Analyzing English Grammar: an Introduction to Feature Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar Traditional grammar refers to the type of grammar study Continuing with this tradition, grammarians in done prior to the beginnings of modern linguistics. the eighteenth century studied English, along with many Grammar, in this traditional sense, is the study of the other European languages, by using the prescriptive structure and formation of words and sentences, usually approach in traditional grammar; during this time alone, without much reference to sound and meaning. In the over 270 grammars of English were published. During more modern linguistic sense, grammar is the study of the most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, grammar entire interrelated system of structures— sounds, words, was viewed as the art or science of correct language in meanings, sentences—within a language. both speech and writing. By pointing out common Traditional grammar can be traced back over mistakes in usage, these early grammarians created 2,000 years and includes grammars from the classical grammars and dictionaries to help settle usage arguments period of Greece, India, and Rome; the Middle Ages; the and to encourage the improvement of English. Renaissance; the eighteenth and nineteenth century; and One of the most influential grammars of the more modern times. The grammars created in this eighteenth century was Lindley Murray’s English tradition reflect the prescriptive view that one dialect or grammar (1794), which was updated in new editions for variety of a language is to be valued more highly than decades. Murray’s rules were taught for many years others and should be the norm for all speakers of the throughout school systems in England and the United language. -

Linguistic Stereotypes

RFFZEM, 32-33(22-23)(1992/93,1993/1994) D. ŠKARA: LINGUISTIC STEREOTYPES:... • LINGUISTIC STEREOTYPES: CROSSCULTURAL ANALYSIS OF PROVERBS DANICA ŠKARA UDK/UDC: 801 Filozofski fakultet u Zadru Izvorni znanstveni članak Faculty of Philosophy in Zadar Original scientific paper Primljeno : 1994-03-30 Received The aim of this paper is to analyse proverbs as linguistic stereotypes from a semantic point of view. The sample of proverbs is randomly chosen from 3 national collections: Croatian, English and Italian. The results of the analysis show that quite a small number of proverbs (about 10%) reflect traditional values and customs which are specific to one culture only. It seems that their universal character makes an ethnocentric approach nearly unacceptable. A high percentage of proverbs (90%) share a very strong mutual resemblance, despite all the differences stemming from ethnic, geographic, historical and language factors. The prevalence of equivalent, synonymous proverbs over specific ones is evident. They differ only in their immagery, in local realia and concepts, but the logical formula of their content is identical. The most frequent sentence structure of the proverbs with universal distrubution is the quadripartite structure and its main feature is symmetry. Does it mean that such sentences can be considered as some kind of kernel sentences? This question asks for additional research. Finally, we can make a conclusion that the universality and transferability are the most prominent features of the proverbs. 1. Introduction It is generally accepted that proverbs represent the smallest verbal folklore genre, but they can be viewed as linguistic units, too. They are used in everyday conversation, journalistic writing, advertising, speeches of all types, in sermons, literature, slogans, songs, and other forms of human communications. -

Learn Pronouns As Part of Speech for Bank & SSC Exams

Learn Pronouns as Part of Speech for Bank & SSC Exams - English Notes in PDF Are you preparing for Banking or SSC Exams? If you aim at making a career in the government sector & get a reputed job, it is very important to know the basics of English Language. To score maximum marks in this section with great accuracy, it is important for you to be prepared with the basic grammar & vocabulary. Here we are with a detailed explanatory article on Pronouns as Part of Speech with relevant examples. So, read the article carefully & then take our Online Mock Tests to check your level of preparation. Before moving ahead with Pronouns, let’s have a look at what are parts of speech in brief: Parts of Speech Parts of speech are the basic categories of words according to their function in a sentence. It is a category to which a word is assigned in accordance with its syntactic functions. English has eight main parts of speech, namely, Nouns, Pronouns, Adjectives, Verbs, Adverbs, Prepositions, Conjunctions & Interjections. In grammar, the parts of speech, also called lexical categories, grammatical categories or word classes is a linguistic category of words. Pronouns as Part of Speech 1 | Pronouns as part of speech are the words which are used in place of nouns like people, places, or things. They are used to avoid sounding unnatural by reusing the same noun in a sentence multiple times. In the sentence Maya saw Sanjay, and she waved at him, the pronouns she and him take the place of Maya and Sanjay, respectively. -

The Function of Phrasal Verbs and Their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals Brock Brady Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brady, Brock, "The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4181. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6065 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brock Brady for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (lESOL) presented March 29th, 1991. Title: The Function of Phrasal Verbs and their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: { e.!I :flette S. DeCarrico, Chair Marjorie Terdal Thomas Dieterich Sister Rita Rose Vistica This study investigates the use of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts (i.e. nouns with a lexical structure and meaning similar to corresponding phrasal verbs) in technical manuals from three perspectives: (1) that such two-word items might be more frequent in technical writing than in general texts; (2) that these two-word items might have particular functions in technical writing; and that (3) 2 frequencies of these items might vary according to the presumed expertise of the text's audience. -

Syntax and Morphology Semantics

Parent Tip Sheet Language Syntax & Morphology yntax is the development of sentence structure meaning your child’s first attempts at putting two words together. SMorphology refers to the structure and construction of words and the rules that determine changes in word meaning; it’s knowing plural forms 9 and correct use of verb tense. Introduce words from many different categories: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions. The emergence of first words 9 typically begins around 12 months of Use the Plus One Rule: add a word to expand the length of your child’s utterance to model longer sentences. Also use correct grammar, even age. Syntax typically begins when if it means adding more than one word. E.g., if your child says ‘blue a child begins to combine words in ball” you can say “The blue ball is big.” early two word utterances (ex. Daddy 9 work) around 18-24 months. Read books with repetition, such as: We’re Going on a Bear Hunt or I Went Walking. 9 A child needs approximately 50 Watch videos of people or objects in action and describe what is happening. words to begin to combine them 9 Pay attention to the use of plurals with an “s”, add them whenever into short phrases. When children possible. Point out words that do not use an “s” to be plural (e.g., men, begin to learn words, they learn that children) to understand placement in space. some words refer to objects, some 9 Play games with “in” and “on.” To focus on correlation with space. -

Development of an Online Tense and Aspect Identifier for English

Development of an online tense and aspect identifier for English John Blake1 Abstract. This article describes the development of a tense and aspect identifier, an online tool designed to help learners of English by harnessing a natural language processing pipeline to automatically classify verb groups into one of 12 grammatical tenses. Currently, there is no website or application that can automatically identify tense in context, and the tense and aspect identifier fills that niche. Learners can use the tool to see how grammatical tenses are used in context. Finite verb groups are automatically identified,and the relevant words in the verb group are highlighted and colorized according to the tense identified. The latest deployed system can identify tenses in simple, compound, and complex sentences. False positive results occur when there is ellipsis of auxiliary verbs or when the tagger assigns the incorrect part-of-speech tag. The user interface of the tense identifier is a web app created using the Flask framework and deployed from the Heroku platform. The tool can be used for inductive and deductive teaching approaches, or even to check for tense consistency in a thesis. Keywords: tense, aspect, iCALL, visualization. 1. Introduction Basic internet searches identify websites that explain the form and function of tenses, and numerous examples of each tense can be found. However, when teachers or learners want to identify the tense and aspect in a particular sentence, no online tool was discovered that could automatically identify the grammatical tense of sentences submitted by users. 1. University of Aizu, Aizuwakamatsu, Japan; [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3150-4995 How to cite: Blake, J. -

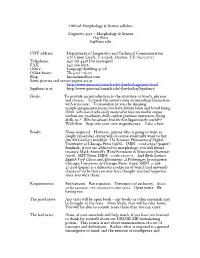

Official! Morphology & Syntax Syllabus

Official Morphology & Syntax syllabus Linguistics 4050 – Morphology & Syntax Haj Ross [email protected] UNT address: Department of Linguistics and Technical Communication 1155 Union Circle, # 305298, Denton, TX 76203-5017 Telephone: 940 565 4458 [for messages] FAX: 940 369 8976 Office: Language Building 407K Office hours: Th 4:00 – 6:00 Blog: haj.nadamelhor.com Some poetics and syntax papers are at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/hajpapers.html Squibnet is at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/haj/Squibnet/ Goals: To provide an introduction to the structure of words, phrases and clauses. To hook the unwary into an unending fascination with structure. To reawaken in you the sleeping morphopragmantactician you have always been and loved being. (Hint: who was it who easily mastered at least one mother tongue without any vocabulary drills, explicit grammar instruction, boring drills, etc.? Who has always been the best linguist in the world??) Well then. Step into your own magnificence. Take a bow. Books: None required. However, anyone who is going to want to deeply remember syntax will of course eventually want to buy Jim McCawley’s indelible The Syntactic Phenomena of English University of Chicago Press (1988). ISBN: 0226556247 (paper). Similarly, if you are addicted to morphology, you will always treasure Mark Aronoff’s Word Formation in Generative Grammar (1976). MIT Press. ISBN: 0-262-51017-0. And Beth Levin’s English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1993) ISBN 0-226- 47533-6 (paper) is a delicious cookie jar of weird (and unweird) classes of verbs that you may have thought you had forgotten since you were three. -

LINGUISTICS 221 Lecture #3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES Part 1. an Utterance Is Composed of a Sequence of Discrete Segments. Is the Segm

LINGUISTICS 221 Lecture #3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES Part 1. An utterance is composed of a sequence of discrete segments. Is the segment indivisible? Is the segment the smallest unit of phonological analysis? If it is, segments ought to differ randomly from one another. Yet this is not true: pt k prs What is the relationship between members of the two groups? p t k - the members of this set have an internal relationship: they are all voiceles stops. p r s - no such relationship exists p b d s bilabial bilabial alveolar alveolar stop stop stop fricative voiceless voiced voiced voiceless SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES! Segments may be viewed as composed of sets of properties rather than indivisible entities. We can show the relationship by listing the properties of each segment. DISTINCTIVE FEATURES • enable us to describe the segments in the world’s languages: all segments in any language can be characterized in some unique combination of features • identifies groups of segments → natural segment classes: they play a role in phonological processes and constraints • distinctive features must be referred to in terms of phonetic -- articulatory or acoustic -- characteristics. 1 Requirements on distinctive feature systems (p. 66): • they must be capable of characterizing natural segment classes • they must be capable of describing all segmental contrasts in all languages • they should be definable in phonetic terms The features fulfill three functions: a. They are capable of describing the segment: a phonetic function b. They serve to differentiate lexical items: a phonological function c. They define natural segment classes: i.e. those segments which as a group undergo similar phonological processes. -

![Arxiv:2106.08037V1 [Cs.CL] 15 Jun 2021 Alternative Ways the World Could Be](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7624/arxiv-2106-08037v1-cs-cl-15-jun-2021-alternative-ways-the-world-could-be-357624.webp)

Arxiv:2106.08037V1 [Cs.CL] 15 Jun 2021 Alternative Ways the World Could Be

The Possible, the Plausible, and the Desirable: Event-Based Modality Detection for Language Processing Valentina Pyatkin∗ Shoval Sadde∗ Aynat Rubinstein Bar Ilan University Bar Ilan University Hebrew University of Jerusalem [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Paul Portner Reut Tsarfaty Georgetown University Bar Ilan University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract (1) a. We presented a paper at ACL’19. Modality is the linguistic ability to describe b. We did not present a paper at ACL’20. events with added information such as how de- sirable, plausible, or feasible they are. Modal- The propositional content p =“present a paper at ity is important for many NLP downstream ACL’X” can be easily verified for sentences (1a)- tasks such as the detection of hedging, uncer- (1b) by looking up the proceedings of the confer- tainty, speculation, and more. Previous studies ence to (dis)prove the existence of the relevant pub- that address modality detection in NLP often p restrict modal expressions to a closed syntac- lication. The same proposition is still referred to tic class, and the modal sense labels are vastly in sentences (2a)–(2d), but now in each one, p is different across different studies, lacking an ac- described from a different perspective: cepted standard. Furthermore, these senses are often analyzed independently of the events that (2) a. We aim to present a paper at ACL’21. they modify. This work builds on the theoreti- b. We want to present a paper at ACL’21. cal foundations of the Georgetown Gradable Modal Expressions (GME) work by Rubin- c. -

Yes, It Is True. While Chinese Sound and Writing Systems Can Be Challenging for Some Learners, Chinese Grammar Is Rarely Deemed Difficult

Grammar I’ve heard that Chinese grammar is relatively easy. Is it true? Yes, it is true. While Chinese sound and writing systems can be challenging for some learners, Chinese grammar is rarely deemed difficult. Chinese is not an inflectional language, meaning it does not distinguish gender, person, tense, case, number, etc. Its sentence structures are mostly straightforward, and many of them overlap with English grammar. For example, the common English structure ‘Subject + Verb + Object’ structure, e.g. I love you, or My dog ate my homework, is also widely used in Chinese. What are some of the unique characteristics of Chinese grammar? Adjectives Are Verbs: Adjectives, or stative verbs, function as verbs, and are usually preceded by an intensifier such as ‘hěn’ (very), or ‘yǒudiǎnr’ (a little). Use of shì,verb ‘to be’,as is required in the English grammar (He is tall), is prohibited. Some examples: Zhōngwén hěn róngyì. (‘Chinese very easy.’) → Chinese is easy. Yīngwén yǒudiǎnr nán. (‘English a little hard.’) → English is a little hard. Note that the intensifier is dropped when a comparison is made: Zhōngwén róngyì. (‘Chinese easy.’) → Chinese is easier. Yīngwén nán. (‘English hard.’) → English is harder. Principle of Temporal sequence: Word order in a Chinese sentence can be very different from that in an English one, where the subject and verb often precede other linguistic units such as prepositions and time word, e.g. ‘I went to New York by train with a friend last weekend.’ A Chinese sentence, on the other hand, follows a temporal sequence principle in which word order is determined based on the relative sequence. -

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience. -

Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4802–4810 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Much Ado About Nothing Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using an NMT Model Andrea Dömötör1;2, Zijian Gyoz˝ o˝ Yang1, Attila Novák1 1MTA-PPKE Hungarian Language Technology Research Group, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology and Bionics Práter u. 50/a, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 2Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Egyetem u. 1, 2087 Piliscsaba, Hungary {surname.firstname}@itk.ppke.hu Abstract The research presented in this paper concerns zero copulas in Hungarian, i.e. the phenomenon that nominal predicates lack an explicit verbal copula in the default present tense 3rd person indicative case. We created a tool based on the state-of-the-art transformer architecture implemented in Marian NMT framework that can identify and mark the location of zero copulas, i.e. the position where an overt copula would appear in the non-default cases. Our primary aim was to support quantitative corpus-based linguistic research by creating a tool that can be used to compile a corpus of significant size containing examples of nominal predicates including the location of the zero copulas. We created the training corpus for our system transforming sentences containing overt copulas into ones containing zero copula labels. However, we first needed to disambiguate occurrences of the massively ambiguous verb van ‘exist/be/have’. We performed this using a rule-base classifier relying on English translations in the English-Hungarian parallel subcorpus of the OpenSubtitles corpus.