Inclusion International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real-Time Static Gesture Detection Using Machine Learning By

Real-time Static Gesture Detection Using Machine Learning By Sandipgiri Goswami A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Computational Sciences The Faculty of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario, Canada © Sandipgiri Goswami, 2019 THESIS DEFENCE COMMITTEE/COMITÉ DE SOUTENANCE DE THÈSE Laurentian Université/Université Laurentienne Faculty of Graduate Studies/Faculté des études supérieures Title of Thesis Titre de la thèse Real time static gesture detection using machine learning Name of Candidate Nom du candidat Goswami, Sandipgiri Degree Diplôme Master of Science Department/Program Date of Defence Département/Programme Computational Sciences Date de la soutenance Aprill 24, 2019 APPROVED/APPROUVÉ Thesis Examiners/Examinateurs de thèse: Dr. Kalpdrum Passi (Supervisor/Directeur de thèse) Dr. Ratvinder Grewal (Committee member/Membre du comité) Dr. Meysar Zeinali (Committee member/Membre du comité) Approved for the Faculty of Graduate Studies Approuvé pour la Faculté des études supérieures Dr. David Lesbarrères Monsieur David Lesbarrères Dr. Pradeep Atray Dean, Faculty of Graduate Studies (External Examiner/Examinateur externe) Doyen, Faculté des études supérieures ACCESSIBILITY CLAUSE AND PERMISSION TO USE I, Sandipgiri Goswami, hereby grant to Laurentian University and/or its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my thesis, dissertation, or project report in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or for the duration of my copyright ownership. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis, dissertation or project report. I also reserve the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis, dissertation, or project report. -

Watchtower Publications List

WATCHTOWER PUBLICATIONS LIST January 2011 This booklet contains a list of items currently available in the United States. © 2011 WATCH TOWER BIBLE AND TRACT SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA All Rights Reserved Watchtower Publications List English (S-15-E Us) Made in the United States INTRODUCTION This Watchtower Publications List (S-15) is a listing of publications and languages available to con- gregations in your branch territory. After each monthly announcement to all congregations of new publi- cations available is received, please feel free to add the new publications to your list. This will help you to know quickly and easily what is currently available. Each item listed is preceded by a four-digit item number. To expedite and improve the handling of each congregation’s monthly literature request, please use the four-digit item number when requesting literature using the jw.org Web site or listing items on page 4 of the Literature Request Form (S-14). Special- request items, which are marked by an asterisk (*), should only be submitted when specifically requested by a publisher. Special-request items should not be stocked in anticipation of requests. Languages are listed alphabetically in the Watchtower Publications List, with the language that it is being generated in at the beginning. Items in the Watchtower Publications List are divided into appropriate categories for each language. Within each category, items are alphabetized by the first word in the title of the publication. The catego- ries are: Annual Items Dramas Calendars Empty -

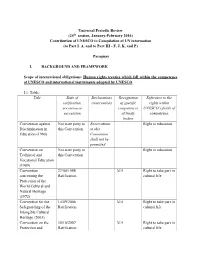

Universal Periodic Reporting

Universal Periodic Review (24th session, January-February 2016) Contribution of UNESCO to Compilation of UN information (to Part I. A. and to Part III - F, J, K, and P) Paraguay I. BACKGROUND AND FRAMEWORK Scope of international obligations: Human rights treaties which fall within the competence of UNESCO and international instruments adopted by UNESCO I.1. Table: Title Date of Declarations Recognition Reference to the ratification, /reservations of specific rights within accession or competences UNESCO’s fields of succession of treaty competence bodies Convention against Not state party to Reservations Right to education Discrimination in this Convention to this Education (1960) Convention shall not be permitted Convention on Not state party to Right to education Technical and this Convention Vocational Education (1989) Convention 27/04/1988 N/A Right to take part in concerning the Ratification cultural life Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972) Convention for the 14/09/2006 N/A Right to take part in Safeguarding of the Ratification cultural life Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003) Convention on the 30/10/2007 N/A Right to take part in Protection and Ratification cultural life 2 Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005) II. Input to Part III. Implementation of international human rights obligations, taking into account applicable international humanitarian law to items F, J, K, and P Right to education 1. NORMATIVE FRAMEWORK 1.1. Constitutional Framework1: 1. The right to education is provided in the Constitution adopted on 20 June 19922. Article 73 of the Constitution defines the right to education as the “right to a comprehensive, permanent educational system, conceived as a system and a process to be realized within the cultural context of the community”. -

Watchtower Publications List

WATCHTOWER PUBLICATIONS LIST March 2012 This booklet contains a list of items currently available in the United States. © 2012 WATCH TOWER BIBLE AND TRACT SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA All Rights Reserved Watchtower Publications List English (S-15-E Us) Made in the United States INTRODUCTION This Watchtower Publications List (S-15) is a listing of publications and languages available to con- gregations in your branch territory. After each monthly announcement to all congregations of new publi- cations available is received, please feel free to add the new publications to your list. This will help you to know quickly and easily what is currently available. Each item listed is preceded by a four-digit item number. To expedite and improve the handling of each congregation’s monthly literature request, please use the four-digit item number when requesting literature using the jw.org Web site or listing items on page 4 of the Literature Request Form (S-14). Special-request items, which are marked by an asterisk (*), should only be submitted when specifically requested by a publisher. Special-request items should not be stocked in anticipation of requests. Languages are listed alphabetically in the Watchtower Publications List , with the language that the S-15 is being generated in at the beginning. Items in the Watchtower Publications List are divided into appropriate categories for each language. Within each category, items are alphabetized by the first word in the title of the publication. The categories are: Annual Items Brochures and Booklets -

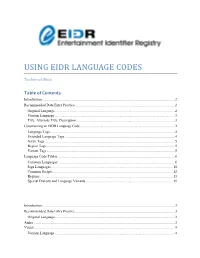

Using Eidr Language Codes

USING EIDR LANGUAGE CODES Technical Note Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommended Data Entry Practice .............................................................................................................. 2 Original Language..................................................................................................................................... 2 Version Language ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Title, Alternate Title, Description ............................................................................................................. 3 Constructing an EIDR Language Code ......................................................................................................... 3 Language Tags .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Extended Language Tags .......................................................................................................................... 4 Script Tags ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Region Tags ............................................................................................................................................. -

Covid-19 Disability Inclusive Response

PRACTICAL TOOLS for a disability inclusive COVID-19 response Source: The Leprosy Mission Note: Comprehensive guidelines, recommendations and overviews of resources on how to ensure that people with disabilities are included in COVID-19 responses can be found via WHO, IDA and IDDC / Core Group (see links page 3). In this document we aim to highlight the practical tools, such as sign language videos, easy-read materials, accessible protection methods, etc. This document will be continuously updated in the coming weeks and months (see also www.dcdd.nl/resources). DCDD gathers tools that have been developed by our network participants and other disability organisations. DCDD is not responsible for the content of these tools. Do you have tools you would like us to include? Please send an email to [email protected] Content KEY RECOMMENDATIONS & REPOSITORIES ............................................... 3 EASY-READ ................................................................................................. 4 SIGN LANGUAGE ........................................................................................ 5 INFOGRAPHICS & VISUALS ......................................................................... 7 ACCESS TO HEALTH ................................................................................... 7 PROTECTION METHODS ............................................................................. 8 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT ........................................................................ 8 Practical Tools for a disability inclusive -

Prayer Cards (216)

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Deaf in Afghanistan Deaf in Albania Population: 398,000 Population: 14,000 World Popl: 48,206,860 World Popl: 48,206,860 Total Countries: 216 Total Countries: 216 People Cluster: Deaf People Cluster: Deaf Main Language: Afghan Sign Language Main Language: Albanian Sign Language Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Minimally Reached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.05% Chr Adherents: 30.47% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: Translation Needed www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Deaf in Algeria Deaf in American Samoa Population: 223,000 Population: 300 World Popl: 48,206,860 World Popl: 48,206,860 Total Countries: 216 Total Countries: 216 People Cluster: Deaf People Cluster: Deaf Main Language: Algerian Sign Language Main Language: Language unknown Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Christianity Status: Unreached Status: Superficially reached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.28% Chr Adherents: 95.1% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: Unspecified www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Deaf in Andorra Deaf in Angola Population: 200 Population: 339,000 World Popl: 48,206,860 World Popl: 48,206,860 Total -

The Deaf of Paraguay

Profile Year: 2009 People and Language Detail Profile Language Name: Paraguayan Sign Language ISO Language Code: Not yet The Deaf Of Paraguay The Paraguayan Sign Language Community Paraguayan deaf people are located throughout the country of Paraguay, with most concentrated in the capital city of Asunción and the second largest city, Ciudad del Este. Very few deaf people live in the Chaco region of northern Paraguay. Deaf population estimates vary, but a local deaf association indicated that there are approximately 15 thousand signing deaf people in Paraguay. There are seven deaf schools, only two of which offer secondary educa- tion. Paraguayan deaf education has traditionally used oral communication where students learn speech and lip-reading instead of sign language, but has recently begun to incorporate more sign language into classrooms. Some deaf students are integrated into special education or regular hearing classrooms with or without interpreters. Deaf Paraguayans typically gather at deaf associations or religious meet- ings where their indigenous sign language, Lengua de Señas del Paraguay (LSPY), is used. There are seven deaf associations located throughout Para- guay. Five signed religious services are available in the country, all in Asunción. Because deaf Paraguayans indicate that they struggle accessing Primary Religion: written Spanish materials, a translation team was formed in 2008 through Christianity Letra Paraguay to begin translating Scripture into LSPY. __________________________________________________________ Most Paraguayan deaf people typically work in manual labor jobs and Disciples (Matt 28:19): receive lower than minimum wage. They are struggling for equality with Fewer than 5% __________________________________________________________ hearing society and identify with each other as a unique Deaf Paraguayan culture. -

Universidade Federal Fluminense Edilene De Melo

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE EDILENE DE MELO TEIXEIRA DEBATES GLOTOPOLÍTICOS NA REVISTA DA FENEIS: O SURDO, A LÍNGUA PORTUGUESA E A LÍNGUA DE SINAIS Niterói 2020 II Edilene de Melo Teixeira DEBATES GLOTOPOLÍTICOS NA REVISTA DA FENEIS: o surdo, a língua portuguesa e a língua de sinais Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos de Linguagem, Linha de Pesquisa 3: História, Política e Contato Linguístico, do Instituto de Letras da Universidade Federal Fluminense, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do título de Mestre em Estudos de Linguagem. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Xoán Carlos Lagares Diez Niterói 2020 III IV Edilene de Melo Teixeira DEBATES GLOTOPOLÍTICOS NA REVISTA DA FENEIS: o surdo, a língua portuguesa e a língua de sinais Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos de Linguagem, Linha de Pesquisa 3: História, Política e Contato Linguístico, do Instituto de Letras da Universidade Federal Fluminense, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do título de Mestre em Estudos de Linguagem. Niterói, 17 de fevereiro de 2020. BANCA EXAMINADORA __________________________________________________________________________ Xoán Carlos Lagares, Doutorado, UFF – (Orientador) Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) __________________________________________________________________________ Telma Cristina de Almeida Silva Pereira, Doutorado, (membro interno) Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) __________________________________________________________________________ -

Wie Gehörlose Sprechen

Die Welt der Gebärdensprachen – wie Gehörlose sprechen Prof. Dr. Christiane Hohenstein & Andri Reichenbacher, ZHAW Vortrag für die Kinderuniversität Winterthur am 9. Januar 2019 Naturwissenschaftliche Gesellschaft Winterthur (NGW) Departement Schule und Sport der Stadt Winterthur, Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Schweiz Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften der NGW ©https://www.annabelle.ch/l eben/gesellschaft/wenn-man- als-gehoerlose-karriere- macht-47540 [21.12.2018] Gehörlose haben von Geburt an oder durch eine Krankheit kein Was sind Hörvermögen - oder nur eine geringe Resthörfähigkeit. Sie haben eine Stimme, können sich selbst beim Sprechen aber nicht „Gehörlose“? hören. Deshalb ist es für Gehörlose schwer sprechen zu lernen. Sie können nicht übers Ohr kontrollieren, was sie sagen. Wenn Gehörlose ihre Stimme gebrauchen, hört es sich für Hörende ungewohnt an. Es kann für Hörende schwer zu verstehen sein, wenn Gehörlose sprechen. Es gibt in der Schweiz ca. 10‘000 Gehörlose. Bevölkerung Schweiz 9000000 8000000 Wie viele 7000000 Gehörlose gibt 6000000 5000000 es? 4000000 3000000 2000000 1000000 0 Anzahl Schweiz Bevölkerung Hörbehinderte Gehörlose ©SGB-FSS 2018 Gehörlose sind eine kleine Minderheit in der Bevölkerung. Was sind Ihre Behinderung ist nicht sichtbar. „Gehörlose“? Gehörlose wurden früher als dumm angesehen, weil sie „normal“ aussehen, sich aber nicht wie Hörende mit ihrer Stimme verständigen können. Man nannte sie „Taubstumme“. Das ist nicht richtig, weil Gehörlose eine Stimme haben; sie sind nicht stumm. Sie werden auch heute oft noch als geistig zurückgeblieben behandelt. Dabei sind sie kognitiv voll leistungsfähig. Sie können manche Dinge sogar besser als Hörende: der Sehsinn ist bei Gehörlosen viel besser geschult. Ihre natürliche Sprache ist Gebärdensprache. Sprachen der Erde Was ist eine „Gebärden- gesprochene Sprachen Gebärdensprachen Gebärdensprachen sind richtige Sprachen: mit Vokabeln, Grammatik, sprache“? Zahlwörtern, Ausdrücken für Namen, Substantive, Verben usw. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afro-Argentine in Argentina Afro-Bolivian in Argentina Population: 137,000 Population: 1,300 World Popl: 137,000 World Popl: 134,300 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: Afro-American, Hispanic People Cluster: Afro-American, Hispanic Main Language: Spanish Main Language: Spanish Main Religion: Christianity Main Religion: Christianity Status: Significantly reached Status: Significantly reached Evangelicals: 12.0% Evangelicals: 12.0% Chr Adherents: 97.0% Chr Adherents: 98.5% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afro-Caribbean, other in Argentina Afro-Paraguayan in Argentina Population: 2,900 Population: 1,900 World Popl: 113,900 World Popl: 73,900 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: Afro-American, Northern People Cluster: Afro-American, Hispanic Main Language: Spanish Main Language: Spanish Main Religion: Christianity Main Religion: Christianity Status: Significantly reached Status: Partially reached Evangelicals: 12.0% Evangelicals: 6.0% Chr Adherents: 90.0% Chr Adherents: 100.0% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afro-Peruvians in Argentina Afro-Uruguayan -

Implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

United Nations CRPD/C/PRY/1 Convention on the Rights Distr.: General 28 June 2011 of Persons with Disabilities English Original: Spanish Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Initial reports submitted by States parties under article 35 of the Convention Paraguay*, ** * In accordance with the information transmitted to States parties regarding the processing of their reports, the present document was not formally edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. ** Annexes can be consulted in the files of the Secretariat. GE.11-43801 (E) 281111 061211 CRPD/C/PRY/1 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1–3 3 II. General provisions of the Convention. Articles 1 to 4............................................ 4–9 3 III. Specific rights ......................................................................................................... 10–195 4 A. Article 5. Equality and non-discrimination .................................................... 10–19 4 B. Article 8. Awareness-raising .......................................................................... 20–23 6 C. Article 9. Accessibility ................................................................................... 24–27 6 D. Article 10. Right to life................................................................................... 28–29 7 E. Article 11. Situations