On Going Back to Kant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

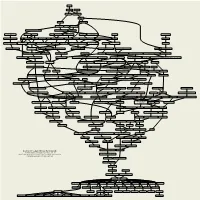

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

History and Theory of Philosophy

FEDERAL STATE BUDGETARY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF HIGHER EDUCATION "BASHKIR STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY" OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTHCARE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION (FSBEI HE BSMU MOH Russia) HISTORY AND THEORY OF PHILOSOPHY Textbook Ufa 2020 1 UDC 1(09)(075.8) BBC 87.3я7 H90 Reviewers: Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Head of the department «Social work» FSBEI HE «Bashkir State University» U.S. Vildanov Doctor of Philosophy, Professor at the Department of Philosophy and History FSBEIHE «Bashkir State Agricultural University» A.I. Stoletov History and theory of philosophy:textbook/ K.V. Khramova, H90 R.I. Devyatkina, Z.R. Sadikova, O.M. Ivanova, O.G. Afanasyeva, A.S. Zubairova-Valeeva, N.R. Mingazova, G.R. Davletshina — Ufa: Ufa: FSBEIHEBSMUMOHRussia, 2020. – 127 p. The manual was prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Federal State Educational Standard of Higher Education in specialty 31.05.01 «General Medicine» the current curriculum and on the basis of the work program on the discipline of philosophy. The manual is focused on the competence-based learning model. It has an original, uniform for all classes structure, including the topic, a summary of the training questions, the subject of essays, training materials, test items with response standards, recommended literature. This manual covers topics related to the periods of development of world philosophy. Designed for students in the specialty 31.05.01 «General Medicine». It is recommended to be published by the Coordinating Scientific and Methodological Council and was approved by the decision of the Editorial and Publishing Council of the BSMU of the Ministry of Healthcare of Russia. -

Metaphysics Today and Tomorrow*

1 Metaphysics Today and Tomorrow* Raphaël Millière École normale supérieure, Paris – October 2011 Translated by Mark Ohm with the assistance of Leah Orth, Jon Cogburn, and Emily Beck Cogburn “By metaphysics, I do not mean those abstract considerations of certain imaginary properties, the principal use of which is to furnish the wherewithal for endless dispute to those who want to dispute. By this science I mean the general truths which can serve as principles for the particular sciences.” Malebranche Dialogues on Metaphysics and Religion 1. The interminable agony of metaphysics Throughout the twentieth century, numerous philosophers sounded the death knell of metaphysics. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Rudolf Carnap, Martin Heidegger, Gilbert Ryle, J. L. Austin, Jacques Derrida, Jürgen Habermas, Richard Rorty, and, henceforth, Hilary Putnam: a great many tutelary figures have extolled the rejection, the exceeding, the elimination, or the deconstruction of first philosophy. All these necrological chronicles do not have the same radiance, the same seriousness, nor the same motivations, but they all agree to dismiss the discipline, which in the past was considered “the queen of the sciences”, with a violence at times comparable to the prestige it commanded at the time of its impunity. Even today, certain philosophers hastily spread the tragic news with contempt for philosophical inquiry, as if its grave solemnity bestowed upon it some obviousness. Thus, Franco Volpi writes: ‘Grand metaphysics is dead!’ is the slogan which applies to the majority of contemporary philosophers, whether continentals or of analytic profession. They all treat metaphysics as a dead dog.1 In this way, the “path of modern thought” would declare itself vociferously “anti- metaphysical and finally post-metaphysical”. -

Understanding Poststructuralism Understanding Movements in Modern Thought Series Editor: Jack Reynolds

understanding poststructuralism Understanding Movements in Modern Thought Series Editor: Jack Reynolds Th is series provides short, accessible and lively introductions to the major schools, movements and traditions in philosophy and the history of ideas since the beginning of the Enlightenment. All books in the series are written for undergraduates meeting the subject for the fi rst time. Published Understanding Existentialism Understanding Virtue Ethics Jack Reynolds Stan van Hooft Understanding Poststructuralism James Williams Forthcoming titles include Understanding Empiricism Understanding Hermeneutics Robert Meyers Lawrence Schmidt Understanding Ethics Understanding Naturalism Tim Chappell Jack Ritchie Understanding Feminism Understanding Phenomenology Peta Bowden and Jane Mummery David Cerbone Understanding German Idealism Understanding Rationalism Will Dudley Charlie Heunemann Understanding Hegelianism Understanding Utilitarianism Robert Sinnerbrink Tim Mulgan understanding poststructuralism James Williams For Richard and Olive It is always about who you learn from. © James Williams, 2005 Th is book is copyright under the Berne Convention. No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved. First published in 2005 by Acumen Acumen Publishing Limited 15a Lewins Yard East Street Chesham Bucks HP5 1HQ www.acumenpublishing.co.uk ISBN 1-84465-032-4 (hardcover) ISBN 1-84465-033-2 (paperback) Work on Chapter 3 was supported by British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British -

Heidegger and the Hermeneutics of the Body

International Journal of Gender and Women’s Studies June 2015, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 16-25 ISSN: 2333-6021 (Print), 2333-603X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijgws.v3n1p3 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijgws.v3n1p3 Heidegger and the Hermeneutics of the Body Jesus Adrian Escudero1 Abstract Phenomenology, Feminist Studies and Ecologism have accused Heidegger repeatedly for not having taken into account the phenomenon of the body. Without denying the validity of such critiques, the present article focuses its attention first on the question of Dasein’s neutrality and asexuality. Then it analyzes Heidegger’s remarks on temporality as the horizon of all meaning, paying special attention to its significance for Butler’s notion of performativity. Keywords: body, Dasein, gesture, performativity, temporality In Being and Time we find only one reference to corporeality in the context of Heidegger’s analysis of spatiality. Therefore, his analysis of human existence is often accused of forgetting about the body. This criticism has particular force in the field of French phenomenology. Alphonse de Waehlens, for instance, lamented the absence of the fundamental role that the body and perception play in our everyday understanding of things. Jean-Paul Sartre expanded upon this line of criticism by emphasizing the importance of the body as the first point of contact that human beings establish with their world. However, in the context of the first generation of French phenomenologists, Maurice Merleau-Ponty was undoubtedly the first whose systematic analysis of bodily perception established the basis for a revision of Heidegger’s understanding of human life (Askay, 1999: 29-35). -

The Gnosiology As Experience of the Resurrected Christ in the Liturgical Texts of the Pentecostarion

The Gnosiology as experience of the Resurrected Christ in the liturgical texts of the Pentecostarion CONTENT INTRODUCTION 4 The motif for choosing the theme 4 The stage of the theme`s research 5 The used method 5 The purpose of the research 5 Terminological clarifications 6 CHAPTER I. THE PENTECOSTARION – THE HYMNOGRAPHICAL IMAGE OF 11 THE STATE OF RESURRECTION IN JESUS CHRIST 1.1. The Pentecostarion – the Church`s Book of Cult 11 1.2. The Pentecostarion – the Relation Dogma – Cult – Knowledge 24 1.2.1. The Cult, Favorable Environment for Spreading the Faith and for Knowing the Dogma 27 1.2.2. The Church`s Cult, Guardian of the Dogma Against Heresy 30 1.2.3. The Dogma, the Cult and the Spiritual Knowledge 33 1.3. The Pentecostarion – the Doxological Dimension of the Knowledge 36 CHAPTER II. THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL FUNDAMENTALS OF THE ORTHODOX 51 GNOSIOLOGY MIRRORED IN PENTECOSTARION 2.1. Revelation and Knowledge 51 2.2. Image and Likeness of the Power of the Man of Knowing God 63 2.2.1. The Falling into Sin and the Image Corrupted through Passions 67 2.2.2. The Renewal of the Engulfed by Passion Image 68 2.3. Person - Communion - Knowledge 75 CHAPTER III THE CHRISTOLOGICAL FUNDAMENTALS OF THE ORTHODOX 84 GNOSIOLOGY MIRRORED IN PENTECOSTARION 1 3.1. The Man`s Healing into Christ – Premise of the Knowledge 84 3.1.1. The Embodiment of the Son of God 84 3.1.1.1. Jesus Christ True God and True Man 90 3.1.1.2. The Deification of the Human Nature into Christ 91 3.1.1.3. -

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer

03/05/2017 Arthur Schopenhauer (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer First published Mon May 12, 2003; substantive revision Sat Nov 19, 2011 Among 19th century philosophers, Arthur Schopenhauer was among the first to contend that at its core, the universe is not a rational place. Inspired by Plato and Kant, both of whom regarded the world as being more amenable to reason, Schopenhauer developed their philosophies into an instinctrecognizing and ultimately ascetic outlook, emphasizing that in the face of a world filled with endless strife, we ought to minimize our natural desires for the sake of achieving a more tranquil frame of mind and a disposition towards universal beneficence. Often considered to be a thoroughgoing pessimist, Schopenhauer in fact advocated ways — via artistic, moral and ascetic forms of awareness — to overcome a frustrationfilled and fundamentally painful human condition. Since his death in 1860, his philosophy has had a special attraction for those who wonder about life's meaning, along with those engaged in music, literature, and the visual arts. 1. Life: 1788–1860 2. The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason 3. Schopenhauer's Critique of Kant 4. The World as Will 5. Transcending the Human Conditions of Conflict 5.1 Aesthetic Perception as a Mode of Transcendence 5.2 Moral Awareness as a Mode of Transcendence 5.3 Asceticism and the Denial of the WilltoLive 6. Schopenhauer's Later Works 7. Critical Reflections 8. Schopenhauer's Influence Bibliography Academic Tools Other Internet Resources Related Entries 1. Life: 1788–1860 Exactly a month younger than the English Romantic poet, Lord Byron (1788–1824), who was born on January 22, 1788, Arthur Schopenhauer came into the world on February 22, 1788 in Danzig [Gdansk, Poland] — a city that had a long history in international trade as a member of the Hanseatic League. -

Einstein and the Development of Twentieth-Century Philosophy of Science

Einstein and the Development of Twentieth-Century Philosophy of Science Don Howard University of Notre Dame Introduction What is Albert Einstein’s place in the history of twentieth-century philosophy of science? Were one to consult the histories produced at mid-century from within the Vienna Circle and allied movements (e.g., von Mises 1938, 1939, Kraft 1950, Reichenbach 1951), then one would find, for the most part, two points of emphasis. First, Einstein was rightly remembered as the developer of the special and general theories of relativity, theories which, through their challenge to both scientific and philosophical orthodoxy made vivid the need for a new kind of empiricism (Schlick 1921) whereby one could defend the empirical integrity of the theory of relativity against challenges coming mainly from the defenders of Kant.1 Second, the special and general theories of relativity were wrongly cited as straightforwardly validating central tenets of the logical empiricist program, such as verificationism, and Einstein was wrongly represented as having, himself, explicitly endorsed those same philosophical principles. As we now know, logical empiricism was not the monolithic philosophical movement it was once taken to have been. Those associated with the movement disagreed deeply about fundamental issues concerning the structure and interpretation of scientific theories, as in the protocol sentence debate, and about the overall aims of the movement, as in the debate between the left and right wings of the Vienna Circle over the role of politics in science and philosophy.2 Along with such differences went subtle differences in the assessment of Einstein’s legacy to logical empiricism. -

Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics CAMBRIDGE TEXTS in the HISTORY of PHILOSOPHY

CAMBRIDGE TEXTS IN THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY IMMANUEL KANT Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics CAMBRIDGE TEXTS IN THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY Series editors KARL AMERIKS Professor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame DESMOND M. CLARKE Professor of Philosophy at University College Cork The main objective of Cambridge Textsin the History of Philosophy is to expand the range, variety and quality of texts in the history of philosophy which are available in English. The series includes texts by familiar names (such as Descartes and Kant) and also by less well-known authors. Wherever possible, texts are published in complete and unabridged form, and translations are specially commissioned for the series. Each volume contains a critical introduction together with a guide to further reading and any necessary glossaries and textual apparatus. The volumes are designed for student use at undergraduate and postgraduate level and will be of interest not only to students of philosophy, but also to a wider audience of readers in the history of science, the history of theology and the history of ideas. For a list of titles published in the series, please see end of book. IMMANUEL KANT Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics That Will Be Able to Come Forward as Science with Selections from the Critique of Pure Reason TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY GARY HATFIELD University of Pennsylvania Revised Edition cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521828246 © Cambridge University Press 1997, 2004 This publication is in copyright. -

The Outcome of Classical German Philosophy History 71600/CL

The Outcome of Classical German Philosophy History 71600/CL 85000/PSC Prof. Wolin (GC 5114) Fall 2019 [email protected] Mon. 6:30-8:30 Room: GC ?? In 1886, Friedrich Engels wrote a perfectly mediocre book, Ludwig Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy, which nevertheless managed to raise a fascinating and important question that is still being debated today: how should we go about evaluating the legacy of German Idealism following the mid-nineteenth century breakdown of the Hegelian system? For Engels, the answer was relatively simple: the rightful heir of classical German philosophy was Marx’s doctrine of historical materialism. But, in truth, Engels’ response was merely one of many possible approaches. Nor would it be much of an exaggeration to claim that, in the twentieth century, there is hardly a philosopher worth reading who has not sought to define him or herself via a confrontation with the legacy of Kant and Hegel. Classical German Philosophy – Kant, Fichte, Hegel, and Schelling – has bequeathed a rich legacy of reflection on the fundamental problems of epistemology, ontology and aesthetics. Even contemporary thinkers who claim to have transcended it (e.g., poststructuralists such as Foucault and Derrida) cannot help but make reference to it in order to validate their post- philosophical standpoints and claims. Our approach to this very rich material will combine a reading of the canonical texts of German Idealism (e.g., Kant and Hegel) with a sustained and complementary focus on major twentieth-century thinkers who have sought to establish their originality via a critical reading of Hegel and his heirs: Alexandre Kojève, Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault, Theodor Adorno, and Jürgen Habermas. -

NEW Spirit and Secularity

NAHME - CHAPTER 3 DRAFT- NOT FOR CITATION Chapter 3 Race, Religion, and Identity: the (Theo-)Politics of Kantianism and the Predicament of German Jewish Liberalism In the century since their first, limited experience of emancipation in 1812, many German Jews gained an increasing awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of appealing to civic rights and individual freedoms to seek recognition in German public institutions. On the one hand, these liberal ideals of freedom and equality, duty and obligation to the rational legal state (Rechtstaat) gave German Jews a sense of belonging to the German Fatherland and held up the image of the rights-bearing citizen as an ideal to strive toward. But on the other hand, as we saw in the previous chapter, the Jewish Question was also increasingly framed as a problem implicit in the developing discourse of liberalism and gave rise to an anxiety over the secularization of political and moral public discourse about values, norms, and social ideals in Wilhelmine Germany. The Jewish Question, as I argued, was both an epistemological and a political predicament. Whether all “Germans” acknowledged Jews as belonging to a community and fraternity of national identity is less important, however, than the diversity in normative goals represented by the introduction of a liberal philosophical worldview in Imperial Germany as the means for articulating a still inchoate national identity. And because the Jews, like many of their compatriots, participated in a collective imagining of what a “civic” identity could be, their engagement with both the liberalism and idealism of the late nineteenth century gives voice to the significant influence of 197 NAHME - CHAPTER 3 DRAFT- NOT FOR CITATION this intellectual worldview on the broader social and cultural moment. -

Philosophy of Modeling in the 1870S: a Tribute to Hans Vaihinger

Baltic J. Modern Computing, Vol. 9 (2021), No. 1, pp. 67–110 https://doi.org/10.22364/bjmc.2021.9.1.05 Philosophy of Modeling in the 1870s: A Tribute to Hans Vaihinger Karlis Podnieks Faculty of Computing, University of Latvia 19 Raina Blvd., Riga, LV-1586, Latvia [email protected] Abstract. This paper contains a detailed exposition and analysis of The Philosophy of “As If“ proposed by Hans Vaihinger in his book published in 1911. However, the principal chapters of the book (Part I) reproduce Vaihinger’s Habilitationsschrift, which was written during the autumn and winter of 1876. Part I is extended by Part II based on texts written during 1877–1878, when Vaihinger began preparing the book. The project was interrupted, resuming only in the 1900s. My conclusion is based exclusively on the texts written in 1876-1878: Vaihinger was, decades ahead of the time, a philosopher of modeling in the modern sense – a brilliant achievement for the 1870s! And, in the demystification of such principal aspects of cognition as truth, understanding and causality, is he not still ahead of many of us? According to Vaihinger, what we set beyond sensations is our invention (fiction), the correspondence of which with reality cannot (and need not) be verified in the mystical, absolute sense many people expect. Keywords: fictionalism, fiction, hypothesis, dogma, sensations, reality, truth, understanding, modeling 1 Introduction “Aller Dogmatismus ist hier verschwunden,“ according to Simon et al. (2013). I suspect that by saying this regarding his book, Hans Vaihinger meant, in fact, that if people would adopt his Philosophie des Als Ob, most of traditional philosophy would become obsolete.