A Philosophical Analysis of Pacific Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting by High School: Identity Formation and the Educational Achievements of Punjabi Young Men in Surrey, B.C

GETTING BY HIGH SCHOOL: IDENTITY FORMATION AND THE EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENTS OF PUNJABI YOUNG MEN IN SURREY, B.C. by HEATHER DANIELLE FROST M.A., The University of Toronto, 2002 B.A., The University of Toronto, 2000 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2010 © Heather Danielle Frost, 2010 Abstract This thesis is concerned with the lives and educational achievements of young Indo-Canadians, specifically the high school aged sons of Punjabi parents who immigrated to Canada beginning in the 1970s, and who were born or who have had the majority of their schooling in Canada‟s public school system. I examine how these young people develop and articulate a sense of who they are in the context of their parents‟ immigration and the extent to which their identities are determined and conditioned by their everyday lives. I also grapple with the implications of identity formation for the educational achievements of second generation youth by addressing how the identity choices made by young Punjabi Canadian men influence their educational performances. Using data collected by the Ministry of Education of British Columbia, I develop a quantitative profile of the educational achievements of Punjabi students enrolled in public secondary schools in the Greater Vancouver Region. This profile indicates that while most Punjabi students are completing secondary school, many, particularly the young men, are graduating with grade point averages at the lower end of the continuum and are failing to meet provincial expectations in Foundation Skills Assessments. -

South Pacific Beats PDF

Connected South Pacific Beats Level 3 by Veronika Meduna 2018 Overview This article describes how Wellington designer Rachael Hall developed a modern version of the traditional Tongan lali. Called Patō, Rachael’s drum keeps the traditional sound of a lali but incorporates digital capabilities. Her hope is that Patō will allow musicians to mix traditional Pacific sounds with modern music. A Google Slides version of this article is available at www.connected.tki.org.nz This text also has additional digital content, which is available online at www.connected.tki.org.nz Curriculum contexts SCIENCE: Physical World: Physical inquiry and Key Nature of science ideas physics concepts Sound is a form of energy that, like all other forms of energy, can be transferred or transformed into other types of energy. Level 3 – Explore, describe, and represent patterns and trends for everyday examples of physical phenomena, Sound is caused by vibrations of particles in a medium (solid, such as movement, forces … sound, waves … For liquid, or gas). example, identify and describe the effect of forces (contact Sound waves can be described by their wavelength, frequency, and non-contact) on the motion of objects … and amplitude. The pitch of a sound is related to the wavelength and frequency – Science capabilities long or large vibrating objects tend to produce low sounds; short or small vibrating objects tend to produce high sounds. This article provides opportunities to focus on the following science capabilities: The volume of a sound depends on how much energy is used to create the sound – louder sounds have a bigger amplitude but the Use evidence frequency and pitch will be the same whether a given sound is Engage with science. -

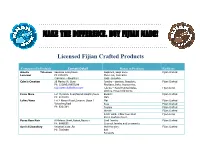

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

Experiences of Muslim Female Students in Knoxville: at the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Religion

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2018 Experiences of Muslim Female Students in Knoxville: At the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Religion Nuray Karaman University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Karaman, Nuray, "Experiences of Muslim Female Students in Knoxville: At the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Religion. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2018. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5002 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Nuray Karaman entitled "Experiences of Muslim Female Students in Knoxville: At the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Religion." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sociology. Michelle M. Christian, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Manuela Ceballos, Harry F. Dahms, Asafa Jalata Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Experiences of Muslim Female Students in Knoxville: At the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Religion A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Nuray Karaman August 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Nuray Karaman. -

JBH the Art of the Drum

THE ART OF THE DRUM: THE RELIGIOUS AND SPIRITUAL DYNAMIC OF DRUMMING AND DRUM CRAFTING IN FIJI, JAPAN, INDIA, MOROCCO AND CUBA JESSE BROWNER-HAMLIN THE BRISTOL FELLOWSHIP HAMILTON COLLEGE WWW.THEARTOFTHEDRUM.BLOGSPOT.COM AUGUST 2007 – AUGUST 2008 2 In the original parameters of my Bristol Fellowship, I aspired to investigate the religious and spiritual dynamic of drumming and drum crafting in Fiji, Japan, India, Morocco, the Dominican Republic, and Trinidad and Tobago. As any academic will attest, field research tends to march to beat of its own drum, if you will. The beauty of my fellowship was that I could have conducted the research in just about any country in the world. Music is everywhere; and moreover, drums are the oldest instrument known to man. Along the way, I modestly altered the itinerary: in the end, I conducted research in Fiji, Japan, India, Western Europe, Morocco and Cuba. It truly was a remarkable experience to have full autonomy over my research: I am infinitely grateful that the Bristol Family and Hamilton College (represented by Ginny Dosch) gave me the freedom to modify my itinerary as I saw fit. To be successful while conducting field research, you need to be flexible. While several of my hypotheses from my proposal were examined and tested, I often found myself in unscripted situations. The daily unpredictability of the fellowship is what makes it such a profound and exciting experience, as every day is an adventure. With the blessing of technology, this fellowship was carried out in “real time.” Because I actively maintained a website, www.theartofthedrum.blogspot.com, my research and multimedia were posted almost instantaneously, and thus, my family and friends back in the States could read about my experiences, see my pictures and watch my videos. -

Intergenerational Conversations in a South Asian – Canadian Family

Negotiating Identity: Intergenerational Conversations in a South Asian – Canadian Family Sonia Dhaliwal A Thesis In the Department Of History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2020 © Sonia Dhaliwal, 2020 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Sonia Dhaliwal Entitled: “Negotiating Identity: Intergenerational Conversations in a South Asian-Canadian Family and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) and complies with the rules of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining committee _______________________________ Chair Dr. Peter Gossage ________________________________ Examiner Dr. Rachel Berger ________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cynthia Hammond ________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Barbara Lorenzkowski Approved by ______________________________________ Dr. Peter Gossage, Interim Graduate Program Director ________________, 2020 ________________________________________________ Dr. Pascale Sicotte, Dean of the Faculty of Arts & Science iii Abstract Negotiating Identity: Intergenerational Conversations in a South Asian – Canadian Family Sonia Dhaliwal This thesis investigates change over time within a diasporic community in Canada using oral history methodologies with four generations of a South Asian-Canadian family. Using -

The Oxford Democrat

how s rou* inmr • la lb# (omlr opara of Th* .Mikalo Hla Imperial lligbnaaa u>« T« H«k*, U> MM rlMI, km«i *nl Litw A lunula* u»»r or kMBlMt ■MITlMfnl" A nobler taak tbu makleg a*M BlMi rlveraof kunlwi urrlatil mpttm. If king or laymaa. con 1.1 take npon hi«a» Th« Hear among the iwlnu «u contid md tba Kitrct of all a man a eall Impnl- mi, ao'l U« tkatcn arr ui to ooa l»d»f that If om'i liver la In an ngly condition of dlaconteat, ton* one a bead will be muh.il before il|kt •' to lb* llow a your Uvaf I la niilriltot aa to ■ |««"| llffin alwl «l hit* Inquiry Arc yoa a tear or angel iMiRICl a *bk n«il« *11 Ihlnj* l.Tl KAI. »o J i «•*•« la If* of CARD BKIOADK. ^.irati' >'W»d«jr. thr ■' ORPARTMKNT m* I4M il, which THK POSTAL ■ pD|*l« •la* A • Ira tntli*rt.-* >b u In h.-r fK In t&a wrf» inter am- hi-* uv-nl ««<4i him lla 1.1, of tb« th**p ktllail I .tail, » M put Niao-uatba "paranaaailaia*." • IU4 »h• «*, or Irlnwl -h-- -a•> (o (aal Comv itmi ■« R bat tt« 4<«« iikirl AFFAIR iMd Uu<«|h tla«l.air anH •tl<Vik fMI ihr actloM for divorce. tba cartaia l*c Wutn V> kta> Ntiptil laat A FAMILY »r« Oar rrp.>n of tbr Kalr. w**h, Ml tkM) IUi|i llufi haial tb» of Itrittad I |rf«i rat ail h • I m*>. -

Gypsies Tramps and Theives Final

i Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves: The Contrapuntal Rantings of a Halfbreed Girl by Allyson K. Anderson A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Native Studies University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2019 by Allyson Anderson ii Abstract This thesis investigates issues of representation and the social identity of the colonized by conducting a textual analysis of a fictive social construct that I dub the halfbreed girl, and of the ways in which selected metisse writers, poets, artists and performers respond to that stereotype in their respective works. Using methodologies in literature and the visual/performing arts, this thesis interrogates matters of social process: specifically, settler-colonialism’s discursive management of the social identities – in effect, the social place – of metis women, and how metis women negotiate this highly raced and gendered identity space. Emphasizing Canadian contexts, the images examined are drawn from North American settler-colonial pop-culture texts produced in the late nineteenth- through the early twenty-first centuries; the metisse responses to them are gathered from the same time period. The thesis includes American-produced images of the halfbreed girl due to the historic relationship between the two nations and the significant consumption of mass-produced American pop-culture media by Canadians – historically and currently. The first tier of the study demonstrates how the figure of the halfbreed girl is rendered abject through textual strategies that situate her at the intersection of the dichotomies, civilization/savagery and Madonna/whore, generating the racialized Princess/squaw polemic. -

From Conformity to Protest: the Evolution of Latinos in American Popular Culture, 1930S-1980S

From Conformity to Protest: The Evolution of Latinos in American Popular Culture, 1930s-1980s A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2017 by Vanessa de los Reyes M.A., Miami University, 2008 B.A., Northern Kentucky University, 2006 Committee Chair: Stephen R. Porter, Ph.D. Abstract “From Conformity to Protest” examines the visual representations of Latinos in American popular culture—specifically in film, television, and advertising—from the 1930s through the early 1980s. It follows the changing portrayals of Latinos in popular culture and how they reflected the larger societal phenomena of conformity, the battle for civil rights and inclusion, and the debate over identity politics and cultural authenticity. It also explores how these images affected Latinos’ sense of identity, particularly racial and ethnic identities, and their sense of belonging in American society. This dissertation traces the evolution of Latinos in popular culture through the various cultural anxieties in the United States in the middle half of the twentieth century, including immigration, citizenship, and civil rights. Those tensions profoundly transformed the politics and social dynamics of American society and affected how Americans thought of and reacted to Latinos and how Latinos thought of themselves. This work begins in the 1930s when Latin Americans largely accepted portrayals of themselves as cultural stereotypes, but longed for inclusion as “white” Americans. The narrative of conformity continues through the 1950s as the middle chapters thematically and chronologically examine how mainstream cultural producers portrayed different Latino groups—including Chicanos (or Mexican Americans), Puerto Ricans, and Cubans. -

Australian CD Project

'tX) rlrt r,,'tl,l ,,1n,,,. \t l(tt "Bring the Past to Present": Recording and Reviving Rotuman Music via a Collaborative RotumaniFijian/ AustralianCD Project Karl Neuenfeldt Abilru(t This ltqter etplores a recordingpr<tjett tltut led to CDs dtx'utnetrtittgRrturtrttrr tnusi- cul per.fortnan<'esand ntusi<'practitt' in Snva,Fiji. The pro.jectn:us u t'ollulxtrution befw'eenthe Rottmnn tliusporiccttnunuttit,-, the'Ot'euniu Cetilre.lor the Art,sund Cul- ture ut tlk Universitl'oJ'the South PaL'itit und a nrusic-busedresearcher Jrotn Austru- liu. It usesdescriptitsn, unaltsis und ethnogruplt,-Io e.rpktrethe role oJ'digitaltechnol- og,ies;tht' role untl ewtlutiottol ntusiL'in tliasporiccotnnuuilies in Australia and Fi.ii: tlrc benefit.sutttl L'hallenges of tollulxtrative trunsildtionalmusitul researchpr()je(ts: antl tlrc role oJnusit reseon'hers us rttusit producers. "l think it is veryimportant to know aboutthe old songsand the new ones as wcll. I am a loverof singingand I loveto singchurch hymns and the traditional songs as well. It is also irnportantbecausc I can alwaystell my grandchildlc-nabout the songsof the past anclpresent and thcy might know rvhenthey -qrowup whcthcr anythinghas changed."(Sarote Fesaitu. eldest fernale member of the ChurchwardChlpel's Rotu- man Choir. Suva.Fiji 2004) In recent years an ernerging discourse in music-based studies has coalesced around the interrelationshipsbetween digital recording technologies,cross-cultural collaborative researchproJects and rnusic-researchersoperating as music producers, artistsor entr€preneurs.Greene and Porcello (2005:2) use the term "wired sound" for this phenomenon and discourseand provide the following sunllrary: Recordingstudios have become. among othc'r things. sponge-like centers where the world's soundsare quickly and continuallvabsorbed. -

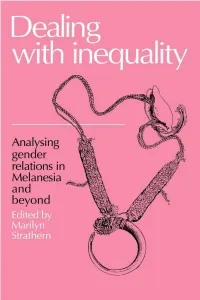

Dealing with Inequality: Analysing Gender Relations in Melanesia And

Dealing with inequality The question of 'equality' between the sexes has been of long-standing interest among anthropologists, yet remains intransigent. This volume sets out not to dispose of the question, but rather to examine how to debate it. It recognises that inequality as a theoretical and practical concern is rooted in Western ideas and concepts, but also that there are palpable differences in power relations existing between men and women in non-Western societies, that are otherwise, in world terms 'egalitarian', and that these need to be accounted for. The volume comprises ten essays by anthropologists who discuss the nature of social inequality between the sexes in societies they know through first-hand fieldwork, mostly, though not exclusively, in Melanesia. This regional focus gives an important coherence to the volume, and highlights the different analytical strategies that the contributors employ for accounting for gender inequality. Running through the essays is a commentary on the cultural bias of the observer, and the extent to which this influences Westerners' judgements about equality and inequality among non-Western peoples. By exploring indigenous concepts of 'agen .:y', the contributors challenge the way in which Western observers wmmonly identify individual and collective action, and the power people daim for themselves, and, surprisingly, show that inequality is not reducible to relations of domination and subordination. The volume as a whole will be provocative reading for anthropologists con.:erned with gender studies and the Pacific, and will be an invaluable resour;;e for anyone who would turn to anthropology for cross-cultural insight into gender relations. -

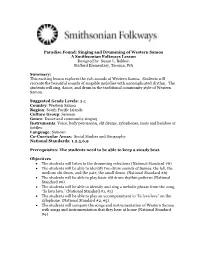

Singing and Drumming of Western Samoa a Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed By: Susan L

Paradise Found: Singing and Drumming of Western Samoa A Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed by: Susan L. Bakken Stafford Elementary, Tacoma, WA Summary: This exciting lesson explores the rich sounds of Western Samoa. Students will recreate the beautiful sounds of singable melodies with uncomplicated rhythm. The students will sing, dance, and drum in the traditional community style of Western Samoa. Suggested Grade Levels: 3-5 Country: Western Samoa Region: South Pacific Islands Culture Group: Samoan Genre: Dance and community singing Instruments: Voice, body percussion, slit drums, xylophones, mats and bamboo or bottles. Language: Samoan Co-Curricular Areas: Social Studies and Geography National Standards: 1,2,5,6,9 Prerequisites: The students need to be able to keep a steady beat. Objectives The students will listen to the drumming selections (National Standard #6) The students will be able to identify two drum sounds of Samoa, the lali, the medium slit drum, and the pate, the small drum. (National Standard #6) The students will be able to play basic slit drum rhythm patterns (National Standard #6) The students will be able to identify and sing a melodic phrase from the song, “Ia lava lava.” (National Standard #1, #5) The students will be able to play an accompaniment to “Ia lava lava” on the xylophone. (National Standard #2, #5) The students will compare the songs and instrumentation of Western Samoa with songs and instrumentation that they hear at home (National Standard #9) Materials: Smithsonian Folkways listening excerpts