Management | Review |

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POLSKA STOLICA WIKLINY W Rudniku Nad Sanem Widać, ¿E

W Rudniku nad Sanem widaæ, ¿e „Polska Piêknieje” „POLAND IS GETTING MORE BEAUTIFUL” IN RUDNIK ON THE SAN POLSKA STOLICA WIKLINY THE POLISH CAPITAL OF WICKERWORK THE POLISH CAPITAL OF WICKERWORK POLSKA STOLICA WIKLINY CENTRUM WIKLINIARSTWA POLSKA STOLICA WIKLINY LAUREAT I EDYCJI KONKURSU RUDNIK NAD SANEM POLSKA PIÊKNIEJE – 7 CUDÓW UNIJNYCH FUNDUSZY RUDNIK ON THE SAN WICKERWORK CENTRE THE POLISH CAPITAL LAUREATE OF 1ST EDITION OF THE COMPETITION OF WICKERWORK Centrum Wikliniarstwa „POLAND IS GETTING MORE BEAUTIFUL. 7 MARVELS OF EUROPEAN FUNDS” W Rudniku nad Sanem widaæ, ¿e „Polska Piêknieje” „POLAND IS GETTING MORE BEAUTIFUL” IN RUDNIK ON THE SAN MIEJSKI OŒRODEK KULTURY W RUDNIKU NAD SANEM, 2010 MUNICIPAL CULTURE CENTRE IN RUDNIK ON THE SAN, 2010 Pere³ka na mapie Polski i Podkarpacia – Rudnik nad Sanem – siedmiotysiêczne mia- steczko rokrocznie zachwyca nowymi cudami z wikliny. 140-letnie tradycje koszykar- Rudnik on the San, a real skie miasto zawdziêcza w³aœci- pearl on the map of Poland and cielowi dóbr rudnickich, hrabie- the Subcarpathian region, is a mu Ferdynandowi Hompescho- town with seven thousand inha- wi, który pozosta³ we wdziêcz- bitants which enchants with new nej pamiêci mieszkañców wikli- wicker marvels every year. nowego grodu. The 140 year old basket-ma- king traditions of the town are attributed to the owner of Rud- nik estate, Count Ferdinand Hompesch, dearly remembered by the inhabitants of this wicker town. 2 Pomnik hr. Ferdynanda Hompescha na rudnickich plantach The Monument of Count Ferdinand Hompesch in the Rudnik municipal park Tylko tutaj zwiedziæ mo¿e- my jedyne w kraju Centrum Wikliniarstwa – instytucjê wysta- wienniczo-edukacyjn¹, zaskaku- j¹c¹ pomys³owymi ekspozycjami wikliny u¿ytkowej i artystycznej. -

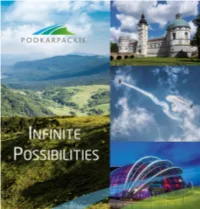

Podkarpackie-En-2016.Pdf

Rzeszów 2016 Acrobatics in the sky PODKARPACKIE during the Podkarpackie Air Show. (MM) – INFINITE POSSIBILITIES The Region of Podkarpackie – a gateway to the European Union, land comprises an area of 18,000 km2 and has a population of over of modern economy, unpolluted natural environment, wealth of cul- 2 million. Its neighbours include Slovakia in the south, and Ukraine in ture, and... opportunities. Here, innovative technologies of aerospace, the east - across the external border of the European Union. This is also information and automotive industries come side by side with active the cross-roads for the trading routes of Central Europe. The motorway leisure, mountain adventures, multiculturalism and creativity. Interna- linking Western and Eastern Europe, Via Carpathia designed to con- tional airport, EU border crossings, East-West motorway, areas desig- nect North and South in the future, as well as the modern airport with nated for investments and resources of well-educated young people international passenger and cargo terminals are the reason why are the reasons why global companies bring their business here. And operations of numerous manufacturing, trading and logistics compa- after work? Anything goes! From the atmosphere of urban cafeterias, nies are located here. The region’s capital with a population of nearly pubs, theatres, and concerts, to recreation activities on the ground, on 200,000, Rzeszów is a vibrant, youthful and modern city, one of the the water and in the air, amidst wildlife, Carpathian landscapes, and most rapidly growing urban agglomerations in Poland. This is also home legends of the Bieszczady and Beskid Niski. On top of that, one can to the Aviation Valley. -

Official Journal L277

Official Journal L 277 of the European Union Volume 64 English edition Legislation 2 August 2021 Contents II Non-legislative acts REGULATIONS ★ Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/1253 of 21 April 2021 amending Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/565 as regards the integration of sustainability factors, risks and preferences into certain organisational requirements and operating conditions for investment firms (1) . 1 ★ Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/1254 of 21 April 2021 correcting Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/565 supplementing Directive 2014/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards organisational requirements and operating conditions for investment firms and defined terms for the purposes of that Directive (1) . 6 ★ Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/1255 of 21 April 2021 amending Delegated Regulation (EU) No 231/2013 as regards the sustainability risks and sustainability factors to be taken into account by Alternative Investment Fund Managers (1) . 11 ★ Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/1256 of 21 April 2021 amending Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35 as regards the integration of sustainability risks in the governance of insurance and reinsurance undertakings (1) . 14 ★ Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/1257 of 21 April 2021 amending Delegated Regulations (EU) 2017/2358 and (EU) 2017/2359 as regards the integration of sustainability factors, risks and preferences into the product oversight and governance requirements for insurance undertakings and insurance distributors and into the rules on conduct of business and investment advice for insurance-based investment products (1) . 18 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/1258 of 26 July 2021 entering a name in the register of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications (‘Őrségi tökmagolaj’ (PGI)) . -

Volume XIV, No. 1 31 January 2013

Volume XIV, No. 1 31 January 2013 ISSN 1555-774X. Copyright © 2013, PolishRoots®, Inc. Editor: William F. “Fred” Hoffman, e-mail: <[email protected]> CONTENTS Geneteka Letters to the Editor NEH-Funded Summer Seminar for teachers Update from the Poznań Project Upcoming Events More Useful Web Addresses You May Reprint Articles... *************************************** *** WELCOME! *** to the latest issue of Gen Dobry!, the e-zine of PolishRoots®. If you missed previous issues, you can find them here: <http://polishroots.org/GenDobry/tabid/60/Default.aspx> *************************************** Gen Dobry!, Vol. XIV, No. 1, January 2013 — 1 *** GENETEKA *** by Fred Hoffman <[email protected]> In case the title of this article seems a bit cryptic, I’m referring to a Website for Polish researchers at the following URL: <http://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/> We have mentioned Geneteka in Gen Dobry! before, but I’ve noticed several notes recently from people who have discovered it and want to sing its praises. It is worth attention, because it accesses databases of records indexed by Polish researchers. You start with a map of Poland with the provinces as they exist today, and you choose the one that includes your ancestral region. This takes you to a page that allows you to look for a specific surname (Nazwisko) in records of that province that have been indexed so far. In the box “Księga,” you specify what kind of records to search in; click “Wszystkie,” “all,” or select U (Urodzenia = births), M (Małżeństwa = marriages, or Z (Zgony = deaths). Specify a range of years in the boxes “od roku _” (from year _) and “do roku_” (to year _). -

Mapa Geośrodowiskowa Polski

P A Ń STWOWY INSTYTUT GEOLOGICZNY OPRACOWANIE ZAMÓWIONE PRZEZ MINISTRA ŚRODOWISKA OBJA ŚNIENIA DO MAPY GEO ŚRODOWISKOWEJ POLSKI 1:50 000 Arkusz ULANÓW (924) Warszawa 2007 1 Autorzy: BEATA BREITMEIER *, KRYSTYNA BUJAKOWSKA**, IZABELA BOJAKOWSKA***, ANNA BLI ŹNIUK***; PAWEŁ KWECKO***, HANNA TOMASSI –MORAWIEC*** Główny koordynator MG śP: MAŁGORZATA SIKORSKA-MAYKOWSKA*** Redaktor regionalny: BOGUSŁAW B ĄK*** Redaktor regionalny planszy B: DARIUSZ GRABOWSKI*** Redaktor tekstu: MARTA SOŁOMACHA*** *Przedsi ębiorstwo Geologiczne SA, al. Kijowska 14, 30-079 Kraków **Przedsi ębiorstwo Geologiczne SA POLGEOL, ul. Berezy ńska 39, 03-908 Warszawa ***Pa ństwowy Instytut Geologiczny, ul. Rakowiecka 4, 00-975 Warszawa ISBN..................... Copyright by PIG and M Ś, Warszawa 2007 2 Spis tre ści I. Wst ęp (B. Breitmeier) ....................................................................................................... 3 II. Charakterystyka geograficzna i gospodarcza (B. Breitmeier) ........................................... 4 III. Budowa geologiczna (B. Breitmeier) ................................................................................ 6 IV. Zło Ŝa kopalin (B. Breitmeier) ............................................................................................ 9 1. Surowce energetyczne – gaz ziemny ..................................................................... 12 2. Kopaliny okruchowe .............................................................................................. 12 3. Kopaliny ilaste....................................................................................................... -

Download.Xsp/WMP20100280319/O/M20100319.Pdf (Last Accessed 15 April 2018)

Milieux de mémoire in Late Modernity GESCHICHTE - ERINNERUNG – POLITIK STUDIES IN HISTORY, MEMORY AND POLITICS Herausgegeben von / Edited by Anna Wolff-Pow ska & Piotr Forecki ę Bd./Vol. 24 GESCHICHTE - ERINNERUNG – POLITIK Zuzanna Bogumił / Małgorzata Głowacka-Grajper STUDIES IN HISTORY, MEMORY AND POLITICS Herausgegeben von / Edited by Anna Wolff-Pow ska & Piotr Forecki ę Bd./Vol. 24 Milieux de mémoire in Late Modernity Local Communities, Religion and Historical Politics Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Cover image: © Dariusz Bogumił This project was supported by the National Science Centre in Poland grant no. DEC-2013/09/D/HS6/02630. English translation and editing by Philip Palmer Reviewed by Marta Kurkowska-Budzan, Jagiellonian University ISSN 2191-3528 ISBN 978-3-631-67300-3 (Print) E-ISBN 978-3-653-06509-1 (E-PDF) E-ISBN 978-3-631-70830-9 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-631-70831-6 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/b15596 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ © Zuzanna Bogumił / Małgorzata Głowacka-Grajper, 2019 Peter Lang –Berlin ∙ Bern ∙ Bruxelles ∙ New York ∙ Oxford ∙ Warszawa ∙ Wien This publication has been peer reviewed. www.peterlang.com Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Acknowledgments Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

Autor Nadsyłając Streszczenie Pracy Do Publikacji W Materiałach Zjazdowych Oświadcza Tym Samym, Że Nie Była I Nie Będzie

The Book of Articles National Scientific Conference “Knowledge – Key to Success” IV edition January 18, 2020, Toruń _______________________________________________________________________________ The Book of Articles National Scientific Conference “Knowledge – Key to Success” IV edition 1 The Book of Articles National Scientific Conference “Knowledge – Key to Success” IV edition January 18, 2020, Toruń _______________________________________________________________________________ Organizer: Promovendi Foundation Chairman of the Organizing Committee: Firaza Agnieszka Members of the Organizing Committee: Byczkowska Paulina Graczyk Andrzej Rosińska Karolina Solarczyk Paweł Wawrzyniak Dominika Editor: Kępczak Norbert Solarczyk Paweł Promovendi Foundation Publishing Adress: 17/19/28 Kamińskiego st. 90-229 Lodz, Poland KRS: 0000628361 NIP: 7252139787 REGON: 364954217 e-mail: [email protected] www.promovendi.pl ISBN: 978-83-955366-7-0 The papers included in this Book of Articles have been printed in accordance with the submitted texts after they have been accepted by the reviewers. The authors of individual papers are responsible for the lawful use of the materials used. Circulation: 60 copies Toruń, January 2020 2 The Book of Articles National Scientific Conference “Knowledge – Key to Success” IV edition January 18, 2020, Toruń _______________________________________________________________________________ Scientific Committee: Assoc. Prof. D.Sc. Ph.D. Andrzej Szosland – Lodz University of Technology Assoc. Prof. D.Sc. Ph.D. Marta Kadela – Building Research Institute in Warsaw Assoc. Prof. D.Sc. Ph.D. Jacek Sawicki – Lodz University of Technology D.Sc. Ph.D. Kamila Puppel – Warsaw University of Life Sciences D.Sc. Ph.D. Ryszard Wójcik – The Jacob of Paradies University in Gorzów Wielkopolski Ph.D. Norbert Kępczak – Lodz University of Technology Ph.D. Przemysław Kubiak – Lodz University of Technology Ph.D. -

Centrum Wikliniarstwa W Rudniku Nad Sanem Wickerwork Centre in Rudnik on San Program Pt

Centrum Wikliniarstwa w Rudniku nad Sanem Wickerwork Centre in Rudnik on San Program pt. „Centrum Wikliniarstwa w Rudniku nad Sanem” jest współnanso- wany przez Unię Europejską z Europejskiego Funduszu Rozwoju Regionalnego i budżet państwa w ramach Zintegrowanego Programu Operacyjnego Rozwoju Regionalnego. Centrum Wikliniarstwa w Rudniku nad Sanem Wickerwork Centre in Rudnik on San Rudnik 2007 Wydano na zlecenie Gminy i Miasta w Rudniku nad Sanem Commissioned by The Town and Commune of Rudnik Projekt i zdjęcia / Design and photographs by: Adam Krzykwa Zdjęcia Pawilonu EXPO: Urszula Bałutowska, Ingarden&Ewy Tekst polski opr. / Polish text by: Anna Garbacz Kartki z historii Rudnika na podst. książki: Zoa i Zdzisław Chmiel, Historia jednego miasta nad Sanem, Rudnik 1998. Cards of the history of Rudnik Town based on the book of Zoa and Zdzisław Chmiel, The history of the one Town on San, Rudnik 1998. Tekst angielski / English text by: Marek Wiatrowicz Korekta/Proof-reading: Danuta Nowak Skład / Typeset by: Marian Grzybowski © Wydawnictwo / Published by: IMAGE Adam Krzykwa Stalowa Wola tel. 015 844 12 91 ISBN 987-83-912854-4-8 CENTRUM WIKLINIARSTWA 37-420 Rudnik nad Sanem, ul. Mickiewicza 41 tel. (015) 876 16 46 [email protected] KARTKI Z HISTORII RUDNIKA CHAPTERS IN THE HISTORY OF RUDNIK CITY The city of three women Rudnik takes pride in its 400-year history. the squads of the famous Polish commander At the beginning of it history we can nd three Stefan Czarniecki, were coming from the neigh- Miasto trzech kobiet women. The rst one, Katarzyna Gnojeńska in bourhood of Przemyśl towards Sandomierz. One Rudnik szczyci się ponad 400-letnią historią. -

Regional Investment Attractiveness 2016

Warsaw School of Economics REGIONAL INVESTMENT ATTRACTIVENESS 2016 Subcarpathian Voivodship prof. Hanna Godlewska-Majkowska, Ph.D., Full Professor Agnieszka Komor, Ph.D. Dariusz Turek, Ph. D. Patrycjusz Zarębski, Ph.D. Mariusz Czernecki, M.A. Magdalena Typa, M.A. Report prepared for the Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency at the Institute of Enterprise, Warsaw School of Economics Warsaw, December 2016 20120166 Regional investment attractiveness 2016 Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency works to increase inflow of investments to Poland, development of Polish foreign investments and intensification of Polish export. Supporting entrepreneurs, the Agency assists in overcoming administrative and legal procedures related to specific projects. PAIiIZ helps, among others, in developing legal solutions, finding a suitable location, reliable partners and suppliers. PAIiIZ implements programs dedicated for expansion in promising markets: Go China, Go Africa, Go Arctic, Go India, Go ASEAN and Go Iran. In direct support of Polish companies on the site, the Agency successfully launches foreign branches. Detailed information about the services offered by PAIiIZ are available at: www.paiz.gov.pl 2 Regional investment attractiveness 2016 INTRODUCTION The report has been prepared to order of the Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency and is the next edition of the regional investment attractiveness reports. The reports have been published since 2008. They are the result of scientific research conducted since 2002 under the supervision of prof. H. Godlewska-Majkowska, Ph.D., full professor in the Warsaw School of Economics, in the Institute of Enterprise, Collegium of Business Administration of the Warsaw School of Economics. All the authors are the core members of a team that develops methodology of calculating regional investment attractiveness. -

10 (4) 2011 Issn 1644-0757

Acta Scientiarum Polonorum – ogólnopolskie czasopismo naukowe polskich uczelni rolniczych, publikuje oryginalne prace w następujących seriach tematycznych: ISSN 1644-0757 Agricultura – Agronomia Wydawnictwa Uczelniane Uniwersytetu Technologiczno-Przyrodniczego w Bydgoszczy ul. Ks. A. Kordeckiego 20, 85-225 Bydgoszcz, tel. 52 374 94 36, fax 52 374 94 27 Biologia – Biologia Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczo-Humanistycznego w Siedlcach ul. Bema 1, 08-110 Siedlce, tel. 25 643 15 20 Biotechnologia – Biotechnologia Geodesia et Descriptio Terrarum – Geodezja i Kartografi a Medicina Veterinaria – Weterynaria Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego we Wrocławiu ul. Sopocka 23, 50-344 Wrocław, tel./fax 71 328 12 77 Technica Agraria – Inżynieria Rolnicza Hortorum Cultus – Ogrodnictwo Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Lublinie ul. Akademicka 13, 20-033 Lublin, tel. 81 445 67 11, fax 81 533 37 52 Piscaria – Rybactwo Zootechnica – Zootechnika Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Zachodniopomorskiego Uniwersytetu Technologicznego w Szczecinie al. Piastów 50, 70-311 Szczecin, tel. 91 449 40 90, 91 449 41 39 Silvarum Colendarum Ratio et Industria Lignaria – Leśnictwo i Drzewnictwo Technologia Alimentaria – Technologia Żywności i Żywienia Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Poznaniu ul. Witosa 45, 61-693 Poznań, tel. 61 848 78 07, fax 61 848 78 08 Administratio Locorum – Gospodarka Przestrzenna Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warmińsko-Mazurskiego w Olsztynie ul. Heweliusza 14, 10-724 Olsztyn, tel. 89 523 36 61, fax 89 523 34 38 Architectura – Budownictwo Oeconomia -

Publications Office

15.4.2021 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union L 129/1 II (Non-legislative acts) REGULATIONS COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2021/605 of 7 April 2021 laying down special control measures for African swine fever (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Regulation (EU) 2016/429 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2016 on transmissible animal diseases and amending and repealing certain acts in the area of animal health (‘Animal Health Law’ (1)), and in particular Article 71(3) thereof Whereas: (1) African swine fever is an infectious viral disease affecting kept and wild porcine animals and can have a severe impact on the concerned animal population and the profitability of farming causing disturbance to movements of consignments of those animals and products thereof within the Union and exports to third countries. In the event of an outbreak of African swine fever, there is a risk that the disease agent may spread between establishments of kept porcine animals and in the metapopulations of wild porcine animals. The spread of the disease can significantly affect the productivity of the farming sector due to both direct and indirect losses. (2) Since 1978, the African swine fever virus has been present in Sardinia, Italy, and since 2014 there have been outbreaks of that disease in other Member States as well as in neighbouring third countries. Currently, African swine fever can be considered as endemic disease in the populations of porcine animals in a number of third countries bordering the Union and it represents a permanent threat for populations of porcine animals in the Union. -

Regional Investment Attractiveness 2014

Warsaw School of Economics REGIONAL INVESTMENT ATTRACTIVENESS 2014 Subcarpathian Voivodship Hanna Godlewska-Majkowska, Ph.D., Associate Professor at the Warsaw School of Economics Agnieszka Komor, Ph.D. 3DWU\FMXV]=DUĊEVNL3K' Mariusz Czernecki, M.A. Magdalena Typa, M.A. Report prepared for the Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency at the Institute of Enterprise, Warsaw School of Economics Warsaw, December 2014 2014 Regional investment attractiveness 2014 Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency (PAIiIZ) is a governmental institution and has been servicing investors since 1992. Its mission is to create a positive image of Poland in the world and increase the inflow of foreign direct investments by encouraging international companies to invest in Poland. PAIiIZ is a useful partner for foreign entrepreneurs entering the Polish market. The Agency guides investors through all the essential administrative and legal procedures that involve a project. It also provides rapid access to complex information relating to legal and business matters regarding investments. Moreover, it helps in finding the appropriate partners and suppliers together with new locations. PAIiIZ provides free of charge professional advisory services for investors, including: investment site selection in Poland, tailor-made investors visits to Poland, information on legal and economic environment, information on available investment incentives, facilitating contacts with central and local authorities, identification of suppliers and contractors, care of existing investors (support of reinvestments in Poland). Besides the OECD National Contact Point, PAIiIZ also maintains an Information Point for companies ZKLFK DUH LQWHUHVWHG LQ (XURSHDQ )XQGV $OO RI WKH $JHQF\¶V DFWLYLWLHV DUe supported by the Regional Investor Assistance Centres. Thanks to the training and ongoing support of the Agency, the Centres provide complex professional services for investors at voivodship level.