Her Majesty's Mails

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography of A.F. Pollard's Writings

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF A.F. POLLARD'S WRITINGS This bibliography is not quite complete: we omitted mention of very short book reviews, and we have not been able to trace every one of Pollard's contributions to the T.L.S. As to his letters to the Editor of The Times, we only mentioned the ones consulted on behalf of our research. There has been no separate mention of Pollard's essays from the years 1915-1917, collectedly published in The Commonwealth at War (1917). The Jesuits in Poland, Oxford, 1892. D.N.B. vol. 34: Lucas, Ch. (1769-1854); Luckombe, Ph. (d. 1803); Lydiat, Th. (1572-1646). vol. 35: Macdonald, A. (1834-1886); Macdonell, A. (1762-1840); Macegan, O. (d. 1603); Macfarlan, W. (d. 1767); Macha do, R. (d. lSI I?); Mackenzie, W.B. (1806-1870); Maclean, Ch. (1788-1824); Magauran, E. (IS48-IS93); Maguire, H. (d. 1600); Maguire, N. (1460-1512). vol. 36: Manderstown, W. (ISIS-IS40); Mansell, F. (1579-166S); Marshall, W. (d. 153S); Martin, Fr. (1652-1722); Martyn, R. (d. 1483); Mascall,R. (d. 1416); Mason,]. (1503-1566); Mason, R. (1571-1635). Review :].B. Perkins, France under the Regency, London, 1892. E.H.R. 8 (1893), pp. 79 1-793. 'Sir Edward Kelley' in Lives oj Twelve Bad Men, ed. Th. Seccombe, London, 1894, pp. 34-54· BIBLIOGRAPHY OF A.F. POLLARD'S WRITINGS 375 D.N.B. vol. 37: Matcham, G. (1753-1833); Maunsfield, H. (d. 1328); Maurice, Th. (1754-1824); Maxfield, Th. (d. 1616); May, W. (d. 1560); Mayart, S. (d. 1660?); Mayers, W.F. -

The King's Post, Being a Volume of Historical Facts Relating to the Posts, Mail Coaches, Coach Roads, and Railway Mail Servi

Lri/U THE KING'S POST. [Frontispiece. THE RIGHT HON. LORD STANLEY, K.C.V.O., C.B., M.P. (Postmaster- General.) The King's Post Being a volume of historical facts relating to the Posts, Mail Coaches, Coach Roads, and Railway Mail Services of and connected with the Ancient City of Bristol from 1580 to the present time. BY R. C. TOMBS, I.S.O. Ex- Controller of the London Posted Service, and late Surveyor-Postmaster of Bristol; " " " Author of The Ixmdon Postal Service of To-day Visitors' Handbook to General Post Office, London" "The Bristol Royal Mail." Bristol W. C. HEMMONS, PUBLISHER, ST. STEPHEN STREET. 1905 2nd Edit., 1906. Entered Stationers' Hall. 854803 HE TO THE RIGHT HON. LORD STANLEY, K.C.V.O., C.B., M.P., HIS MAJESTY'S POSTMASTER-GENERAL, THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED AS A TESTIMONY OF HIGH APPRECIATION OF HIS DEVOTION TO THE PUBLIC SERVICE AT HOME AND ABROAD, BY HIS FAITHFUL SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. PREFACE. " TTTHEN in 1899 I published the Bristol Royal Mail," I scarcely supposed that it would be practicable to gather further historical facts of local interest sufficient to admit of the com- pilation of a companion book to that work. Such, however, has been the case, and much additional information has been procured as regards the Mail Services of the District. Perhaps, after all, that is not surprising as Bristol is a very ancient city, and was once the second place of importance in the kingdom, with necessary constant mail communication with London, the seat of Government. I am, therefore, enabled to introduce to notice " The King's Post," with the hope that it will vii: viii. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

The Role of the Channel Islands in the Development and Application of Norman Law During the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Period

THE JERSEY & GUERNSEY LAW REVIEW 2018 THE ROLE OF THE CHANNEL ISLANDS IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND APPLICATION OF NORMAN LAW DURING THE LATE MIDDLE AGES AND EARLY MODERN PERIOD Tim Thornton Although attention has been paid to the impact of continental Norman law on the Channel Islands, the impact of the experience and practice of the islands themselves on Norman law, more generally, has not been taken into consideration. This is despite the fact that it is increasingly clear that, far from being isolated from developments in continental Normandy, at the social, economic and ecclesiastical level after 1204 the islands were directly involved in exchanges in many contexts. In this paper the role of the islands is assessed in the practice and development of Norman law in the period from the fifteenth century to the seventeenth century. 1 In this short paper I intend to consider briefly the history of Norman law in its relation to the Islands, and more specifically the place and influence of the Islands within the wider Norman legal context. The role of Norman customary law in Jersey and Guernsey has been extensively discussed. Terrien’s commentary on the Ancienne Coutume was published in 1574 and was reprinted in 1578 and 1654. It was in Guernsey’s case the reference point for the limited degree of codification achieved through the Approbation des Loix in 1583, while Jersey remained more straightforwardly able to refer to what ironically in same year was published on the mainland as the Coutume Reformée. Even after the end of the 16th century, Island law across both Bailiwicks continued to develop with reference to the practice of the mainland, including the Coutume Reformée, through the commentators on it, Basnage, Bérault, Godefroy, and D’Aviron being the main ones in the period before the 18th century. -

The Royal Mail

THE EO YAL MAIL ITS CURIOSITIES AND ROMANCE SUPERINTENDENT IN THE GENERAL POST-OFFICE, EDINBURGH SECOND EDITION WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXXXV All Rights reserved NOTE. It is of melancholy interest that Mr Fawcett's death occurred within a month from the date on which he accepted the following Dedication, and before the issue of the Work. TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE HENEY FAWCETT, M. P. HER MAJESTY'S POSTMASTER-GENERAL, THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE, BY PERMISSION, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. PEEFACE TO SECOND EDITION. favour with which 'The Eoyal Mail' has THEbeen received by the public, as evinced by the rapid sale of the first issue, has induced the Author to arrange for the publication of a second edition. edition revised This has been and slightly enlarged ; the new matter consisting of two additional illus- " trations, contributions to the chapters on Mail " " Packets," How Letters are Lost," and Singular Coincidences," and a fresh chapter on the subject of Postmasters. The Author ventures to hope that the generous appreciation which has been accorded to the first edition may be extended to the work in its revised form. EDINBURGH, June 1885. INTRODUCTION. all institutions of modern times, there is, - OF perhaps, none so pre eminently a people's institution as is the Post-office. Not only does it carry letters and newspapers everywhere, both within and without the kingdom, but it is the transmitter of messages by telegraph, a vast banker for the savings of the working classes, an insurer of lives, a carrier of parcels, and a distributor of various kinds of Government licences. -

! I9mnm 11M Illulm Ummllm Glpe-PUNE-005404 I the POST OFFICE the WHITEHALL SERIES Editld Hy Sill JAME

hlllllljayarao GadgillibraJ)' ! I9mnm 11m IllUlm ummllm GlPE-PUNE-005404 I THE POST OFFICE THE WHITEHALL SERIES Editld hy Sill JAME. MARCHANT, 1.1.1., 1.L.D:- THE HOME OFFICE. By Sir Edward Troup, II.C.B., II.C.".O. Perma",,'" UtuUr-S_.uuy 01 SIIJU ill tJu H~ 0ffiu. 1908·1922. MINISTRY OF HEALTH. By Sir Arthur Newsholme. II.C.B. ".D., PoIl.C.P.. PriMpiM MId;';; OjJiur LoetII Goo_"'" B04Id £"gla"d ..... WiMeI 1908.1919, ","g'" ill 1M .Mi"isI" 01 H..ult. THE INDIA OFFICE. By Sir Malcolm C. C. Seton, II.C.B. Dep..,)! Undn·S,erela" 01 SIal. ,;"u 1924- THE DOMINIONS AND COLONIAL OFFICES. By Sir George V. Fiddes, G.c.... G •• K.C.B. P_'" Undn-SeC1'eIA" 01 Sial. lor 1M Cokmitl. Igl().lg2l. THE POST OFFICE. By Sir Evelyn Murray, II.C.B. S_.uuy 10 1M POll Offiu.mu 1914. THE BOARD OF EDUCATION. B1 Sir Lewis Amherst Selby Blgge, BT•• II.C.B. PermaffMII S_,. III" BOMd 0/ £duUlliotlI9u-lg2,. THE POST OFFICE By SIR EVELYN MURRAY, K.C.B. Stt",ary to tht POI' Offict LONDON ~ NEW YORK G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS LTD. F7 MIIIk ""J P,.;"I,J", G,.,tli Bril";,, till. &Mpll Prinl;,,: WtIf'tt. GtII, SIf'tI'. Km~. w.e., PREFACE No Department of State touches the everyday life of the nation more closely than the Post Office. Most of us use it daily, but apart from those engaged in its administration there are relatively few who have any detailed knowledge of the problems with which it has to deal, or the machinery by which it is catried on. -

The General Court of Virginia, 1619–1776

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2020 The General Court of Virginia, 1619–1776 William Hamilton Bryson University of Richmond - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation W. H. Bryson, The General Court of Virginia 1619-1776, in Central Courts in Early Modern Europe and the Americas, 531 (A. M. Godfrey and C. H. van Rhee ed., 2020). This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 29.04.20, 15:24 | L101 |Werk Godfrey_van Rhee, Duncker | #13501, Godfrey_van Rhee.indd, D / VSchn | ((NR / Fr/CS6)) S. 530 W. H. BRySoN The General Court of Virginia, 1619–1776 Introduction The General Court of Virginia began with the reorganization of the gov- ernment of the colony of Virginia in 1619. The court was established not for any political motives to control, or for any financial motives to collect lucra- tive fines, but it was a part of the tradition of good government. Private disputes are better settled in official courts of law rather than by self-help and vendetta. Therefore, access to the courts is good public policy. From its foundation in 1607 until 1624, Virginia was a private corporation that was created by a succession of royal charters; in its organization, it was similar to an English municipal corporation.1 The first royal charter and the accompanying instructions set up a Council of government, and this Council was given broad and general judicial powers.2 The model for this was the cities and boroughs of medieval England which had their own courts of law for the settlement of local disputes. -

The Library Catalogue Is Available As a PDF Here

Author Title Section Name Shelf Index Scriptorum Novus. Mediae Latinitatis Ab Anno DCCC Usque AD Dictionaries 2E Annum MCC. Supplementum Rolls of Parliament, Reign of Henry V, vol.IV Irish Sources: Oversize 4A Rolls of Parliament, Reign of Henry VI, vol.V Irish Sources: Oversize 4A Rolls of Parliament, Reign of Richard II, vol. III Irish Sources: Oversize 4A Inquisitionum in Officio Rotulorum Cancellariae Hiberniae asservatarum Irish Sources: Oversize 4A Repertorium, vol. I Patent Rolls Henry II-Henry VII. Rotulorum Patentium et Clausorum Cancellariae Irish Sources: Oversize 4A Hiberniae Calendarium Calendar of the Irish Patent Rolls of James I Irish Sources: Oversize 4A Einhardi Vita Karoli Magni Sources 5B Rolls of Parliament. Edward I & II, vol. I Irish Sources: Oversize 4A Rolls of Parliament. Edward III, vol. II Irish Sources: Oversize 4A Rolls of Parliament. Edward IV, vol.VI Irish Sources: Oversize 4A Transcripts of Charters and Privileges to cities, Towns, Abbeys and other Bodies Corporate Irish Sources: Oversize 4A 18 Henry II to 18 Richard II (1171-1395) Ninth Report of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscript. Irish Sources: Oversize 4A Part II, Appendix & Index Pleas before Theobald de Verdun, Irish Sources 4A Justiciar of Ireland Pleas of the Crown before Edward le Botilla, Irish Sources 4A Justiciar of Ireland Laws of Breteuil. (2 vols. Bound in Orange Plastic Covers) Irish Sources 4A Calendar of the Justiciary Rolls or the Proceedings in the Court of Justiciar Irish Sources: Central of Ireland preserved in the Public Record 4B Administration Office of Ireland. 1st -7th Years of the reign of Edward II(1308-1314) Calendar of Memoranda Rolls (Exchequer) Irish Sources: Central 4B Michaelmas 1326-Michaelmas 1327 Administration Author Title Section Name Shelf Irish Sources: Sancti Bernardi Opera vol.I 4D Ecclesiastical Irish Sources: Sancti Bernardi Opera vol.II 4D Ecclesiastical Irish Sources: Sancti Bernardi Opera vol.III 4D Ecclesiastical Irish Sources: Sancti Bernardi Opera vol.IV 4D Ecclesiastical Irish Sources: Sancti Bernardi Opera vol. -

Jurisdiction in the English Atlantic, 1603-1643

Legal Settlements: Jurisdiction in the English Atlantic, 1603-1643 Ryan Matthew Bibler San Jose, CA Bachelor of Arts, California State University, Sacramento, 2007 Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia May, 2015 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the proliferation of English jurisdictions that accompanied and in many ways drove early seventeenth century English Atlantic settlement. It presents a process of jurisdictional definition, refinement, and performance by which the king, his council, and all the proprietors, governors, and planters engaged in Atlantic enterprise established frameworks for government in the king’s Atlantic dominions. In establishing English jurisdictions in Atlantic places, these actors both extended England’s legal regime to new shores and also integrated places like Barbados and Virginia into the king’s composite monarchy. The dissertation seeks to integrate two historiographies that are often held distinct: the story of domestic English legal development and the story of “imperial” legal development. By viewing legal development and English Atlantic settlement through the lens of jurisdiction this study shows that the domestic and the imperial were inextricably intertwined. Yet the novel circumstances of Atlantic settlement prompted significant legal innovation, particularly as the prominent model of colonial government shifted from corporate authority to proprietorial authority. As jurisdiction became commoditized with the introduction of proprietary grants, colonial legal development began to diverge and the possibility of a distinct imperial sphere began to emerge, though it remained nebulous and ill-formed. -

The Regimes of Somerset and Northumberland

RE-WRITING THE HISTORY OF TUDOR POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT: THE REGIMES OF SOMERSET AND NORTHUMBERLAND BY DALE HOAK Professor Hoak is a member of the history department at the College of William and Mary OR sheer drama, few periods in English history can compare with the shock-ridden reign of Edward VI (i547-1553). Infla- Ftion, war, rebellion, plague, famine, political scandal—national calamities of every sort, it seemed, visited England in these years, dis- asters punctuated, as it were, by the ultimate tragedy of the king's pre- mature death (6 July 1553). At fifteen, three years before his majority, this bright lad, whose portraits picture him so jauntily daggered and plumed, died hairless and pitiful, the nearly comatose victim of tubercu- losis and colds. The boy's end was all the more poignant since in life this Renaissance prince, so full of promise and learning, gave only his name to a reign: in fact he was a crowned puppet, his kingly authority divided among the members of a band of avaricious courtiers who, in their quest to dominate him and his powers of patronage, predictably fell out, their hatreds and jealousies erupting publicly in treasons and state trials. At the center of this struggle for power and authority stood the two great personalities of the age, Edward Seymour, duke of Somerset, and John Dudley, earl of Warwick and (after 1551) duke of Northumber- land. For six and a half years these two successively governed England, acting essentially as de facto kings. As England's designated Lord Pro- tector, Somerset survived at the top until October 1549 when his office was abolished in a couf d'état directed in part by Northumberland, a man so obsessed by the threat of Somerset's subsequent opposition that he was driven finally to arrange for Somerset's execution (January 1552). -

Revised & Renumbered List 17.11.2015V2.Xlsx

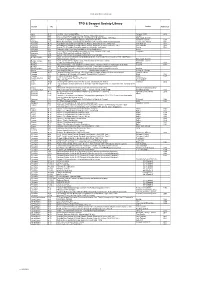

TPO Seapost Society Library List TPO & Seapost Society Library Country Ref Title Author Published . Aden M 75 Bombay - Aden Seapost Office Dovey & Bottrill 2012 Africa M25 No 11 Cockrill series Woerman Line, History, Ships and Cancels Cockrill Africa M30 No 41 Cockrill series Mailboat Service from Europe to Belgian Congo, 1879-1922 Güdenkauf, Cockrill Africa R 52 The TPOs of Imperial Military Railways (Anglo-Boer War PS) Griffiths & Drysdall, 1997 Argentina R 46 Matasellos Utilizados en las Estafetas Ambulantes Ferroviarias 1865-1892 (in Spanish) Ceriani & Kneitschel 1987 Australia M 70 Australia,New Zealand UK Mails Rates & Routes ;Ships Out & Home 1880. Vol 1 Colin Tabeart 2011 Australia M 70 Australia,New Zealand UK Mails Rates & Routes ;Ships Out & Home 1881-1900. Vol 2 Colin Tabeart 2011 Australia R 11 Victoria: The Travelling Post Offices and their Markings, 1865-1912 Purves 1955 Australia R 12 Postmarks of the Travelling Post Offices of New South Wales Dovey Australia R 53 The TPOs of South Australia (Donated by the Stuart Rossiter Trust Fund) Presgrave Australia R 87 Victoria, TPOs and their markings, 1865-1912 Austria R 25 German TPO cancels in occupied Austria 1938-1945 and after. Belgian Congo M32 No 43 Cockrill series Belgian Congo Mailboat Steamers on Congo Rivers & Lakes, 1896-1940 Postal History and Cancellations Gudenkauf, Cockrill Belgian CongoM33No 44 Cockrill series Belgian Congo. Postal History of the Lado Enclave Gudenkauf, Cockrill Belgium R 19 Les Bureaux Ambulants de Belgique D'Hondt 1936 Belgium R 20 Atlas Chronologique et Description des Obliterations et Marques Postales ''Ambulants'' de Belgique Creuven 1949 Belgium R 69 Les Bureaux Ambulants De Belgique. -

Imagining a Constitutional World of Legislative Supremacy

WHAT IF MADISON HAD WON? IMAGINING A CONSTITUTIONAL WORLD OF LEGISLATIVE SUPREMACY ALISON L. LACROIX* INTRODUCTION In the summer of 1787, when the delegates to the Constitutional Convention gathered in Philadelphia, one of the most formidable hurdles they faced was building a functional federal government that contained more than one sovereign. Throughout much of the colonial period, British North American political thinkers had challenged the orthodox metropolitan insistence on unitary sovereignty vested in Parliament, and the accompanying metropolitan aversion to any constitutional system that appeared to create an imperium in imperio, or a sovereign within a sovereign.1 By the 1780s, despite much disagreement among the members of the founding generation as to the precise balance between sovereigns, both political theory and lived experience had convinced Americans that their system could, and indeed must, not just accommodate but also depend upon multiple levels of government.2 Identifying the proper degree of federal supremacy and the best means of building it into the constitutional structure were thus central concerns for many members of the founding generation.3 Their real project was an institutional one: whether—which soon became how—to replace the highly decentralized, legislature-centered structure of the Articles of Confederation with a more robust, multi-branch general government to serve as the constitutional hub connecting the state spokes. In preparing for the convention, Virginia delegate James Madison, who was at the