A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2016 The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument Victoria A. Hargrove Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hargrove, Victoria A., "The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 236. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT Victoria A. Hargrove COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO HONORS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE HONORS IN THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHWOB SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE OF THE ARTS BY VICTORIA A. HARGROVE THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT By Victoria A. Hargrove A Thesis Submitted to the HONORS COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Degree of BACHELOR OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS Thesis Advisor Date ^ It, Committee Member U/oCWV arcJc\jL uu? t Date Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz A Honors College Dean ABSTRACT The purpose of this lecture recital was to reflect upon the rapid mechanical progression of the clarinet, a fairly new instrument to the musical world and how these quick changes effected the way composers were writing music for the instrument. -

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer

m^^^^j^^fjSjmggU ^^If0jisdii^ Accompanist to Boston Symphony Orchestra Berkshire Festival • Berkshire Music Center and to these Tanglewood 1971 artists Leonard Bernstein • Arthur Fiedler • Byron Janis • Ruth Laredo Seiji Ozawa • Gunther SchuIIer • Michael Tilson Thomas • Earl Wild BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WILLIAM STEINBERG Music Director MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Associate Conductor NINETIETH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 1970-1971 TANGLEWOOD 1971 SEIJI OZAWA, GUNTHER SCHULLER Artistic Directors LEONARD BERNSTEIN Advisor THIRTY-FOURTH BERKSHIRE FESTIVAL THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President ABRAM T. COLLIER HENRY A. LAUGHLIN PHILIP K. ALLEN Vice-President MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK EDWARD G. MURRAY ROBERT H. GARDINER Vice-President THEODORE P. FERRIS JOHN T. NOONAN JOHN L. THORNDIKE Treasurer FRANCIS W. HATCH MRS JAMES H. PERKINS ALLEN G. BARRY HAROLD D. HODGKINSON IRVING W. RABB RICHARD P. CHAPMAN E. MORTON JENNINGS JR SIDNEY STONEMAN EDWARD M. KENNEDY TRUSTEES EMERITUS HENRY B. CABOT PALFREY PERKINS EDWARD A. TAFT THE BOARD OF OVERSEERS OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. ERWIN D. CANHAM Chairman HENRY B. DEWEY LAWRENCE K. MILLER VERNON ALDEN Vice-Chairman RICHARD A. EHRLICH FRANK E. MORRIS LEONARD KAPLAN Secretary/ BYRON K. ELLIOTT MRS STEPHEN V. C. MORRIS HAZEN H. AYER ARCHIE C. EPPS III JOHN T. G. NICHOLS MRS FRANK G. ALLEN PAUL FROMM LOUVILLE NILES ROBERT C. ALSOP CARLTON P. FULLER DAVID R. POKROSS LEO L. BERANEK MRS ALBERT GOODHUE MRS BROOKS POTTER DAVID W. BERNSTEIN MRS JOHN L. GRANDIN HERBERT W. PRATT MRS CURTIS B. BROOKS STEPHEN W. GRANT MRS FAIRFIELD E. RAYMOND J. CARTER BROWN SAMUEL A. GROVES PAUL C. REARDON MRS LOUIS W. -

Eubo Mobile Baroque Academy

EUBO MOBILE BAROQUE ACADEMY EUROPEAN CO OPERATION PROJECT 2015 2018 INTERIM REPORT Pathways & Performances CONTENTS EUBO MOBILE BAROQUE ACADEMY........................................2?3 PARTNER ORGANISATIONS ....................................................4?13 INTERNATIONAL CONCERT TOURS ....................................14?18 MUSIC EDUCATION ...............................................................19?22 OTHER ACTIVITIES ................................................................23?25 HOW DO WE MAKE ALL THIS HAPPEN ................................26?27 WHO IS WHO................................................................................28 EUBO MOBILE BAROQUE ACADEMY The EUBO Mobile Baroque Academy (EMBA) co-operation project addresses the unequal provision across the European Union of baroque music education and performance, in new and creative ways. The EMBA project builds on the 30-year successful track-record of the European Union Baroque Orchestra (EUBO) in providing training and performing opportunities for young EU period performance musicians and extends and develops possibilities for orchestral musicians intending to pursue a professional career. From an earlier stage of conservatoire training via orchestral experience, through to the first steps in the professional world, musicians attending the activities of EMBA are offered a pathway into the profession. The EMBA activities supporting the development of emerging musicians include specialist masterclasses by expert tutors; residential orchestral selection -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1961-1962

Music Shed — Tanglewood Lenox, Massachusetts Thursday, August 2, 1962, at 8:00 For the Benefit of the Berkshire Music Center THE BOSTON POPS ARTHUR FIEDLER, Conductor Soloist EARL WILD, Piano PROGRAM *The Stars and Stripes Forever Sousa *Suite from "Le Cid" Massenet Castiliane — Aragonaise — Aubade — Navarraise #Mein Lebenslauf ist Lieb' und Lust, Waltzes Josef Strauss Pines of Rome Respighi I. The Pines of the Villa Borghese II. The Pines near a Catacomb III. The Pines of the Janiculum IV. The Pines of the Appian Way Intermission *Concerto in F for Piano and Orchestra Gershwin I. Allegro II. Adagio; Andante con moto III. Allegro agitato Soloist: Earl Wild *Selection from "West Side Story" Bernstein I Feel Pretty — Maria — Something's Coming — Tonight — One Hand, One Heart — Cool — A-mer-i-ca Mr. Wild plays the Baldwin Piano Baldwin Piano *RCA Victor Recording Special Event at Tanglewood Thursday, August 23 A GALA EVENING of Performances by the Students For the Benefit of the Berkshire Music Center ORDER OF EVENTS 4 :00 Chamber Music in the Theatre 5 :00 Music by Tanglewood Composers in the Chamber Music Hall 6:00 Picnic Hour 7 :00 Tanglewood Choir on the Main House Porch 8 :00 The Berkshire Music Center Orchestra Concert in the Shed In Mahler's Third Symphony, with the Festival Chorus and Florence Kopleff, Contralto Conductor—Richard Burgin Admission tickets . (All seats unreserved except boxes) $2.50 — Box Seats $5.00 Grounds open for admission at 3 :00 p.m. REMAINING FESTIVAL CONCERTS (The final concerts of Charles Munch as Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra) EVENINGS — 8 :00 P.M. -

2006 Heft 1 Zum Heft

MAGAZIN FÜR HOLZBLÄSER Eine Vierteljahresschrift · Einzelheft € 6,50 Heft 1/2006 Heft SSppiieellrrääuummee –– MOECK Seminare Termin: jeweils Samstags von 10.00 – 17.00 Uhr 2006 Ort: Kreismusikschule Celle, Kanonenstr. 4, 29221 Celle Carin van Heerden Peter Holtslag Der singende Telemann Der „gute“ Klang und die Blockflöte Seminar 1: 18. Februar 2006 – Widerspruch, Utopie oder Realität? Seminar 2: 6. Mai 2006 Werke von Georg Philipp Telemann für und mit Was macht einen guten Blockflötenklang aus und Blockflöte werden in diesem Workshop in Einzel- wie entsteht er? Welche Rolle spielt mein Körper? und Kammermusikstunden erarbeitet. Telemanns Muss man jeden Tag einen Marathon laufen und 2 Leitsatz Singen ist das Fundament zur Music in Liter Vitaminsaft trinken, um körperlich fit zu sein allen Dingen … Wer die Composition ergreifft, für den guten Klang? Reicht es schon aus, ein muß in seinen Sätzen singen soll die gemeinsame Instru ment der Spitzenklasse zu kaufen? Welche Arbeit an seinen Solo- und Kammermusikwerken Rol le spielen Vorstellungsvermögen und Suggesti- prägen. Eingeladen sind alle Block flötistInnen die vität? Welcher Klang passt zu welcher Musik? Wel- das Melodische bei Telemann lieben. che aufführungspraktischen Tendenzen spielen Ein Cembalo in 440 und 415 Hz sowie ein Beglei- eine Rolle für den Klang? Und: was bedeutet ter stehen bei Bedarf zur Verfügung. eigentlich „guter“ Geschmack und „guter“ Klang? In der ersten Stunde findet eine Einführung ins Folgende Werke können u. a. erarbeitet werden: Thema statt, veranschaulicht mit Klangbeispielen. – 6 Partitas (Die kleine Kammermusik für Block - Dann folgen gemeinsame Übungen und das Erar- flöte und B.c.) beiten von Stücken. – 12 Fantasien für Blockflöte solo Literaturvorschläge: – Sonaten für Altblockflöte und B.c. -

The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1966 The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions J. Wayne Johnson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, J. Wayne, "The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions" (1966). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2804. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2804 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IDENTIFICATION OF BAS~C PROBLEMS FOUND IN THE BASSOON PARTS OF A SELECTED GROUP OF BAND COMPOSITI ONS by J. Wayne Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the r equ irements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Music Education UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan , Ut a h 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BASSOON 3 THE I NSTRUMENT 20 Testing the bassoon 20 Removing moisture 22 Oiling 23 Suspending the bassoon 24 The reed 24 Adjusting the reed 25 Testing the r eed 28 Care of the reed 29 TONAL PROBLEMS FOUND IN BAND MUSIC 31 Range and embouchure ad j ustment 31 Embouchure · 35 Intonation 37 Breath control 38 Tonguing 40 KEY SIGNATURES AND RELATED FINGERINGS 43 INTERPRETIVE ASPECTS 50 Terms and symbols Rhythm patterns SUMMARY 55 LITERATURE CITED 56 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. -

Music in the Pavilion

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA LIBRARIES KISLAK CENTER Music in the Pavilion PHOTO BY SHARON TERELLO NIGHT MUSIC A SUBTLE AROMA OF ROMANTICISM Friday, September 27, 2019 Class of 1978 Orrery Pavilion Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center www.library.upenn.edu/about/exhibits-events/music-pavilion .................................................................................. .................................................................................. .................................................................................. .................................................................................................................................................................... .................................................................................. ........... ............ ......... A SUBTLE AROMA OF ROMANTICISM NIGHT MUSIC Andrew Willis, piano Steven Zohn, flute Rebecca Harris, violin Amy Leonard, viola Eve Miller, cello Heather Miller Lardin, double bass PIANO TRIO IN D MINOR, OP. 49 (1840) FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–47) MOLTO ALLEGRO AGITATO ANDANTE CON MOTO TRANQUILLO SCHERZO: LEGGIERO E VIVACE FINALE: ALLEGRO ASSAI APPASSIONATO PIANO QUINTET IN A MINOR, OP. 30 (1842) LOUISE FARRENC (1804–75) ALLEGRO ADAGIO NON TROPPO SCHERZO: PRESTO FINALE: ALLEGRO The piano used for this concert was built in 1846 by the Paris firm of Sébastien Érard. It is a generous gift to the Music Department by Mr. Yves Gaden (G ’73), in loving memory of his wife Monique (1950-2009). ................................................................................... -

Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection

Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division at the Library of Congress Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 2004 Table of Contents Introduction...........................................................................................................................................................iii Biographical Sketch...............................................................................................................................................vi Scope and Content Note......................................................................................................................................viii Description of Series..............................................................................................................................................xi Container List..........................................................................................................................................................1 FLUTES OF DAYTON C. MILLER................................................................................................................1 ii Introduction Thomas Jefferson's library is the foundation of the collections of the Library of Congress. Congress purchased it to replace the books that had been destroyed in 1814, when the Capitol was burned during the War of 1812. Reflecting Jefferson's universal interests and knowledge, the acquisition established the broad scope of the Library's future collections, which, over the years, were enriched by copyright -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo. -

N Ew Y O R K F Lu T E F a Ir 2021

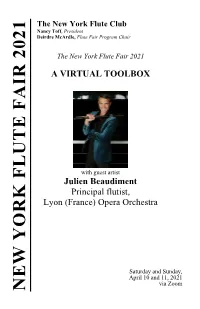

The New York Flute Club Nancy Toff, President Deirdre McArdle, Flute Fair Program Chair The New York Flute Fair 2021 A VIRTUAL TOOLBOX with guest artist Julien Beaudiment Principal flutist, Lyon (France) Opera Orchestra Saturday and Sunday, April 10 and 11, 2021 via Zoom NEW YORK FLUTE FAIR 2021 BOARD OF DIRECTORS NANCY TOFF, President PATRICIA ZUBER, First Vice President KAORU HINATA, Second Vice President DEIRDRE MCARDLE, Recording Secretary KATHERINE SAENGER, Membership Secretary MAY YU WU, Treasurer AMY APPLETON JEFF MITCHELL JENNY CLINE NICOLE SCHROEDER RAIMATO DIANE COUZENS LINDA RAPPAPORT FRED MARCUSA JAYN ROSENFELD JUDITH MENDENHALL RIE SCHMIDT MALCOLM SPECTOR ADVISORY BOARD JEANNE BAXTRESSER ROBERT LANGEVIN STEFÁN RAGNAR HÖSKULDSSON MICHAEL PARLOFF SUE ANN KAHN RENÉE SIEBERT PAST PRESIDENTS Georges Barrère, 1920-1944 Eleanor Lawrence, 1979-1982 John Wummer, 1944-1947 John Solum, 1983-1986 Milton Wittgenstein, 1947-1952 Eleanor Lawrence, 1986-1989 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1952-1955 Sue Ann Kahn, 1989-1992 Frederick Wilkins, 1955-1957 Nancy Toff, 1992-1995 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1957-1960 Rie Schmidt, 1995-1998 Paige Brook, 1960-1963 Patricia Spencer, 1998-2001 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1963-1964 Jan Vinci, 2001-2002 Maurice S. Rosen, 1964-1967 Jayn Rosenfeld, 2002-2005 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1967-1970 David Wechsler, 2005-2008 Paige Brook, 1970-1973 Nancy Toff, 2008-2011 Eleanor Lawrence, 1973-1976 John McMurtery, 2011-2012 Harold Jones, 1976-1979 Wendy Stern, 2012-2015 Patricia Zuber, 2015-2018 FLUTE FAIR STAFF Program Chair: Deirdre McArdle -

Nov 23 to 29.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Nov. 23 - Nov. 29, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 11/23/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto for Viola d'amore, lute & orch. 6:15 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 6:29 AM Georg Muffat Sonata No.1 6:42 AM Marianne Martinez Sinfonia 7:02 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for 2 violas 7:09 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Eleven Dances 7:29 AM Henry Purcell Chacony a 4 7:37 AM Robert Schumann Waldszenen 8:02 AM Johann David Heinichen Concerto for 2 flutes, oboes, vn, string 8:15 AM Antonin Reicha Commemoration Symphony 8:36 AM Ernst von Dohnányi Serenade for Strings 9:05 AM Hector Berlioz Harold in Italy 9:46 AM Franz Schubert Moments Musicaux No. 6 9:53 AM Ernesto de Curtis Torna a Surriento 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Rondo for horn & orch 10:07 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento No. 3 10:21 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata 10:39 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Allegro for Clarinet & String Quartet 10:49 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento No. 8 11:01 AM Aaron Copland Appalachian Spring (Ballet for Martha) 11:29 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Violin Partita No. 2 12:01 PM Bedrich Smetana Ma Vlast: The Moldau ("Vltava") 12:16 PM Astor Piazzolla Tangazo 12:31 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Artist's Life 12:43 PM Luigi Boccherini Flute Quintet No. 3 12:53 PM John Williams (Comp./Cond.) Summon the Heroes 1:01 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Piano Trio No. 1 1:36 PM Margaret Griebling-Haigh Romans des Rois 2:00 PM Johann Sebastian Bach Konzertsatz (Sinfonia) for vln,3 trpts.