Antonio Vivaldi Concerti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamicsanddissonance: Theimpliedharmonictheoryof

Intégral 30 (2016) pp. 67–80 Dynamics and Dissonance: The Implied Harmonic Theory of J. J. Quantz by Evan Jones Abstract. Chapter 17, Section 6 of Quantz’s Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traver- siere zu spielen (1752) includes a short original composition entitled “Affettuoso di molto.” This piece features an unprecedented variety of dynamic markings, alternat- ing abruptly from loud to soft extremes and utilizing every intermediate gradation. Quantz’s discussion of this example provides an analytic context for the dynamic markings in the score: specific levels of relative amplitude are prescribed for particu- lar classes of harmonic events, depending on their relative dissonance. Quantz’s cat- egories anticipate Kirnberger’s distinction between essential and nonessential dis- sonance and closely coincide with even later conceptions as indicated by the various chords’ spans on the Oettingen–Riemann Tonnetz and on David Temperley’s “line of fifths.” The discovery of a striking degree of agreement between Quantz’s prescrip- tions for performance and more recent theoretical models offers a valuable perspec- tive on eighteenth-century musical intuitions and suggests that today’s intuitions might not be very different. Keywords and phrases: Quantz, Versuch, Affettuoso di molto, thoroughbass, disso- nance, dynamics, Kirnberger, Temperley, line of fifths, Tonnetz. 1. Dynamic Markings in Quantz’s ing. Like similarly conceived publications by C. P. E. Bach, “Affettuoso di molto” Leopold Mozart, and others, however, Quantz’s treatise en- gages -

A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 4-2018 State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First- Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy Tamara Tanner University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Tanner, Tamara, "State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 115. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY by Tamara J. Tanner A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Flute Performance Under the Supervision of Professor John R. Bailey Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2018 STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY Tamara J. Tanner, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2018 Advisor: John R. Bailey During the Baroque flute revival in 1970s Europe, American modern flute instructors who were interested in studying Baroque flute traveled to Europe to work with professional instructors. -

An Historical and Analytical Study of Renaissance Music for the Recorder and Its Influence on the Later Repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Woodhill, Vanessa, An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire, Master of Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2179 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] AN HISTORICAL AND ANALYTICAL STUDY OF RENAISSANCE MUSIC FOR THE RECORDER AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE LATER REPERTOIRE by VANESSA WOODHILL. B.Sc. L.T.C.L (Teachers). F.T.C.L A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Creative Arts in the University of Wollongong. "u»«viRsmr •*"! This thesis is submitted in accordance with the regulations of the University of Wotlongong in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis is the result of original research and has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other University or similar institution. Copyright for the extracts of musical works contained in this thesis subsists with a variety of publishers and individuals. Further copying or publishing of this thesis may require the permission of copyright owners. Signed SUMMARY The material in this thesis approaches Renaissance music in relation to the recorder player in three ways. -

Johann Joachim Quantz

Johann Joachim Quantz Portrait by an unknown 18th-century artist An account of his life taken largely from his autobiography published in 1754–5 Greg Dikmans Johann Joachim Quantz (1697–1773) Quantz was a flute player and composer at royal courts, writer on music and flute maker, and one of the most famous musicians of his day. His autobiography, published in F.W. Marpurg’s Historisch-kritische Beyträge (1754– 5), is the principal source of information on his life. It briefly describes his early years and then focuses on his activities in Dresden (1716–41), his Grand Tour (1724– 27) and his work at the court of Frederick the Great in Berlin and Potsdam (from 1741). Quantz was born in the village Oberscheden in the province of Hannover (northwestern Germany) on 30 January 1697. His father was a blacksmith. At the age of 11, after being orphaned, he began an apprenticeship (1708–13) with his uncle Justus Quantz, a town musician in Merseburg. Quantz writes: I wanted to be nothing but a musician. In August … I went to Merseburg to begin my apprenticeship with the former town-musician, Justus Quantz. … The first instrument which I had to learn was the violin, for which I also seemed to have the greatest liking and ability. Thereon followed the oboe and the trumpet. During my years as an apprentice I worked hardest on these three instruments. Merseburg Matthäus Merian While still an apprentice Quantz also arranged to have keyboard lessons: (1593–1650) Due to my own choosing, I took some lessons at this time on the clavier, which I was not required to learn, from a relative of mine, the organist Kiesewetter. -

MUSIC for a PRUSSIAN KING Friday 23 September 6Pm, Salon Presented by Melbourne Recital Centre and Accademia Arcadia

Accademia Arcadia MUSIC FOR A PRUSSIAN KING Friday 23 September 6pm, Salon Presented by Melbourne Recital Centre and Accademia Arcadia ARTISTS Greg Dikmans, Quantz flute Lucinda Moon, baroque violin Josephine Vains, baroque cello Jacqueline Ogeil, Christofori pianoforte PROGRAM FREDERICK II (THE GREAT) (1712–1786) Sonata in E minor for flute and cembalo Grave – Allegro assai – Presto JOHANN JOACHIM QUANTZ (1697–1773) Sonata in E minor for flute, violin and cembalo, QV 2:21 Adagio – Allegro – Gratioso – Vivace FRANZ BENDA (1709–1786) Sonata per il Violino Solo et Cembalo col Violoncello in G Adagio – Allegretto – Presto CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH (1714–1788) Sonata in A minor for flute, violin and bass, Wq 148 Allegretto – Adagio – Allegro assai ABOUT THE MUSIC No other statesman of his time did so much to promote music at court than Frederick the Great. During his years in Ruppin and Rheinsberg as Crown Prince, Frederick had already assembled a small chamber orchestra. The cultural life at the Prussian court was to receive an entirely new significance after Frederick’s accession to the throne in Berlin in 1740. Within a short time, Berlin’s musical life began to flower thanks to the young king’s decision to construct an opera house and to engage outstanding instrumentalists, singers and conductors. As a compensation for the demanding affairs of state, the Prussian king enjoyed playing and composing for the flute in a style closely following that of histeacher Johann Joachim Quantz. Quantz called this the mixed style, one that combined the German style with the bestelements of the Italian and French national styles. -

The Eminent Pedagogue Johann Joachim Quantz As Instructor Of

Kulturgeschichte Preuûens - Colloquien 6 (2018) Walter Kurt Kreyszig The Eminent Pedagogue Johann Joachim Quantz as Instructor of Frederick the Great During the Years 1728-1741: The Solfeggi, the Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversière zu spielen, and the Capricen, Fantasien und Anfangsstücke of Quantz, the Flötenbuch of Frederick the Great and Quantz, and the Achtundzwanzig Variationen über die Arie "Ich schlief, da träumte mir" of Quantz (QV 1:98) Abstract Johann Joachim Quantz (1697-1773), the flute instructor of Frederick the Great (1712-1786), played a seminal role in the development of the Prussian Court Music, during its formative years between 1713 and 1806. As a result of his lifetime appointment to the Court of Potsdam in 1741 by King Frederick the Great, Quantz was involved in numerous facets of the cultural endeavors at the Court, including his contributions to composition, performance and organology. Nowhere was his presence more acutely felt than in his formulation of music-pedagogical materials an activity where his knowledge as a preminent pedagogue and his skills as a composer, organologist and performer fused together in most astounding fashion. Quantz's effectiveness in his teaching of his most eminent student, Frederick the Great, is fully borne out in a number of documents, including the Solfeggi, the Versuch, the Caprices, Fantasien und Anfangsstücke, and the Achtundzwanzig Variationen über die Arie "Ich schlief, da träumte mir". While each document touches on different aspects of the musical discipline, these sources vividly underscore the intersection between musica theorica and musica practica and as such provide testimony of Johann Joachim Quantz as a genuine musicus. -

EC-Bach Perfection Programme-Draft.Indd

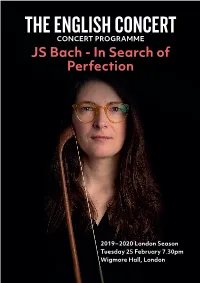

THE ENGLISH CONCE∏T 1 CONCERT PROGRAMME JS Bach - In Search of Perfection 2019 – 2020 London Season Tuesday 25 February 7.30pm Wigmore Hall, London 2 3 WELCOME PROGRAMME Wigmore Hall, More than any composer in history, Bach The English Concert 36 Wigmore Street, Orchestral Suite No 4 in D Johann Sebastian Bach is renowned Laurence Cummings London, W1U 2BP BWV 1069 Director: John Gilhooly for having frequently returned to his Guest Director / The Wigmore Hall Trust own music. Repurposing and revising it Bach Harpsichord Registered Charity for new performance contexts, he was Sinfonia to Cantata 35: No. 1024838. Lisa Beznosiuk Geist und Seele wird verwirret www.wigmore-hall.org.uk apparently unable to help himself from Flute Disabled Access making changes and refinements at Bach and Facilities Tabea Debus Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D every level. Recorder BWV 1050 Tom Foster In this programme, we explore six of Wigmore Hall is a no-smoking INTERVAL Organ venue. No recording or photographic Bach’s most fascinating works — some equipment may be taken into the Sarah Humphrys auditorium, nor used in any other part well known, others hardly known at of the Hall without the prior written Bach Recorder permission of the Hall Management. all. Each has its own story to tell, in Sinfonia to Cantata 169: Wigmore Hall is equipped with a Tuomo Suni ‘Loop’ to help hearing aid users receive illuminating Bach’s working processes Gott soll allein mein Herze haben clear sound without background Violin and revealing how he relentlessly noise. Patrons can use the facility by Bach switching their hearing aids over to ‘T’. -

1) Musikstunde

__________________________________________________________________________ 2 SWR 2 Musikstunde Dienstag, den 10. Januar 2012 Mit Susanne Herzog Il prete rosso Vivaldi, der Lehrer Kulturinteressierte Venedigreisende haben heutzutage ihren Dumont im Gepäck: damit etwa keine Fragen offen bleiben, wenn man sich angestrengt den Kopf verrenkt, um die Tintoretto Deckengemälde in der Scuola di San Rocco zu bewundern oder um die Details von Tizians Assunta in der Frarikirche zu verstehen. Schon zu Vivaldis Zeiten kamen unglaubliche Mengen an Besuchern nach Venedig: in Stosszeiten soviel wie die Hälfte der Bevölkerung der schwimmenden Stadt. Allerdings nicht nur der kunsthistorischen Schätze wegen, sondern durchaus auch um die Musik Venedigs zu genießen. Und diesbezüglich sprach Vincenzo Coronelli in seinem Reiseführer für Venedig in der Ausgabe von 1706 eine ganz klare Empfehlung aus: „Unter den besseren Geigern sind einzigartig Giovanni Battista Vivaldi und sein Sohn, der Priester.“ Vater und Sohn Vivaldi also galten als Geigenstars. Kaum anders ist es auch zu verstehen, dass Vivaldi mit nur fünfundzwanzig Jahren im Ospedale della Pietà Maestro di Violino wurde. Nicht nur die dortigen Mädchen allerdings kamen in den Genuss seines Unterrichts, sondern schon etablierte Geiger wie etwa der spätere Dresdner Konzertmeister Johann Georg Pisendel nahmen private Geigenstunden bei Vivaldi, um sich zu vervollkommnen. Vivaldi als Lehrer: das ist heute das Thema der SWR 2 Musikstunde. Und dass man nicht nur von einem real anwesenden Lehrer etwas lernen kann, sondern dass auch Noten selbst sprechen, dazu am Ende dieser Stunde noch mehr. 1’25 2 3 Musik 1 Antonio Vivaldi Erster Satz aus Concerto B-dur, RV 368 <16> 3’45 Anton Steck, Violine Modo Antiquo Federico Maria Sardelli Titel CD: Concerti per violino II ‘Di sfida’ Naïve, OP 30427, LC 5718 Privat CD Anton Steck, einer der großen Barockgeiger unserer Zeit hat über dieses Konzert Vivaldis gesagt, da gäbe es Passagen, die würde man eigentlich eher bei Paganini erwarten. -

"Mixed Taste," Cosmopolitanism, and Intertextuality in Georg Philipp

“MIXED TASTE,” COSMOPOLITANISM, AND INTERTEXTUALITY IN GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN’S OPERA ORPHEUS Robert A. Rue A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2017 Committee: Arne Spohr, Advisor Mary Natvig Gregory Decker © 2017 Robert A. Rue All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Arne Spohr, Advisor Musicologists have been debating the concept of European national music styles in the Baroque period for nearly 300 years. But what precisely constitutes these so-called French, Italian, and German “tastes”? Furthermore, how do contemporary sources confront this issue and how do they delineate these musical constructs? In his Music for a Mixed Taste (2008), Steven Zohn achieves success in identifying musical tastes in some of Georg Phillip Telemann’s instrumental music. However, instrumental music comprises only a portion of Telemann’s musical output. My thesis follows Zohn’s work by identifying these same national styles in opera: namely, Telemann’s Orpheus (Hamburg, 1726), in which the composer sets French, Italian, and German texts to music. I argue that though identifying the interrelation between elements of musical style and the use of specific languages, we will have a better understanding of what Telemann and his contemporaries thought of as national tastes. I will begin my examination by identifying some of the issues surrounding a selection of contemporary treatises, in order explicate the problems and benefits of their use. These sources include Johann Joachim Quantz’s Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte zu spielen (1752), two of Telemann’s autobiographies (1718 and 1740), and Johann Adolf Scheibe’s Critischer Musikus (1737). -

A Técnica De Arranjo E Transcrição De Johann Sebastian Bach T ______E Pedro Rodrigues Universidade De Aveiro S

D E B A A técnica de arranjo e transcrição de Johann Sebastian Bach T _________________________________________________ E Pedro Rodrigues Universidade de Aveiro S Resumo: a utilização de música não originalmente escrita para violão assume, actualmente, um papel fundamental para a multiplicidade de concepções de repertórios. O presente trabalho apresenta um levantamento de processos transcricionais usados por 14 Johann Sebastian Bach em suas transcrições e arranjos. Este conjunto de técnicas permite encontrar alternativas às eventuais problemáticas levantadas durante a transcrição e simultaneamente, processos para manter inalterada a significação proposta pelo compositor. A análise apresentada deverá possibilitar a transcrição de obras onde a facies, diferente do texto original, não comprometerá a significatio proposta pelo seu compositor e, graças à análise histórica, emergir no futuro com novas criações. A constatação de elementos diferenciadores (ad exemplum timbre, cor, elaboração, redução, transposição) reforça a comparação de contrastes entre obra original e obra transcrita. Adicionalmente, este trabalho deseja reforçar a independência estética que se associa a cada uma das versões. Pretende-se assim uma maior conscientização do processo que poderemos chamar de transcricional para que o repertório violonístico alcance uma maior amplitude. Palavras-chave: Transcrição. Arranjo. Violão. Barroco. Performance Johann Sebastian Bach’s method of arrangement and transcription Abstract: The use of music no originally written for guitar, has, nowadays, a main role in the construction of multiple repertories. This work presents an analysis of transcriptional processes used by Johann Sebastian Bach in his arrangements and transcriptions. The array of processes provides alternatives to eventual problems raised during the transcription elaboration and at the same time, options to maintain unaltered the musical intention proposed by the composer. -

18-08-01 EVE Zimmermann's Coffeehouse.Indd

VANCOUVER BACH FESTIVAL 2018 wednesday august 1 at 7:30 pm | christ church cathedral the artists zimmermann’s coffee house and garden Soile Stratkauskas George Frideric Handel (1685–1759): flute Trio Sonata Op. 2 no. 1 hwv 386b Beiliang Zhu Andante Allegro ma non troppo cello Largo Chloe Meyers Allegro violin Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–1788): Alexander Weimann 12 Variations on “La Folia d’Espagne” Wq 118:9 harpsichord George Frideric Handel: Sonata Op. 1 no. 7 hwv 365 Larghetto Allegro Double-manual harpsichord Larghetto from the collection of Early Music A tempo di Gavotti Vancouver, built in the mid-70s by Allegro Edward R. Turner of Pender Island after a superb eighteenth-century Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750): instrument by Pascal Taskin, now Violin sonata in E minor bwv 1023 housed in the Russell Collection in Edinburgh. — Adagio ma non tanto Allemande Supported by the Gigue interval Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767): Sonata in G for Flute and Violin (from Der getreue Music-Meister) twv 40:111 Dolce Coffee generously provided by Scherzando Largo e misurato Vivace e staccato Nicola Antonio Porpora (1686-1768): Cello Sonata in F major Pre-concert chat with Largo host Matthew White at 6:45: Allegro Alexander Weimann Adagio Allegro ma non presto Georg Philipp Telemann: Paris Quartet (“Concerto”) in D major twv 43:D1 THE UNAUTHORISED USE OF Allegro ANY VIDEO OR AUDIO RECORDING Affetuoso DEVICE IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED Vivace earlymusic.bc.ca Zimmermann’s Coffee House and Garden Vancouver Bach Festival 2018 1 programme notes by christina hutten Just off the market square, on the most elegant street in Leipzig, a musical master passed through [Leipzig] without getting to step with me under the coloured awnings and through the door know my father and playing for him.” into Herr Zimmermann’s café. -

Bach: a Beautiful Mind Sat 18 Jan, Milton Court Concert Hall 2 Bach: a Beautiful Mind Sat 18 Jan, Milton Court Concert Hall Important Information Allowed in the Hall

Sat 18 Jan, Milton Court Milton Concert Jan, Hall Sat 18 Bach: A Beautiful Mind Sat 18 & Sun 19 Jan Milton Court Concert Hall Part of Barbican Presents 2019–20 Bach: A Beautiful Mind Kaja Smith Kaja 1 Important information Sat 18 Jan, Milton Court Milton Concert Jan, Hall Sat 18 When do the events I’m running late! Please… start? Latecomers will be Switch any watch There are talks at admitted if there is a alarms and mobile 1.30pm and 5pm; the suitable break in the phones to silent during concerts are at 2.30pm performance. the performance. and 7.30pm. Please don’t… Use a hearing aid? Need a break? Take photos or Please use our induction You can leave at any recordings during the loop – just switch your time and be readmitted if performance – save it hearing aid to T setting there is a suitable break for the curtain call. on entering the hall. in the performance, or during the interval. Looking for Looking for Carrying bags refreshment? the toilets? and coats? Bars are located on The nearest toilets, Drop them off at our free Levels 1 and 2. Pre-order including accessible cloak room on Level -1. interval drinks to beat the toilets, are located on the queues. Drinks are not Ground Floor and Level Bach: A Beautiful Mind allowed in the hall. 2. There are accessible toilets on every level. 2 Welcome to today’s performances Bach: A Beautiful Mind is part of Today is the first instalment of our Bach Inside Out, a year exploring the celebration, which has been curated by relationship between our inner lives superstar harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani.