THE POST OFFICE OF: INDIA GROUI' of SENIOR On·'Leers of the I'ost OFFICE L~ 1884 1'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The King's Post, Being a Volume of Historical Facts Relating to the Posts, Mail Coaches, Coach Roads, and Railway Mail Servi

Lri/U THE KING'S POST. [Frontispiece. THE RIGHT HON. LORD STANLEY, K.C.V.O., C.B., M.P. (Postmaster- General.) The King's Post Being a volume of historical facts relating to the Posts, Mail Coaches, Coach Roads, and Railway Mail Services of and connected with the Ancient City of Bristol from 1580 to the present time. BY R. C. TOMBS, I.S.O. Ex- Controller of the London Posted Service, and late Surveyor-Postmaster of Bristol; " " " Author of The Ixmdon Postal Service of To-day Visitors' Handbook to General Post Office, London" "The Bristol Royal Mail." Bristol W. C. HEMMONS, PUBLISHER, ST. STEPHEN STREET. 1905 2nd Edit., 1906. Entered Stationers' Hall. 854803 HE TO THE RIGHT HON. LORD STANLEY, K.C.V.O., C.B., M.P., HIS MAJESTY'S POSTMASTER-GENERAL, THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED AS A TESTIMONY OF HIGH APPRECIATION OF HIS DEVOTION TO THE PUBLIC SERVICE AT HOME AND ABROAD, BY HIS FAITHFUL SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. PREFACE. " TTTHEN in 1899 I published the Bristol Royal Mail," I scarcely supposed that it would be practicable to gather further historical facts of local interest sufficient to admit of the com- pilation of a companion book to that work. Such, however, has been the case, and much additional information has been procured as regards the Mail Services of the District. Perhaps, after all, that is not surprising as Bristol is a very ancient city, and was once the second place of importance in the kingdom, with necessary constant mail communication with London, the seat of Government. I am, therefore, enabled to introduce to notice " The King's Post," with the hope that it will vii: viii. -

The Royal Mail

THE EO YAL MAIL ITS CURIOSITIES AND ROMANCE SUPERINTENDENT IN THE GENERAL POST-OFFICE, EDINBURGH SECOND EDITION WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXXXV All Rights reserved NOTE. It is of melancholy interest that Mr Fawcett's death occurred within a month from the date on which he accepted the following Dedication, and before the issue of the Work. TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE HENEY FAWCETT, M. P. HER MAJESTY'S POSTMASTER-GENERAL, THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE, BY PERMISSION, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. PEEFACE TO SECOND EDITION. favour with which 'The Eoyal Mail' has THEbeen received by the public, as evinced by the rapid sale of the first issue, has induced the Author to arrange for the publication of a second edition. edition revised This has been and slightly enlarged ; the new matter consisting of two additional illus- " trations, contributions to the chapters on Mail " " Packets," How Letters are Lost," and Singular Coincidences," and a fresh chapter on the subject of Postmasters. The Author ventures to hope that the generous appreciation which has been accorded to the first edition may be extended to the work in its revised form. EDINBURGH, June 1885. INTRODUCTION. all institutions of modern times, there is, - OF perhaps, none so pre eminently a people's institution as is the Post-office. Not only does it carry letters and newspapers everywhere, both within and without the kingdom, but it is the transmitter of messages by telegraph, a vast banker for the savings of the working classes, an insurer of lives, a carrier of parcels, and a distributor of various kinds of Government licences. -

Her Majesty's Mails

HER MAJESTY'S MAILS: HISTOEY OF THE POST-OFFICE, AND AN INDUSTRIAL ACCOUNT OF ITS PRESENT CONDITION. BY WJLLIAM LEWINS, OF THE GENEKAL POST-OFFICE. SECOND EDITION, REVISED, CORRECTED, AND ENLARGED. LONDON : SAMPSON LOW, SON, AND MAESTON, MILTON HOUSE, LUDGATE HILL. 1865. [The Right of Translation is reserved.} TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE HENRY, LOED BKOUGHAM AND VAUX ETC. ETC. ETC. WHO DURING AN UNUSUALLY LONG AND LABORIOUS LIFE HAS EVER BEEN THE EARNEST ELOQUENT AND SUCCESSFUL ADVOCATE OF ALL KINDS OF SOCIAL PROGRESS AND INTELLECTUAL ADVANCEMENT AND WHO FROM THE FIRST GAVE HIS MOST STRENUOUS AND INVALUABLE ASSISTANCE IN PARLIAMENT TOWARDS CARRYING THE MEASURE OF PENNY POSTAGE REFORM IS BY PERMISSION DEDICATED WITH FEELINGS OF DEEP ADMIRATION RESPECT AND GRATITUDE BY THE AUTHOR PBEFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. THE general interest taken in this work on its first appearance, and the favourable reception accorded to it, has abundantly- proved that many agreed with me in thinking that, in spite of the world of books issuing from the press, there were still great gaps in the "literature of social history," and that to some extent my present venture was calculated to fill one of them. That my critics have been most indulgent I have had more and more reason to know as I have gone on with the revision of the book. To make it less unworthy of the kind treatment it received, I have taken this opportunity to re-write the principal part of it, and to go over with extreme care and fidelity the remaining portion. In addition to the ordinary sources of information, of which I have made diligent and conscientious use, I have been privileged to peruse the old records of the Post-office, still carefully kept at St. -

! I9mnm 11M Illulm Ummllm Glpe-PUNE-005404 I the POST OFFICE the WHITEHALL SERIES Editld Hy Sill JAME

hlllllljayarao GadgillibraJ)' ! I9mnm 11m IllUlm ummllm GlPE-PUNE-005404 I THE POST OFFICE THE WHITEHALL SERIES Editld hy Sill JAME. MARCHANT, 1.1.1., 1.L.D:- THE HOME OFFICE. By Sir Edward Troup, II.C.B., II.C.".O. Perma",,'" UtuUr-S_.uuy 01 SIIJU ill tJu H~ 0ffiu. 1908·1922. MINISTRY OF HEALTH. By Sir Arthur Newsholme. II.C.B. ".D., PoIl.C.P.. PriMpiM MId;';; OjJiur LoetII Goo_"'" B04Id £"gla"d ..... WiMeI 1908.1919, ","g'" ill 1M .Mi"isI" 01 H..ult. THE INDIA OFFICE. By Sir Malcolm C. C. Seton, II.C.B. Dep..,)! Undn·S,erela" 01 SIal. ,;"u 1924- THE DOMINIONS AND COLONIAL OFFICES. By Sir George V. Fiddes, G.c.... G •• K.C.B. P_'" Undn-SeC1'eIA" 01 Sial. lor 1M Cokmitl. Igl().lg2l. THE POST OFFICE. By Sir Evelyn Murray, II.C.B. S_.uuy 10 1M POll Offiu.mu 1914. THE BOARD OF EDUCATION. B1 Sir Lewis Amherst Selby Blgge, BT•• II.C.B. PermaffMII S_,. III" BOMd 0/ £duUlliotlI9u-lg2,. THE POST OFFICE By SIR EVELYN MURRAY, K.C.B. Stt",ary to tht POI' Offict LONDON ~ NEW YORK G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS LTD. F7 MIIIk ""J P,.;"I,J", G,.,tli Bril";,, till. &Mpll Prinl;,,: WtIf'tt. GtII, SIf'tI'. Km~. w.e., PREFACE No Department of State touches the everyday life of the nation more closely than the Post Office. Most of us use it daily, but apart from those engaged in its administration there are relatively few who have any detailed knowledge of the problems with which it has to deal, or the machinery by which it is catried on. -

Twelfth Session, Commencing at 11.30 Am INDIAN COINS

Twelfth Session, Commencing at 11.30 am INDIAN COINS 3123 Ancient India, punched marked coinage, Magadha, Mauryan and other Empires, (400-100 B.C.), punch marked mostly square/rectangular shaped issues some round, silver karshapana, usually with set of fi ve punch marked symbols on the obverse, many with additional marks on the reverse. 3127* Very good - fi ne. (7) India, Bengal Presidency, EIC rupee, Farrukhabad mint year $100 45, (1820-1830), straight grained edge (KM.70); another Ex Jonathan Cohen Collection. rupee, year 45 (1820), plain edge, (KM.78). Extremely fi ne. (2) $100 3128 India, Bengal Presidency, EIC rupee, Farrukhabad mint year 45, (1820-1830), straight grained edge (KM.70); another rupee, year 45 (1820), plain edge, (KM.78). Extremely fi ne. (2) $100 3124* India, Native States, Bundi, silver rupee (VS 1921), 1864; half rupee (VS 1905), 1848 (KM.5,6). Nearly extremely fi ne; nearly very fi ne (the date unpublished). (2) $150 Ex Ken O'Brien Collection, Noble Numismatics Sale 46 (lot 2314) and Gray Donaldson Collection. part 3129* India, Bengal Presidency, Indian Design, Murshidabad (Calcutta) Mint, 1791-1793, Perpetual 19 san sicca series, Standard Silver Currency, in the name of Shah Alam II (A.H. 1173-1221, A.D.1759-1806), machine made silver rupee, Regnal year 19 (fi xed), with date off fl an, Privy mark crescent under Shah Alam, (KM.86) (illustrated); silver rupees, 3125* Banares mint (3), 1196, regal year 17/24 (1781-2); 1197, India, Punjab, Sikh Empire, Ranjit Singh, (VS 1856-1896, regal year 17/25 (1782-3); 1202, regal year 17/29 (1787-8); A.D. -

Revised & Renumbered List 17.11.2015V2.Xlsx

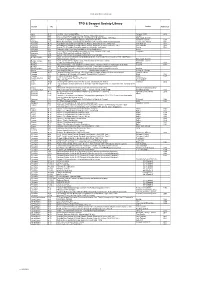

TPO Seapost Society Library List TPO & Seapost Society Library Country Ref Title Author Published . Aden M 75 Bombay - Aden Seapost Office Dovey & Bottrill 2012 Africa M25 No 11 Cockrill series Woerman Line, History, Ships and Cancels Cockrill Africa M30 No 41 Cockrill series Mailboat Service from Europe to Belgian Congo, 1879-1922 Güdenkauf, Cockrill Africa R 52 The TPOs of Imperial Military Railways (Anglo-Boer War PS) Griffiths & Drysdall, 1997 Argentina R 46 Matasellos Utilizados en las Estafetas Ambulantes Ferroviarias 1865-1892 (in Spanish) Ceriani & Kneitschel 1987 Australia M 70 Australia,New Zealand UK Mails Rates & Routes ;Ships Out & Home 1880. Vol 1 Colin Tabeart 2011 Australia M 70 Australia,New Zealand UK Mails Rates & Routes ;Ships Out & Home 1881-1900. Vol 2 Colin Tabeart 2011 Australia R 11 Victoria: The Travelling Post Offices and their Markings, 1865-1912 Purves 1955 Australia R 12 Postmarks of the Travelling Post Offices of New South Wales Dovey Australia R 53 The TPOs of South Australia (Donated by the Stuart Rossiter Trust Fund) Presgrave Australia R 87 Victoria, TPOs and their markings, 1865-1912 Austria R 25 German TPO cancels in occupied Austria 1938-1945 and after. Belgian Congo M32 No 43 Cockrill series Belgian Congo Mailboat Steamers on Congo Rivers & Lakes, 1896-1940 Postal History and Cancellations Gudenkauf, Cockrill Belgian CongoM33No 44 Cockrill series Belgian Congo. Postal History of the Lado Enclave Gudenkauf, Cockrill Belgium R 19 Les Bureaux Ambulants de Belgique D'Hondt 1936 Belgium R 20 Atlas Chronologique et Description des Obliterations et Marques Postales ''Ambulants'' de Belgique Creuven 1949 Belgium R 69 Les Bureaux Ambulants De Belgique. -

Post Office Numbers

POST OFFICE NUMBERS NUMERALS USED IN POST OFFICES IN ENGLAND WALES AND USED ABROAD 1844 TO 1969. AND THE STATUS OF OFFICES WITH NUMERAL CANCELLATIONS 1844 TO 1906. JOHN PARMENTER AND KEN SMITH. First published in 2003 by John Parmenter, 23 Jeffreys Road, London SW4 6QU. © John Parmenter and Ken Smith 2003. ISBN 0 9511395 6 8 Printed and published by John Parmenter, 23 Jeffreys Road, London SW4 6QU. CONTENTS A….INTRODUCTION B….ALL OFFICES IN NUMERICAL ORDER C….ALL OFFICES IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER D….ALL OFFICES IN COUNTY ORDER:- ENGLAND AND WALES USED ABROAD MAILBOATS RAILWAY STATION OFFICES RAILWAY TPO’S E….RAILWAY SUB OFFICES THAT USED BARRED NUMERAL CANCELS F….NUMERAL ERRORS G…LONDON OFFICES IN NUMERICAL ORDER H…LONDON OFFICES IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER I…LONDON OFFICES BY COUNTY, THEN ALPHABETICAL ORDER J…LONDON OFFICES BY DISTRICT, THEN ALPHABETICAL ORDER This book contains two parts: 1/ A list of all the numeral allocations to Post Offices in the official lists of England, Wales and Used Abroad. Much of this information has previously been available but in separate publications. Brumell stopped in 1906, which was the last official list available when numeral cancellations were still in widespread use. However the allocation of new numerals continued until 1967. 2/ A list of the status of each office that was allocated a numeral cancellation, for the period 1844 to 1906. This can explain where outgoing mail from an office was cancelled. Of particular interest is the use of barred numeral cancellations of a superior office on mail from a subordinate office during a period when the latter had a number allocated to it. -

The Royal Mail

- и Г s f-a M S ' п з $ r THE HOYAL MAIL í THE E 0 Y A L MAIL ITS CURIOSITIES AND ROMANCE BY JAMES WILSON HYDE SUPERINTENDENT IN THE GENERAL POST-OKKICK, EDINBURGH THIRD EDITION LONDON SIMPKIN, MARSHALL AND CO. MDCCCLXXXIX. A ll Eights reserved. N ote. —It is of melancholy interest that Mr Fawcett’s death occurred within a month from the date on which he accepted the following Dedication, and before the issue of the Work. \ то THE RIGHT HONOURABLE HENRY FAWCETT, M. P. h e r m a je s t y 's po stm a ste r -g e n e r a l , THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE, BY PERMISSION, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION. ГПНЕ second edition of ‘ The Royal Mail ’ having been sold out some eighteen months ago, and being still in demand, the Author has arranged for the publication of a further edition. Some additional particulars of an interest ing kind have been incorporated in the work; and these, together with a number of fresh illustrations, should render ‘ The Royal Mail ’ still more attractive than hitherto. The modem statistics have not been brought down to date; and it will be understood that these, and other matters (such as the circulation of letters), which are sub ject to change, remain in the work as set forth in the first edition. E d in b u r g h , Febrtuiry 1889. PREFACE TÔ SECOND EDITION. ГГШЕ favour with which ‘ The Royal Mail’ has been received by the public, as evinced by the rapid sale of the first issue, has induced the Author to arrange for the publication of a second edition. -

A Comparative Analysis of Translated Punjabi Folk Tale Editions, From

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Once Upon a Time in the Land of Five Rivers: A Comparative Analysis of Translated Punjabi Folk Tale Editions, from Flora Annie Steel’s Colonial Collection to Shafi Aqeel’s Post-Partition Collection and Beyond A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in English Literature Massey University, Manawatu Campus, New Zealand Noor Fatima, 2019 i Abstract This thesis offers a critical analysis of two different collections of Punjabi folk tales which were collected at different moments in Punjab’s history: Tales of the Punjab (1894), collected by Flora Annie Steel and, Popular Folk Tales of the Punjab (2008) collected by Shafi Aqeel and translated from Urdu into English by Ahmad Bashir. The study claims that the changes evident in collections of Punjabi folk tales published in the last hundred years reveal the different social, political and ideological assumptions of the collectors, translators and the audiences for whom they were disseminated. Each of these collections have one prior edition that differs in important ways from the later one. Steel’s edition was first published during the late-colonial era in India as Wide- awake Stories in 1884 and consisted of tales that she translated from Punjabi into English. Aqeel’s first edition was collected shortly after the partition of India and Pakistan, as Punjabi Lok Kahaniyan in 1963 and consisted of tales he translated from Punjabi into Urdu. -

Railways: Royal Mail Services, 2003

Railways: Royal Mail services, 2003- Standard Note: SN/BT/2251 Last updated: 13 April 2010 Author: Louise Butcher Section Business and Transport On 6 June 2003 the Royal Mail announced that it was going to withdraw its entire rail network of services for mail distribution by March 2004, in favour of a road-based distribution network. The Government’s view was that the carriage of mail by rail was a commercial issue between the Royal Mail and its contractors and that they were essentially two private companies that were involved in commercial negotiations. In January 2004, Royal Mail ran what was then thought to be its last Travelling Post Office, supposedly ending 166 years of service. Less than six months later the company announced that it was in talks to re-establish some kind of rail distribution and delivery service and was negotiating with GB Railfreight. Services were revived on a trial basis at the end of 2004 and in May 2005 Royal Mail signed a contract with GB Railfreight for a least two nightly rail services between London and Scotland until March 2006, this was subsequently extended to 2007 and then to 2010. Information on other rail issues can be found on the Railways topical page of the Parliament website. Contents 1 The end of Royal Mail’s rail contract, 2003-04 2 1.1 Royal Mail’s decision, impact on freight and view of the Government 2 1.2 Opposition to the end of services 5 2 Return of mail services, 2004- 6 This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. -

Serial Active Designation Or Undertaking?

Serial Active Designation Description of Record or Artefact Registered Disposal to / Date of Designation, Class or Undertaking? Number Current Designation Designation or Responsible Meeting Undertaking Organisation 1 YES Brunel Drawings: structural drawings produced 1995/01 Network Rail 22/09/1995 Designation for Great Western Rly Co or its associated Infrastructure Ltd Companies between 1833 and 1859 [operational property] 2 NO The Gooch Centrepiece 1995/02 National Railway 22/09/1995 Disposal Museum 3 NO Classes of Record: Memorandum and Articles 1995/03 N/A 24/11/1995 Designation of Association; Annual Reports; Minutes and working papers of main board; principal subsidiaries and any sub-committees whether standing or ad hoc; Organisation charts; Staff newsletters/papers and magazines; Files relating to preparation of principal legislation where company was in lead in introducing legislation 4 NO Railtrack Group PLC Archive 1995/03 National Railway 24/11/1995 Disposal Museum 5 YES Class 08 Locomotive no. 08616 (formerly D 1996/01 London & 22/03/1996 Designation 3783) (last locomotive to be rebuilt at Swindon Birmingham Works) Railway Ltd 6 YES Brunel Drawings: structural drawings produced 1996/02 BRB (Residuary) 22/03/1996 Designation for Great Western Rly Co or its associated Ltd Companies between 1833 and 1859 [Non- operational property] 7 YES Brunel Drawings: structural drawings produced 1996/02 Network Rail 22/03/1996 Designation for Great Western Rly Co or its associated Infrastructure Ltd Companies between 1833 and 1859 [Non- operational -

The American Revenuer, Along the Lines of a Reprint Also Individual

Tbe A mer1• can Revenuer Journal of the American Revenue Associat/On Vol. 31, No. 8, Whole No.298 October, 1977 Herrick Family Medicine Company Printed Precancels on RS95 and RS 118 Richard F. Riley The small one cent red "plasters" stamp of Dr. Herrick Type designations by Beaumont (Supplement The American ~118, was the first of the private die proprietary stamp~ Revenuer, 26(8), 1972). ' 1SSued. Between ~ovember 18, 1862 and May 17, 1883 nearly Different styles of overprint are illustrated and the Type ·12,~,000 were printed; roughly 8,300,000'on old paper, 1,800,000 lndicated under the illustration. on ~ paper and 1,800,~ on pink and. watermarked paper combmed. Except for the pink paper variety all are relatively The Types given above are cross referenced to the Types common. As collectors of the U. S. private die proprietaries given in the Historical Reference List of the Revenue Stamps of know, these stamps commonly are found overprinted in black or the United States, Toppan, et al., 1899, in appropriate places. red ink with the initials of the company name, H: F. M., and It seems likely that the overprints could be 'plated' because of often with date as well, all in various sizes of type. Indeed the wealth of variety in the overprint if sufficient multiples were according to Holcombe, the pink paper variety is known only available. However it appears that far too few multiples precancelled (Stamp & Cover Collecting, Oct., 1936). particularly vertical ones now exist to permit this. Because of Since the first of these precancels appeared at least as early the huge number of both RS95 and RS118 which were used, the as February 1870, these as well as the precancels on the first list below can only be considered a first attempt to list known issue revenues of 1862-71, clearly belong in the category of varieties on these stamps.