 3549 Tessa Ralphson Christine Ring Bolton/Lancashire Susan Mary Whittaker Assistant Area Reps Gwrdinatm Irene Barnes, 40 Grange Park Road, Bromley Cross, Bolton BL7 Julie Wright Area Reps Gwrdinalm/Educafia R@wntaliue 9YA Tel: 01204 59391 1 Cardiff Jenny Wray Membership Secretary Philip Wray Trmm Iau Provis, 13 Werfa Street, Roath Park, Cardiff CF2 5EW Tel: Susan Bnlce Hon Legal Adviror 01222489061 Trevor Wye Archivist East London Kate Cuzner, 52 Turnstone Close, Upper Road, Plaistow, London Judith Fitton Editor Tel: 0171 51 1 5552 The British Flute Society was formed in January 1983 from the constitution: Guildford 'The objects of the Society shall be to advance the education of the public Clare Lund, Down Amphrey, Rowley Drive, Cranleigh, Surrey in the Art and Science of Music and in particular the Art and Science of GU6 8PN Tel: 01483 273167 Flute playing in all aspects by the presentation of public concerts and Hertfordshire recitals and by such other ways as the Society through its Council shall deter- mine from time to time'. Wendy Walshe, Kennel House, Howe Green, Hertford SG13 8LH Tel: 0 1707 261573 The Editor welcomes contributions to Pan - typed and always double spread Leeds - by post to l16 Woodwarde Road, Dulwich, London SE22 8UT (also see Pauline Jackson, Croft Cottage, Old ~ank~o~,~ool-in- Membership Secretary's address). -

Handel Rodelinda

MENU Handel Rodelinda THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET LUCY CROWE | IESTYN DAVIES JOSHUA ELLICOTT | TIM MEAD BRANDON CEDEL | JESS DANDY 1 Credits Tracklist Notes from Harry Bicket Synopsis Programme note Sung texts Handel Rodelinda Biographies THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET LUCY CROWE | IESTYN DAVIES JOSHUA ELLICOTT | TIM MEAD BRANDON CEDEL | JESS DANDY MENU Recorded in St John’s Smith Square, London, Post-production Cover Image UK, Julia Thomas ‘Impossibility’ by on 16–21 September 2020 Francisco Andriani (b. 1989), Italian Language Coach reworked by Recording Producer & Engineer Matteo Dalle Fratte stoempstudio.com Philip Hobbs Design Assistant Engineer stoempstudio.com Rodrigo Leal del Ojo 3 George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) MENU Rodelinda, regina de’ Longobardi, HWV 19 THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET director/harpsichord RODELINDA LUCY CROWE soprano BERTARIDO IESTYN DAVIES countertenor GRIMOALDO JOSHUA ELLICOTT tenor GARIBALDO BRANDON CEDEL bass EDUIGE JESS DANDY contralto UNULFO TIM MEAD countertenor 4 MENU ACT I 1 — Ouverture 4:10 2 — Menuet 1:56 Scene 1 3 — Aria Ho perduto il caro sposo (Rodelinda) 5:38 4 — Recitative Regina! (Grimoaldo, Rodelinda) 0:59 5 — Aria L’empio rigor del fato (Rodelinda) 4:33 Scenes 2 & 3 6 — Recitative Duca, vedesti mai (Grimoaldo, Garibaldo, Eduige) 1:27 Scene 3 7 — Aria Io già t’amai (Grimoaldo) 3:34 Scene 4 8 — Recitative E tu dici d’amarmi? (Eduige, Garibaldo) 0:39 9 — Aria Lo farò (Eduige) 3:41 Scene 5 10 — Recitative Eduige, t’inganni (Garibaldo) 0:24 11 — Aria Di Cupido impiego i vanni (Garibaldo) -

Antonio Vivaldi Concerti

Antonio Vivaldi Concerti Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment Antonio Vivaldi Concerti Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment Concerto in F major for two flutes, two oboes, Concerto in F major for two horns, RV 539 violin, cello and harpsichord 10. Allegro ................................................... 3:15 Il Proteo o sia il mondo al rovescio, RV 572 11. Larghetto .............................................. 2:22 1. Allegro ................................................... 3:44 12. Allegro ................................................... 2:28 2. Largo ..................................................... 2:15 3. Allegro ................................................... 3:37 Andrew Clark & Roger Montgomery horns Lisa Beznosiuk & Neil McLaren flutes, Anthony Robson Concerto in G major for cello, RV 413 & James Eastaway oboes, Margaret Faultless violin, 13. Allegro ................................................. 3:15 David Watkin cello, Paul Nicholson harpsichord 14. Largo ..................................................... 4:03 15. Allegro ................................................ 2:47 Concerto in D minor for oboe and strings, RV 454 David Watkin cello 4. Allegro ................................................. 3:12 5. Largo ....................................................... 2:27 Chamber Concerto in G minor for flute, oboe, 6. Allegro ................................................... 2:37 bassoon, violin and continuo, RV 107 16. Allegro ................................................. 2:22 Anthony Robson -

London Classical Players

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY LONDON CLASSICAL PLAYERS Roger Norrington, Conductor Thursday Evening, October 25, 1990, at 8:00 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan PROGRAM Overture: The Creatures of Prometheus, Op. 43 ... Beethoven Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, Op. 60 Beethoven Adagio, allegro vivace Adagio Allegro vivace Allegro ma non troppo INTERMISSION Symphony No. 3 in A minor, "Scottish" . , Mendelssohn Andante con moto, allegro un poco agitato Vivace non troppo Adagio Allegro vivacissimo, allegro maestoso assai The London Classical Players are represented by Byers, Schwalbe & Associates, Inc., New York. For the convenience of our patrons, the box office in the outer lobby will be open during intermission for purchase of tickets to upcoming Musical Society concerts. To Better Serve Our Patrons Visit the UMS/Encore Information Table in the lobby, where volunteers and staff members are on hand to provide a myriad of details about events, restaurants, etc., and register any concerns or suggestions. Open thirty minutes before each concert and during intermission. Fifth Concert of the 112th Season 112th Annual Choral Union Series Program Notes Overture, Op. 43, Count. The composer had already embarked The Creatures of Prometheus on the Fifth, but laid it aside to compose in or four months, this VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) the matter of three LUDWIG symphony, No. 4 in B-flat. Beethoven re ceived 500 gulden and, in turn, dedicated the hile working on his Sec work to Oppersdorff. ond Symphony, Beetho Oppersdorff was also involved in dis ven received an unex cussions about the Fifth Symphony, and it is pected commission from possible that this work, too, was at one stage the Court Theatre to com intended for the Count. -

The Commissioned Works of the National Flute Association For

THE COMMISSIONED WORKS OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION FOR THE YOUNG ARTIST AND HIGH SCHOOL SOLOIST COMPETITIONS DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kimberlee Goodman, M.M. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Document Committee: Approved by Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Adviser Dr. Robert Ward _____________________________ Dr. Susan Powell Adviser Music Graduate Program ABSTRACT The National Flute Association, an organization of professionals, amateurs, teachers, performers, and students has been active in the commissioning of new music for some of its competitions since 1986. The organization is responsible for more than forty new works for the Young Artist and High School Soloist competitions alone. The commissioning process has changed vastly over the years that the organization has been in existence. The National Flute Association commissions composers from all over the world to write pieces for two of its competitions; the Young Artist Competition has been commissioning works since 1986, and the High School Soloist Competition began commissioning new works in 1989. Additionally, the importance of the National Flute Association has led to many world premiere performances and individuals commissioning works to be premiered at the annual conventions. The purpose of this document is to highlight the competition commissioned works of this organization and its continuing commitment to presenting and championing new music. The National Flute Association has established itself as a leading organization in creating new works, and these commissioned pieces now represent a major body of work and a substantial portion of the newly composed repertoire for flute. -

CHAN 0607 QUANTZ.Qxd 9/1/08 12:39 Pm Page 1

CHAN 0607 QUANTZ.qxd 9/1/08 12:39 pm Page 1 Chan 0607 CHACONNE Quantz Flute Sonatas Premier recordings RACHEL BROWN James Johnstone harpsichord CHANDOS early music Mark Caudle cello CHAN 0607 BOOK.qxd 9/1/08 12:41 pm Page 2 Johann Joachim Quantz (1697–1773) Sonata No. 275 for flute and continuo 10:38 in B flat major . B-Dur . si bémol majeur 1 I Allegro di molto 2:58 2 II Affettuoso – 4:27 3 III Vivace 3:11 AKG Sonata for flute and obbligato harpsichord 7:43 in E flat major . Es-Dur . mi bémol majeur 4 I Allegro 2:51 5 II Larghetto – 2:11 6 III Vivace 2:38 Sonata XIV for flute and continuo 10:14 in G minor . g-Moll . sol mineur 7 I Grave – 3:50 8 II Allegro 2:48 9 III Lento – 1:05 10 IV Tempo di menuetto 2:29 Sonata No. 348 for flute and continuo 8:35 in E flat major . Es-Dur . mi bémol majeur Johann Joachim Quantz 11 I Arioso – 2:52 12 II Allegro assai 3:14 13 III Presto 2:26 Sonata No. 231 for flute and continuo 10:15 in B minor . h-Moll . si mineur 14 I Larghetto – 3:35 15 II Allegretto 3:33 16 III Presto 3:04 2 3 CHAN 0607 BOOK.qxd 9/1/08 12:41 pm Page 4 Sonata for flute and obbligato harpsichord 8:51 in E minor . e-Moll . mi mineur Quantz: Flute Sonatas 17 I Adagio – 2:10 18 II Allegro – 2:01 19 III Grazioso – 2:02 In former times composition was not so little from orphaned blacksmith’s son to his 20 IV Vivace 2:38 esteemed as at present, but there were then position as probably one of the best-paid fewer bunglers encountered than nowadays… musicians of his day as flute teacher and 21 Minuetto for flute d’amour and continuo 2:11 Today almost anyone who knows how to play director of private chamber music to an instrument passably pretends at the same Frederick the Great.