Peter Uwe Hohendahl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

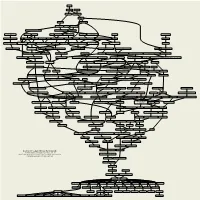

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Philosophy of Modeling in the 1870S: a Tribute to Hans Vaihinger

Baltic J. Modern Computing, Vol. 9 (2021), No. 1, pp. 67–110 https://doi.org/10.22364/bjmc.2021.9.1.05 Philosophy of Modeling in the 1870s: A Tribute to Hans Vaihinger Karlis Podnieks Faculty of Computing, University of Latvia 19 Raina Blvd., Riga, LV-1586, Latvia [email protected] Abstract. This paper contains a detailed exposition and analysis of The Philosophy of “As If“ proposed by Hans Vaihinger in his book published in 1911. However, the principal chapters of the book (Part I) reproduce Vaihinger’s Habilitationsschrift, which was written during the autumn and winter of 1876. Part I is extended by Part II based on texts written during 1877–1878, when Vaihinger began preparing the book. The project was interrupted, resuming only in the 1900s. My conclusion is based exclusively on the texts written in 1876-1878: Vaihinger was, decades ahead of the time, a philosopher of modeling in the modern sense – a brilliant achievement for the 1870s! And, in the demystification of such principal aspects of cognition as truth, understanding and causality, is he not still ahead of many of us? According to Vaihinger, what we set beyond sensations is our invention (fiction), the correspondence of which with reality cannot (and need not) be verified in the mystical, absolute sense many people expect. Keywords: fictionalism, fiction, hypothesis, dogma, sensations, reality, truth, understanding, modeling 1 Introduction “Aller Dogmatismus ist hier verschwunden,“ according to Simon et al. (2013). I suspect that by saying this regarding his book, Hans Vaihinger meant, in fact, that if people would adopt his Philosophie des Als Ob, most of traditional philosophy would become obsolete. -

The Outlawed Party Social Democracy in Germany

THE OUTLAWED PARTY SOCIAL DEMOCRACY IN GERMANY Brought to you by | The University of Texas at Austin Authenticated Download Date | 4/28/19 5:16 AM Brought to you by | The University of Texas at Austin Authenticated Download Date | 4/28/19 5:16 AM THE OUTLAWED PARTY SOCIAL DEMOCRACY IN GERMANY, 18 7 8- 1 8 9 0 VERNON L . LIDTKE PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS 196 6 Brought to you by | The University of Texas at Austin Authenticated Download Date | 4/28/19 5:16 AM Copyright © i960 by Princeton University Press ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 66-14311 Publication of this book has been aided by the Whitney Darrow Publication Reserve Fund of Princeton University Press. The initials at the beginning of each chapter are adaptations from Feder und Stichel by Zapf and Rosenberger. Printed in the United States of America by Vail-Ballou Press, Inc., Binghamton, New York Brought to you by | The University of Texas at Austin Authenticated Download Date | 4/28/19 5:16 AM CONTENTS PREFACE V I. THE EMERGENCE AND EARLY ORIENTATION OF WORKING-CLASS POLITICAL ACTION 3 The German Social and Political Context 3 Ferdinand Lassalle and the Socialist Movement: An Ambiguous Heritage 18 Political and Social Democracy in the Eisenacher Tradition: The "People's State" 27 Principles and Tactics: Parliamentarism as an Issue of Socialist Politics 32 II. THE MATURATION OF THE SOCIALIST MOVE MENT IN THE EIGHTEEN-SEVENTIES 39 The Quest for Revolutionary Identity and Organizational Unity 40 The Gotha Program as a Synthesis of Traditional Social Democratic Ideas 43 Unity between Social Democratic Theory and Practice in Politics 52 The Quest for Certainty in Economic Thought 59 On the Eve of Catastrophe: Social Democrats and German Society 66 III. -

Om Positivisme Og Objektivisme I Samfunds Videnskaberne1

Nikolaj Nottelmann Om positivisme og objektivisme i samfunds- videnskaberne1 »Positivisme« hører til de mest kontroversielle og mangetydige termer i moderne debatter om samfundsvidenskabelig metode. Bredt anvendte læ- rebøger er på én gang ofte uklare og voldsomt indbyrdes uenige angående positivismens metafysiske, erkendelsmæssige og ideologiske forpligtelser. Denne artikel leverer en receptionshistorisk behandling af positivismen fra dens dobbelte udspring i det 19. århundredes franske og tyske filosofi frem til i dag. Hermed kortlægges en række væsentlige historiske omforståelser og misforståelser som baggrund for nutidens begrebsforvirring. Det påvises efterfølgende, at forskellige positivistiske retningers forhold til videnskabe- lig objektivisme er en temmelig kompleks og varieret affære. Det er således ufrugtbart at behandle samfundsvidenskabelig positivisme og objektivisme under ét, sådan som det ofte gøres. Positivisme; Objektivisme; Fænomenalisme; Logisk Empirisme; Kritisk Teori DANSK SOCIOLOGI • Nr. 3/28. årg. 2017 9 Indledning Meget taler for, at samfundsvidenskaberne længe har befundet sig i en post- positivistisk epoke; en tid, hvor hverken disse discipliners dominerende me- toder eller toneangivende metodelære længere falder ind under »positivis- men« (jeg vil i denne artikel sætte »positivisme« i anførselstegn, hver gang termen bruges bredt og uforpligtende som her. En mere præcis terminologi indføres nedenfor). Der er således i dag meget langt mellem aktive sociologer, som åbent bekender sig til en form for »positivisme«.2 -

History of the German Struggle for Liberty

' / ~l HISTORY OF TJHE if GERMAN STRUGGLE FOR LIBERTY/ LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIC6O if03 WILLIAM THE CHEAT HISTORY OF THE GERMAN STRUGGLE FOR LIBERTY M. UNIV. YALE HON. MEMBER ROYAL A. (HON. CAUSA) ; UNITED SERVICE LIFE MEMBER AMERICAN HISTORICAL INST., LONDON ; ASSOCIATION HON. MEMBER ROYAL ARTILLERY INSTITUTION, WOOLWICH ILLUSTRATED WITH PORTRAITS - IN (THREE^VOLUMES VOL. III. 1815-1848 NEW YORK AND LONDON HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS 1903 Copyright, 1903, by HAKPKK & BBOTHKM. All riokti nuntd. Published September, 1903. THIS BOOK I DEDICATE TO THE MEMORY OF THE MANY NOBLE GERMANS who have suffered prison, exile, and death in order that their country might be United and Free. CONTENTS OF VOL. Ill I. AFTER WATERLOO 1 II. THE STUDENTS LIGHT SOME DANGEROUS FIRES ON THE WARTBURG 7 III. PRUSSIA SORELY IN NEED OF MONEY 21 IV. THE GERMAN EMPIRE COMMENCES TO TAKE FORM 29 V. BIRTH AND EARLY PRIVATIONS OF ROBERT BLUM . 35 VI. PROFESSOR AND POLITICIAN 44 VII. A CHRISTIAN SPIRIT IN GERMANY 48 VIII. DEMOCRACY AND SCHOLARSHIP 55 IX. POETRY, Music, AND PATRIOTISM 58 X. NATIONAL ART 68 ""* XI. THE EARLY YEARS OF TURNVATER JAHN .... 72 XII. STUDENT AND FIGHTER 80 POPULARIZES THE MODERN TURNS* *^~ XIII. JAHN 90 XIV. METTERNICH DECLARES TURNEN TO BE TREASON . 97 ^ XV. JAHN'S IMPRISONMENT AND DEATH 101 XVI. AIX-LA-CHAPELLE (1818) AND THE HOLY ALLIANCE 115 XVII. PRUSSIAN FREE-TRADE, 1818 123 XVIII. THE FIRST GERMAN EMPEROR EARLY YEARS . 135 XIX. JULIE KRUDENER AND THE CZAR 145 XX. THEOLOGY PATRIOTISM ASSASSINATION .... 156 XXI. CARLSBAD DECREES, 1819 173 XXII. PRUSSIA WELCOMES THE CARLSBAD DECREES . -

Les Origines De La Philosophie Du Comme Si the Origins of the As If Philosophy

Philosophia Scientiæ Travaux d'histoire et de philosophie des sciences 20-1 | 2016 Le kantisme hors des écoles kantiennes Les origines de la philosophie du comme si The Origins of the As If Philosophy Hans Vaihinger Traducteur : Christophe Bouriau Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/philosophiascientiae/1157 DOI : 10.4000/philosophiascientiae.1157 ISSN : 1775-4283 Éditeur Éditions Kimé Édition imprimée Date de publication : 25 février 2016 Pagination : 95-118 ISBN : 978-2-84174-750-4 ISSN : 1281-2463 Référence électronique Hans Vaihinger, « Les origines de la philosophie du comme si », Philosophia Scientiæ [En ligne], 20-1 | 2016, mis en ligne le 25 février 2019, consulté le 30 mars 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ philosophiascientiae/1157 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/philosophiascientiae.1157 Tous droits réservés Les origines de la philosophie du comme si∗ Hans Vaihinger (1852-1933) Traduction de Christophe Bouriau, Laboratoire Lorrain de Sciences Sociales (2L2S), Metz – Laboratoire d’Histoire des Sciences et de Philosophie, Archives H.-Poincaré, Université de Lorraine, CNRS, Nancy (France) Résumé : Nous traduisons l’article de Vaihinger « Wie die Philosophie des Als Ob entstand », paru dans Die deutsche Philosophie der Gegenwart in Selbstdarstellungen, Raymund Schmidt (éd.), Leipzig, Felix Meiner Verlag, 1921, tome 2, pp. 1–29. Cet article autobiographique retrace le parcours in- tellectuel de Hans Vaihinger dont la « philosophie du comme si », qui prend sa source majeure dans la pensée de Kant, connaît aujourd’hui une grande vitalité sous la figure du fictionalisme. Abstract: Today Vaihinger’s philosophy of “as if” enjoys wide interest as part of the renaissance of fictionalism. -

German Socialists in Exile, 1878-1890

For the Future People’s State German Socialists in Exile, 1878-1890 D.T. HENDRIKSE Cover illustration: House search of a suspected socialist, around 1879. Anonymous. Archiv der sozialen Demokratie, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, FB002461. FOR THE FUTURE PEOPLE’S STATE German Socialists in Exile, 1878-1890 Research Master History Utrecht University Supervisor Prof. Dr. Jacco Pekelder Second evaluator Dr. Christina Morina Submission 21 June 2019 Daniël Thijs Hendrikse Born 19 March 1995 Student number 4146328 Email [email protected] ‘Man wird nicht umsonst, das heißt, ohne private Ursache, Feldherr oder Anarchist oder Sozialist oder Reaktionär, und alle großen und edlen und schimpflichen Taten, die einigermaßen die Welt verändert haben, sind die Folgen irgendwelcher ganz unbedeutender Ereignisse, von denen wir keine Ahnung haben.’ Joseph Roth 2 Abstract In the years between 1878 and 1890, when Bismarck prohibited socialism in Germany with the so-called Sozialistengesetz, many German socialists went into exile abroad. Even though this was an important, formative period for German socialism, historians have been treating it as a mere intermezzo in the development of socialism rather than a crucial phase. As a result, the international exchange of ideas between the exiled socialists has long been overlooked. Drawing upon a wide array of sources, this thesis studies the transfer and diffusion of ideas. It does so by looking at four exiled Germans – Carl August Schramm, Carl Hirsch, Hermann Schlüter and Clara Zetkin – and three cities in particular – Zürich, Paris and London. Since ideas are highly personal, it is important to take into account the micro histories of the personal lives. -

Franz Brentano and Austrian Philosophy, Vienna Circle Institute Yearbook 24, 252 D

Denis Fisette • Guillaume Fréchette 72 Friedrich Stadler 73 Editors 74 Franz Brentano and Austrian 75 Philosophy 76 Chapter 12 1 Brentano and J. Stuart Mill 2 on Phenomenalism and Mental Monism 3 Denis Fisette 4 Abstract This study is about Brentano’s criticism of a version of phenomenalism 5 that he calls “mental monism” and which he attributes to positivist philosophers 6 such as Ernst Mach and John Stuart Mill. I am interested in Brentano’s criticism of 7 Mill’s version of mental monism based on the idea of “permanent possibilities of 8 sensation.” Brentano claims that this form of monism is characterized by the identi- 9 fication of the class of physical phenomena with that of mental phenomena, and it 10 commits itself to a form of idealism. Brentano argues instead for a form of indirect 11 or hypothetical realism based on intentional correlations. 12 Keywords Brentano · Stuart Mill · Mach · Positivism · Phenomenalism · 13 Permanent possibilities of sensation 14 This study is about Brentano’s relationship with positivism. This topic has been 15 investigated in connection with Comte’s and Mach’s versions of positivism, and it 16 has been argued that the young Brentano was significantly influenced by several 17 aspects of Comte’s positive philosophy without ever committing himself to its anti- 18 metaphysical assumptions.1 But several other aspects of Brentano’s relationship 19 with positivism have not been thoroughly investigated; namely, Brentano’s 20 1 See Münch, D. (1989), „Brentano and Comte“, in: Grazer Philosophische Studien, vol. 35, phi- losophiques de Strasbourg, vol. 35, pp. -

Mitteilungen Aus Dem Brenner-Archiv Nr. 27/2008 Gedruckt Mit Unterstützung Des Amtes Der Tiroler Landesregierung (Kulturabteilung) Und Der Stadt Innsbruck (Kulturamt)

Mitteilungen aus dem Brenner-Archiv Nr. 27/2008 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Amtes der Tiroler Landesregierung (Kulturabteilung) und der Stadt Innsbruck (Kulturamt) ISSN 1027-5649 Eigentümer: Brenner-Forum und Forschungsinstitut Brenner-Archiv Innsbruck 2008 Bestellungen sind zu richten an: Forschungsinstitut Brenner-Archiv Universität Innsbruck (Tel. +43512 507-4511) A-6020 Innsbruck, Josef-Hirn-Str. 5 http://brenner-archiv.uibk.ac.at/ Druck: Steigerdruck, 6094 Axams, Lindenweg 37 Herausgeber: Johann Holzner und Eberhard Sauermann Satz: Barbara Halder und Christoph Wild Layout und Design: Christoph Wild Nachdruck oder Vervielfältigung nur mit Genehmigung der Herausgeber gestattet © 2008 Universität Innsbruck - Vizerektorat für Forschung Alle Rechte vorbehalten. http://www.uibk.ac.at/iup/ Inhalt Editorial 5 Texte Alois Hotschnig: Besorgungen für den Tag 7 Joseph Zoderer: Aus dem Notizblock 1964 11 Reden Anna Rottensteiner: Laudatio anlässlich der Verleihung des Tiroler Landespreises für Kunst an Alois Hotschnig 13 Johann Holzner: Laudatio anlässlich der Verleihung der Ehrenbürgerschaft der Universität Innsbruck an Joseph Zoderer 17 Christian Haller: Ich möcht ein solcher werden wie einmal ein andrer gewesen ist. Vom Wandel des Menschenbildes und der theatralischen Figur 19 Klaus Müller-Salget: Against Resignation Abschiedsvorlesung an der Universität Innsbruck 25 Aufsätze Eberhard Sauermann: Anthologien der NS-Zeit mit Gedichten Trakls 37 Árpád Bernáth: Fortschreibung und Kommentierungsbedarf Über die „Kölner Ausgabe“ der Werke Heinrich Bölls 51 Dossier: Christine Lavant und Russland 71 Wolfgang Wiesmüller: Facetten der österreichischen Lyrik nach 1945 Am Beispiel biblisch-christlicher Intertextualität bei Christine Lavant und Christine Busta 75 Nina Pavlova: Christine Lavant und das Gesetz ihrer Dichtung 93 Natalia Bakshi: Der Einfl uss der russischen Literatur auf Christine Lavants „Aufzeichnungen aus einem Irrenhaus“ 101 Dirk Kemper: Überblendungstechnik und literarische Moderne Zu Christine Lavants „Das Kind“ 111 Ursula A. -

Reformation and Scholasticism in Philosophy

THE COLLECTED WORKS OF HERMAN DOOYEWEERD Series A, Volume 5 GENERAL EDITOR: D.F.M. Strauss Reformation and Scholasticism in Philosophy VOLUME I THE GREEK PRELUDE Herman Dooyeweerd Paideia Press 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dooyeweerd, H.(Herman), 1884-1977. Reformation and Scholasticism in Philosophy Herman Dooyeweerd. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 978-0-88815-215-2 [CWHD A5] (soft) This is Series A, Volume 5 in the continuing series The Collected Works of Herman Dooyeweerd (Initially published by Mellen Press, now published by Paideia Press) ISBN 978-0-88815-215-2 The Collected Works comprise a Series A, a Series B, and a Series C (Series A contains multi-volume works by Dooyeweerd, Series B contains smaller works and collections of essays, Series C contains reflections on Dooyeweerd's philosophy designated as: Dooyeweerd’s Living Legacy, and Series D contains thematic selections from Series A and B) A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. The Dooyeweerd Centre for Christian Philosophy Redeemer University College Ancaster, Ontario CANADA L9K 1J4 All rights reserved. For information contact: ÓPAIDEIA PRESS 2012 Grand Rapids, MI 49507 Printed in the United States of America Reformation and Scholasticism in Philosophy by Herman Dooyeweerd Volume I THE GREEK PRELUDE Translated by Ray Togtmann Initial Editor the Late Robert D. Knudsen Final Editor Daniël Strauss Editing of All Greek Quotations by Al Wolters This is Volume I of a three-volume work. Volume I first appeared in 1949 under the title: Reformatie en Scholastiek in de Wijsbegeerte (T. -

Ethik Und Moral Im Wiener Kreis

Anne Siegetsleitner Ethik und Moral im Wiener Kreis Zur Geschichte eines engagierten Humanismus 2014 Böhlau Verlag Wien. Köln. Weimar Veröffentlicht mit Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund ( FWF ): PUB 120-V23 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://portal.dnb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung : Anonymes Plakat , inspiriert von Otto Neuraths Bildstatistik aus den 1930er-Jahren , datiert 1962. Foto : ÖNB Sign. FLU 00231223 © 2014 by Böhlau Verlag Ges. m. b. H & Co. KG , Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1 , A-1010 Wien , www.boehlau-verlag.com Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Lektorat : Jörg Eipper-Kaiser , Graz Umschlaggestaltung : Michael Haderer , Wien Satz : Carolin Noack , Wien Druck und Bindung : Finidr, Cesky Tesin Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefreiem Papier Printed in the EU ISBN 978-3-205-79533-9 Für Stefan und Sophia Danksagung Eine Untersuchung wie die vorliegende , die eine überarbeitete Fassung meiner 2012 an der Universität Salzburg eingereichten Habilitationsschrift darstellt , verdankt sich vieler- lei Anstößen , Institutionen und Personen. Namentlich hervorheben möchte ich zuvorderst Edgar Morscher und Otto Neumai- er , die ihr Entstehen als Ansprechpartner über Jahre hinweg hinterfragend und aufmun- ternd begleiteten. Danken möchte ich darüber hinaus den vielen Kolleginnen und Kollegen , die bei ver- schiedenen Gelegenheiten bereit waren , sich mit meinen Gedanken auseinanderzusetzen , inhaltliche Anregungen zu geben oder die Arbeit auf eine andere Weise besonders för- derten. Zu nennen sind insbesondere : Massimo Ferrari , Mathias Iven , Hannes Leitgeb , Ortrud Leßmann , Thomas Mormann , Elisabeth Nemeth , Monika Neuhofer , Jan Radler , Anne Reichold , Günther Sandner , Friedrich Stadler sowie mehrere anonyme Gutachte- rinnen und Gutachter. -

130 New Books. It, When Standing As Copula, Gives No Indication Which Kind of Condition Is Intended by the Proposition

130 New Books. it, when standing as copula, gives no indication which kind of condition is intended by the proposition. And therefore I was careful to interpret the it in the 'cogito' by the word meant, having shown the ' cogito to express only what existence was, and not how it arose nor how it was inferred. Mr. Main, in recurring to the unanalysed use of it, really unsays Descartes' proposition. BHADWOETH H. HODGBOK.] XTL—NEW BOOKS. Downloaded from History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century. By LESLIE STHPHBN. 2 vola London i Smith, Elder & Co. Pp. 466, 469. This very important work will be reviewed at length in a future number. It is first of all, as the preface tells, a history of the Deistical movement; but for this it " seemed necessary to describe the general theological tendencies of the time, and, in order to set http://mind.oxfordjournals.org/ forth intelligibly the ideas which shaped those tendencies, it seemed desirable, again, to trace their origin in the philosophy of the time and to show their application in other departments of speculation ". The author therefore begins with an account of the contemporary Philosophy, and seeks besides " to indicate the application of the principles accepted in philosophy and theology to moral and political questions, and their reflection on the imaginative literature of the time"; though in dealing with political theories he tries to keep as far as possible from the province of political or social history. at University of Michigan on July 9, 2015 A Treatise on the Moral Ideals.