Vowel Reduction in Russian Classical Singing: the Case of Unstressed /A/ After Palatalised Consonants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Fall Quarter 2018 (October - December) 1 A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

Pavel Lisitsian Discography by Richard Kummins

Pavel Lisitsian Discography By Richard Kummins e-mail: [email protected] Rev - 17 June 2014 Composer Selection Other artists Date Lang Record # The capital city of the country (Stolitsa Agababov rodin) 1956 Rus 78 USSR 41366 (1956) LP Melodiya 14305/6 (1964) LP Melodiya M10 45467/8 (1984) CD Russian Disc 15022 (1994) MP3 RMG 1637 (2005 - Song Listen, maybe, Op 49 #2 (Paslushai, byt Anthology Vol 1) Arensky mozhet) Andrei Mitnik, piano 1951 Rus MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) 78 USSR 14626 (1947) LP Vocal Record Collector's Armenian (trad) Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1947 Arm Society 1992 Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1948 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) 1960 (San LP New York Records PL 101 Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Maro Ajemian, piano Francisco) Arm (1960) Crane (Groong) 1960 (San LP New York Records PL 101 Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Maro Ajemian, piano Francisco) Arm (1960) Russian Folk Instrument Orchestra - Crane (Groong) Central TV and All-Union Radio LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) - Vladimir Fedoseyev 1968 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) LP DKS 6228 (1955) Armenian (trad) Dogwood forest (Lyut kizil usta tvoi) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1955 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) Dream (Yeraz) (arranged by Aleksandr LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) Dolukhanian) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1948 Arm MP3 RMG -

Tact in Translation Negotiating Trust by the Russian Interpreter, at Home

Tact in Translation Negotiating trust by the Russian interpreter, at home and abroad Eline Helmer University College London Anthropology of Russia and Interpreting Prof Anne White Dr Seth Graham Declaration I, Eline Helmer, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Eline Helmer 2 Abstract Being the only conversational participant with the ability to follow both sides of a cross- linguistic dialogue gives the interpreter the power to obscure or clarify. Because of heightened mutual dependency, all interpreters need trust to perform their roles. They actively build trust, both between self and client and between clients. In academic linguistic contexts, trust is often regarded as based on impartiality: the more objective and invisible the interpreter, the better and more professional he or she will be. In practice, this approach is not always possible, or desirable. The trust relationship between client and interpreter can also be based on closeness and personal interdependence. Interpreting po-chelovecheski (lit. ‘approaching someone in a humane way’) is a colloquial way for Russian interpreters to describe this approach. This thesis explores the negotiation of trust by Russian interpreters. The Russian translation market’s unregulated character, and historical framing of ‘the foreigner’ as someone to be protected and mistrusted, make for an interesting case to study face-to-face interpreting at all levels of the international dialogue. Based on ethnographic fieldwork with interpreters from St Petersburg, Moscow and Pskov, I argue that becoming ‘someone’s voice’ presents a specific caring relationship. -

Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 Is Approved in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

DEVELOPING THE YOUNG DRAMATIC SOPRANO VOICE AGES 15-22 By Monica Ariane Williams Bachelor of Arts – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1993 Master of Music – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2020 Copyright 2021 Monica Ariane Williams All Rights Reserved Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas November 30, 2020 This dissertation prepared by Monica Ariane Williams entitled Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music Alfonse Anderson, DMA. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D. Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Dean Linda Lister, DMA. Examination Committee Member David Weiller, MM. Examination Committee Member Dean Gronemeier, DMA, JD. Examination Committee Member Joe Bynum, MFA. Graduate College Faculty Representative ii ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation provides information on how to develop the young dramatic soprano, specifically through more concentrated focus on the breath. Proper breathing is considered the single most important skill a singer will learn, but its methodology continues to mystify multitudes of singers and voice teachers. Voice professionals often write treatises with a chapter or two devoted to breathing, whose explanations are extremely varied, complex or vague. Young dramatic sopranos, whose voices are unwieldy and take longer to develop are at a particular disadvantage for absorbing a solid vocal technique. First, a description, classification and brief history of the young dramatic soprano is discussed along with a retracing of breath methodologies relevant to the young dramatic soprano’s development. -

Будућност Историје Музике the Future of Music History

Будућност историје музике The Future II/2019 of Music History 27 Реч уреднице Editor's Note ема броја 27 Будућност историје музике инспирисана је истоименим Тсеминаром, организованим у оквиру конференције одржане у Српској History академији наука и уметности септембра 2017. године. Организатор семинара био је Џим Самсон, један од најзначајнијих музиколога данашњице, емеритус професор колеџа Ројал Холовеј Универзитета у Лондону, редовни члан Британске Академије и аутор више од 100 Будућност публикација, међу којима је и прва обухватна историја музике на Балкану на енглеском језику (Music in the Balkans, Leiden: Brill, 2013). Проф. The Future Самсон је љубазно прихватио наш позив да буде гост-уредник овог броја часописа, у којем објављујемо радове четворо од петоро учесника панела историје Будућност историје музике (Рајнхарда Штрома, Мартина Лесера, Кетрин Елис и Марине Фролове-Вокер). Изражавамо велику захвалност овим еминентним музиколозима на исцрпном промишљању будућности музике музике наше дисциплине и настојањима да предмет изучавања постану географске регије, друштвени слојеви и слушалачке праксе који су досад били занемарени у музиколошким разматрањима. he theme of the issue No 27 The Future of Music History was inspired by the Teponymous seminar organised as part of a conference held at the Serbian The Future Academy of Sciences and Arts in September 2017. The seminar was prepared by Jim Samson, one of the most outstanding musicologists of our time, Emeritus Professor of Music, Royal Holloway (University of London), member of Music of the British Academy and author of more than 100 publications, including the first comprehensive history of music in the Balkans in English (Leiden: Brill, Будућност историје 2013). Professor Samson kindly accepted our invitation to be the guest editor History of this issue, in which we publish articles by four of the five panelists (Reinhard Strohm, Martin Loeser, Katharine Ellis and Marina Frolova-Walker). -

KPFA Folio

KPFAFOLIO July 1%9 FM94.1 Ibnfcmt. vacaimt lit KPFA July Folio page 1 acDcfton, «r thcConfcquencct of Qo'^irrrin^ Troops .n h popuroui STt^tr^laTCd Town, taken f ., A KPFA 94.1 FM Listener Supported Radio 2207 Shattuck Avenue Berkeley, California 94704 -mil: Im Tel: (415) 848-6767 ^^^i station Manager Al Silbowitz Administrative Assistant . Marion Timofei Bookkeeper Erna Heims Assistant Bookkeeper .... Mariori Jansen Program Director . Elsa Knight Thompson Promotion Assistant Tom Green i Jean Jean Molyneaux News Director Lincoln Bergman Public Affairs Program Producer Denny Smithson Public Affairs Secretary .... Bobbie Harms Acting Drama & Literature Director Eleanor Sully Children's Programming Director Anne Hedley SKoAfS g«Lt>eHi'o»i Chief Engineer Ned Seagoon [ Engineering Assistants . Hercules Grytpype- thyne, Count Jim Moriarty Senior Production Assistant . Joe Agos . TVt^Hi ttoopj a*c4_ t'-vo-i-to-LS, Production Assistants . Bob Bergstresser Dana Cannon Traffic Clerk Janice Legnitto Subscription Lady Marcia Bartlett »,vJi u/fUyi^elM*^ e«j M"^ K/c> Receptionist Mildred Cheatham FOLIO Secretary Barbara Margolies ^k- »76I i^t^-c«4>v i-'},ooPi M.aAci.«<< The KPFA Folio Pt-lO«tO Hm.lr<^*'rSuLCjCJt4^\f*JL ' ' "a^ cLcC, u>*A C**t". JblooA. July, 1969 Volume20, No. 7 ®1969 Pacifica Foundation All Rights Reserved The KPFA FOLIO is published monthly and is dislributed free as a service to the subscribers of this listener-support- ed station. The FOLIO provides a detailed schedule of J^rx, Ojt-I itl- K«.A^ +Tajy4;^, UCfA programs broadcast A limited edition is published in braille. »J Dates after program listings indicate a repeat broadcast KPFA IS a non-commercial, educational radio station which broadcasts with 59.000 watts at 94 1 MH ly^onday through Fnday Broadcasting begins at 7:00 am, and on V livi tV.t«< weekends and holidays at 8 00 am Programming usually iV AA cUa«.>5 -rtvMUo WeJc. -

The Changing EFL Teacher-Textbook Relationship in Ukraine, 1917 – 2010: a Non-Native English-Speaking Teacher’S Perspective

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2019-01-25 The Changing EFL Teacher-Textbook Relationship in Ukraine, 1917 – 2010: A Non-Native English-Speaking Teacher’s Perspective. An Autoethnography Chebotaryov, Oleksandr Chebotaryov, O. (2019). The Changing EFL Teacher-Textbook Relationship in Ukraine, 1917 – 2010: A Non-Native English-Speaking Teacher’s Perspective. An Autoethnography (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/109860 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Changing EFL Teacher-Textbook Relationship in Ukraine, 1917 – 2010: A Non-Native English-Speaking Teacher’s Perspective An Autoethnography by Oleksandr Chebotaryov A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2019 © Oleksandr Chebotaryov 2019 Abstract The goal of this autoethnographic study is to understand the relationship between a non-native English-speaking teacher of English as a foreign language and their textbooks at different stages of their professional development, in different socio-cultural and political – Soviet and post- Soviet – contexts with the growing tendency of opposing or rejecting textbooks as educational tools. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 111, 1991-1992

OSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA, MUSIC DIRECTOR Boston Symphony Association of Volunteers Opening Night 1991 Gala Committee Co-Chairmen Kathryn W. Bray Goetz B. Eaton Sarah Webb Brown Karen Polvinen Linda H. Clarke Wendy H. Schaedel Thomas B. Corcoran Dorothy M. Stern Deborah B. Davis Barbara Goldsmith Taub Nina L. Doggett Kathy L. Weiss Paul S. Green Jo-Ann Williams Terrence J. Otis Hosts and Hostesses Gayle Archambault Cynthia Gail Lovell Krista Baldini Ann Macdonald Yvonne Bednarz Paula Meridan Emily Belliveau Carol Meyers Linda Billows Denise Mujica Thomas B. Corcoran Martha Pacetti Pamela Duncan Diane Pergola Linda Warch Fenton Pamela Quinlan Nancy Ferguson Elaine Rosenfeld Una and Gustav Fleischmann Barbara Schwartz Jane Florine Bonnie and Paul Schalm Susan Grealis Dorothy Sheldon Peggy Hargrove Diane Siegel Mary-Jane Higgins Virginia Soule Vicki Home Helen Stone Nancy Horton Ann Turley Betty Hosage Thomas Walton Sandra Jenkins Howard Kathy L, Weiss Joan Lauritsen Julianne Whelan Prudy Law Constance White Debra Levin The Opening Night Gala Committee gratefully acknowledges The Boston Company for its continued sponsorship of Opening Night. Our special thanks to these generous donors to Opening Night: Ann Bugatch Bruce Peterson The Catered Affair RIS Paper Company Paul Kroner Design Table Toppers National Film Service Corporation Watson Mailing Service New England Role Playing Society Worcester Envelope Company One Main Street With special thanks to the BSAV Flower/Decorating Committee and the staff and crew of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, especially the Volunteer Office. Benefactors Prof, and Mrs. Rae D. Anderson Deborah B. Davis Mr. and Mrs. David B. Arnold, Jr. Nina L. -

An Introduction to English Phonetics for the Estonian Learner

TARTU STATE UNIVERSITY AN INTRODUCTION TO ENGLISH PHONETICS FOR THE ESTONIAN LEARNER O.MUTT TARTU SSm 19 7 1 TARTU STATE UNIVERSITY Chair of English AN INTRODUCTION TO ENGLISH PHONETICS FO R M ESTONIAN LEARNER O.MUTT'S preface The present survey of English pronunciation is primar ily intended to serve as a handbook for students of English in the Estonian S.S.R. There has been no shortage of good surveys of the pho netic system of British (and more recently of American) Eng lish either abroad or in the Soviet Union. What has been lacking, however, is a more-or-less complete account of the pronunciation of English written from the point of view of the Estonian learner. We do now have a competently written and thorough survey of English intonation and accentuation in comparison with that of Estonian (П. К. Ваараск, Тониче ские средства речи, ч. I—II, Таллин 1964 ), but there is as yet no comprehensive account of the English vowels and con sonants, of various assimilatory phenomena in English, etc. written with the Estonian learner in mind. The present hand book constitutes a modest attempt to fill this gap. The aim of this publication is to provide advanced Estonian learners of English with the essential theoretical and practical material which would enable them to master English pronunciation themselves and to learn how to teach it to others. Chapters 1-2, and the first four sections of Chapter 3» contain material from the course on theoretical » phonetics provided for students of English at universities and institutes in the Soviet Union. -

Tchaikovsky Considered

Tchaikovsky Considered Tracks and clips 1. Introduction 6:10 a. Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il’yich (PT), Piano Concerto No. 2 in G, Op. 44, Gary Graffman, Eugene Ormandy, Philadelphia Orchestra, Columbia MS-6755 recorded 2/17/1965. b. PT, Symphony No. 4 in f, Op. 36, Christoph Eschenbach, Philadelphia Orchestra, Phil. Orch. Priv. Label recorded 3/16/2006.* c. PT, Eugene Onegin, James Levine, Staatskapelle Dresden, Deutsche Grammophon, 0289 423 9592 3 GF 2 released 12/29/1988. ‡ d. PT, Piano Trio in a, Op. 50, Lyubov Timofeyeva, Maxim Fedotov, Kirill Rodin, Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga MK 417001 recorded April, 1990. e. PT, Symphony No. 5 in e, Op. 64, Christoph Eschenbach, Philadelphia Orchestra, Ondine ODE 1076-5 recorded September, 2006. f. Ibid. 2. The Five 20:43 a. Cimarosa, Domenico, Il matrimonio segreto, Daniel Barenboim, English Chamber Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 0289 437 6962 4 GX 3 recorded 1975. ‡ b. Glinka, Mikhail Ivanovich, Nochnoi smotr (The Night Review), Lina Mkrtchyan, Evgeni Talisman, Opus 111 OP30277 released 10/1/2012.◊ c. Dargomïzhsky, Alexander Sergeyevich, The Stone Guest, Andrey Chistiakov, Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra, Brilliant Classics 94028 recorded 1993. d. Balakirev, Alexander Porfir’yevich, Islamey, Julius Katchen Deutsche Grammophon 0289 460 8312 3 DF 2 released 1/12/2004. ‡ e. Cui, César, Préludes, Op. 64, Jeffrey Biegel, Marco-Polo 8.223496 released 11/3/1993.◊ f. Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolay Andreyevich, The Legend of the invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya, Vladimir Fedoseyev, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Koch 3-1144-2-Y5 recorded 7/20/1995. g. Borodin, Alexander Porfir’yevich, String Quartet No. 2 in D, Wister Quartet, Direct-to-Tape released 2008. -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

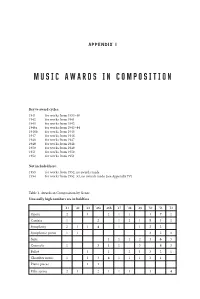

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

Constantine Orbelian, Conductor DE 3517 with Asmik Grigorian, Soprano State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia

Dmitri Hvorostovsky sings of War, Peace, Love and Sorrow Constantine orbelian, conductor DE 3517 with Asmik Grigorian, soprano State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia Helikon Opera Chorus 1 Dmitri Hvorostovsky Sings of War, Peace, Love and Sorrow PROKOFIEV: War and Peace (Scene 1) TCHAIKOVSKY: Mazeppa (Mazeppa’s Aria) Iolanta (Robert’s Aria) • Queen of Spades (Tomsky’s Ballad; Tomsky’s Song) RUBINSTEIN: The Demon (Scene 6) with Asmik Grigorian, soprano Irina Shishkova, mezzo-soprano • Mikhail Guzhov, bass Igor Morozov, tenor • Vadim Volkov, countertenor Constantine Orbelian, conductor Academic State Symphony Orchestra of Russia, “Evgeny Svetlanov” • Helikon Opera Chorus Total Playing Time: 53:51 Dmitri Hvorostovsky Sings of War, Peace, Love and Sorrow 1. Sergei Prokofiev: War and Peace, 4. Tchaikovsky: Queen of Spades, Scene 1 (11:47) Tomsky’s Ballad (5:42) "Svetlaje vesenneje nebo” "Odnazdy v Versale, au jeu de la Reine” (The radiance of the sky in spring) (One day at Versailles, at the Jeu de la Reine) with Asmik Grigorian (Natasha) with Mikhail Guzhov (Surin) and Irina Shishkova (Sonya) and Igor Morozov (Chekalinsky) 2. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Mazeppa, 5. Tchaikovsky: Queen of Spades, Mazeppa’s Aria (5:27) Tomsky’s Song (2:17) "O Mariya, Mariya!” "Yesli b milyye devitzy” (O Maria, Maria!) (If cute girls) 3. Tchaikovsky: Iolanta, Robert’s Aria (2:36) 6. Anton Rubinstein: The Demon, "Kto mozhet sravnitsja s Matildoj moej” Scene 6 (26:03) (Who can compare with my Mathilde) with Asmik Grigorian (Tamara) and Vadim Volkov (Angel) Constantine Orbelian, conductor State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia, “Evgeny Svetlanov” Helikon Opera Chorus Total Playing Time: 53:53 2 ussian is one of the most difficult languag- This studio recording, made in Moscow over es to sing: too many noisy consonants! five consecutive days in October of 2015, brings RNevertheless, some of the most beautiful this plan closer to reality.