Recommended Readings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

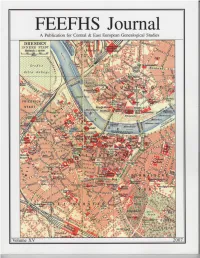

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O. -

4. Widerstand Aus Der Arbeiterbewegung A) Gesamtdarstellungen

4. Widerstand aus der Arbeiterbewegung a) Gesamtdarstellungen Archiv der sozialen Demokratie der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (Hrsg.), Widerstand 1933 - 1945. Sozialdemokraten und Gewerkschafter gegen Hitler. [Katalog zur gleichnamigen Ausstellung], Bonn 1983 (zweite Auflage) Asgodom, Sabine (Hrsg.), "Halt's Maul - sonst kommst nach Dachau!" Männer und Frauen der Arbeiterbewegung berichten über Widerstand und Verfolgung unter dem Nationalsozialismus, Köln 1983 Carsten, Francis L., Widerstand gegen Hitler. Die deutschen Arbeiter und die Nazis, Frankfurt am Main u.a. 1996 Dickhut, Willi, Proletarischer Widerstand gegen Faschismus und Krieg, Düsseldorf 1987 Foitzik, Jan, Zwischen den Fronten. Zur Politik, Organisation und Funktion linker politischer Kleinorganisationen im Widerstand 1933 bis 1939/40, Bonn 1986 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (Hrsg.), Widerstand und Exil der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung 1933 - 1945. Grundlagen und Materialien und Seminarmodelle für die Erwachsenenbildung, Bonn 1981 Gerhard, Dirk, Antifaschisten. Proletarischer Widerstand 1933 – 1945, Berlin 1976 Gittig, Heinz, Illegale antifaschistische Tarnschriften 1933 bis 1945, Frankfurt am Main 1971 Institut für Marxismus-Leninismus beim ZK der SED (Hrsg.), Die Arbeiterbewegung europäischer Länder im Kampf gegen Faschismus und Kriegsgefahr in den zwanziger und dreißiger Jahren. Internationaler Sammelband, Berlin 1981 Jahnke, Karl Heinz, Schwere Jahre. Arbeiterjugend gegen Faschismus und Krieg 1933 – 1945, Essen 1995 Laschitza, Horst/Vietzke, Siegfried, Deutschland und die deutsche Arbeiterbewegung 1933 – 1945. Mit einem Anhang, Berlin 1964 Mason, Timothy W., Arbeiteropposition im nationalsozialistischen Deutschland, in: Peukert, Detlev J. K./Reulecke, Jürgen (Hrsg.), Die Reihen fast geschlossen. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Alltags unterm Nationalsozialismus, Wuppertal 1981, S. 293-313 Mason, Timothy W., Sozialpolitik im Dritten Reich. Arbeiterklasse und Volksgemeinschaft, Opladen 1977 Mommsen, Hans, Der 20. Juli 1944 und die deutsche Arbeiterbewegung, Berlin 1989 (zweite Auflage) Morsch, Günter. -

Vetenskapssocieteten I Lund Årsbok 2017

Vetenskapssocieteten i Lund Årsbok 2017 Vetenskapssocieteten 2017 1.indd 1 2017-06-20 07:15 redaktion Henrik Rahm formgivning Stilbildarna i Mölle, Frederic Täckström tryck Elanders/Fälth & Hässler, Mölnlycke 2017 ISBN 978-91-980551-8-4 ISSN 0349-053x Vetenskapssocieteten 2017 1.indd 2 2017-06-20 07:15 Innehåll Artiklar Frida Blomberg Ordens förhållande till sinnena 5 Sara Gehlin Utbildning för fred 23 Andreas Hallberg Några egenheter i arabisk standardspråksideologi 39 Tobias Hägerland Den sista måltiden som didaktisk tradition och liturgisk formel 49 Kjell Å Modéer Krig, konst och landsförräderi 65 Daniel Möller Gunnar Ekelöf i Grönköping 93 Annika Mörte Alling Från landsbygd till Paris 125 Astrid M. H. Nilsson Ärkebiskop och historiker, känd och ändå okänd 137 Mikael Roll Höra i förtid 153 Elsa Trolle Önnerfors ”Den sista verksamhet, hvartill en qvinna i allmänhet är lämplig” 163 Annika Wallin Om konsten att vara enögd på ett konstruktivt sätt 179 David Willgren Likt en blomsterträdgård 185 Stefan Östersjö Musikalisk transkription 201 Vetenskapssocieteten 2017 1.indd 3 2017-06-20 07:15 Johan Östling Upptäckten av Humboldt 215 Vetenskapssocieteten i Lund Matrikel 225 Stadgar 242 Artikelförfattare 247 Skriftförteckning 252 Vetenskapssocieteten 2017 1.indd 4 2017-06-20 07:15 Frida Blomberg Ordens förhållande till sinnena Inledning Det här kapitlet handlar om ord som har antagits väcka våra sinnen till liv i olika grad – närmare bestämt konkreta ord, abstrakta ord och det som even- tuellt finns däremellan. Perspektivet är neurolingvistiskt, och fokus kommer därför att vara på hur hjärnan bearbetar sinnesupplevelser och ord med olika semantiskt (betydelsemässigt) innehåll. Jag kommer att göra en djupdykning i vad man känner till om konkreta ord och deras relation till framför allt syn- sinnet, men också titta på några aktuella teorier om abstrakta ord och föreslå vägar framåt. -

Download Download

Global histories a student journal From Imperial Science to Post-Patriotism: The Polemics and Ethics of British Imperial History Emma Gattey DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2021.357 Source: Global Histories, Vol. 6, No. 2 (January 2021), pp. 90-101. ISSN: 2366-780X Copyright © 2021 Emma Gattey License URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Publisher information: ‘Global Histories: A Student Journal’ is an open-access bi-annual journal founded in 2015 by students of the M.A. program Global History at Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. ‘Global Histories’ is published by an editorial board of Global History students in association with the Freie Universität Berlin. Freie Universität Berlin Global Histories: A Student Journal Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut Koserstraße 20 14195 Berlin Contact information: For more information, please consult our website www.globalhistories.com or contact the editor at: [email protected]. From Imperial Science to Post-Patriotism: The Polemics and Ethics of British Imperial History by EMMA GATTEY 90 Global Histories: a student journal | VI - 2 - 2020 Emma Gattey | From Imperial Science to Post-Patriotism 91 VI - 2 - 2020 | ABOUT THE AUTHOR History at the University of Oxford. Emma Gattey is a first-year PhD student in History at on Māori activist-intellectuals and their participation in the University of Cambridge. Her current work focuses the University of Cambridge. century. She is a writer and literary critic from Aotearoa century. transnational anticolonial networks in the late twentieth transnational anticolonial networks New Zealand, a former barrister, and has studied law and New Zealand, a former barrister, history at the University of Otago, and Global and Imperial history at the University of Otago, Global Histories: a student journal ABSTRACT Through a brief intellectual biography of British imperial history, upon recent academic and expands this article examines of history. -

Conference Programme

Monday, 6 September 2021 Monday, 6 September 2021 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Please note, that this Programme may be subject to alteration and the organisers reserve the 09:45 – 10:15 Becquerel Prize Ceremony right to do so without giving prior notice. The current version of the Programme is available at www.photovoltaic-conference.com. (i) = invited Chair of Ceremony: Christophe Ballif Monday, 06 September 2021 Chairman of the Becquerel Prize Committee, EPFL, Neuchâtel, Switzerland Becquerel Prize Winner 2021 MONDAY MORNING Ulrike Jahn VDE Renewables, Germany CONFERENCE OPENING Representative of the European Commission: Christian Thiel European Commission Joint Research Centre, Head of Unit, Energy Efficiency and Renewables PLENARY SESSION AP.1 / Scientific Opening Laudatio Thomas Nordmann 8:30 – 09:30 Devices in Evolution: Pushing the Efficiency Limits and TNC Consulting, Switzerland Broadening the Technology Portfolio Chairpersons: 10:30 – 11:15 Opening Addresses Robert P. Kenny European Commission JRC, Ispra, Italy Wim C. Sinke Chaired by: TNO Energy Transition, Petten, The Netherlands João M Serra EU PVSEC Conference General Chair. Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisbon, Portugal AP.1.1 Perfecting Silicon M. Boccard, V. Paratte, L. Antognini, J. Cattin, J. Dréon, D. Fébba, W. Lin, Kadri Simson J. Thomet, D. Türkay & C. Ballif European Commissioner for Energy EPFL, Neuchâtel, Switzerland João M Serra AP.1.2 Beyond Single Junction Efficiencies R. Peibst EU PVSEC Conference General Chair. ISFH, Emmerthal, Germany Faculdade de Ciências -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. -

Zula Druckversion MIT Anhang

Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg Wintersemester 2015/2016 Wissenschaftliche Staatsprüfung für das Lehramt am Gymnasium Wissenschaftliche Arbeit im Fach Geschichte Die sozialdemokratischen Jubiläen 1963 und 2013 Geschichtspolitik im Vergleich Betreut von: Prof. Dr. Dr. Franz-Josef Brüggemeier Historisches Seminar der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Lehrstuhl für Wirtschafts-, Sozial- und Umweltgeschichte Platz der Universität – Kollegiengebäude IV 79085 Freiburg Vorgelegt von: Kilian Flaig geboren am 2. September 1987 Gumpensteige 12, 79104 Freiburg, [email protected] Inhalt Einleitung .................................................................................................................................. 1 1 Theorien, Begriffe, Konzepte .......................................................................................... 4 1.1 Erinnerungskultur und Geschichtspolitik .................................................................... 4 1.2 Ein geschichtspolitischer Blickwinkel ......................................................................... 6 1.3 Vom individuellen zum sozialen Gedächtnis .............................................................. 8 1.4 Vom sozialen zum politischen Gedächtnis ................................................................ 10 1.5 Das Speicher- und Funktionsgedächtnis .................................................................... 11 1.6 Ein Untersuchungsraster für den Vergleich der Jubiläen .......................................... 14 2 Die Geschichtspolitik 1963 ............................................................................................ -

In the Forge of Stalin of Forge the in Kotljarchuk AUS Andrej Gammalsvenskby Is the Only Swedish Settlement to the East from Finland, Founded in 1782

AUS AndrejAUS Kotljarchuk In the Forge of Stalin Gammalsvenskby is the only Swedish settlement to the east from Finland, founded in 1782. In the past of Gammalsvenskby the history of the Soviet Union, Sweden, Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis the international communist movement and Nazi Germany combined in a bizar- Stockholms Studies In History, 100 re form. And even when the ploughmen of the Kherson steppes did not left their native village, the great powers themselves visited them with the intention to rule forever. The history of colony is viewed through the prism of the theory of “forced normalization” and the concept of “changes of collective identity“. The author intends to study the techniques of forced normalization and the strategy of the In the Forge of Stalin collective resistance. Swedish Colonists of Ukraine in Totalitarian Experiments Andrej Kotljarchuk is an associate professor in history, working as a university of the Twentieth Century lecturer at the Department of History, Stockholm University; and as a senior rese- archer at the School of Historical and Contemporary Studies, Södertörn University. His research focuses on ethnic minorities and role of experts’ communities, mass Andrej Kotljarchuk Stockholm 2014 violence and the politics of memory. His recent publications include the book chap- ters “The Nordic Threat: Soviet Ethnic Cleansing on the Kola Peninsula” (2014), “The Memory of Roma Holocaust in Ukraine: Mass Graves, Memory Work and the Politics of Commemoration” (2014); as well as the articles “World War II Memory Politics: Jewish, Polish and Roma Minorities of Belarus”, in Journal of Belarusian Studies (2013) and “Kola Sami in the Stalinist terror: a quantitative analysis”, in Journal of Northern Studies (2012). -

1 TERRAQUEOUS HISTORIES ALISON BASHFORD University Of

TERRAQUEOUS HISTORIES ALISON BASHFORD University of Cambridge Abstract: In her Inaugural Lecture, Alison Bashford, Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, introduces the concept of ‘terraqueous histories’. Maritime historians often stake large claims on world history, and it is indeed the case that the connections and distinctions between land and sea are everywhere in the many traditions of world history-writing. Collapsing the land/sea couplet is useful and ‘terraqueous’ history serves world historians well. The term returns the ‘globe’ to global history, it signals sea as well as land as claimable territory, and in its compound construction foregrounds the history and historiography of meeting places. If the Vere Harmsworth Chair of Imperial and Naval History has recently turned from ‘imperial’ into ‘world’ history, so might its ‘naval’ element become terraqueous history in the twenty-first century. 1 ‘Imperial and naval history’ is an idiosyncratic couplet. Its complex relation to world history charts curious twists and turns in twentieth-century historiography. The first Vere Harmsworth professor, John Holland Rose, presented his inaugural – ‘Naval History and National History’ – on Trafalgar Day, 1919. Well might he do so, since the chair was originally dedicated solely to naval history.1 Prompted by the Royal Empire Society, ‘imperial’ was only added in 1932, and was in place for the election of Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond. And yet Richmond reverted to naval history even more strongly than Holland Rose. Historicising and contextualising his own profession, he presented ‘Naval History and the Citizen’ as his inaugural in 1934.2 Since then, the study of imperial history has dominated the work of successive Vere Harmsworth chairs, with land-history and sea-history receding and advancing, like the tides: E.A. -

The 'Accidental Neuropathologist' – on 40 Years in Neuropathology

Free Neuropathology 1:24 (2020) Harry V. Vinters doi: https://doi.org/10.17879/freeneuropathology-2020-2956 page 1 of 21 Reflections The ’Accidental Neuropathologist' – on 40 Years in Neuropathology Harry V. Vinters1 1 Depts. of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine & Neurology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Ange- les, CA, USA Address for correspondence: Professor Harry V. Vinters · Laboratory Medicine & Pathology · University of Alberta · Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry · Edmonton, Alberta · Canada [email protected] Additional resources and electronic supplementary material: supplementary material Submitted: 14 August 2020 · Accepted: 16 August 2020 · Copyedited by: Christian Thomas · Published: 25 August 2020 Keywords: Neuropathology, UCLA, Personal reflections ciless tyranny that would last until the early 1990s. During that happy time in the early 1990s the USSR thankfully collapsed under the weight of grotesque This article is dedicated to the memory of my corruption and reliable, predictable, frequently brother Raymond John Vinters (1952-2020). comical Soviet incompetence. Members of my family lived in various refugee camps in Europe between 1944 and 1949, at which time they were sponsored by distant relatives to relocate to Cana- da; some of their lasting and most intimate friend- ships were made in the camps during those post- Beginnings in Canada war years. My parents had wed in Lübeck, Germa- ny. My family were Latvians who, by the end of World War II, had become refugees from the Soviet It was their (and my) good fortune that our Union. For the repressive Communist regime that family ended up on the northwest shore of Lake controlled the USSR, my family (on both sides) Superior, in the small city of Port Arthur (now inte- were or would soon become ‘criminals’ who owned grated into a larger municipality, Thunder Bay), land and were involved in commerce. -

Heat of Absorption of CO2 in Aqueous Solutions of DEEA, MAPA and Their Mixture

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Dec 20, 2017 Heat of Absorption of CO2 in Aqueous Solutions of DEEA, MAPA and their Mixture Arshad, Muhammad Waseem; von Solms, Nicolas; Thomsen, Kaj; Svendsen, Hallvard F. Published in: Energy Procedia Link to article, DOI: 10.1016/j.egypro.2013.06.029 Publication date: 2013 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Waseem Arshad, M., von Solms, N., Thomsen, K., & Svendsen, H. F. (2013). Heat of Absorption of CO2 in Aqueous Solutions of DEEA, MAPA and their Mixture. Energy Procedia, 37, 1532-1542. DOI: 10.1016/j.egypro.2013.06.029 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. GHGT- Conference Programme 11th International Conference on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies CCS: Ready to Move Forward 18th - 22nd November 2012 -

St Catharine's College, Cambridge 2015

ST CATHARINE’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE 2015 ST CATHARINE’S MAGAZINE 2015 St Catharine’s College, Cambridge CB2 1RL Published by the St Catharine’s College Society. Porters’ Lodge/switchboard: !"##$ $$% $!! © #!"' The Master and Fellows of St Catharine’s College, Fax: !"##$ $$% $&! Cambridge. College website: www.caths.cam.ac.uk Society website: www.caths.cam.ac.uk/society – Printed in England by Langham Press some details are only accessible to registered members (www.langhampress.co.uk) on (see www.caths.cam.ac.uk/society/register) elemental-chlorine-free paper from Branch activities: www.caths.cam.ac.uk/society/branches sustainable forests. TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial .................................................................................& Society Report Society Committee #!"'–"( .........................................*# College Report The Society President ....................................................*# Master’s report ...................................................................% Report of %*th Annual General Meeting .................*$ The Fellowship.................................................................."& Accounts for the year to $! June #!"' ...................... ** New Fellows ......................................................................"( Society Awards .................................................................*% Retirements and Farewells ...........................................") Society Presidents’ Dinner ............................................*) Professor Sir Christopher