Italian Syntax: a Government-Binding Approach" by L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

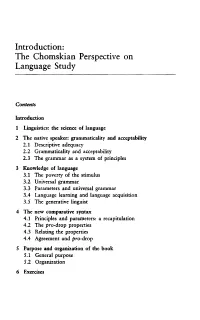

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Curriculum Vitae (Minus Publications)

Curriculum Vitae (minus publications) Donna Jo Napoli Prof. of Linguistics and Social Justice Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA 19081 610-328-8422 (telephone)/ (610) 610-957-6167 (fax) [email protected] http://www.swarthmore.edu/donna-jo-napoli updated 20 September 2021 Education 1973-74 Visiting Scientist in Linguistics (postdoctoral year), MIT. 1973 Ph.D. General and Romance Linguistics (Dept. Romance Lgs & Lits Program A), Harvard University 1971 M.A Italian Literature, Harvard University 1970 A.B. Mathematics. Harvard University Teaching areas syntax, structure of American Sign Language, making bimodal-bilingual video-books to aid in deaf literacy, language matters with respect to Deaf people, linguistic creativity of taboo language, sign language literature from a linguistics perspective, oral and written language, narrative in language compared to dance/theater/ceramics and other arts, field linguistics, morphology, mathematical and linguistic analysis of folk dance, fiction writing workshops (USA and abroad) Employment and Professional Experience since coming to Swarthmore (in fall 1987) 1987–present Swarthmore College, Professor of Linguistics (chair 1987–2002), Professor of Linguistics and Social Justice as of fall 2018 2019 spring CNPQ Visiting Prof. at the University of Santa Caterina in Brazil. 2018 summer Served as Fulbright Specialist at the Universiteit Göttingen in Germany. 2015-16 summers Faculty at New York- St. Petersburg Institute of Linguistics, Cognition and Culture (collaboration of Stony Brook University and St. Petersburg State University in St. Petersburg, Russia) 2015 spr-sum Visiting Professor, Ca’Foscari, University of Venice, Italy; Fulbright Scholar, teaching at Siena School for Liberal Arts, Siena, Italy 2014 October Visiting Scholar to Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil (funded by CNPQ) 2013 fall Creative Writing Program, U. -

Syntax-Semantics Interface

: Syntax-Semantics Interface http://cognet.mit.edu/library/erefs/mitecs/chierchia.html Subscriber : California Digital Library » LOG IN Home Library What's New Departments For Librarians space GO REGISTER Advanced Search The CogNet Library : References Collection : Table of Contents : Syntax-Semantics Interface «« Previous Next »» A commonplace observation about language is that it consists of the systematic association of sound patterns with meaning. SYNTAX studies the structure of well-formed phrases (spelled out as sound sequences); SEMANTICS deals with the way syntactic structures are interpreted. However, how to exactly slice the pie between these two disciplines and how to map one into the other is the subject of controversy. In fact, understanding how syntax and semantics interact (i.e., their interface) constitutes one of the most interesting and central questions in linguistics. Traditionally, phenomena like word order, case marking, agreement, and the like are viewed as part of syntax, whereas things like the meaningfulness of a well-formed string are seen as part of semantics. Thus, for example, "I loves Lee" is ungrammatical because of lack of agreement between the subject and the verb, a phenomenon that pertains to syntax, whereas Chomky's famous "colorless green ideas sleep furiously" is held to be syntactically well-formed but semantically deviant. In fact, there are two aspects of the picture just sketched that one ought to keep apart. The first pertains to data, the second to theoretical explanation. We may be able on pretheoretical grounds to classify some linguistic data (i.e., some native speakers' intuitions) as "syntactic" and others as "semantic." But we cannot determine a priori whether a certain phenomenon is best explained in syntactic or semantics terms. -

Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto De Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic

Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic To cite this version: Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic. Introduction: Complex Adpo- sitions and Complex Nominal Relators. Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Dejan Stosic, Elena Smirnova. Complex Adpositions in European Languages : A Micro-Typological Approach to Com- plex Nominal Relators, 65, De Gruyter Mouton, pp.1-30, 2020, Empirical Approaches to Language Typology, 978-3-11-068664-7. 10.1515/9783110686647-001. halshs-03087872 HAL Id: halshs-03087872 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03087872 Submitted on 24 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova & Dejan Stosic Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard CNRS, ENS & Paris Sorbonne Nouvelle; PSL Lattice laboratory, Ecole Normale Supérieure, 1 rue Maurice Arnoux, 92120 Montrouge, France [email protected] -

On the Linguistic Effects of Articulatory Ease, with a Focus on Sign Languages

Swarthmore College Works Linguistics Faculty Works Linguistics 6-1-2014 On The Linguistic Effects Of Articulatory Ease, With A Focus On Sign Languages Donna Jo Napoli Swarthmore College, [email protected] N. Sanders R. Wright Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-linguistics Part of the Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Donna Jo Napoli, N. Sanders, and R. Wright. (2014). "On The Linguistic Effects Of Articulatory Ease, With A Focus On Sign Languages". Language. Volume 90, Issue 2. 424-456. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-linguistics/39 This work is brought to you for free and open access by . It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2QWKHOLQJXLVWLFHIIHFWVRIDUWLFXODWRU\HDVHZLWKD IRFXVRQVLJQODQJXDJHV Donna Jo Napoli, Nathan Sanders, Rebecca Wright Language, Volume 90, Number 2, June 2014, pp. 424-456 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\/LQJXLVWLF6RFLHW\RI$PHULFD DOI: 10.1353/lan.2014.0026 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lan/summary/v090/90.2.napoli.html Access provided by Swarthmore College (4 Dec 2014 12:18 GMT) ON THE LINGUISTIC EFFECTS OF ARTICULATORY EASE, WITH A FOCUS ON SIGN LANGUAGES Donna Jo Napoli Nathan Sanders Rebecca Wright Swarthmore College Swarthmore College Swarthmore College Spoken language has a well-known drive for ease of articulation, which Kirchner (1998, 2004) analyzes as reduction of the total magnitude of all biomechanical forces involved. We extend Kirchner’s insights from vocal articulation to manual articulation, with a focus on joint usage, and we discuss ways that articulatory ease might be realized in sign languages. -

501 Grammar & Writing Questions 3Rd Edition

501 GRAMMAR AND WRITING QUESTIONS 501 GRAMMAR AND WRITING QUESTIONS 3rd Edition ® NEW YORK Copyright © 2006 LearningExpress, LLC. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by LearningExpress, LLC, New York. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 501 grammar & writing questions.—3rd ed. p. cm. ISBN 1-57685-539-2 1. English language—Grammar—Examinations, questions, etc. 2. English language— Rhetoric—Examinations, questions, etc. 3. Report writing—Examinations, questions, etc. I. Title: 501 grammar and writing questions. II. Title: Five hundred one grammar and writing questions. III. Title: Five hundred and one grammar and writing questions. PE1112.A15 2006 428.2'076—dc22 2005035266 Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Third Edition ISBN 1-57685-539-2 For more information or to place an order, contact LearningExpress at: 55 Broadway 8th Floor New York, NY 10006 Or visit us at: www.learnatest.com Contents INTRODUCTION vii SECTION 1 Mechanics: Capitalization and Punctuation 1 SECTION 2 Sentence Structure 11 SECTION 3 Agreement 29 SECTION 4 Modifiers 43 SECTION 5 Paragraph Development 49 SECTION 6 Essay Questions 95 ANSWERS 103 v Introduction his book—which can be used alone, along with another writing-skills text of your choice, or in com- bination with the LearningExpress publication, Writing Skills Success in 20 Minutes a Day—will give Tyou practice dealing with capitalization, punctuation, basic grammar, sentence structure, organiza- tion, paragraph development, and essay writing. It is designed to be used by individuals working on their own and for teachers or tutors helping students learn or review basic writing skills. -

An Optimality Theoretic Analysis of Rising Changed Tones in Taishanese

An Optimality Theoretic Analysis of Rising Changed Tones in Taishanese Kevin Liang, University of Pennsylvania Taishanese is a member of the Siyi sub-branch of the Yue branch of the Sinitic languages. As described by Taishan Fangyin Zidian (2006), Taishanese has five phonemic tones: three level tones (55, 33, 22) and two falling tones (32, 21). Cheng (1973) describes a so-called “changed tone” process where the tonal contour of the underlying tones can be modified. Depending on the morphological or syntactic context, one of two processes can occur: a level or falling tone becomes a rising tone; or a level tone becomes a falling tone. The present work focuses on the former type of changed tone where a rising tone, which is otherwise not present in Taishanese, can be realized. In the present study, Taishanese tone letter 5 will be represented as H (a tone with the features [+high tone][-low tone][+modify]), tone letter 3 as M (a tone with the features [-high tone][-low tone][-modify]), and tone letter 2 as L (a tone with the features [-high tone][+low tone][+modify]). This is based on the system proposed by Wang (1967) and Woo (1969). Early work on rising changed tones in Taishanese, such as in Cheng (1973), claimed that the process was not phonologically motivated but mostly syntactically and morphologically motivated. Moreover, according to Cheng (1973), only a limited number of words, which are mostly nouns, can undergo this process. However, Him (1980) suggests that the rising changed tone in Taishanese may be the result of an operative process where rises can occur systematically, based on an analysis of related languages. -

Estonian and Latvian Verb Government Comparison

TARTU UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF ESTONIAN AND GENERAL LINGUISTICS DEPARTMENT OF ESTONIAN AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE Miķelis Zeibārts ESTONIAN AND LATVIAN VERB GOVERNMENT COMPARISON Master thesis Supervisor Dr. phil Valts Ernštreits and co-supervisor Mg. phil Ilze Tālberga Tartu 2017 Table of contents Preface ............................................................................................................................... 5 1. Method of research .................................................................................................... 8 2. Description of research sources and theoretical literature ......................................... 9 2.1. Research sources ................................................................................................ 9 2.2. Theoretical literature ........................................................................................ 10 3. Theoretical research background ............................................................................. 12 3.1. Cases in Estonian and Latvian .......................................................................... 12 3.1.1. Estonian noun cases .................................................................................. 12 3.1.2. Latvian noun cases .................................................................................... 13 3.2. The differences and similarities between Estonian and Latvian cases ............. 14 3.2.1. The differences between Estonian and Latvian case systems ................... 14 3.2.2. The similarities -

On Object Shift, Scrambling, and the PIC

On Object Shift, Scrambling, and the PIC Peter Svenonius University of Tromsø and MIT* 1. A Class of Movements The displacements characterized in (1-2) have received a great deal of attention. (Boldface in the gloss here is simply to highlight the alternation.) (1) Scrambling (exx. from Bergsland 1997: 154) a. ... gan nagaan slukax igaaxtakum (Aleut) his.boat out.of seagull.ABS flew ‘... a seagull flew out of his boat’ b. ... quganax hlagan kugan husaqaa rock.ABS his.son on.top.of fell ‘... a rock fell on top of his son’1 (2) Object Shift (OS) a. Hann sendi sem betur fer bréfi ni ur. (Icelandic) he sent as better goes the.letter down2 b. Hann sendi bréfi sem betur fer ni ur. he sent the.letter as better goes down (Both:) ‘He fortunately sent the letter down’ * I am grateful to the University of Tromsø Faculty of Humanities for giving me leave to traipse the globe on the strength of the promise that I would write some papers, and to the MIT Department of Linguistics & Philosophy for welcoming me to breathe in their intellectually stimulating atmosphere. I would especially like to thank Noam Chomsky, Norvin Richards, and Juan Uriagereka for discussing parts of this work with me while it was underway, without implying their endorsement. Thanks also to Kleanthes Grohmann and Ora Matushansky for valuable feedback on earlier drafts, and to Ora Matushansky and Elena Guerzoni for their beneficient editorship. 1 According to Bergsland (pp. 151-153), a subject preceding an adjunct tends to be interpreted as definite (making (1b) unusual), and one following an adjunct tends to be indefinite; this is broadly consistent with the effects of scrambling cross-linguistically.