Hermann Cohen's History and Philosophy of Science"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weltanschauung, Weltbild, Or Weltauffassung? Stein on the Significance of Husserl’S Way of Looking at the World

Weltanschauung, Weltbild, or Weltauffassung? Stein on the Significance of Husserl’s Way of Looking at the World George Heffernan Online Conference: Stein’s and Husserl’s Intertwined Itineraries 1916–25: With Focus on Ideas II In Cooperation with the Center for the History of Women Philosophers and Scientists University of Paderborn May 20–21, 2021 Abstract In her doctoral dissertation, Zum Problem der Einfühlung (1916), Stein attempted to complement Husserl’s work on the phenomenology of intersubjectivity by providing a description of empathy and its key role in the mutual constitution of whole persons. Because he thought that her work anticipated certain ideas from the second part of his Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie, Husserl demurred at publishing it in his Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung. He did, however, engage Stein as his private assistant, and as such she helped him edit, between 1916 and 1918, his Ideas II. In the process, Stein’s interventions may have introduced views different from and possibly foreign to Husserl’s, and the new Husserliana edition of Ideas IV/V (2021) aims to sort things out. This paper seeks to contextualize the debate about the philosophical relationship between Stein and Husserl between 1916 and 1925 by drawing on two other sets of texts: (1) Stein’s several contributions to understanding Husserl’s transcendental phenomenology from 1924 to 1937, for example, “Die weltanschauliche Bedeutung der Phänomenologie” (1930/31); and (2) Husserl’s “Fichte Lectures” (1917/18), his “Kaizo Articles” (1922–24), and his “Reflections on Ethics from the Freiburg Years” (1916–37). -

Johann Friedrich Herbart Metaphysics, Psychology, and Critique of Knowledge

Надя Моро – Научно-исследовательский семинар – Бакалавриат 4-й курс, 2 модуль 2014/2015 National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow Bachelor’s programme: 4th year, module 2 SYLLABUS OF RESEARCH SEMINAR Johann Friedrich Herbart Metaphysics, psychology, and critique of knowledge Outline During the course, students will be provided with a systematic introduction to the core conceptual issues of Johann Friedrich Herbart’s theoretical philosophy: general metaphysics and psychology. Herbart (Oldenburg, 1776–Göttingen, 1841) was a major German philosopher, who held Kant’s chair in Königsberg (1809–1833) and opposed German idealism from a realist perspective. Not only did he influence subsequent philosophy in the German, Austrian, and Bohemian areas to a great extent―suffice it to mention Lotze, Hanslick, Mach, Cohen, Husserl, as well as the numerous ‘Herbartians’: Hartenstein, Zimmermann, Steinthal, Lazarus, etc.―but his philosophical and educational theories were widely discussed also in Italy, the United States (cf. Peirce, the Herbart-Society), and Japan. Based on contextualisation within post-Kantian philosophy and close text reading, Herbart’s relationships to Kant’s Critique of pure reason, his metaphysical realism, epistemological functionalism, and establishment of scientific psychology will be analysed. Pre-requisites: students should be familiar with the Kantian philosophy and German idealism. Course type: compulsory Lecturer: Nadia Moro (Assistant professor of philosophy) office hours: please check www.hse.ru/staff/nmoro contact details: Staraya Basmannaya Ul., 21/4, room 207; [email protected] Learning objectives During the course, students should: be introduced to the complexity of post-Kantian philosophy in the German area; gain knowledge of the main achievements of Herbart as a prominent post-Kantian philosopher; master the terminology of Herbart’s epistemology and theory of mind; develop skills in close reading, analysis, contextualisation, and critical evaluation of Herbart’s psychological and epistemological texts (cf. -

HERMANN COHEN and LEO STRAUSS Leora Batnitzky

JJTP_addnl_186-213 4/26/06 4:00 PM Page 187 HERMANN COHEN AND LEO STRAUSS Leora Batnitzky Princeton University Introduction Leo Strauss concluded both his first and last major works with ref- erence to Hermann Cohen.1 The arguments of Strauss’s first pub- lished book—Spinoza’s Critique of Religion—are rooted in Strauss’s initial work on Cohen’s interpretation of Spinoza. Strauss’s second book— Philosophy and Law—begins and ends by declaring that Cohen is right that the philosophy of Maimonides represents “true rationalism” and more particularly that Maimonides is better understood as a Platonist than as an Aristotelian. Strauss’s last published work, Studies in Platonic Political Philosophy, published posthumously, ends with an essay on Cohen, which was also the introduction to the English translation of Religion of Reason out of the Sources of Judaism. Interestingly, though this essay on Cohen is the final essay in Studies in Platonic Political Philosophy, it doesn’t have much to say about Plato. Although Strauss claims in this essay not have read Religion of Reason for forty years, those familiar with Strauss’s project will recognize that it is from an engagement with Cohen that Strauss forms his basic reading of Maimonides and then Plato. These readings changed in emphasis throughout Strauss’s career but they nevertheless remained funda- mental to his philosophical program. In this essay, I explore Strauss’s philosophical relation to Cohen. It is not an overstatement to suggest that Cohen is responsible for Leo Strauss’s turn to medieval Jewish philosophy. The focus of this essay, however, is not primarily on the details of Cohen and Strauss’s Presented at “Hermann Cohen’s Ethics,” the University of Toronto, August 2001. -

1 Thomas Meyer Leo Strauss's Religious Rhetoric

Thomas Meyer Leo Strauss’s Religious Rhetoric (1924-1938) Although he had been regarded as shy and restrained since his period of study in Marburg, Strauss was a master of religious rhetoric in his letters and [published] texts. This rhetoric was, for him, neither a [form of] compensation [for insufficient argument], nor a superficial adornment. On the contrary, he deployed religious rhetoric in same way that he analysed [its function] in Plato and Aristotle, through Maimonides and Abravanel, into Spinoza and Hobbes, and up to Hermann Cohen and Julius Guttmann: as an expression of the complex contest between philosophy and religion. After his engagement with Hermann Cohen’s critique of Spinoza in 1924, religious rhetoric was, for Strauss, no longer a feature of Zionist debates alone. Instead, it was a constitutive element of a problematic that Strauss strikingly and provocatively dubbed the “querelle des anciens et des modernes.” In order to understand this change in the function of religious rhetoric [in Strauss’ work], I shall consider three stations of Strauss’ intellectual development. First of all, I shall present several articles that I found in the “Jewish Weekly for Cassel, Hessen, and Waldeck”, which have remained unknown to scholarship until now. Strauss published these articles between February 1925 and January 1928. If we connect these texts with Strauss’s conclusions regarding Spinoza, we can develop a stable account of his religious rhetoric up to about 1934. But [Strauss’s use of religious rhetoric in these texts] can be understood only if we consider it in light of Strauss’ translation of a different religious rhetoric [into the terms of his own thought]: namely, the way Strauss enriched his religious rhetoric through an understanding of, and in dialogue with, the most radical position in Protestant [thought]—that of the dialectical theologian Friedrich Gogarten. -

The Philosophical Origins of Demythologizing

CHAPTER TWO THE PHILOSOPHICAL ORIGINS OF DEMYTHOLOGIZING: MARBURG NEO-KANTIANISM In the history of modern philosophy, Neo-Kantianism does not occupy a particularly significant role. 1 It most often appears as a transitional movement between nineteenth-century Kantian philos ophy and the phenomenology of Husserl and Heidegger. 2 As an historical phenomenon, Neo-Kantianism is sufficiently vague so that there is no clear agreement concerning the precise meaning of the term. M. Bochenski, for example, uses the term 'Neo-Kantian' to designate at least seven distinct schools of thought, including the materialist Hermann Helmholtz and the Neo-Hegelian Johannes Volkelt. 3 In its more technical, and frequent, usage however, the term is reserved for application to the two schools of Neo-Kantian ism in Germany at the turn of the century: the Marburg School and the Baden School. 4 The distinction between these two forms of Neo-Kantian philosophy is fundamental. While the Marburg School takes as its point of departure the exact sciences, more specifically pure mathematics and mathematical physics, the Baden School developed out of a concern with the social and historical siences. 5 1 For brief but helpful introductions to the central tenets of Neo-Kantian philosophy in the history of philosophy, see: a) W. Tudor Jones, Contemporary Thought of Germany (2 Vols.; London: Williams & Northgate Ltd., 1930), II, 30-75; b) John Theodore Merz, A History of European Thought in the Nineteenth Century (4 Vols.; Edinburgh: William Blanshard & Son, 1914); c) August Messer, Die Philosophie der Gegenwart (Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer, 1920), pp. l00 ff. 2 The significance of the writings of Paul Natorp for Husserl and Heidegger has been recognized, but, as yet, has not been systematically explored: J. -

Leibniz on Consciousness and Self-Consciousness Rocco J

Leibniz on Consciousness and Self-Consciousness Rocco J. Gennaro [Final version in NEW ESSAYS ON THE RATIONALISTS, Oxford U Press, 1999] In this paper I discuss the so-called "higher-order thought theory of consciousness" (the HOT theory) with special attention to how Leibnizian theses can help support it and how it can shed light on Leibniz's theory of perception, apperception, and consciousness. It will become clear how treating Leibniz as a HOT theorist can solve some of the problems he faced and some of the puzzles posed by commentators, e.g. animal mentality and the role of reason and memory in self-consciousness. I do not hold Leibniz's metaphysic of immaterial simple substances (i.e. monads), but even a contemporary materialist can learn a great deal from him. 1. What is the HOT Theory? In the absence of any plausible reductionist account of consciousness in nonmentalistic terms, the HOT theory says that the best explanation for what makes a mental state conscious is that it is accompanied by a thought (or awareness) that one is in that state.1 The sense of 'conscious state' I have in mind is the same as Nagel's sense, i.e. there is 'something it is like to be in that state' from a subjective or first-person point of view.2 Now, when the conscious mental state is a first-order world-directed state the HOT is not itself conscious; otherwise, circularity and an infinite regress would follow. Moreover, when the higher-order thought (HOT) is itself conscious, there is a yet higher-order (or third-order) thought directed at the second-order state. -

Against the Heteronomy of Halakhah: Hermann Cohen's Implicit Rejection of Kant's Critique of Judaism

Against the Heteronomy of Halakhah: Hermann Cohen’s Implicit Rejection of Kant’s Critique of Judaism George Y. Kohler* “Moses did not make religion a part of virtue, but he saw and ordained the virtues to be part of religion…” Josephus, Against Apion 2.17 Hermann Cohen (1842–1918) was arguably the only Jewish philosopher of modernity whose standing within the general philosophical developments of the West equals his enormous impact on Jewish thought. Cohen founded the influential Marburg school of Neo-Kantianism, the leading trend in German Kathederphilosophie in the second half of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth century. Marburg Neo-Kantianism cultivated an overtly ethical, that is, anti-Marxist, and anti-materialist socialism that for Cohen increasingly concurred with his philosophical reading of messianic Judaism. Cohen’s Jewish philosophical theology, elaborated during the last decades of his life, culminated in his famous Religion of Reason out of the Sources of Judaism, published posthumously in 1919.1 Here, Cohen translated his neo-Kantian philosophical position back into classical Jewish terms that he had extracted from Judaism with the help of the progressive line of thought running from * Bar-Ilan University, Department of Jewish Thought. 1 Hermann Cohen, Religion der Vernunft aus den Quellen des Judentums, first edition, Leipzig: Fock, 1919. I refer to the second edition, Frankfurt: Kaufmann, 1929. English translation by Simon Kaplan, Religion of Reason out of the Sources of Judaism (New York: Ungar, 1972). Henceforth this book will be referred to as RR, with reference to the English translation by Kaplan given after the German in square brackets. -

Herbart and Herbartianism in European Pedagogy: History and Modernity

Materials of International Scienti c and Practical Conference “PROFESSIONAL AND COMMUNICATION CULTURE OF THE FUTURE DOCTOR: LINGUISTIC, PEDAGOGICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL ASPECTS” УДК 371(091)(520) DOI 10.11603/me.2414-5998.2020.2.11143 N. O. Fedchyshyn¹ ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0909-4424 ResearcherID Q-5422-2016 Scopus Author ID 57202833382 Edvard Protner² Scopus Author ID 55749809900 ¹І. Horbachevsky Ternopil National Medical University ²University of Maribor, Slovenia HERBART AND HERBARTIANISM IN EUROPEAN PEDAGOGY: HISTORY AND MODERNITY Н. О. Федчишин¹, Едвард Протнер² ¹Тернопільський національний медичний університет імені І. Я. Горбачевського МОЗ України ²Маріборський університет, Словенія ГЕРБАРТ І ГЕРБАРТІАНСТВО В ЄВРОПЕЙСЬКІЙ ПЕДАГОГІЦІ: ІСТОРІЯ Й СУЧАСНІСТЬ Abstract. The proposed article offers an assessment of J.-F. Herbart and Herbartians in the history of pedagogy of Germany, pre- revolutionary Russia, and Ukraine; the in uence of the doctrine of J.-F. Herbart and Herbartians on the development of pedagogical science; borrowing ideas of these representatives in school education, namely the processes of formation, changes in directions, ideas, principles and tasks of the educational process; structural and substantive features of Herbartian pedagogy are revealed. It has been outlined the ways of popularizing Herbartianism in European countries and the signi cance of the theoretical heritage of Herbartians in the modern history of pedagogy. Key words: Herbartianism; J.-F. Herbart; pedagogical views; curriculum; theory and -

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer

03/05/2017 Arthur Schopenhauer (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer First published Mon May 12, 2003; substantive revision Sat Nov 19, 2011 Among 19th century philosophers, Arthur Schopenhauer was among the first to contend that at its core, the universe is not a rational place. Inspired by Plato and Kant, both of whom regarded the world as being more amenable to reason, Schopenhauer developed their philosophies into an instinctrecognizing and ultimately ascetic outlook, emphasizing that in the face of a world filled with endless strife, we ought to minimize our natural desires for the sake of achieving a more tranquil frame of mind and a disposition towards universal beneficence. Often considered to be a thoroughgoing pessimist, Schopenhauer in fact advocated ways — via artistic, moral and ascetic forms of awareness — to overcome a frustrationfilled and fundamentally painful human condition. Since his death in 1860, his philosophy has had a special attraction for those who wonder about life's meaning, along with those engaged in music, literature, and the visual arts. 1. Life: 1788–1860 2. The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason 3. Schopenhauer's Critique of Kant 4. The World as Will 5. Transcending the Human Conditions of Conflict 5.1 Aesthetic Perception as a Mode of Transcendence 5.2 Moral Awareness as a Mode of Transcendence 5.3 Asceticism and the Denial of the WilltoLive 6. Schopenhauer's Later Works 7. Critical Reflections 8. Schopenhauer's Influence Bibliography Academic Tools Other Internet Resources Related Entries 1. Life: 1788–1860 Exactly a month younger than the English Romantic poet, Lord Byron (1788–1824), who was born on January 22, 1788, Arthur Schopenhauer came into the world on February 22, 1788 in Danzig [Gdansk, Poland] — a city that had a long history in international trade as a member of the Hanseatic League. -

Einstein and the Development of Twentieth-Century Philosophy of Science

Einstein and the Development of Twentieth-Century Philosophy of Science Don Howard University of Notre Dame Introduction What is Albert Einstein’s place in the history of twentieth-century philosophy of science? Were one to consult the histories produced at mid-century from within the Vienna Circle and allied movements (e.g., von Mises 1938, 1939, Kraft 1950, Reichenbach 1951), then one would find, for the most part, two points of emphasis. First, Einstein was rightly remembered as the developer of the special and general theories of relativity, theories which, through their challenge to both scientific and philosophical orthodoxy made vivid the need for a new kind of empiricism (Schlick 1921) whereby one could defend the empirical integrity of the theory of relativity against challenges coming mainly from the defenders of Kant.1 Second, the special and general theories of relativity were wrongly cited as straightforwardly validating central tenets of the logical empiricist program, such as verificationism, and Einstein was wrongly represented as having, himself, explicitly endorsed those same philosophical principles. As we now know, logical empiricism was not the monolithic philosophical movement it was once taken to have been. Those associated with the movement disagreed deeply about fundamental issues concerning the structure and interpretation of scientific theories, as in the protocol sentence debate, and about the overall aims of the movement, as in the debate between the left and right wings of the Vienna Circle over the role of politics in science and philosophy.2 Along with such differences went subtle differences in the assessment of Einstein’s legacy to logical empiricism. -

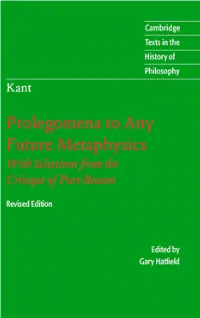

Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics CAMBRIDGE TEXTS in the HISTORY of PHILOSOPHY

CAMBRIDGE TEXTS IN THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY IMMANUEL KANT Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics CAMBRIDGE TEXTS IN THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY Series editors KARL AMERIKS Professor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame DESMOND M. CLARKE Professor of Philosophy at University College Cork The main objective of Cambridge Textsin the History of Philosophy is to expand the range, variety and quality of texts in the history of philosophy which are available in English. The series includes texts by familiar names (such as Descartes and Kant) and also by less well-known authors. Wherever possible, texts are published in complete and unabridged form, and translations are specially commissioned for the series. Each volume contains a critical introduction together with a guide to further reading and any necessary glossaries and textual apparatus. The volumes are designed for student use at undergraduate and postgraduate level and will be of interest not only to students of philosophy, but also to a wider audience of readers in the history of science, the history of theology and the history of ideas. For a list of titles published in the series, please see end of book. IMMANUEL KANT Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics That Will Be Able to Come Forward as Science with Selections from the Critique of Pure Reason TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY GARY HATFIELD University of Pennsylvania Revised Edition cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521828246 © Cambridge University Press 1997, 2004 This publication is in copyright. -

Lotze and the Early Cambridge Analytic Philosophy

LOTZE AND THE EARLY CAMBRIDGE ANALYTIC PHILOSOPHY ―This summer I‘ve read about a half of Lotze‘s Metaphysik. He is the most delectable, certainly, of all German writers—a pure genius.‖ William James, September 8, 1879.1 Summary Many historians of analytic philosophy consider the early philosophy of Moore, Russell and Wittgenstein as much more neo-Hegelian as once believed. At the same time, the authors who closely investigate Green, Bradley and Bosanquet find out that these have little in common with Hegel. The thesis advanced in this chapter is that what the British (ill-named) neo-Hegelians brought to the early analytic philosophers were, above all, some ideas of Lotze, not of Hegel. This is true regarding: (i) Lotze’s logical approach to practically all philosoph- ical problems; (ii) his treating of the concepts relation, structure (constructions) and order; (iii) the discussion of the concepts of states of affairs, multiple theory of judgment, general logical form; (iv) some common themes like panpsychism and contemplating the world sub specie aeternitatis. 1. LOTZE, NOT HEGEL, LIES AT THE BOTTOM OF CAMBRIDGE ANALYTIC PHILOSOPHY Conventional wisdom has it that the early philosophy of Moore and Russell was under the strong sway of the British ―neo-Hegelians‖. In the same time, however, those historians who investigate the British ―neo-Hegelians‖ of 1880–1920 in detail, turn attention to the fact that the latter are not necessarily connected with Hegel: William Sweet made this point in regard to 1 Perry (1935), ii, p. 16. Bosanquet,2 Geoffrey Thomas in regard to Green,3 and Peter Nicholson in regard to Bradley.4 Finally, Nicholas Griffin has shown that Russell from 1895–8, then an alleged neo-Hegelian, ―was very strongly influenced by Kant and hardly at all by Hegel‖.5 These facts are hardly surprising, if we keep in mind that the representatives of the school of T.