Trends in Tokyo's Office Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Certified Facilities (Cooking)

List of certified facilities (Cooking) Prefectures Name of Facility Category Municipalities name Location name Kasumigaseki restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Tokyo-club Building,3-2-6,Kasumigaseki,Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Sakura terrace,Iidabashi Grand Bloom,2-10- ALOHA TABLE iidabashi restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 2,Fujimi,Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku banquet kitchen The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 24th floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Peter The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Boutique & Café First basement, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Hei Fung Terrace The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Lobby 1-1-1,Uchisaiwai-cho,Chiyoda-ku TORAYA Imperial Hotel Store restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (Imperial Hotel of Tokyo,Main Building,Basement floor) mihashi First basement, First Avenu Tokyo Station,1-9-1 marunouchi, restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (First Avenu Tokyo Station Store) Chiyoda-ku PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Hot hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku Kitchen,Cold Kitchen) PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Preparation) hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku LE PORC DE VERSAILLES restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First~3rd floor, Florence Kudan, 1-2-7, Kudankita, Chiyoda-ku Kudanshita 8th floor, Yodobashi Akiba Building, 1-1, Kanda-hanaoka-cho, Grand Breton Café -

Introducing Tokyo Page 10 Panorama Views

Introducing Tokyo page 10 Panorama views: Tokyo from above 10 A Wonderful Catastrophe Ulf Meyer 34 The Informational World City Botond Bognar 42 Bunkyo-ku page 50 001 Saint Mary's Cathedral Kenzo Tange 002 Memorial Park for the Tokyo War Dead Takefumi Aida 003 Century Tower Norman Foster 004 Tokyo Dome Nikken Sekkei/Takenaka Corporation 005 Headquarters Building of the University of Tokyo Kenzo Tange 006 Technica House Takenaka Corporation 007 Tokyo Dome Hotel Kenzo Tange Chiyoda-ku page 56 008 DN Tower 21 Kevin Roche/John Dinkebo 009 Grand Prince Hotel Akasaka Kenzo Tange 010 Metro Tour/Edoken Office Building Atsushi Kitagawara 011 Athénée Français Takamasa Yoshizaka 012 National Theatre Hiroyuki Iwamoto 013 Imperial Theatre Yoshiro Taniguchi/Mitsubishi Architectural Office 014 National Showa Memorial Museum/Showa-kan Kiyonori Kikutake 015 Tokyo Marine and Fire Insurance Company Building Kunio Maekawa 016 Wacoal Building Kisho Kurokawa 017 Pacific Century Place Nikken Sekkei 018 National Museum for Modern Art Yoshiro Taniguchi 019 National Diet Library and Annex Kunio Maekawa 020 Mizuho Corporate Bank Building Togo Murano 021 AKS Building Takenaka Corporation 022 Nippon Budokan Mamoru Yamada 023 Nikken Sekkei Tokyo Building Nikken Sekkei 024 Koizumi Building Peter Eisenman/Kojiro Kitayama 025 Supreme Court Shinichi Okada 026 Iidabashi Subway Station Makoto Sei Watanabe 027 Mizuho Bank Head Office Building Yoshinobu Ashihara 028 Tokyo Sankei Building Takenaka Corporation 029 Palace Side Building Nikken Sekkei 030 Nissei Theatre and Administration Building for the Nihon Seimei-Insurance Co. Murano & Mori 031 55 Building, Hosei University Hiroshi Oe 032 Kasumigaseki Building Yamashita Sekkei 033 Mitsui Marine and Fire Insurance Building Nikken Sekkei 034 Tajima Building Michael Graves Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/1010431374 Chuo-ku page 74 035 Louis Vuitton Ginza Namiki Store Jun Aoki 036 Gucci Ginza James Carpenter 037 Daigaku Megane Building Atsushi Kitagawara 038 Yaesu Bookshop Kajima Design 039 The Japan P.E.N. -

MEGAMIASTO TOKIO RAJMUND MYDEŁ 7 Miast Świata (UN World Urbanization Prospect), Wyróżniana Jest Ta Nowa Kategoria Wielkościo Wa Miejskich Form Osadniczych

M EGAMI ASTO ТОКІО RAJMUND MYDEŁ Być małą kroplą w oceanie wiedzy, piękne marzenie Rajmund Mydeł M EGAMI ASTO ТОКІО RAJMUND MYDEŁ Kraków 2014 SPIS TREŚCI WPROWADZENIE............................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. PRZEDMIOT I CEL STUDIUM................................................................................................................................... 17 2 . KONCEPCJE PLANISTYCZNE ROZWOJU M EGAMI ASTA ORAZ PRZESTRZENNO-FUNKCJONALNE EFEKTY ICH REALIZACJI......................................................................................................................................... 29 3 . STRUKTURA WIELKOŚCIOWA MIAST ORAZ JEJ PRZESTRZENNE ZRÓŻNICOWANIE..........................lO l 4 . DEMOGRAFICZNO-SPOŁECZNY ORAZ FUNKCJONALNY OBRAZ M EGAMI ASTA I JEGO PRZESTRZENNA ZMIENNOŚĆ............................................................................................................... 121 5 . ROZWÓJ I PRZEMIANY PRZESTRZENNYCH UKŁADÓW RYNKU PRACY...................................................141 6. FUNKCJONOWANIE MEGAMIASTA ORAZ ZRÓŻNICOWANIE ŚRODKÓW TRANSPORTU W PRZEWOZACH PASAŻERSKICH.......................................................................................................................153 PODSUMOWANIE........................................................................................................................................................ 173 BIBLIOGRAFIA...............................................................................................................................................................177 -

Using JPF1 Format

FORUM State of the Art of Structural Control B. F. Spencer Jr. system is to reduce building vibration under strong winds and Nathan M. Newmark Professor, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engi- moderate earthquake excitations and consequently to increase neering, Univ. of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801. comfort of occupants of the building. E-mail: [email protected] Hybrid-control strategies have been investigated by many re- searchers to exploit their potential to increase the overall reliabil- S. Nagarajaiah ity and efficiency of the controlled structure ͑Housner et al. 1994; Associate Professor, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Rice Kareem et al. 1999; Nishitani and Inoue 2001; Yang and Dyke Univ., Houston, TX 77005. E-mail: [email protected] 2003; Casciati 2003; Faravelli and Spencer 2003͒. A hybrid- In recent years, considerable attention has been paid to research control system is typically defined as one that employs a combi- and development of structural control devices, with particular em- nation of passive and active devices. Because multiple control phasis on alleviation of wind and seismic response of buildings devices are operating, hybrid control systems can alleviate some of the restrictions and limitations that exist when each system is and bridges. In both areas, serious efforts have been undertaken in acting alone. Thus, higher levels of performance may be achiev- the last two decades to develop the structural control concept into able. Additionally, the resulting hybrid control system can be a workable technology. Full-scale implementation of active con- more reliable than a fully active system, although it is also often trol systems have been accomplished in several structures, mainly somewhat more complicated. -

Breaking the Rules of Kimono a New Book Shatters Antiquated Views of This Traditional Garment

JULY 2017 Japan’s number one English language magazine BREAKING THE RULES OF KIMONO A NEW BOOK SHATTERS ANTIQUATED VIEWS OF THIS TRADITIONAL GARMENT PLUS: The Boys for Sale in Shinjuku, Best Sake of 2017, Japan's New Emperor, and What Really Goes on Inside "Terrace House" To all investors and customers of e Parkhouse series: e Mitsubishi Jisho Residence overseas sales team is on hand for all your needs For the most up-to-date information about Mitsubishi Jisho Residence's new real estate projects, please visit our English website at www.mecsumai.com/international/en For inquiries, please email [email protected] Live in a Home for Life. e Parkhouse 34 26 32 36 JULY 2017 radar in-depth 36 BOYS FOR SALE THIS MONTH’S HEAD TURNERS COFFEE-BREAK READS A new documentary brings to light a particu- lar kind of sex trade in Shinjuku Ni-chome. 8 AREA GUIDE: YURAKUCHO 26 BREAKING THE RULES OF KIMONO This old-school neighborhood has a few A new book shows off the different person- modern surprises up its sleeve. alities of this very traditional garment. guide 14 STYLE 30 THE LIFE AND LOVE OF JAPAN'S CULTURE ROUNDUP Ready for a summer romance? Get your NEW EMPEROR 40 ART & FICTION spark back with some flirtatious swimwear As Emperor Akihito prepares to step down, Julian Lennon shows off his photography, all eyes are turning towards his son. and a new spy novel wends its way into 18 BEAUTY North Korea. Shake up your make-up with a full kit of 32 THE MISUNDERSTOOD CROWS organic, natural cosmetics. -

Shinjuku Park Tower : Access Map Park Hyatt Tokyo/Living Design Center Ozone/The Conran Shop Shinjuku/Park Tower Hall

SHINJUKU PARK TOWER : ACCESS MAP PARK HYATT TOKYO/LIVING DESIGN CENTER OZONE/THE CONRAN SHOP SHINJUKU/PARK TOWER HALL By train ● Tokyo Metro Marunouchi Line ● Toei Oedo Line ● JR Shinjuku Station 12 minutes walk Nishi-Shinjuku Station Shinjuku Nishiguchi Station ● Toei Shinjuku Line, Keio New Line Shinjuku Station 10 minutes walk Shinjuku I-LAND ● Keio New Line Hatsudai Station 8 minutes walk Shinjuku Nomura Bldg. Odakyu halc ● Toei Oedo Line Tochomae Station 8 minutes walk Hilton-Tokyo L-Tower Studio ALTA ● Odakyu Line Sangubashi Station 10 minutes walk Shinjuku Mitsui Bldg. Shuttle bus stop ● Kinokuniya Book Tokyo Metro Shinjuku Center Bldg. Isetan Sumitomo Bldg. Marunouchi Line Shinjuku Station Shinjuku Mitsukoshi ALCOTT Hyatt Regency Tokyo Shinjuku Station ●Tokyo Metro Marunouchi Line By bus ●Tokyo Metro Hukutoshin Line Kumano Jinjya Shinjuku Post Office ●JR line Shinjuku 3 Chome Station Keio Plaza Hotel ●Odakyu line By Keio Bus from JR Shinjuku Station (West Exit, No.21) "S01 Shinjuku Metropolitan ● Toei Oedo Line Keio Bus ●Keio line Otsuka furniture shop Loop" to Park Hyatt Tokyo A4 Tochomae Station Tokyo Metropolitan ■Shuttle Bus Service Juniso St. Shinjuku Central Park Main Building No.1 Shinjuku high school South Exit A shuttle bus service is available between SHINJUKU PARK TOWER and the Bank of Nishi-Shinjuku 1-Chome Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ on the first floor of the L Tower (Shinjuku Station West Exit) Shinjuku NS Bldg. (Shuttle buses leave every 10-15 minutes from 10:10a.m.) Shinjuku Central Park South KDDI Bldg. Koshu-Kaido Ave. ● Tokyo Metropolitan Toei Oedo Line Takashimaya Times Square Monday/Tuesday/Thursday 10:10~19:20 at interval of ten to fifteen minute Main Building No.2 ● Shinjuku Station Toei Shinjuku Line・ Friday/Saturday/Sunday 10:10~19:50 at interval of ten to fifteen minute Keio New Line Washington Hotel Shinjuku Station Wednesday 10:10~16:50 at interval of fifteen minute Nishi-Shinjuku Shuto Expressway Shinjukugyoen Tsunohazu kumin Shinjuku Ramp Center Mae Bunka Univ. -

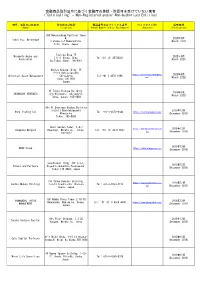

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered And/Or Non-Authorized Entities)

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered and/or Non-Authorized Entities) 商号、名称又は氏名等 所在地又は住所 電話番号又はファックス番号 ウェブサイトURL 掲載時期 (Name) (Location) (Phone Number and/or Fax Number) (Website) (Publication) 28F Nakanoshima Festival Tower W. 2020年3月 Tokai Fuji Brokerage 3 Chome-2-4 Nakanoshima. (March 2020) Kita. Osaka. Japan Toshida Bldg 7F Miyamoto Asuka and 2020年3月 1-6-11 Ginza, Chuo- Tel:+81 (3) 45720321 Associates (March 2021) ku,Tokyo,Japan. 104-0061 Hibiya Kokusai Bldg, 7F 2-2-3 Uchisaiwaicho https://universalassetmgmt.c 2020年3月 Universal Asset Management Chiyoda-ku Tel:+81 3 4578 1998 om/ (March 2022) Tokyo 100-0011 Japan 9F Tokyu Yotsuya Building, 2020年3月 SHINBASHI VENTURES 6-6 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku (March 2023) Tokyo, Japan, 102-0083 9th Fl Onarimon Odakyu Building 3-23-11 Nishishinbashi 2019年12月 Rock Trading Inc Tel: +81-3-4579-0344 https://rocktradinginc.com/ Minato-ku (December 2019) Tokyo, 105-0003 Izumi Garden Tower, 1-6-1 https://thompsonmergers.co 2019年12月 Thompson Mergers Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Tel: +81 (3) 4578 0657 m/ (December 2019) 106-6012 2019年12月 SBAV Group https://www.sbavgroup.com (December 2019) Sunshine60 Bldg. 42F 3-1-1, 2019年12月 Hikaro and Partners Higashi-ikebukuro Toshima-ku, (December 2019) Tokyo 170-6042, Japan 31F Osaka Kokusai Building, https://www.smhpartners.co 2019年12月 Sendai Mubuki Holdings 2-3-13 Azuchi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tel: +81-6-4560-4410 m/ (December 2019) Osaka, Japan. 16F Namba Parks Tower 2-10-70 YAMANASHI KYOTO 2019年12月 Nanbanaka, Naniwa-ku, Osaka, Tel: +81 (0) 6-4560-4440 https://www.ykmglobal.com/ MANAGEMENT (December 2019) Japan 8th Floor Shidome, 1.2.20 2019年12月 Tenshi Venture Capital Kaigan, Minatu-ku, Tokyo (December 2019) 6flr Nishi Bldg. -

Tallest Buildings Constructed in 1970-1980

This PDF was downloaded from The Skyscraper Center on 2018/01/11 UTC For the most up to date version, please visit http://skyscrapercenter.com Building List All Regions, All Companies, 200m+, 1970-1980 Completed Architecturally Topped Structurally Topped Under On Never Proposed Vision Demolished Out Out Construction Hold Completed # Building Name City Height (m) Height (ft) Floors Completed Material Use 1 Willis Tower Chicago 442.1 1,451 108 1974 steel office 2 Aon Center Chicago 346.3 1,136 83 1973 steel office 3 First Canadian Place Toronto 298.1 978 72 1975 steel office 4 601 Lexington New York City 278.9 915 63 1977 steel office 5 Water Tower Place Chicago 261.9 859 74 1976 concrete residential / hotel / retail 6 Aon Center Los Angeles 261.5 858 62 1974 steel office 7 Transamerica Pyramid Center San Francisco 260 853 48 1972 composite office 8 U.S. Steel Tower Pittsburgh 256.3 841 64 1970 steel office 9 IDS Center Minneapolis 241.4 792 55 1973 composite office 10 200 Clarendon Boston 240.8 790 62 1976 steel office 11 Sunshine 60 Tower Tokyo 240 787 60 1978 composite office 12 Commerce Court West Toronto 239 784 57 1973 composite office 13 Enterprise Plaza Houston 230.4 756 55 1980 composite office 14 One Penn Plaza New York City 228.6 750 57 1972 steel office 15 1251 Avenue of the Americas New York City 228.6 750 54 1972 steel office 16 MLC Centre Sydney 228 748 60 1977 concrete office 17 One Astor Plaza New York City 227.1 745 54 1972 composite office 18 One Liberty Plaza New York City 226.5 743 54 1972 steel office 19 Parque Central -

Semi-Annual Report

Tenth Fiscal Period Semi-Annual Report May 1, 2008 October 31, 2008 Profile Nomura Real Estate Office Fund, Inc. (referred to as “Nomura Office Fund” or the “Company” hereafter) was listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange on December 4, 2003 as a real estate investment corporation formed to own and invest in office properties, subject to the Law Concerning Investment Trusts and Investment Corporations of Japan. The Company’s basic investment policy is to assure stable rent revenues and steady portfolio growth over the medium- to long-term. Nomura Real Estate Asset Management Co., Ltd. (referred to as “NREAM” hereafter), a wholly owned subsidiary of Nomura Real Estate Holdings, Inc. is in charge of asset management on behalf of Nomura Office Fund in accordance with the basic investment policy as described above. Through coordination with Nomura Real Estate Holdings, Inc. and other group companies, NREAM aims to achieve these goals and more. Strength of Nomura Office Fund J-REIT with a large-capitalization specialized in office buildings ■ Portfolio of 46 properties at a total acquisition price of ¥362.2 billion (as of October 31, 2008) ■ Market capitalization of ¥168.1 billion (as of October 31, 2008) ■ Constituent of MSCI Standard Index Track records of stable managements ■ Ten consecutive fiscal periods of growth in operating revenues and net income ■ Steady growth in DPU Collaboration with Nomura Real Estate Group ■ NREAM, in charge of the Company’s asset management, belongs to Nomura Real Estate Group ■ Supported by the group companies through provision of sales information and management expertise Rated A or more by three domestic and foreign rating agencies Rating and Investment Information, Inc. -

Corporate History 1800S in 2009, Kajima Corporation Celebrated Its 170Th Anniversary

CORPORATE HISTORY 1800s IN 2009, KAJIMA CORPORATION CELEBRATED ITS 170TH ANNIVERSARY. From the historic Edo period to today, Kajima has played a vital role in developing the social capital essential to 1860 Ei-Ichiban Kan Japan’s industrial and eco- 1880 Began construction of Yanagase nomic advancement, and an Railroad improved standard of living for Iwazo Kajima its citizens. Naturally, times [JAPAN] have not always been generous, and countless chal- 1860 Ei-Ichiban Kan lenges have arisen over the years. To face them, our 1872 Houraisha Office predecessors pooled their knowledge and strengths 1874 Papermaking Company (Oji to anticipate the needs of the era, turning the tables Paper) Factory on adversity to embark on a bold wave of manage- 1878 Okayama Prefectural Office 1880 Began construction of ment innovation. Yanagase Railroad 1872 Houraisha Office The key to Kajima’s ongoing development is a bold 1891 Began construction of Usui and vigorous enterprising spirit that runs through the Railway Line veins of our managers and employees. Our corporate philosophy is “As a group of individuals working together as one, we pursue creative progress and development founded on both rational, scientific 1874 Papermaking Company (Oji Paper) principles and a humanitarian outlook, through which Factory we strive to continually advance our business operations and con- tribute to society.” While times may change, our unyield- 1878 Okayama Prefectural Office ing commitment to this philosophy never will. [OVERSEAS] 1899 Built railroads in Taiwan, Korea, etc. 1899 Built railroads in Taiwan, Korea, etc. 82 KAJIMA CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2011 1900-1959 1960-1969 1918 Began construction of 1963 New Tanna Tunnel Tanna Tunnel (17-year project) 1924 Ohmine Dam 1968 Kasumigaseki Building 1918 Began construction of 1960 Yamashina construction Tanna Tunnel (17-year zone on the Meishin project) Expressway 1924 Ohmine Dam 1961 Okutadami Dam 1934 Ueno Station 1962 Tobata Iron Mill, Yawata Iron 1957 No.1 Reactor, Japan Nuclear and Steel Co., Ltd. -

Explore Our 160 Premium Locations Around the World

120. Explore our 160 premium locations around the world. We have selected the finest locations around the globe to help the growth of your business and to ensure an impressive experience for your clients. Australia Bahrain France Adelaide Manama Paris Westpac House Bahrain Financial Harbour Haussmann - Opéra Brisbane Diplomatic Commercial Tower Eagle Street Germany Santos Place Belgium Berlin Canberra Brussels Potsdamer Platz Nishi Building Bastion Tower The Realm Schuman India Hobart Mumbai Reserve Bank Building China Vibgyor Towers Melbourne Beijing Hyderbad 101 Collins Street China Central Place Mindspace Complex 140 William Street Fortune Financial Center Southbank Riverside Quay Oriental Plaza Indonesia Perth Chengdu Jakarta Brookfield Place Shangri-La Office Tower International Financial Centre AMP Tower Guangzhou Sydney International Finance Center Japan Avaya House Hangzhou Barangaroo Tower One Fukuoka JIAHUA International Business Fukuoka Tenjin Fukoku Seimei Chifley Tower Center Deloitte Building Building Shanghai NMF Hakata Ekimae Building Gateway Citigroup Tower 44 Market Street Osaka Jing An Kerry Center Edobori Center Building 101 Miller Street Hong Kong MLC Centre Hilton Plaza West Tower One Peking Road Shinsaibashi Plaza Building Nexus Norwest The Hong Kong Club Building Octagon Building Two International Finance Centre Westfield Tower Japan (continued) Qatar United Kingdom Nagoya Doha London Honmachi Minami Garden City Commercial Bank Plaza Canary Wharf Nagoya Lucent Tower Doha Tower Dashwood House Nagoya Nikko Shoken -

Health Checkup and Cancer Screening Handbook

2021 新宿区 Health Checkup and Cancer Screening Handbook Health Checkup Eligible person Residents aged 16 and older However, residents aged 40 to 74 are limited to those who are National p1~ Health Insurance members or those who receive the Public Assistance, etc. Cost No fee ※ Ifyouwillhaveacomprehensivemedicalexaminationorabusinessowner'smedicalexamination, pleasereferpage8ofthispamphlet(ShinjukuCityNationalHealthInsurancemember) Cancer Screening Eligible person Shinjuku City residents. p3~ The screenings that can be taken vary depending on the age. Cost Paid service( there is a fee exemption program) ~ Hepatitis Virus Screening p7 Eligible person Shinjuku City residents who are aged 40 and older and have never been screened for hepatitis virus. Cost No fee p25~ Dental Health Checkup Other information Medical Notebook Flow of Health Checkup 1 2 3 Select a medical institution Take a medical examination with a Make sure that you have a required health (P11~) health checkup form or checkup form or cancer screening form cancer screening form ※ You cannot receive a medical examination without the required health checkup form/cancer screening form. ※If you want to use the cancer screening cost exemption program, you need to apply prior the procedure ③ (P6). 健康診査・がん検診の外国語版案内( 英語・中国語・韓国語) があります。 / 健康づくり課健診係 ☎03(5273)4207( 日本語対応 ) でご連絡ください。 There are foreign language guide pamphlets in English, Chinese or Korean for Health Checkup and Cancer Screening. / Please contact Health Promotion Division Health Checkup Section ☎ 03 (5273) 4207 (in Japanese). ☎ 健康检查、癌症筛查的外语版指南小册子(英文,中文,韩文)可直接与。/健康促进课健诊系联系。 03(5273)4207(日语受理) ☎ 건강진단・암 검진의 외국어판 안내책자(영어・중국어・한국어)의 청구처/건강추진과 검진계 03(5273)4207(일본어 대응) 令和 3 年4月発行 You can have a Health Checkup once a year No medical certificate Precautions before going to a health checkup ( No fee) will be issued.