London Classical Players

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Academy Fee the Academy Fee Is 540 € for Each Participant

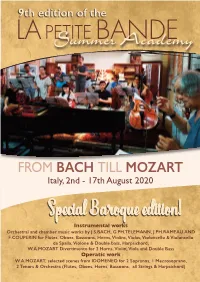

9th edition of the LA PESTuITmE mBerA ANcaDdEemy FROM BACH TILL MOZART Italy, 2nd - 17th August 2020 SpeciIanstlr uBmenatarl woorqks ue edition! Orchestral and chamber music works by J.S.BACH, G.PH.TELEMANN, J.PH.RAMEAU AND F.COUPERIN for Flutes, Oboes, Bassoons, Horns, Violins, Violas, Violoncello & Violoncello da Spalla, Violone & Double bass, Harpsichord; W.A.MOZART Divertimento for 2 Horns, Violin, Viola and Double Bass Operatic work W.A.MOZART, selected scenes from IDOMENEO for 2 Sopranos, 1 Mezzosoprano, 2 Tenors & Orchestra (Flutes, Oboes, Horns, Bassoons, all Strings & Harpsichord) LA PESTuITmE mBerA ANcaDdEemy Since 2012, La Petite BandeA orgpanpizleis caa yetairolyn Susm mforer A c2ad0em2y 0in Itaalyr, ew hnicho wwith othpe eyenar! s has become a beloved international appointment for many musicians desiring to deepen their knowledge and practice of historically informed practice for the baroque and classical repertoire (especially Mozart & Haydn). Indeed, they have taken their chance to work with one of the pioneers of this field, violinist and leader of La Petite Bande, Sigiswald Kuijken. Each year, the Academy focuses both on instrumental and operatic works. Singers work with Marie Kuijken on a historically informed approach to the textual and scenical aspects of the score, and perform the opera with the orchestra. The 2020 edition is a special BAROQUE edition, in which the instrumental focus will be on orchestral and chamber music works of J.S.Bach, G.Telemann, J.Ph.Rameau aBnda F.rCooupqeruine. By choosing mostly to play one-to-a-part, for these works the difference between orchestral and chambermusic playing will be minimal. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 4-2018 State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First- Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy Tamara Tanner University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Tanner, Tamara, "State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 115. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY by Tamara J. Tanner A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Flute Performance Under the Supervision of Professor John R. Bailey Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2018 STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY Tamara J. Tanner, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2018 Advisor: John R. Bailey During the Baroque flute revival in 1970s Europe, American modern flute instructors who were interested in studying Baroque flute traveled to Europe to work with professional instructors. -

La Petite Bande Olv

2007-2008 BLAUWE ZAAL DO 24 APRIL 2008 La Petite Bande olv. Sigiswald Kuijken 2007-2008 Bach wo 14 november 2007 KOOR & ORKEST COLLEGIUM VOCALE GENT OLV. PHILIppE HERREWEGHE za 15 december 2007 FREIBURGER BAROckORCHESTER & COLLEGIUM VOCALE GENT OLV. MASAAKI SUZUKI do 24 april 2008 LA PETITE BANDE OLV. SIGISWALD KUIJKEN Bach LA PETITE BANDE SIGISWALD KUIJKEN muzikale leiding SIRI THORNHILL sopraan PETRA NOskAIOVÁ mezzo CHRISTOPH GENZ tenor JAN VAN DER CRAbbEN bas JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) Cantate ‘Es ist euch gut, dass ich hingehe’, BWV108 20’ Pictogrammen DeSingel AUDIO gelieve uw GSM uit te schakelen Cantate ‘Wahrlich, wahrlich, ich sage euch’, BWV86 18’ Cantate ‘Sie werden euch in den Bann tun’, BWV44 22’ pauze De inleidingen kan u achteraf beluisteren via www.desingel.be Selecteer hiervoor voorstelling/concert/tentoonstelling van uw keuze. Himmelfahrtsoratorium REAGEER ‘Lobet Gott in seinen Reichen’, BWV11 32’ & WIN Op www.desingel.be kan u uw visie, opinie, commentaar, appreciatie, … betreffende het programma van deSingel met andere toeschouwers delen. Selecteer hiervoor voorstelling/ concert/tentoonstelling van uw keuze. Neemt u deel aan dit forum, dan maakt u meteen kans om tickets te winnen. Bij elk concert worden cd’s te koop aangeboden door ’t KLAverVIER, Kasteeldreef 6, Schilde, 03 384 29 70 > www.tklavervier.be foyer deSingel enkel open bij avondvoorstellingen in rode en/of blauwe zaal open vanaf 18.40 uur kleine koude of warme gerechten te bestellen vóór 19.20 uur broodjes tot net vóór aanvang van de voorstellingen -

Andrè Schuen’S Repertory Ranges from Early Music to Contemporary Music, and He Is Equally Comfortable in the Genres of Oratorio, Lied and Opera

A NDRÈ S CHUEN - Baritone Born in 1984, he studied at the Mozarteum of Salzburg with Gudrun Volkert, Horiana Branisteanu, Josef Wallnig and Hermann Keckeis (opera), and with Wolfgang Holzmair (Lied and oratorio). He has appeared as soloist of Salzburg Concert Association, Collegium Musicum Salzburg, Salzburg Bach Society, and has already sung with such renowned orchestras as Wiener Philharmoniker, Mozarteum Orchestra and Camerata Salzburg, with such conductor as Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Philippe Jordan, Simon Rattle, Ivor Bolton, Roger Norrington and Ingo Metzmacher. Andrè Schuen’s repertory ranges from early music to contemporary music, and he is equally comfortable in the genres of oratorio, lied and opera. Concerts, festivals and tv appearances have taken him to Vienna, Berlin, Munich, Dresden, Zurich, Tokyo, Puebla (Mexico), Buenos Aires and Ushuaia (Argentina). At the Salzburg Festival in 2006, he sang the bass choral solo in Mozart’s Idomeneo under Roger Norrington. During the 2007/08 season, he performed the role of Ein Lakai in Ariadne auf Naxos under Ivor Bolton in a new production of Salzburg State Theater at the Haus für Mozart. He also performed the role of Figaro in Le nozze di Figaro at Mozarteum in Salzburg and at various theaters in Germany and Austria. In August of 2009, he sang as Basso I in Luigi Nono’s Al gran sole carico d’amore at Salzburg Festival, conducted by Ingo Metzmacher. In August of 2009 he was awarded the “Walter-und- Charlotte-Hamel-Stiftung” and the “Internationale Sommerakademie Mozarteum Salzburg”. In the summer of 2010 he took part in the Young Singers Project at Salzburg Festival. -

Æ'xªêgš3{ Þi—ºes"Ƒ Wuãe"

557249bk Buxtehude US 7/10/05 5:16 pm Page 8 Dietrich Buxtehude (c.1637–1707): Complete Chamber Music • 2 Seven Trio Sonatas, Op. 2 BUXTEHUDE Sonata No. 1 in B flat major, 8:33 Sonata No. 5 in A major, 9:15 BuxWV 259 BuxWV 263 Seven Trio Sonatas, Op. 2 1 Allegro 1:23 ^ Allegro 1:01 2 Adagio – Allegro 2:23 & Violino solo – Concitato 3:19 John Holloway, Violin 3 Grave 1:34 * Adagio: Viola da gamba solo 1:21 4 Vivace – Lento 1:14 ( Allegro – Adagio 1:19 Jaap ter Linden, Viola da gamba 5 Poco adagio – Presto 1:59 ) 6/4 – Poco presto 2:14 Lars Ulrik Mortensen, Harpsichord Sonata No. 2 in D major, 9:06 Sonata No. 6 in E major, 8:37 BuxWV 260 BuxWV 264 6 Adagio – Allegro – Largo 3:13 ¡ Grave – Vivace 3:23 7 Ariette, Parte I–X 3:40 ™ Adagio – Poco presto – Lento 3:39 8 Largo – Vivace 2:14 £ Allegro 1:34 Sonata No. 3 in G minor, 10:54 Sonata No. 7 in F major, 8:15 BuxWV 261 BuxWV 265 9 Vivace – Lento 3:07 ¢ Adagio – 4/4 3:02 0 Allegro – Lento 1:25 ∞ Lento – Vivace 2:20 ! Andante 3:16 § Largo – Allegro 2:53 @ Grave – Gigue 3:06 This recording has been based on the following editions: Dieterich Buxtehude: VII. Suonate à doi, Sonata No. 4 in C minor, 8:32 Violino & Violadagamba, con Cembalo, Opus. 1, BuxWV 262 Hamburg [1694] – Opus 2, Hamburg 1696. Facsimile # Poco adagio 1:45 edition, vol. 1-2, with an introduction by Kerala J $ Allegro – Lento 2:03 Snyder. -

Prospectus 19/ 20 Trinity Laban Conservatoire Of

PROSPECTUS 19/20 TRINITY LABAN CONSERVATOIRE OF MUSIC & DANCE CONTENTS 3 Principal’s Welcome 56 Music 4 Why You Should #ChooseTL 58 Performance Opportunities 6 How to #ExperienceTL 60 Music Programmes FORWARD 8 Our Home in London 60 Undergraduate Programmes 10 Student Life 62 Postgraduate Programmes 64 Professional Development Programmes 12 Accommodation 13 Students' Union 66 Academic Studies 14 Student Services 70 Music Departments 16 International Community 70 Music Education THINKING 18 Global Links 72 Composition 74 Jazz Trinity Laban is a unique partnership 20 Professional Partnerships 76 Keyboard in music and dance that is redefining 22 CoLab 78 Strings the conservatoire of the 21st century. 24 Research 80 Vocal Studies 82 Wind, Brass & Percussion Our mission: to advance the art forms 28 Dance 86 Careers in Music of music and dance by bringing together 30 Dance Staff 88 Music Alumni artists to train, collaborate, research WELCOME 32 Performance Environment and perform in an environment of 98 Musical Theatre 34 Transitions Dance Company creative and technical excellence. 36 Dance Programmes 106 How to Apply 36 Undergraduate Programmes 108 Auditions 40 Masters Programmes 44 Diploma Programmes 110 Fees, Funding & Scholarships 46 Careers in Dance 111 Admissions FAQs 48 Dance Alumni 114 How to Find Us Trinity Laban, the UK’s first conservatoire of music and dance, was formed in 2005 by the coming together of Trinity College of Music and Laban, two leading centres of music and dance. Building on our distinctive heritage – and our extensive experience in providing innovative education and training in the performing arts – we embrace the new, the experimental and the unexpected. -

Handel's Messiah Freiburg Baroque Orchestra

Handel’s Messiah Freiburg Baroque Orchestra Wednesday 11 December 2019 7pm, Hall Handel Messiah Freiburg Baroque Orchestra Zürcher Sing-Akademie Trevor Pinnock director Katherine Watson soprano Claudia Huckle contralto James Way tenor Ashley Riches bass-baritone Matthias von der Tann Matthias von There will be one interval of 20 minutes between Part 1 and Part 2 Part of Barbican Presents 2019–20 Please do ... Turn off watch alarms and phones during the performance. Please don’t ... Take photos or make recordings during the performance. Use a hearing aid? Please use our induction loop – just switch your hearing aid to T setting on entering the hall. The City of London Corporation Programme produced by Harriet Smith; is the founder and advertising by Cabbell (tel 020 3603 7930) principal funder of the Barbican Centre Welcome This evening we’re delighted to welcome It was a revolutionary work in several the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra and respects: drawing exclusively on passages Zürcher Sing-Akademie together with four from the Bible, Handel made the most of outstanding vocal soloists under the his experience as an opera composer in direction of Trevor Pinnock. The concert creating a compelling drama, with the features a single masterpiece: Handel’s chorus taking an unusually central role. To Messiah. the mix, this most cosmopolitan of figures added the full gamut of national styles, It’s a work so central to the repertoire that from the French-style overture via the it’s easy to forget that it was written at a chorale tradition of his native Germany to time when Handel’s stock was not exactly the Italianate ‘Pastoral Symphony’. -

EC-Bach Perfection Programme-Draft.Indd

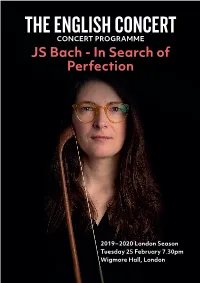

THE ENGLISH CONCE∏T 1 CONCERT PROGRAMME JS Bach - In Search of Perfection 2019 – 2020 London Season Tuesday 25 February 7.30pm Wigmore Hall, London 2 3 WELCOME PROGRAMME Wigmore Hall, More than any composer in history, Bach The English Concert 36 Wigmore Street, Orchestral Suite No 4 in D Johann Sebastian Bach is renowned Laurence Cummings London, W1U 2BP BWV 1069 Director: John Gilhooly for having frequently returned to his Guest Director / The Wigmore Hall Trust own music. Repurposing and revising it Bach Harpsichord Registered Charity for new performance contexts, he was Sinfonia to Cantata 35: No. 1024838. Lisa Beznosiuk Geist und Seele wird verwirret www.wigmore-hall.org.uk apparently unable to help himself from Flute Disabled Access making changes and refinements at Bach and Facilities Tabea Debus Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D every level. Recorder BWV 1050 Tom Foster In this programme, we explore six of Wigmore Hall is a no-smoking INTERVAL Organ venue. No recording or photographic Bach’s most fascinating works — some equipment may be taken into the Sarah Humphrys auditorium, nor used in any other part well known, others hardly known at of the Hall without the prior written Bach Recorder permission of the Hall Management. all. Each has its own story to tell, in Sinfonia to Cantata 169: Wigmore Hall is equipped with a Tuomo Suni ‘Loop’ to help hearing aid users receive illuminating Bach’s working processes Gott soll allein mein Herze haben clear sound without background Violin and revealing how he relentlessly noise. Patrons can use the facility by Bach switching their hearing aids over to ‘T’. -

Journal of the Conductors Guild

Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 2015-2016 19350 Magnolia Grove Square, #301 Leesburg, VA 20176 Phone: (646) 335-2032 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.conductorsguild.org Jan Wilson, Executive Director Officers John Farrer, President John Gordon Ross, Treasurer Erin Freeman, Vice-President David Leibowitz, Secretary Christopher Blair, President-Elect Gordon Johnson, Past President Board of Directors Ira Abrams Brian Dowdy Jon C. Mitchell Marc-André Bougie Thomas Gamboa Philip Morehead Wesley J. Broadnax Silas Nathaniel Huff Kevin Purcell Jonathan Caldwell David Itkin Dominique Royem Rubén Capriles John Koshak Markand Thakar Mark Crim Paul Manz Emily Threinen John Devlin Jeffery Meyer Julius Williams Advisory Council James Allen Anderson Adrian Gnam Larry Newland Pierre Boulez (in memoriam) Michael Griffith Harlan D. Parker Emily Freeman Brown Samuel Jones Donald Portnoy Michael Charry Tonu Kalam Barbara Schubert Sandra Dackow Wes Kenney Gunther Schuller (in memoriam) Harold Farberman Daniel Lewis Leonard Slatkin Max Rudolf Award Winners Herbert Blomstedt Gustav Meier Jonathan Sternberg David M. Epstein Otto-Werner Mueller Paul Vermel Donald Hunsberger Helmuth Rilling Daniel Lewis Gunther Schuller Thelma A. Robinson Award Winners Beatrice Jona Affron Carolyn Kuan Jamie Reeves Eric Bell Katherine Kilburn Laura Rexroth Miriam Burns Matilda Hofman Annunziata Tomaro Kevin Geraldi Octavio Más-Arocas Steven Martyn Zike Theodore Thomas Award Winners Claudio Abbado Frederick Fennell Robert Shaw Maurice Abravanel Bernard Haitink Leonard Slatkin Marin Alsop Margaret Hillis Esa-Pekka Salonen Leon Barzin James Levine Sir Georg Solti Leonard Bernstein Kurt Masur Michael Tilson Thomas Pierre Boulez Sir Simon Rattle David Zinman Sir Colin Davis Max Rudolf Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 (2015-2016) Nathaniel F. -

1) Musikstunde

__________________________________________________________________________ 2 SWR 2 Musikstunde Dienstag, den 10. Januar 2012 Mit Susanne Herzog Il prete rosso Vivaldi, der Lehrer Kulturinteressierte Venedigreisende haben heutzutage ihren Dumont im Gepäck: damit etwa keine Fragen offen bleiben, wenn man sich angestrengt den Kopf verrenkt, um die Tintoretto Deckengemälde in der Scuola di San Rocco zu bewundern oder um die Details von Tizians Assunta in der Frarikirche zu verstehen. Schon zu Vivaldis Zeiten kamen unglaubliche Mengen an Besuchern nach Venedig: in Stosszeiten soviel wie die Hälfte der Bevölkerung der schwimmenden Stadt. Allerdings nicht nur der kunsthistorischen Schätze wegen, sondern durchaus auch um die Musik Venedigs zu genießen. Und diesbezüglich sprach Vincenzo Coronelli in seinem Reiseführer für Venedig in der Ausgabe von 1706 eine ganz klare Empfehlung aus: „Unter den besseren Geigern sind einzigartig Giovanni Battista Vivaldi und sein Sohn, der Priester.“ Vater und Sohn Vivaldi also galten als Geigenstars. Kaum anders ist es auch zu verstehen, dass Vivaldi mit nur fünfundzwanzig Jahren im Ospedale della Pietà Maestro di Violino wurde. Nicht nur die dortigen Mädchen allerdings kamen in den Genuss seines Unterrichts, sondern schon etablierte Geiger wie etwa der spätere Dresdner Konzertmeister Johann Georg Pisendel nahmen private Geigenstunden bei Vivaldi, um sich zu vervollkommnen. Vivaldi als Lehrer: das ist heute das Thema der SWR 2 Musikstunde. Und dass man nicht nur von einem real anwesenden Lehrer etwas lernen kann, sondern dass auch Noten selbst sprechen, dazu am Ende dieser Stunde noch mehr. 1’25 2 3 Musik 1 Antonio Vivaldi Erster Satz aus Concerto B-dur, RV 368 <16> 3’45 Anton Steck, Violine Modo Antiquo Federico Maria Sardelli Titel CD: Concerti per violino II ‘Di sfida’ Naïve, OP 30427, LC 5718 Privat CD Anton Steck, einer der großen Barockgeiger unserer Zeit hat über dieses Konzert Vivaldis gesagt, da gäbe es Passagen, die würde man eigentlich eher bei Paganini erwarten. -

Jean-Philippe Billarant Président Du Conseil D'administration Brigitte Marger Directeur Général

Jean-Philippe Billarant président du conseil d’administration Brigitte Marger directeur général sommaire Après la Tchaikovsky experience menée en mars 1998, Sir Roger Norrington revient à la cité de la musique pour interpréter le Gustav Mahler de la première période dans son contexte historique (influences, effectifs, tempos, facture des ins- truments…) et tenter de retrouver la saveur de l’original. Au cours du même samedi 29 septembre - 16h30 p. 7 week-end, l’éminent biographe de Mahler, Henry-Louis de la Grange, donne une concert-atelier conférence sur « les paradoxes de Mahler » (dimanche à 15h). œuvres de Gustav Mahler Bernarda Fink, mezzo-soprano solistes de l’Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment samedi 29 septembre - 20h p. 14 concert œuvres de Richard Wagner et Anton Bruckner Sir Roger Norrington, direction Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment dimanche 30 septembre - 15h p. 20 conférence les paradoxes de Mahler Henry-Louis de La Grange, conférencier dimanche 30 septembre - 16h30 p. 21 concert œuvres de Gustav Mahler Sir Roger Norrington, direction Christopher Maltman, baryton Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment biographies p. 27 Mahler experience Mahler experience Mahler experience Comme j’ai désormais l’habitude de le faire, le principe Pour retrouver l’esprit original de la musique de Gustav de l’« experience » consiste à réévaluer l’interprétation Mahler, d’autres aspects méritent d’être discutés. J’ai que nous avons des chefs-d’œuvre romantiques pour choisi de renouer, pour ces concerts, avec la dispo- tenter de les faire sonner en fonction de leur époque sition que la plupart des grandes formations prati- d’origine.