Railways and the Post Office

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BACKTRACK 22-1 2008:Layout 1 21/11/07 14:14 Page 1

BACKTRACK 22-1 2008:Layout 1 21/11/07 14:14 Page 1 BRITAIN‘S LEADING HISTORICAL RAILWAY JOURNAL VOLUME 22 • NUMBER 1 • JANUARY 2008 • £3.60 IN THIS ISSUE 150 YEARS OF THE SOMERSET & DORSET RAILWAY GWR RAILCARS IN COLOUR THE NORTH CORNWALL LINE THE FURNESS LINE IN COLOUR PENDRAGON BRITISH ENGLISH-ELECTRIC MANUFACTURERS PUBLISHING THE GWR EXPRESS 4-4-0 CLASSES THE COMPREHENSIVE VOICE OF RAILWAY HISTORY BACKTRACK 22-1 2008:Layout 1 21/11/07 15:59 Page 64 THE COMPREHENSIVE VOICE OF RAILWAY HISTORY END OF THE YEAR AT ASHBY JUNCTION A light snowfall lends a crisp feel to this view at Ashby Junction, just north of Nuneaton, on 29th December 1962. Two LMS 4-6-0s, Class 5 No.45058 piloting ‘Jubilee’ No.45592 Indore, whisk the late-running Heysham–London Euston ‘Ulster Express’ past the signal box in a flurry of steam, while 8F 2-8-0 No.48349 waits to bring a freight off the Ashby & Nuneaton line. As the year draws to a close, steam can ponder upon the inexorable march south of the West Coast Main Line electrification. (Tommy Tomalin) PENDRAGON PUBLISHING www.pendragonpublishing.co.uk BACKTRACK 22-1 2008:Layout 1 21/11/07 14:17 Page 4 SOUTHERN GONE WEST A busy scene at Halwill Junction on 31st August 1964. BR Class 4 4-6-0 No.75022 is approaching with the 8.48am from Padstow, THE NORTH CORNWALL while Class 4 2-6-4T No.80037 waits to shape of the ancient Bodmin & Wadebridge proceed with the 10.00 Okehampton–Padstow. -

The King's Post, Being a Volume of Historical Facts Relating to the Posts, Mail Coaches, Coach Roads, and Railway Mail Servi

Lri/U THE KING'S POST. [Frontispiece. THE RIGHT HON. LORD STANLEY, K.C.V.O., C.B., M.P. (Postmaster- General.) The King's Post Being a volume of historical facts relating to the Posts, Mail Coaches, Coach Roads, and Railway Mail Services of and connected with the Ancient City of Bristol from 1580 to the present time. BY R. C. TOMBS, I.S.O. Ex- Controller of the London Posted Service, and late Surveyor-Postmaster of Bristol; " " " Author of The Ixmdon Postal Service of To-day Visitors' Handbook to General Post Office, London" "The Bristol Royal Mail." Bristol W. C. HEMMONS, PUBLISHER, ST. STEPHEN STREET. 1905 2nd Edit., 1906. Entered Stationers' Hall. 854803 HE TO THE RIGHT HON. LORD STANLEY, K.C.V.O., C.B., M.P., HIS MAJESTY'S POSTMASTER-GENERAL, THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED AS A TESTIMONY OF HIGH APPRECIATION OF HIS DEVOTION TO THE PUBLIC SERVICE AT HOME AND ABROAD, BY HIS FAITHFUL SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. PREFACE. " TTTHEN in 1899 I published the Bristol Royal Mail," I scarcely supposed that it would be practicable to gather further historical facts of local interest sufficient to admit of the com- pilation of a companion book to that work. Such, however, has been the case, and much additional information has been procured as regards the Mail Services of the District. Perhaps, after all, that is not surprising as Bristol is a very ancient city, and was once the second place of importance in the kingdom, with necessary constant mail communication with London, the seat of Government. I am, therefore, enabled to introduce to notice " The King's Post," with the hope that it will vii: viii. -

The Royal Mail

THE EO YAL MAIL ITS CURIOSITIES AND ROMANCE SUPERINTENDENT IN THE GENERAL POST-OFFICE, EDINBURGH SECOND EDITION WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXXXV All Rights reserved NOTE. It is of melancholy interest that Mr Fawcett's death occurred within a month from the date on which he accepted the following Dedication, and before the issue of the Work. TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE HENEY FAWCETT, M. P. HER MAJESTY'S POSTMASTER-GENERAL, THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE, BY PERMISSION, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. PEEFACE TO SECOND EDITION. favour with which 'The Eoyal Mail' has THEbeen received by the public, as evinced by the rapid sale of the first issue, has induced the Author to arrange for the publication of a second edition. edition revised This has been and slightly enlarged ; the new matter consisting of two additional illus- " trations, contributions to the chapters on Mail " " Packets," How Letters are Lost," and Singular Coincidences," and a fresh chapter on the subject of Postmasters. The Author ventures to hope that the generous appreciation which has been accorded to the first edition may be extended to the work in its revised form. EDINBURGH, June 1885. INTRODUCTION. all institutions of modern times, there is, - OF perhaps, none so pre eminently a people's institution as is the Post-office. Not only does it carry letters and newspapers everywhere, both within and without the kingdom, but it is the transmitter of messages by telegraph, a vast banker for the savings of the working classes, an insurer of lives, a carrier of parcels, and a distributor of various kinds of Government licences. -

Her Majesty's Mails

HER MAJESTY'S MAILS: HISTOEY OF THE POST-OFFICE, AND AN INDUSTRIAL ACCOUNT OF ITS PRESENT CONDITION. BY WJLLIAM LEWINS, OF THE GENEKAL POST-OFFICE. SECOND EDITION, REVISED, CORRECTED, AND ENLARGED. LONDON : SAMPSON LOW, SON, AND MAESTON, MILTON HOUSE, LUDGATE HILL. 1865. [The Right of Translation is reserved.} TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE HENRY, LOED BKOUGHAM AND VAUX ETC. ETC. ETC. WHO DURING AN UNUSUALLY LONG AND LABORIOUS LIFE HAS EVER BEEN THE EARNEST ELOQUENT AND SUCCESSFUL ADVOCATE OF ALL KINDS OF SOCIAL PROGRESS AND INTELLECTUAL ADVANCEMENT AND WHO FROM THE FIRST GAVE HIS MOST STRENUOUS AND INVALUABLE ASSISTANCE IN PARLIAMENT TOWARDS CARRYING THE MEASURE OF PENNY POSTAGE REFORM IS BY PERMISSION DEDICATED WITH FEELINGS OF DEEP ADMIRATION RESPECT AND GRATITUDE BY THE AUTHOR PBEFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. THE general interest taken in this work on its first appearance, and the favourable reception accorded to it, has abundantly- proved that many agreed with me in thinking that, in spite of the world of books issuing from the press, there were still great gaps in the "literature of social history," and that to some extent my present venture was calculated to fill one of them. That my critics have been most indulgent I have had more and more reason to know as I have gone on with the revision of the book. To make it less unworthy of the kind treatment it received, I have taken this opportunity to re-write the principal part of it, and to go over with extreme care and fidelity the remaining portion. In addition to the ordinary sources of information, of which I have made diligent and conscientious use, I have been privileged to peruse the old records of the Post-office, still carefully kept at St. -

! I9mnm 11M Illulm Ummllm Glpe-PUNE-005404 I the POST OFFICE the WHITEHALL SERIES Editld Hy Sill JAME

hlllllljayarao GadgillibraJ)' ! I9mnm 11m IllUlm ummllm GlPE-PUNE-005404 I THE POST OFFICE THE WHITEHALL SERIES Editld hy Sill JAME. MARCHANT, 1.1.1., 1.L.D:- THE HOME OFFICE. By Sir Edward Troup, II.C.B., II.C.".O. Perma",,'" UtuUr-S_.uuy 01 SIIJU ill tJu H~ 0ffiu. 1908·1922. MINISTRY OF HEALTH. By Sir Arthur Newsholme. II.C.B. ".D., PoIl.C.P.. PriMpiM MId;';; OjJiur LoetII Goo_"'" B04Id £"gla"d ..... WiMeI 1908.1919, ","g'" ill 1M .Mi"isI" 01 H..ult. THE INDIA OFFICE. By Sir Malcolm C. C. Seton, II.C.B. Dep..,)! Undn·S,erela" 01 SIal. ,;"u 1924- THE DOMINIONS AND COLONIAL OFFICES. By Sir George V. Fiddes, G.c.... G •• K.C.B. P_'" Undn-SeC1'eIA" 01 Sial. lor 1M Cokmitl. Igl().lg2l. THE POST OFFICE. By Sir Evelyn Murray, II.C.B. S_.uuy 10 1M POll Offiu.mu 1914. THE BOARD OF EDUCATION. B1 Sir Lewis Amherst Selby Blgge, BT•• II.C.B. PermaffMII S_,. III" BOMd 0/ £duUlliotlI9u-lg2,. THE POST OFFICE By SIR EVELYN MURRAY, K.C.B. Stt",ary to tht POI' Offict LONDON ~ NEW YORK G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS LTD. F7 MIIIk ""J P,.;"I,J", G,.,tli Bril";,, till. &Mpll Prinl;,,: WtIf'tt. GtII, SIf'tI'. Km~. w.e., PREFACE No Department of State touches the everyday life of the nation more closely than the Post Office. Most of us use it daily, but apart from those engaged in its administration there are relatively few who have any detailed knowledge of the problems with which it has to deal, or the machinery by which it is catried on. -

Locomotives of 1907-C.LAKE-1907-Pg 56.Pdf

F CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ^N. QJ/^\D F CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF Ji^ i J>w>mf<^cM'^^ i F CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ~ 1" QJSV> LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IIRRtRY OF THF IINIVFRSiTY (IF RtLIFORNIt LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOCOMOTIVES OF 1907 BY CHAS. S. J.AKE, A.M.I.MECH.E., MEMBER SOCIETY OF ARTS. " " Author of The World's Locomotives," The Locomotive Simply Explained" "Locomotives of 1906." LONDON : PERCIVAL MARSHALL & CO., 26-29, POFFIN'S COURT, FLEET STREET, E.G. FOUR-CYLINDER SIMPLE (460 TYPE) EXPRESS LOCOMOTIVE, GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY. MR. G. J. CHURCHWARD, M.Inst.C.E., Locomotive Superintendent, SWINDON. Leading Particulars. : ins. 26 ins. ft. Cylinders (4) Diameter, 14^ ; piston stroke, Grate area, 27-07 sq. wheels ft. 2 ins. Bogie diameter. 3 Working pressure, 225 Ibs. per sq. in. wheels diameter, 6 ft. 8J ins. tons 16 cwts. of Coupled Weight on coupled wheels, 58 ; weight engine (in : ft. ft. Wheelbase 14 9 ins. ; total, 3 ins. Rigid, 27 working order), 76 tons 14 cwts. : at ft. ins. ft. 6 ins. -

Honorary President Professor Dugald Cameron OBE

Honorary President Professor Dugald Cameron OBE PACIFIC PROGRESS (photo courtesy www.colourrail.com) We haven’t seen much snow in Surrey in recent years but you can almost feel the chill in this fine view of Merchant Navy No 35005 ‘Canadian Pacific’ approaching Pirbright Junction in the winter of 1963. As mentioned previously in these pages, ‘Can Pac’ was one of 10 Merchant Navy Pacifics to be fitted with North British boilers from new and the loco still carries it in preservation today. At the present time No 35005 is undergoing a thorough overhaul with the NBL boiler at Ropley on the Mid Hants Railway and the frames etc at Eastleigh Works in Hampshire. Mid Hants volunteer John Barrowdale was at Ropley on 15th January and reports that CP’s new inner firebox was having some weld grinding attention before some new weld is added. The boilersmith told him that apart from the welding on the inner wrapper plus a bit on the outer wrapper it is virtually complete with the thermic synthons all fitted in. They hope to be able to drop the inner wrapper into the outer wrapper by the end of March and then the long task of fitting all the 2400 odd stays into the structure beckons plus the fitting of the foundation ring underneath. After work on the boiler is complete it will be sent to Eastleigh to be reunited with the frames and final assembly can begin. There is a long way to go but it shows what can be achieved by a dedicated team of preservationists ! We wish John and his colleagues the very best of luck and look forward to seeing Canadian Pacific in steam again in the years to come. -

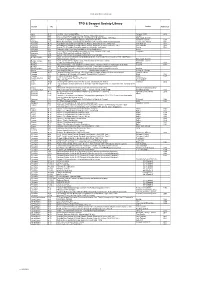

Revised & Renumbered List 17.11.2015V2.Xlsx

TPO Seapost Society Library List TPO & Seapost Society Library Country Ref Title Author Published . Aden M 75 Bombay - Aden Seapost Office Dovey & Bottrill 2012 Africa M25 No 11 Cockrill series Woerman Line, History, Ships and Cancels Cockrill Africa M30 No 41 Cockrill series Mailboat Service from Europe to Belgian Congo, 1879-1922 Güdenkauf, Cockrill Africa R 52 The TPOs of Imperial Military Railways (Anglo-Boer War PS) Griffiths & Drysdall, 1997 Argentina R 46 Matasellos Utilizados en las Estafetas Ambulantes Ferroviarias 1865-1892 (in Spanish) Ceriani & Kneitschel 1987 Australia M 70 Australia,New Zealand UK Mails Rates & Routes ;Ships Out & Home 1880. Vol 1 Colin Tabeart 2011 Australia M 70 Australia,New Zealand UK Mails Rates & Routes ;Ships Out & Home 1881-1900. Vol 2 Colin Tabeart 2011 Australia R 11 Victoria: The Travelling Post Offices and their Markings, 1865-1912 Purves 1955 Australia R 12 Postmarks of the Travelling Post Offices of New South Wales Dovey Australia R 53 The TPOs of South Australia (Donated by the Stuart Rossiter Trust Fund) Presgrave Australia R 87 Victoria, TPOs and their markings, 1865-1912 Austria R 25 German TPO cancels in occupied Austria 1938-1945 and after. Belgian Congo M32 No 43 Cockrill series Belgian Congo Mailboat Steamers on Congo Rivers & Lakes, 1896-1940 Postal History and Cancellations Gudenkauf, Cockrill Belgian CongoM33No 44 Cockrill series Belgian Congo. Postal History of the Lado Enclave Gudenkauf, Cockrill Belgium R 19 Les Bureaux Ambulants de Belgique D'Hondt 1936 Belgium R 20 Atlas Chronologique et Description des Obliterations et Marques Postales ''Ambulants'' de Belgique Creuven 1949 Belgium R 69 Les Bureaux Ambulants De Belgique. -

Post Office Numbers

POST OFFICE NUMBERS NUMERALS USED IN POST OFFICES IN ENGLAND WALES AND USED ABROAD 1844 TO 1969. AND THE STATUS OF OFFICES WITH NUMERAL CANCELLATIONS 1844 TO 1906. JOHN PARMENTER AND KEN SMITH. First published in 2003 by John Parmenter, 23 Jeffreys Road, London SW4 6QU. © John Parmenter and Ken Smith 2003. ISBN 0 9511395 6 8 Printed and published by John Parmenter, 23 Jeffreys Road, London SW4 6QU. CONTENTS A….INTRODUCTION B….ALL OFFICES IN NUMERICAL ORDER C….ALL OFFICES IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER D….ALL OFFICES IN COUNTY ORDER:- ENGLAND AND WALES USED ABROAD MAILBOATS RAILWAY STATION OFFICES RAILWAY TPO’S E….RAILWAY SUB OFFICES THAT USED BARRED NUMERAL CANCELS F….NUMERAL ERRORS G…LONDON OFFICES IN NUMERICAL ORDER H…LONDON OFFICES IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER I…LONDON OFFICES BY COUNTY, THEN ALPHABETICAL ORDER J…LONDON OFFICES BY DISTRICT, THEN ALPHABETICAL ORDER This book contains two parts: 1/ A list of all the numeral allocations to Post Offices in the official lists of England, Wales and Used Abroad. Much of this information has previously been available but in separate publications. Brumell stopped in 1906, which was the last official list available when numeral cancellations were still in widespread use. However the allocation of new numerals continued until 1967. 2/ A list of the status of each office that was allocated a numeral cancellation, for the period 1844 to 1906. This can explain where outgoing mail from an office was cancelled. Of particular interest is the use of barred numeral cancellations of a superior office on mail from a subordinate office during a period when the latter had a number allocated to it. -

Narrow Cab/Splashers) LOCOMOTIVE KIT

Brassmasters Scale Models www.brassmasters.co.uk L&SWR/SOUTHERN RAILWAY DRUMMOND T9 4-4-0 (narrow cab/splashers) LOCOMOTIVE KIT Designed by Martin Finney 4MM SCALE OO - EM - P4 INSTRUCTIONS AND PROTOTYPE NOTES PO Box 1137 Sutton Coldfield B76 1FU Copyright Brassmasters 2017 SECTION 1: BRIEF HISTORICAL DETAILS The locomotives which form the subject of this kit are the original ‘narrow’ series of Dugald Drummond’s celebrated T9 4-4-0s for the LSWR. A total of 51 locomotives were built by Dubs & Co. and at Nine Elms Works under five Order Numbers as follows: Numbers Date Built Maker Works/ Order Number Firebox Water Tubes 702 - 719 2/1899 - 6/1899 Dubs & Co. 3746-3763 Yes 721 - 732 6/1899 - 1/1900 Dubs & Co. 3764-3775 Yes 773# 12/1901 Dubs & Co. 4038 Yes 113 - 122 6/1899 - 9/1899 Nine Elms G9 No 280 - 284 10/1899 - 11/1899 Nine Elms K9 No 285 - 289 1/1900 - 2/1900 Nine Elms O9 No # renumbered 733 12/1924 For a detailed history of this class I suggest you refer to the following definitive books by the late D.L.Bradley: Part two of 'The Locomotives of the L.S.W.R.’ published by the R.C.T.S. LSWR Locomotives - The Drummond Classes published by Wild Swan. Other valuable sources of information and photographs are: The Drummond Greyhounds of the LSWR - D.L.Bradley - David & Charles A Pictorial Record of Southern Locomotives - J.H.Russell - OPC Drummond Locomotives - Brian Haresnape & Peter Rowledge - Ian Allan Locomotives Illustrated No. 44 - The Drummond 4-4-0s and Double singles of the LSWR - Ian Allan Southern Steam Locomotive Survey - The Drummond Classes - Bradford Barton www.rail-online.co.uk – lots of prototype photographs Variations/Modifications incorporated into the kit Starting with numbers 702,709 & 724 in May 1923 the locomotives were extensively rebuilt involving new: Smokeboxes: new, larger, smokeboxes were fitted incorporating the ‘Eastleigh’ superheater. -

The Royal Mail

- и Г s f-a M S ' п з $ r THE HOYAL MAIL í THE E 0 Y A L MAIL ITS CURIOSITIES AND ROMANCE BY JAMES WILSON HYDE SUPERINTENDENT IN THE GENERAL POST-OKKICK, EDINBURGH THIRD EDITION LONDON SIMPKIN, MARSHALL AND CO. MDCCCLXXXIX. A ll Eights reserved. N ote. —It is of melancholy interest that Mr Fawcett’s death occurred within a month from the date on which he accepted the following Dedication, and before the issue of the Work. \ то THE RIGHT HONOURABLE HENRY FAWCETT, M. P. h e r m a je s t y 's po stm a ste r -g e n e r a l , THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE, BY PERMISSION, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION. ГПНЕ second edition of ‘ The Royal Mail ’ having been sold out some eighteen months ago, and being still in demand, the Author has arranged for the publication of a further edition. Some additional particulars of an interest ing kind have been incorporated in the work; and these, together with a number of fresh illustrations, should render ‘ The Royal Mail ’ still more attractive than hitherto. The modem statistics have not been brought down to date; and it will be understood that these, and other matters (such as the circulation of letters), which are sub ject to change, remain in the work as set forth in the first edition. E d in b u r g h , Febrtuiry 1889. PREFACE TÔ SECOND EDITION. ГГШЕ favour with which ‘ The Royal Mail’ has been received by the public, as evinced by the rapid sale of the first issue, has induced the Author to arrange for the publication of a second edition. -

Railways: Royal Mail Services, 2003

Railways: Royal Mail services, 2003- Standard Note: SN/BT/2251 Last updated: 13 April 2010 Author: Louise Butcher Section Business and Transport On 6 June 2003 the Royal Mail announced that it was going to withdraw its entire rail network of services for mail distribution by March 2004, in favour of a road-based distribution network. The Government’s view was that the carriage of mail by rail was a commercial issue between the Royal Mail and its contractors and that they were essentially two private companies that were involved in commercial negotiations. In January 2004, Royal Mail ran what was then thought to be its last Travelling Post Office, supposedly ending 166 years of service. Less than six months later the company announced that it was in talks to re-establish some kind of rail distribution and delivery service and was negotiating with GB Railfreight. Services were revived on a trial basis at the end of 2004 and in May 2005 Royal Mail signed a contract with GB Railfreight for a least two nightly rail services between London and Scotland until March 2006, this was subsequently extended to 2007 and then to 2010. Information on other rail issues can be found on the Railways topical page of the Parliament website. Contents 1 The end of Royal Mail’s rail contract, 2003-04 2 1.1 Royal Mail’s decision, impact on freight and view of the Government 2 1.2 Opposition to the end of services 5 2 Return of mail services, 2004- 6 This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual.