Historical Performance Practice at the Beginning of the New Millennium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andreas Scholl: «La Música De Bach Va Dirigida Al Alma Del Oyente

ENTREVISTAS EN LÍNEA “Bach es, sin duda, el compositor más difícil para la voz” Fotos: James McMillan/Decca Andreas Scholl: “La música de Bach va dirigida al alma del oyente” por Lorena Jiménez Alonso l oeste del casco antiguo de Leipzig y rodeada del paraje natural del Johannapark, se encuentra la Lutherkirche; la iglesia que lleva el nombre del teólogo alemán Martín Lutero, artífice de la Reforma Protestante, y quien a principios del siglo AXVI acabó con la hegemonía católica en Europa. Esta entrevista tiene lugar en un banco de la nave lateral de la Iglesia Luterana, minutos después de que Andreas Scholl, acompañado al clavecín por George Christoph Biller (decimosexto Thomaskantor después de J. S. Bach), cantase con el público la música que Johann Sebastian Bach escribió en esta ciudad para el culto dominical luterano. julio-agosto 202 pro ópera La participación vocal activa de los asistentes, dispuestos en Thomaskirche (Iglesia de Santo Tomás). Fue algo increíble, muy diferentes bancos de la iglesia según sus voces: sopranos, emotivo; en esta iglesia te sientes muy cerca de Bach. Es el lugar mezzosopranos, contraltos, tenores, barítonos y bajos, como para el que Bach creó su obra; estás en el mismo lugar para el coristas del que para muchos es hoy el contratenor actual más que Bach compuso la música que estás cantando y eso es algo importante del mundo, es uno de los muchos eventos musicales extraordinario. que se organizan durante el Bachfest Leipzig; festival de referencia en toda Alemania que durante diez días reúne a los Además, en este festival tienes la oportunidad de trabajar mejores artistas internacionales de música barroca. -

Septem Verba a Christo

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PERGOLESI Septem verba a Christo SOPHIE KARTHÄUSER CHRISTOPHE DUMAUX JULIEN BEHR KONSTANTIN WOLFF RENÉ JACOBS FRANZ LISZT Verbum I: Pater, dimitte illis: non enim sciunt qui faciunt (Luke 23:34) 1 | Christus (bass) Recitativo Huc, o dilecti filii 1’57 2 | Aria En doceo diligere 4’38 3 | Anima (alto) Aria Quod iubes, magne Domine 4’02 Verbum II: Amen dico tibi: hodie mecum eris in Paradiso (Luke 25:43) 4 | Christus (tenor) Recitativo Venite, currite 0’55 5 | Aria Latronem hunc aspicite 4’23 6 | Anima (soprano) Aria Ah! peccatoris supplicis 5’04 Verbum III: Mulier ecce filius tuus (John 19:26) 7 | Christus (bass) Recitativo Quo me, amor? 2’01 8 | Aria Dilecta Genitrix 3’35 9 | Anima (soprano) Recitativo Servator optime 1’18 10 | Aria Quod iubes, magne Domine 5’59 Verbum IV: Deus meus, deus meus, ut quid dereliquisti me? (Mark 15:34) 11 | Christus (bass) Aria Huc oculos 5’57 12 | Anima (alto) Aria Afflicte, derelicte 5’40 Verbum V: Sitio (John 19:28) 13 | Christus (bass) Aria O vos omnes, qui transitis 5’19 14 | Anima (tenor) Aria Non nectar, non vinum, non undas 4’13 Verbum VI: Consummatum est (John 19:29) 15 | Christus (bass) Aria Huc advolate mortales 6’09 16 | Anima (soprano) Aria Sic consummasti omnia 5’35 Verbum VII: Pater, in manus tuas commendo spiritum meum (Luke 23:44-46) 17 | Christus (bass) Recitativo Quotquot coram cruce statis 1’36 18 | Aria In tuum, Pater, gremium 5’33 19 | Anima (tenor) Aria Quid ultra peto vivere 6’25 Soprano Sophie Karthäuser Countertenor Christophe Dumaux Tenor Julien Behr Bass Konstantin -

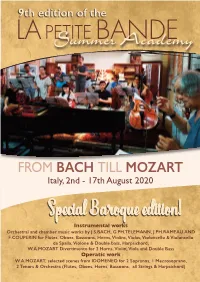

Summer Academy Fee the Academy Fee Is 540 € for Each Participant

9th edition of the LA PESTuITmE mBerA ANcaDdEemy FROM BACH TILL MOZART Italy, 2nd - 17th August 2020 SpeciIanstlr uBmenatarl woorqks ue edition! Orchestral and chamber music works by J.S.BACH, G.PH.TELEMANN, J.PH.RAMEAU AND F.COUPERIN for Flutes, Oboes, Bassoons, Horns, Violins, Violas, Violoncello & Violoncello da Spalla, Violone & Double bass, Harpsichord; W.A.MOZART Divertimento for 2 Horns, Violin, Viola and Double Bass Operatic work W.A.MOZART, selected scenes from IDOMENEO for 2 Sopranos, 1 Mezzosoprano, 2 Tenors & Orchestra (Flutes, Oboes, Horns, Bassoons, all Strings & Harpsichord) LA PESTuITmE mBerA ANcaDdEemy Since 2012, La Petite BandeA orgpanpizleis caa yetairolyn Susm mforer A c2ad0em2y 0in Itaalyr, ew hnicho wwith othpe eyenar! s has become a beloved international appointment for many musicians desiring to deepen their knowledge and practice of historically informed practice for the baroque and classical repertoire (especially Mozart & Haydn). Indeed, they have taken their chance to work with one of the pioneers of this field, violinist and leader of La Petite Bande, Sigiswald Kuijken. Each year, the Academy focuses both on instrumental and operatic works. Singers work with Marie Kuijken on a historically informed approach to the textual and scenical aspects of the score, and perform the opera with the orchestra. The 2020 edition is a special BAROQUE edition, in which the instrumental focus will be on orchestral and chamber music works of J.S.Bach, G.Telemann, J.Ph.Rameau aBnda F.rCooupqeruine. By choosing mostly to play one-to-a-part, for these works the difference between orchestral and chambermusic playing will be minimal. -

Faculty Recital Piano Vs. Viola: a Romantic Duel Jasmin Arakawa, Piano Rudolf Haken, Five-String Viola ______

Faculty Recital Piano vs. Viola: A Romantic Duel Jasmin Arakawa, piano Rudolf Haken, five-string viola ________________________________ Sonata in E-flat Major, op. 120, no. 2 (1894) Johannes Brahms Allegro amabile (1833-1897) Allegro appassionato Andante con moto; Allegro Grandes études de Paganini (1851) Franz Liszt No. 5 (1811-1986) No. 2 No. 3 “La Campanella” Caprices (ca. 1810) Niccolò Paganini (1833-1897) No. 9 arranged by Rudolf Haken No. 17 “La Campanella” from Violin Concerto No.2 (1826) INTERMISSION Concerto in F (2014) Rudolf Haken Possum Trot (b. 1965) Triathlon Hoedown Walpurgisnacht Le Grand Tango (1982) Ástor Piazzolla (1921-1992) ________________________________ The Fourth Concert of Academic Year 2014-2015 Tuesday, September 16, 2014 7:30 p.m. A charismatic and versatile pianist, Jasmin Arakawa has performed widely in North America, Central and South America, Europe, and Japan. Described by critics as a “lyrical” pianist with “impeccable technique” (The Record), she has been heard in prestigious venues worldwide including Carnegie Hall, Salle Gaveau (Paris) and Victoria Hall (Geneva). She has appeared as a concerto soloist with the Philips Symphony Orchestra in Amsterdam, and with the Piracicaba Symphony Orchestra in Brazil. Arakawa’s interest in Spanish repertoire grew out of a series of lessons with Alicia de Larrocha in 2004. She has subsequently recorded solo and chamber pieces by Spanish and Latin American composers (LAMC Record), under the sponsorship of the Spanish Embassy as a prizewinner at the Latin American Music Competition. An avid chamber musician, she has collaborated with such artists as cellists Colin Carr and Gary Hoffman, flutists Jean Ferrandis and Marina Piccinini, clarinetist James Campbell, and the Penderecki Quartet. -

French Underground Raves of the Nineties. Aesthetic Politics of Affect and Autonomy Jean-Christophe Sevin

French underground raves of the nineties. Aesthetic politics of affect and autonomy Jean-Christophe Sevin To cite this version: Jean-Christophe Sevin. French underground raves of the nineties. Aesthetic politics of affect and autonomy. Political Aesthetics: Culture, Critique and the Everyday, Arundhati Virmani, pp.71-86, 2016, 978-0-415-72884-3. halshs-01954321 HAL Id: halshs-01954321 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01954321 Submitted on 13 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. French underground raves of the 1990s. Aesthetic politics of affect and autonomy Jean-Christophe Sevin FRENCH UNDERGROUND RAVES OF THE 1990S. AESTHETIC POLITICS OF AFFECT AND AUTONOMY In Arundhati Virmani (ed.), Political Aesthetics: Culture, Critique and the Everyday, London, Routledge, 2016, p.71-86. The emergence of techno music – commonly used in France as electronic dance music – in the early 1990s is inseparable from rave parties as a form of spatiotemporal deployment. It signifies that the live diffusion via a sound system powerful enough to diffuse not only its volume but also its sound frequencies spectrum, including infrabass, is an integral part of the techno experience. In other words listening on domestic equipment is not a sufficient condition to experience this music. -

ANDREAS SCHOLL Sydney Recital Hall and the Gran Teatre Del Liceu, Barcelona

TAMAR HALPERIN Tamar Halperin was born in Israel and studied at Tel Aviv University, the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, Basel, and the Juilliard School, New York, where she obtained a doctorate in 2009. Her repertory focuses on Baroque music, but she is also an enthusiastic performer of classical and contemporary THOMAS W. BUSSE music: she composes, arranges and performs popular, jazz and FUND PRESENTS electronic music, some of which has been recorded on the Act and Garage labels. Her collaboration with the jazz pianist Michael Wollny led to the album Wunderkammer, which won the 2010 ECHO Klassik Award for best piano album. As a soloist and chamber musician she has performed in Israel, Europe, United States, Mexico, Japan, Korea and Australia, appearing in many prestigious venues, including Carnegie Hall and Alice Tully Hall, New York, the Wigmore Hall, the Musashino Hall in Tokyo, the ANDREAS SCHOLL Sydney Recital Hall and the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona. She has collaborated with Laurence Cummings, the New countertenor York Philharmonic Orchestra, and the London-based Serafin Camerata Orchestra. Her numerous prizes and awards include an honorary prize at the 2004 Van Vlaanderen Musica Antiqua Brugge Competition, the Presser Award in 2005, the REC Music Award in 2006 and the Eisen-Picard Performing Arts Award in 2006 and 2007. Tamar Halperin, piano Wednesday, October 1, 2014 Corbett Auditorium 8:00 p.m. This performance is supported by the Thomas W. Busse Trust. CCM has become an All-Steinway School through the kindness of its donors. A generous gift by Patricia A. Corbett in her estate plan has played a key role in making this a reality. -

Musicians from Abroad and Their World Renowned Czech Counterparts to Pay Tribute to One of the Greatest Musical Geniuses During the Dvořák Prague Festival

Musicians from Abroad and Their World Renowned Czech Counterparts to Pay Tribute to One of the Greatest Musical Geniuses during the Dvořák Prague Festival Prague, 28 March 2017 – The Dvořák Prague International Music Festival has unveiled the program and began advance sale of tickets for the 10th anniversary season. The event, which bears the name of one of the greatest music composers, will showcase renowned soloists and some of the world's best orchestras and conductors during 7-23 September 2017. Apart from Antonín Dvořák's well- and lesser-known works, the festival will present the music of other composers from different eras. The event will feature star vocalists from the Metropolitan Opera and other prestigious establishments, such as Kristine Opolais, Piotr Beczala, René Pape, Michael Spyres, Adam Plachetka, and Jan Martiník. World-renowned orchestras performing at the festival will include the London Philharmonic Orchestra with chief conductor Vladimir Jurowski and the Essen Philharmonic with conductor Tomáš Netopil, who will also conduct the Vienna Symphony in the closing concert. An extraordinary experience will be a performance delivered by conductor Ingo Metzmacher and the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester, which will feature French piano virtuoso Jean-Yves Thibaudet. The program will include the festival's orchestra in residence, the Czech Philharmonic with conductor Jiří Bělohlávek, the Prague Philharmonia (PKF), and such leading vocal ensembles as the Prague Philharmonic Choir and the Czech Philharmonic Choir of Brno. For the -

Jouer Bach À La Harpe Moderne Proposition D’Une Méthode De Transcription De La Musique Pour Luth De Johann Sebastian Bach

JOUER BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE PROPOSITION D’UNE MÉTHODE DE TRANSCRIPTION DE LA MUSIQUE POUR LUTH DE JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH MARIE CHABBEY MARA GALASSI LETIZIA BELMONDO 2020 https://doi.org/10.26039/XA8B-YJ76. 1. PRÉAMBULE ............................................................................................. 3 2. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 5 3. TRANSCRIRE BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE, UN DÉFI DE TAILLE ................ 9 3.1 TRANSCRIRE OU ARRANGER ? PRÉCISIONS TERMINOLOGIQUES ....................................... 9 3.2 BACH TRANSCRIPTEUR ................................................................................................... 11 3.3 LA TRANSCRIPTION À LA HARPE ; UNE PRATIQUE SÉCULAIRE ......................................... 13 3.4 REPÈRES HISTORIQUES SUR LA TRANSCRIPTION ET LA RÉCEPTION DES ŒUVRES DE BACH AU FIL DES SIÈCLES ....................................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Différences d’attitudes vis-à-vis de l’original ............................................................. 15 3.4.2 La musique de J.S. Bach à la harpe ............................................................................ 19 3.5 LES HARPES AU TEMPS DE J.S. BACH ............................................................................. 21 3.5.1 Panorama des harpes présentes en Allemagne. ......................................................... 21 4. CHOIX DE LA PIECE EN VUE D’UNE TRANSCRIPTION ............................... -

BIOGRAPHIES Violin Faculty Justin Chou Is a Performer, Teacher And

MASTER PLAYERS FESTIVAL: BIOGRAPHIES Violin faculty Justin Chou is a performer, teacher and concert producer. He has assisted and performed in productions such as the Master Players Concert Series, IVSO 60th anniversary, Asian Invasion recital series combining classical music and comedy, the 2012 TEDxUD event that streamed live across the Internet and personal projects like Violins4ward, which recently produced a concert titled “No Violence, Just Violins” to promote violence awareness and harmonious productivity. Chou’s current project, Verdant, is a spring classical series based in Wilmington, Delaware, that presents innovative concerts by growing music into daily life, combining classical performance with unlikely life passions. As an orchestral musician, he spent three years as concertmaster of the Illinois Valley Symphony, with duties that included solo performances with the orchestra. Chou also has performed in various orchestras in principal positions, including an international tour to Colombia with the University of Delaware Symphony Orchestra, and in the state of Wisconsin, with the University of Wisconsin Symphony Orchestra, the Lake Geneva Symphony Orchestra and the Beloit-Janesville Symphony. Chou received his master of music degree from UD under Prof. Xiang Gao, with a full assistantship, and his undergraduate degree from the University of Wisconsin, with Profs. Felicia Moye and Vartan Manoogian, where he received the esteemed Ivan Galamian Award. Chou also has received honorable mention in competitions like the Milwaukee Young Artist and Youth Symphony Orchestras competitions. Xiang Gao, MPF founding artistic director Recognized as one of the world's most successful performing artists of his generation from the People's Republic of China, Xiang Gao has solo performed for many world leaders and with more than 100 orchestras worldwide. -

VIVACE AUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Photo © Martin Kubica Photo

VIVACEAUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Classical music review in Supraphon recordings Photo archive PPC archive Photo Photo © Jan Houda Photo LUKÁŠ VASILEK SIMONA ŠATUROVÁ TOMÁŠ NETOPIL Borggreve © Marco Photo Photo © David Konečný Photo Photo © Petr Kurečka © Petr Photo MARKO IVANOVIĆ RADEK BABORÁK RICHARD NOVÁK CP archive Photo Photo © Lukáš Kadeřábek Photo JANA SEMERÁDOVÁ • MAREK ŠTRYNCL • ROMAN VÁLEK Photo © Martin Kubica Photo XENIA LÖFFLER 1 VIVACE AUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Photo © Martin Kubica Photo Dear friends, of Kabeláč, the second greatest 20th-century Czech symphonist, only When looking over the fruits of Supraphon’s autumn harvest, I can eclipsed by Martinů. The project represents the first large repayment observe that a number of them have a common denominator, one per- to the man, whose upright posture and unyielding nature made him taining to the autumn of life, maturity and reflections on life-long “inconvenient” during World War II and the Communist regime work. I would thus like to highlight a few of our albums, viewed from alike, a human who remained faithful to his principles even when it this very angle of vision. resulted in his works not being allowed to be performed, paying the This year, we have paid special attention to Bohuslav Martinů in price of existential uncertainty and imperilment. particular. Tomáš Netopil deserves merit for an exquisite and highly A totally different hindsight is afforded by the unique album acclaimed recording (the Sunday Times Album of the Week, for of J. S. Bach’s complete Brandenburg Concertos, which has been instance), featuring one of the composer’s final two operas, Ariane, released on CD for the very first time. -

Music in the Pavilion

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA LIBRARIES KISLAK CENTER Music in the Pavilion PHOTO BY SHARON TERELLO NIGHT MUSIC A SUBTLE AROMA OF ROMANTICISM Friday, September 27, 2019 Class of 1978 Orrery Pavilion Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center www.library.upenn.edu/about/exhibits-events/music-pavilion .................................................................................. .................................................................................. .................................................................................. .................................................................................................................................................................... .................................................................................. ........... ............ ......... A SUBTLE AROMA OF ROMANTICISM NIGHT MUSIC Andrew Willis, piano Steven Zohn, flute Rebecca Harris, violin Amy Leonard, viola Eve Miller, cello Heather Miller Lardin, double bass PIANO TRIO IN D MINOR, OP. 49 (1840) FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–47) MOLTO ALLEGRO AGITATO ANDANTE CON MOTO TRANQUILLO SCHERZO: LEGGIERO E VIVACE FINALE: ALLEGRO ASSAI APPASSIONATO PIANO QUINTET IN A MINOR, OP. 30 (1842) LOUISE FARRENC (1804–75) ALLEGRO ADAGIO NON TROPPO SCHERZO: PRESTO FINALE: ALLEGRO The piano used for this concert was built in 1846 by the Paris firm of Sébastien Érard. It is a generous gift to the Music Department by Mr. Yves Gaden (G ’73), in loving memory of his wife Monique (1950-2009). ................................................................................... -

La Petite Bande Olv

2007-2008 BLAUWE ZAAL DO 24 APRIL 2008 La Petite Bande olv. Sigiswald Kuijken 2007-2008 Bach wo 14 november 2007 KOOR & ORKEST COLLEGIUM VOCALE GENT OLV. PHILIppE HERREWEGHE za 15 december 2007 FREIBURGER BAROckORCHESTER & COLLEGIUM VOCALE GENT OLV. MASAAKI SUZUKI do 24 april 2008 LA PETITE BANDE OLV. SIGISWALD KUIJKEN Bach LA PETITE BANDE SIGISWALD KUIJKEN muzikale leiding SIRI THORNHILL sopraan PETRA NOskAIOVÁ mezzo CHRISTOPH GENZ tenor JAN VAN DER CRAbbEN bas JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) Cantate ‘Es ist euch gut, dass ich hingehe’, BWV108 20’ Pictogrammen DeSingel AUDIO gelieve uw GSM uit te schakelen Cantate ‘Wahrlich, wahrlich, ich sage euch’, BWV86 18’ Cantate ‘Sie werden euch in den Bann tun’, BWV44 22’ pauze De inleidingen kan u achteraf beluisteren via www.desingel.be Selecteer hiervoor voorstelling/concert/tentoonstelling van uw keuze. Himmelfahrtsoratorium REAGEER ‘Lobet Gott in seinen Reichen’, BWV11 32’ & WIN Op www.desingel.be kan u uw visie, opinie, commentaar, appreciatie, … betreffende het programma van deSingel met andere toeschouwers delen. Selecteer hiervoor voorstelling/ concert/tentoonstelling van uw keuze. Neemt u deel aan dit forum, dan maakt u meteen kans om tickets te winnen. Bij elk concert worden cd’s te koop aangeboden door ’t KLAverVIER, Kasteeldreef 6, Schilde, 03 384 29 70 > www.tklavervier.be foyer deSingel enkel open bij avondvoorstellingen in rode en/of blauwe zaal open vanaf 18.40 uur kleine koude of warme gerechten te bestellen vóór 19.20 uur broodjes tot net vóór aanvang van de voorstellingen