Philosophy of Modeling in the 1870S: a Tribute to Hans Vaihinger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

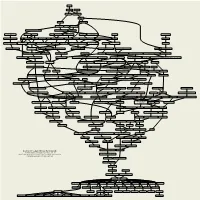

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Over Francis Bacon Van Verulam En De Methode Van Natuuronderzoek. Justus Von Liebig

Over Francis Bacon van Verulam en de methode van natuuronderzoek. Justus von Liebig. https://archive.org/details/ueberfrancisbaco00lieb/page/n9 Dit is een geannoteerde vertaling van Ueber Francis Bacon von Verulam und die Methode der Naturforschung (1863) door Justus von Liebig (1803-1873). Noten van de vertaler zijn aangegeven met nummers in teksthaken [ ]. De vertaling is geïnspireerd door een artikel van E.-J. Wagenmakers in Skepter 32.2 (zomer 2019) getiteld: ‘Het plagiaat van Lord Francis Bacon’. Liebigs verhandeling is de schriftelijke weergave van een rede voor de k. Akademie der Wisschenschaften te München op 28 maart 1863. Justus von Liebig was sinds 1859 president van deze Akademie. In Reden und Abhandlungen von Justus von Liebig, (onder redactie van M. Carriere), C. F. Winter’sche Verlagshandlung, Leipzig und Heidelberg, 1874, staat een kortere – wellicht de oorspronkelijke – versie. In deze Reden und Abhandlungen staat een tweetal zeer lezenswaardige reacties (samen nog langer dan de toespraak in de Reden zelf) op kritiek van de zijde van een professor in de filosofie, Christoph von Sigwart (Liebig schrijft Siegwart). Sigwart had uitvoerig betoogd dat Bacons filosofie nergens op sloeg, maar dat Leibig toch te streng was wat betreft Bacons relatie met de natuurwetenschap. Een Engelse vertaling verscheen in twee delen in Macmillan’s Magazine, juli en augustus 1863. Ook daarin ontbreken sommige passages die in de Duitse versie van 1863 staan. Voor de Engelse vertalingen van teksten uit Novum Organum is de vertaling van J. Spedding uit 1858 gebruikt. De vertaler Jan Willem Nienhuys Voorwoord Twintig jaar geleden had een reeks onderzoekingen naar de levensvoorwaarden van planten en dieren mij tot duidelijker inzichten gebracht dan die toentertijd golden. -

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer

03/05/2017 Arthur Schopenhauer (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer First published Mon May 12, 2003; substantive revision Sat Nov 19, 2011 Among 19th century philosophers, Arthur Schopenhauer was among the first to contend that at its core, the universe is not a rational place. Inspired by Plato and Kant, both of whom regarded the world as being more amenable to reason, Schopenhauer developed their philosophies into an instinctrecognizing and ultimately ascetic outlook, emphasizing that in the face of a world filled with endless strife, we ought to minimize our natural desires for the sake of achieving a more tranquil frame of mind and a disposition towards universal beneficence. Often considered to be a thoroughgoing pessimist, Schopenhauer in fact advocated ways — via artistic, moral and ascetic forms of awareness — to overcome a frustrationfilled and fundamentally painful human condition. Since his death in 1860, his philosophy has had a special attraction for those who wonder about life's meaning, along with those engaged in music, literature, and the visual arts. 1. Life: 1788–1860 2. The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason 3. Schopenhauer's Critique of Kant 4. The World as Will 5. Transcending the Human Conditions of Conflict 5.1 Aesthetic Perception as a Mode of Transcendence 5.2 Moral Awareness as a Mode of Transcendence 5.3 Asceticism and the Denial of the WilltoLive 6. Schopenhauer's Later Works 7. Critical Reflections 8. Schopenhauer's Influence Bibliography Academic Tools Other Internet Resources Related Entries 1. Life: 1788–1860 Exactly a month younger than the English Romantic poet, Lord Byron (1788–1824), who was born on January 22, 1788, Arthur Schopenhauer came into the world on February 22, 1788 in Danzig [Gdansk, Poland] — a city that had a long history in international trade as a member of the Hanseatic League. -

Chapter 1, the Sense and Task of Phenomenological Research

University of Alberta Heidegger’s Critique of the Cartesian Problem of Scepticism by Sean Daniel Hartford A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Philosophy ©Sean Daniel Hartford Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee Dr. Marie-Eve Morin, Philosophy, University of Alberta Dr. Robert Burch, Philosophy, University of Alberta Dr. Wesley Cooper, Philosophy, University of Alberta Dr. Leo Mos, Psychology, University of Alberta Abstract: This thesis deals with Martin Heidegger’s critique of the Cartesian problem of scepticism in Being and Time. In addition to the critique itself, Heidegger’s position with regards to the sense and task of phenomenological research, as well as fundamental ontology, is discussed as a necessary underpinning of his critique. Finally, the objection to Heidegger’s critique that is raised by Charles Guignon in his book, Heidegger and the Problem of Knowledge, (namely, that it suffers from the problem of reflexivity) is evaluated. -

Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics CAMBRIDGE TEXTS in the HISTORY of PHILOSOPHY

CAMBRIDGE TEXTS IN THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY IMMANUEL KANT Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics CAMBRIDGE TEXTS IN THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY Series editors KARL AMERIKS Professor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame DESMOND M. CLARKE Professor of Philosophy at University College Cork The main objective of Cambridge Textsin the History of Philosophy is to expand the range, variety and quality of texts in the history of philosophy which are available in English. The series includes texts by familiar names (such as Descartes and Kant) and also by less well-known authors. Wherever possible, texts are published in complete and unabridged form, and translations are specially commissioned for the series. Each volume contains a critical introduction together with a guide to further reading and any necessary glossaries and textual apparatus. The volumes are designed for student use at undergraduate and postgraduate level and will be of interest not only to students of philosophy, but also to a wider audience of readers in the history of science, the history of theology and the history of ideas. For a list of titles published in the series, please see end of book. IMMANUEL KANT Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics That Will Be Able to Come Forward as Science with Selections from the Critique of Pure Reason TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY GARY HATFIELD University of Pennsylvania Revised Edition cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521828246 © Cambridge University Press 1997, 2004 This publication is in copyright. -

The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: a Version of the Argument from Reason

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2019-04-30 The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: A Version of the Argument from Reason Hawkes, Gordon Hawkes, G. (2019). The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: A Version of the Argument from Reason (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110301 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: A Version of the Argument from Reason by Gordon Hawkes A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN PHILOSOPHY CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2019 © Gordon Hawkes 2019 i Abstract The argument from reason is the name given to a family of arguments against naturalism, materialism, or determinism, and often for theism or dualism. One version of the argument from reason is what Victor Reppert calls “the argument from the psychological relevance of logical laws,” or what I call “the argument from logical principles.” This argument has received little attention in the literature, despite being advanced by Victor Reppert, Karl Popper, and Thomas Nagel. -

Hermann Cohen's History and Philosophy of Science"

"Hermann Cohen's History and Philosophy of Science" Lydia Patton Department of Philosophy McGill University, Montreal October, 2004 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree ofPh.D. © Lydia Patton 2004 Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 0-494-06335-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 0-494-06335-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell th es es le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Foundations of Psychology by Herman Bavinck

Foundations of Psychology Herman Bavinck Translated by Jack Vanden Born, Nelson D. Kloosterman, and John Bolt Edited by John Bolt Author’s Preface to the Second Edition1 It is now many years since the Foundations of Psychology appeared and it is long out of print.2 I had intended to issue a second, enlarged edition but the pressures of other work prevented it. It would be too bad if this little book disappeared from the psychological literature. The foundations described in the book have had my lifelong acceptance and they remain powerful principles deserving use and expression alongside empirical psy- chology. Herman Bavinck, 1921 1 Ed. note: This text was dictated by Bavinck “on his sickbed” to Valentijn Hepp, and is the opening paragraph of Hepp’s own foreword to the second, revised edition of Beginselen der Psychologie [Foundations of Psychology] (Kampen: Kok, 1923), 5. The first edition contains no preface. 2 Ed. note: The first edition was published by Kok (Kampen) in 1897. Contents Editor’s Preface �����������������������������������������������������������������������ix Translator’s Introduction: Bavinck’s Motives �������������������������� xv § 1� The Definition of Psychology ���������������������������������������������1 § 2� The Method of Psychology �������������������������������������������������5 § 3� The History of Psychology �����������������������������������������������19 Greek Psychology .................................................................19 Historic Christian Psychology ..............................................22 -

Open Brunsondiss.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Liberal Arts PRAGMATISM AND THE PAST: CHARLES PEIRCE AND THE CONDUCT OF MEMORY AND HISTORY A Dissertation in Philosophy by Daniel J. Brunson © 2010 Daniel J. Brunson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2010 The dissertation of Daniel J. Brunson was reviewed and approved* by the following: Vincent M. Colapietro Liberal Arts Research Professor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Brady Bowman Assistant Professor of Philosophy Christopher Long Associate Professor of Philosophy Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies, College of Liberal Arts Jennifer Mensch Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Science, Technology, and Society William Pencak Professor of American History Nancy A. Tuana DuPont/Class of 1949 Professor of Philosophy Director, Rock Ethics Institute Director of Philosophy Graduate Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract My dissertation is entitled Pragmatism and the Past: CS Peirce on the Conduct of Memory and History. I start from the longstanding criticism that pragmatism unduly neglects the past in favor of the future. As a response, I interpret Peirce‘s pragmatism and its associated doctrines in light of his accounts of memory, history, and testimony. In particular, I follow Peirce‘s own example of a deep engagement with the history of philosophy and related fields. For example, Peirce‘s account of memory is linked to the development of a notion of the unconscious, which brings in both his work as an experimental psychologist and his interaction with figures such as Helmholtz, Wundt and James. -

Nietzsche's and Pessoa's Psychological Fictionalism

Nietzsche’s and Pessoa’s Psychological Fictionalism Antonio Cardiello* & Pietro Gori** Keywords Nietzsche; Pessoa; Vaihinger; Mead; Fictionalism; Subjectivity; Neo-Kantianism. Abstract In a note to G.R.S. Mead’s Quests Old and New, where he Found a section devoted to Hans Vaihinger’s main ideas, Fernando Pessoa reFlects on the consequences oF the Fictionalist approach to both our perception oF the I and the value oF consciousness. These questions correspond to some statements that we Find in Nietzsche’s writings, which in particular Vaihinger reFers to in his Die Philosophie des Als-ob. Our aim is thus to compare Nietzsche’s and Pessoa’s view oF the I and consciousness, and to deal with their psychology by making reFerence to Vaihinger’s Fictionalism. Palavras-chave Nietzsche; Pessoa; Vaihinger; Mead; Ficcionalismo; Subjectividade; Neokantismo. Resumo Num apontamento relacionado com a leitura de Quests Old and New de G.R.S. Mead, que revisita as teses principais de Hans Vaihinger, Fernando Pessoa reFlecte sobre as consequências de uma abordagem Ficcionalista quanto à percepção do eu e ao valor da consciência. As questões que Pessoa coloca encontram correspondência com os escritos de Nietzsche a quem Vaihinger se reFere, em particular, no seu livro Philosophie des Als-ob. O nosso intuito é o de aproFundar a comparação entre a concepção do eu e da consciência em Nietzsche e Pessoa, reconstruindo as posições de ambos nos moldes do Ficcionalismo de Vaihinger. * IFILNOVA – Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas – Universidade Nova de Lisboa. ** IFILNOVA – Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas – Universidade Nova de Lisboa. Cardiello & Gori Psychological Fictionalism Sou nada.. -

Nietzsche's Fictional Realism

P. Gori – Estetica.SR 2019/FINAL DRAFT 1 Nietzsche’s Fictional Realism: A Historico-Theoretical Approach * Pietro Gori – Instituto de Filosofia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa This is the final draft of the paper forthcoming in Estetica. Studi e Ricerche IX (2019), p. 169-184. For quotations, please make use of the published version. Abstract : At the beginning of the twentieth century, theorists developed approaches to Nietzsche’s philosophy that provided an alternative to the received view, some of them suggesting that his view of truth may be his most important and original contribution. It has further been argued that Vaihinger’s fictionalism is the paradigm within which Nietzsche’s view can be properly contextualized. As will be shown, this idea is both viable and fruitful for solving certain interpretive issues raised in recent Nietzsche scholarship. Keywords : Truth, Knowledge, Instrumentalism, Fictionalism 1. A new paradigm «I believe he is much better than his reputation suggests».1 Hans Kleinpeter wrote this of Nietzsche in a letter to Ernst Mach dated December 22, 1911. Kleinpeter was apparently reacting to Mach’s biased opinion, which likely reflected how Nietzsche was received at the time: Nietzsche, the Antichrist and immoralist who pretended to have finally gotten rid of Christian morality; Nietzsche, the philologist turned philosopher who had developed an original interpretation of the ancient Greeks; Nietzsche, the philosopher poet who wrote Thus Spoke Zarathustra and imagined «an overweening “superman” who – as Mach declared in The Analysis * Nietzsche’s works are cited by abbreviation, chapter title or number (when applicable) and section number (e.g. GM III, 24).