Sudan Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Risk for Boys from Poor Communities to Drop out from School: the Case of Khartoum, Sudan

Yousif & Mohammed. Space and Culture, India 2020, 8:1 Page | 187 https://doi.org/10.20896/saci.v8i1.711 RESEARCH OPEN ACCESS The Risk for Boys from Poor Communities to Drop out from School: The Case of Khartoum, Sudan Nagwa Babiker Abdalla Yousif†* and Shadia Abdel Rahim Mohammed¥ Abstract In the current world, poverty and education are interconnected. Low level of education is the cause of poverty, as extreme forms of poverty do not allow many children to get a good education. This study investigates the risk factors that significantly increase the likelihood of pupils dropping out of school in Khartoum, Sudan. To accomplish the research, two factors are selected, namely absenteeism and low performance of pupils from poor, disadvantaged communities. A comprehensive interviewing is used to collect the necessary primary data along with the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) data. The life of pupils is characterised by multi-dimensional poverty apace with illiteracy, displacement and large family size, parents' engagement in low paid jobs. The pupils presented multiple reasons (related to poverty) for their absenteeism and low performance. The results indicate that pupils are not clear with their future perspectives whether to drop out of the school or to continue their studies. The study concludes that poverty is the main reason for absenteeism and low performance that increases the likelihood of pupils dropping out of school. Keywords: School Education; Poor Communities; Absenteeism; Migration; Performance; Sudan †Assistant Professor, College of Humanities and Sciences, Department of Sociology, Ajman University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates * Corresponding Author, Email: [email protected]; [email protected] ¥Professor, School of Rural Extension Education and Development, Ahfad University for women, Omdurman, Sudan. -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

Migrants in Need of Protection

A report of the Scalabrini migration study centers The Scalabrini migration study centers consist of the Centro de Estudios Migratorios (CEM) in Brazil, the Centro de Estudios Migratorios Latinoamericanos (CEMLA) in Argentina, the Centre d’Information et d’Études sur les Migrations Internationales (CIEMI) in France, the Center for Migration Studies of New York (CMS) in the United States, the Centro Studi Emigrazione Roma (CSER) in Italy, the Scalabrini Institute for Human Mobility in Africa (SIHMA) in South Africa, the Scalabrini International Migration Network (SIMN) in the United States, and the Scalabrini Migration Center (SMC) in the Philippines. This report was edited by J. Kevin Appleby, Senior Director for International Migration Policy for CMS and SIMN, and by Donald Kerwin, Executive Director of CMS. The editors would like to thank Fr. Leonir Chiarello, c.s., Executive Director of SIMN, for his leadership and support during the process. Published by the Center for Migration Studies of New York (CMS) 307 E 60th St., 4th Floor, New York, NY 10022 www.cmsny.org Cover Photo: Alun McDonald/Oxfam, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 “A boy walks home to camp Jamam, South Sudan.” International Migration Policy Report: Responsibility Sharing for Large Movements of Refugees and Migrants in Need of Protection A report of the Scalabrini migration study centers June 2017 Asia | Africa | Europe Latin America | North America International Migration Policy Report June 2017 Table of Contents 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................1 -

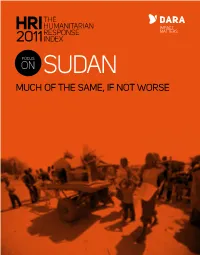

FOCUS on SUDAN Report

THE HUMANITARIAN HRIRESPONSE 2011INDEX FOCUS ON SUDAN MUCH OF THE SAME, IF NOT WORSE CRISIS AT A GLANCE SUDAN 66,000 internally 300,000 internally displaced or severely displaced or severely affected people (out of a affected people (from a total of 200,000 affected 1.9 million people in total of 1 million affected by fighting) to South 153,000 refugees IDP camps in Darfur by fighting) Sudan from Sudan. in Sudan LIBYA Red Sea Northern Access extremely restricted/denied North Nile Access possible but within restrictions Darfur Non-priority area for humanitarian response IDP and refugee returns SUDAN Kassala ERITREA CHAD KHARTOUM People newly displaced in 2011 16,000 35,000 Number of Southerners in transit or who have North Kordofan returned to South Sudan 15,000 12,000 Population movements Gedaref West White Major fighting in 2011 Darfur Sennar 80,000 Nile 45,000 Source: OCHA, UNHCR, Natural Earth, USGS South South Blue Darfur Kordofan Nile 37,000 ETHIOPIA CENTRAL 30,000 AFRICAN 20,000 REPUBLIC 110,000 357,000 SOUTH SUDAN Warrap TOTAL FUNDING TO SUDAN IN 2010: 468,000 new internally displaced persons (IDPs) US$ 1.4 BILLION and refugees have been created in the past year due to the ongoing violence in the border states of Blue Nile and South Kordofan. These new IDPs 74 % INSIDE THE CAP and refugees are supplementary to the 110, 000 refugees in South Sudan from the oil-rich region of Abyei. Meanwhile, 1.9 million people still reside in THE CRISIS AND THE camps in Darfur. RESPONSE Humanitarian access in some areas of Darfur and The Republic of South Sudan was born on 9 July of South Kordofan is denied by the Sudanese Armed 2011 in a context of instability due to increased fighting Forces, leaving hundreds of thousands of civilians between the Sudanese Army and the Sudan People's without assistance. -

Mahdism and Islamism in Sudan Author(S): Gabriel Warburg Reviewed Work(S): Source: International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol

Mahdism and Islamism in Sudan Author(s): Gabriel Warburg Reviewed work(s): Source: International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 27, No. 2 (May, 1995), pp. 219-236 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/176093 . Accessed: 19/11/2012 19:55 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of Middle East Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.82.207 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 19:55:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Int. J. Middle East Stud. 27 (1995), 219-236. Printed in the United States of America Gabriel Warburg MAHDISM AND ISLAMISM IN SUDAN On 30 June 1989, a military coup overthrew the democratically elected government of al-Sadiq al-Mahdi in Sudan and replaced it with a fundamentalist Muslim dictatorship headed by Colonel CUmarHasan al-Bashir and adhering to the radical Islamic ideology of the National Islamic Front (NIF), under the leadership of Dr. Hasan al-Turabi. Since June 1881 when Muhammad Ahmad ibn 'Abdallah declared that he was the expected mahdi, the religious-political scene of Sudan had been largely dominated by Mahdists and Khatmiyya adherents. -

'Adaptive Learning' in the Case of China- Sudan and South

The London School of Economics and Political Science Chinese Foreign Policy in the ‘Going Out’ Era: Confronting Challenges and ‘Adaptive Learning’ in the Case of China- Sudan and South Sudan Relations Laura Barber A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, June 2014 1 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 97,667 words. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to understand change within China’s foreign policy under a ‘Going Out’ strategy in Sudan and South Sudan between 1993 and 2013. China has traditionally viewed the Sudanese and African context more generally as having a wholly positive impact on its interests. However, in the Sudan case, the insertion of China’s leading National Oil Company into the Sudanese political economy from the mid-1990s has meant that Sudan’s internal situation has negatively affected China’s interests and, in turn, impacted on its foreign policy. -

Sudan and South Sudan

2011_CIC_2.qxd:Peacekeeping_FM_qxd.qxd 1/16/12 1:44 PM Page 69 2.6 Sudan and South Sudan Sudan and South Sudan, which together over eligibility to participate in its referendum. host nearly one-third of the UN’s total global In response to the violence and in the context troop deployment, experienced profound and of an agreement by the parties on temporary dramatic changes in 2011 and remain among arrangements for the security and administra- the most challenging theaters for UN peace tion of Abyei, the Security Council authorized operations. In 2011 an increasingly complex deployment of the UN Interim Security Force and diverse architecture for UN operations for Abyei (UNISFA) in June 2011. emerged, involving three separate peacekeep- There has also been a deterioration of ing missions and numerous political processes. conditions in areas of the north covered by The secession of Sudan’s southern region the CPA—the Southern Kordofan State and as the Republic of South Sudan is a historical the Blue Nile State—with the eruption of se- and structural political transformation with vere hostilities between the Sudan Armed significant implications for UN peace opera- Forces (SAF) and northern units of the Sudan tions. The January 2011 referendum proceeded People’s Liberation Army that may portend a peacefully, with substantial operational sup- return to protracted civil conflict. Coinciding port from the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS), with the conclusion of the UNMIS mandate, with southerners voting overwhelmingly for this outbreak of violence presented serious - independence. South Sudan’s procession to independence on 9 July 2011 was marked by notable political compromise and restraint by both Juba and Khartoum and concerted third- party engagement from the African Union, the UN, and key members of the international community. -

Rohingyas: the People for Whom No One Is Responsible

A report of the Scalabrini migration study centers The Scalabrini migration study centers consist of the Centro de Estudios Migratorios (CEM) in Brazil, the Centro de Estudios Migratorios Latinoamericanos (CEMLA) in Argentina, the Centre d’Information et d’Études sur les Migrations Internationales (CIEMI) in France, the Center for Migration Studies of New York (CMS) in the United States, the Centro Studi Emigrazione Roma (CSER) in Italy, the Scalabrini Institute for Human Mobility in Africa (SIHMA) in South Africa, the Scalabrini International Migration Network (SIMN) in the United States, and the Scalabrini Migration Center (SMC) in the Philippines. This report was edited by J. Kevin Appleby, senior director for international migration policy for CMS and SIMN, and by Donald Kerwin, executive director of CMS. The editors would like to thank Fr. Leonir Chiarello, c.s., executive director of SIMN, for his leadership and support during the process. Published by the Center for Migration Studies of New York (CMS) 307 E 60th St., 4th Floor, New York, NY 10022 www.cmsny.org Cover Photo: Alun McDonald/Oxfam, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 “A boy walks home to camp Jamam, South Sudan.” International Migration Policy Report: Responsibility Sharing for Large Movements of Refugees and Migrants in Need of Protection A report of the Scalabrini migration study centers June 2017 Asia | Africa | Europe Latin America | North America International Migration Policy Report June 2017 Table of Contents 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................1 -

The Sudans: Which Way?

BULLETIN N°86 – NOVEMBER 2011 http://concernedafricascholars.org The Sudans: Which Way? Association of Concerned Africa Scholars ACAS Association of Concerned Africa Scholars The Sudans: Which Way? BULLETIN N°86 – NOVEMBER 2011 Table of Contents Introduction Horace Campbell and Peter Limb, Issue editors 1-3 The Republic of South Sudan and the Meaning of Independence Horace Campbell 4-10 Citizenship and Identity in Post-Secession Northern Sudan Ahmad A. Sikainga 11-19 Gendering War and Peace in South Sudan: The Elision and Emergence of Women Caroline Faria 20-29 Genealogies of Racial Relations: The Independence of South Sudan, Citizenship & the Racial State in the Modern History of Sudan Elena Vezzadini 30-46 The State of South Sudan: The Change is about the New Sudan Abdullahi Gallab 47-53 South Sudan Looks East: Between the CPA and Independence Daniel Large 54-58 On cover: Photo of independence, South Sudan, July 2011, courtesy of Caroline Faria ACAS Bulletin #86 – The Sudans: Which Way? Introduction Horace Campbell and Peter Limb South Sudan became a member of the African being stuck in old paradigms without an Union and the 193rd member of United Nations after understanding of the changing political environment it gained its independence on July 9, 2011. The new in Africa. Because of its own myopia on the situation in the Sudan and in Africa was a real test question of minority rights, the government of the for rethinking old categories in politics. Peoples Republic of China had adopted a formula for engagement with the Sudan that privileged the In this issue of the ACAS Bulletin, the editors bring Bashir National Congress Party (NCP) regime in six different perspectives on the possible paths for Khartoum. -

I. the Informal Economy

2016 2016 Report Team Background and Regional Papers: Ziad Abdel Samad (Executive Director, Arab NGO Network for Development), Roberto Bissio (Coordinator, Social Watch In- ternational Secretariat), Samir Aita (President, Cercle des Economistes Arabes), Dr. Martha Chen and Jenna Harvey (WIEGO Network), Dr. Mohamed Said Saadi (Political Economy Professor and Researcher), Dr. Faouzi Boukhriss (Sociology Professor, Ibn Toufail University, Qunaitira, Morocco), Dr. Howaida Adly (Political Sciences Professor, National Center for Sociological and Criminilogical Research, Egypt), Dr. Azzam Mahjoub (University Professor and International Expert), ANND works in 12 Arab countries with 9 national networks (with an extended membership Mohamed Mondher Belghith (International Expert), Shahir George (Independent of 250 CSOs from different backgrounds) and 23 NGO members. Researcher). P.O.Box: 4792/14 | Mazraa: 1105-2070 | Beirut, Lebanon National Reports: Dr. Moundir Alassasi (Job Market and Social Protection in the Tel: +961 1 319366 | Fax: +961 1 815636 Arab World Researcher and Expert), Dr. Khaled Minna (Job Market Researcher and www.annd.org – www.csrdar.org Expert), Dr. Hassan Ali al-Ali (Independent Researcher, Bahrain), Dr. Reem Adbel Halim (Independent Researcher, Egypt), Saoud Omar (Unionist and Consultant to the International Industrial Union, Egypt), Hanaa Abdul Jabbar Saleh (National Accounts Expert, Iraq), Ahmad Awad (Phenix Center for Economic and Informat- ics Studies, Jordan), Rabih Fakhri (Independent Researcher, Lebanon), Moham- med Ahmad al-Mahboubi (Development, Media, and Gender Studies Expert and Consultant, Mauritania), Dr. Faouzi Boukhriss (Sociology Professor, Ibn Toufail University, Qunaitira, Morocco), Firas Jaber (Founder and Researcher, al-Marsad, Palestine), Iyad Riyahi (Founder and Researcher, al-Marsad, Palestine), Dr. Hassan Ahmad Abdel Ati (National Civil Forum, Sudan), Dr. -

Downloads/Reports/ Department of State

U4 Expert Answer Sudan: Overview of corruption and anti-corruption Query Please provide an overview of the nature and impact of corruption in Sudan including extent, nature, sectors most affected (extractive industries, public financial management, police and security), anti-corruption efforts, and legal and institutional framework (including judiciary). We are also interested in the following areas: public administration at national, regional and local levels, health, agriculture, natural resources and the environment. Content Sudan is, without a doubt, one of the most challenging environments for anti-corruption in the 1. Overview of corruption in Sudan world. Corruption is present in all sectors and 2. Corruption by sector across all branches and levels of government: public servants are known to demand bribes for 3. Legal and institutional anti-corruption services that individuals or companies are legally frameworks entitled to; government officials hold direct and 4. Anti-Corruption entry points for highly corrupt indirect stakes in many enterprises, which distorts environments the market through patronage and cronyism; and 5. References the head of state and government is believed to have embezzled up to US$9 billion from oil Caveat revenues. Due to a lack of information, not all the sectors This U4 Expert Answer provides a general requested by the enquirer could be included in the overview of the nature and extent of corruption in answer. Providing policy advice is beyond the the country, the state of its legal and institutional scope of the Helpdesk, for that reason, the last framework to prevent it, as well as its presence section of this document simply summarizes across different sectors of the economy. -

![Égypte/Monde Arabe, 14 | 2016, « Le Soudan, Cinq Ans Après L’Indépendance Du Soudan Du Sud » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 21 Octobre 2018, Consulté Le 06 Novembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3189/%C3%A9gypte-monde-arabe-14-2016-%C2%AB-le-soudan-cinq-ans-apr%C3%A8s-l-ind%C3%A9pendance-du-soudan-du-sud-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-21-octobre-2018-consult%C3%A9-le-06-novembre-2020-6033189.webp)

Égypte/Monde Arabe, 14 | 2016, « Le Soudan, Cinq Ans Après L’Indépendance Du Soudan Du Sud » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 21 Octobre 2018, Consulté Le 06 Novembre 2020

Égypte/Monde arabe 14 | 2016 Le Soudan, cinq ans après l’indépendance du Soudan du Sud Alice Franck et Elena Vezzadini (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ema/3560 DOI : 10.4000/ema.3560 ISSN : 2090-7273 Éditeur CEDEJ - Centre d’études et de documentation économiques juridiques et sociales Édition imprimée Date de publication : 21 octobre 2016 ISBN : 2-905838-88-4 ISSN : 1110-5097 Référence électronique Alice Franck et Elena Vezzadini (dir.), Égypte/Monde arabe, 14 | 2016, « Le Soudan, cinq ans après l’indépendance du Soudan du Sud » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 21 octobre 2018, consulté le 06 novembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ema/3560 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ema. 3560 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 6 novembre 2020. © Tous droits réservés 1 Le Soudan du Sud a accédé officiellement à l’indépendance le 9 juillet 2011, à l’issue d’un processus de paix acté en janvier 2005 et conformément au résultat du référendum national de janvier 2011. Cet événement historique qui devait clore une page de l’histoire conflictuelle entre les régions et communautés soudanaises du Nord et du Sud a constitué un réel défi en termes d’adaptation, de résilience et d’innovation pour l’ensemble de la société. Dans ce contexte inédit de naissance d’un nouveau territoire national, et de remodelage des configurations spatiales et politiques existantes, le Soudan du Sud a été très logiquement au centre des attentions – qu’il s’agisse des acteurs politiques, des chercheurs ou des bailleurs humanitaires. Pourtant, le Nord a été aussi profondément affecté par cette rupture.