The Role of the Reader in the Fiction of Muḥammad Khuḍayyir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Iraq and Syria

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2017 The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria Zachary Kielp Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kielp, Zachary, "The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3225. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3225 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Zachary Kielp December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Zachary Kielp ii THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, December 2017 Master of Science Zachary Kielp ABSTRACT After the carnage of World War One and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire a new form of political organization was brought to the Middle East, the Nation-State. -

The American University in Cairo Press

TheThe AmericanAmerican 2009 UniversityUniversity inin Cairo Cairo PressPress Complete Catalog Fall The American University in Cairo Press, recognized “The American University in Cairo Press is the Arab as the leading English-language publisher in the region, world’s top foreign-language publishing house. It has currently offers a backlist of more than 1000 publica- transformed itself into one of the leading players in tions and publishes annually up to 100 wide-ranging the dialog between East and West, and has produced academic texts and general interest books on ancient a canon of Arabic literature in translation unmatched and modern Egypt and the Middle East, as well as in depth and quality by any publishing house in the Arabic literature in translation, most notably the works world.” of Egypt’s Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz. —Egypt Today New Publications 9 Marfleet/El Mahdi Egypt: Moment of Change 22 Abdel-Hakim/Manley Traveling through the 10 Masud et al. Islam and Modernity Deserts of Egypt 14 McNamara The Hashemites 28 Abu Golayyel A Dog with No Tail 23 Mehdawy/Hussein The Pharaoh’s Kitchen 31 Alaidy Being Abbas el Abd 15 Moginet Writing Arabic 2 Arnold The Monuments of Egypt 30 Mustafa Contemporary Iraqi Fiction 31 Aslan The Heron 8 Naguib Women, Water, and Memory 29 Bader Papa Sartre 20 O’Kane The Illustrated Guide to the Museum 9 Bayat Life as Politics of Islamic Art 13 al-Berry Life is More Beautiful than Paradise 2 Ratnagar The Timeline History of Ancient Egypt 15 Bloom/Blair Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art 33 Roberts, R.A. -

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven Mediävistischer Forschung

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 5 Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Textile Inscriptions on Royal Garments from Norman Sicily Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) ISBN 978-3-11-053202-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-053387-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-053212-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Satzstudio Borngräber, Dessau-Roßlau Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Preface — IX Introduction — XI Chapter I Shaping Perceptions: Reading and Interpreting the Norman Arabic Textile Inscriptions — 1 1 Arabic-Inscribed Textiles from Norman and Hohenstaufen Sicily — 2 2 Inscribed Textiles and Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts — 43 3 Historical Receptions of the Ceremonial Garments from Norman Sicily — 51 4 Approaches to Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts: Methodological Considerations — 64 Chapter II An Imported Ornament? Comparing the Functions -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

The Frailty of Authority. Borders, Non-State Actors and Power

The Frailty of Authority Borders, Non-State Actors and Power Vacuums in a Changing Middle East Lorenzo Kamel THE FRAILTY OF AUTHORITY BORDERS, NON-STATE ACTORS AND POWER VACUUMS IN A CHANGING MIDDLE EAST edited by Lorenzo Kamel in collaboration with Edizioni Nuova Cultura First published 2017 by Edizioni Nuova Cultura For Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) Via Angelo Brunetti 9 - I-00186 Rome www.iai.it Copyright © 2017 Edizioni Nuova Cultura - Rome ISBN: 9788868128289 Cover: by Luca Mozzicarelli Graphic Composition: by Luca Mozzicarelli The unauthorized reproduction of this book, even partial, carried out by any means, including photocopying, even for internal or didactic use, is prohibited by copyright. Table of contents List of contributors ........................................................................................................................................ 7 List of abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Preface, by Nicolò Russo Perez ............................................................................................................... 11 Introduction, by Lorenzo Kamel ............................................................................................................ 15 1. Early Warning Signs in the Arab World That We Ignored – And Still Ignore by Rami G. Khouri .................................................................................................................................. -

Fantasy Cartography

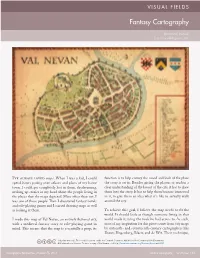

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

The Qur'an's Challenge: a Literary & Linguistic Miracle (Original Article At

The Qur'an's Challenge: A Literary & Linguistic Miracle (Original article at: http://www.hamzatzortzis.com/essays-articles/exploring-the-quran/the-inimitable-quran/) “Read! In the Name of your Lord Who has created. He has created man from a leech-like clot. Read! And your Lord is the Most Generous. Who has taught (the writing) by the pen. He has taught man that which he knew not.” Surah Al-’Alaq (The Clot) 96: 1-5 These were the first verses of the Qur’an to be revealed to Prophet Muhammad (upon whom be peace) over fourteen hundred years ago. Prophet Muhammad, who was known to have been in retreat and meditation in a cave outside Makkah, had received the first revelation of a book that would have a tremendous impact on the world. Not being able to read or write or known to have composed any piece of poetry and not having any special rhetorical gifts, Prophet Muhammad had just received the beginning of a book that would deal with matters of belief, law, politics, rituals, spirituality, and economics in an entirely new literary form. This unique literary form is part of the miraculous nature of the Qur’an, that led to the dramatic intellectual revival of desert Arabs. Thirteen years after the first revelation, it became the primary reference for a new state in Madinah, providing the new civilisation’s political, philosophical, and spiritual outlook. In this chapter, we will begin to examine why the Qur’an is impossible to imitate by reviewing how the language of the Qur’an compares to the normal literary forms of Arabic poetry and prose. -

The Unique Necklace Volume.Pdf

Great Books of Islamic Civilization Ibn ∏Abd The Center for Muslim Contribution to Civilization Rabbih the Unique Necklace the l-‘Iqd al-Farı¯d (The Unique Necklace) is one of the classics of Arabic literature. the Compiled in several volumes by an Andalusian scholar and poet named Ibn Unique Necklace A‘Abd Rabbih (246–328 A.H. / 860–940 C.E.),it remains a mine of information about various elements of Arab culture and letters during the four centuries before his death.Essentially it is a book of adab,a term understood in modern times to specifically II Volume mean literature but in earlier times its meaning included all that a well-informed person had to know in order to pass in society as a cultured and refined individual.This Unique meaning later evolved and included belles lettres in the form of elegant prose and verse that was as much entertaining as it was morally educational, such as poetry, pleasant anecdotes, proverbs, historical accounts, general knowledge, wise maxims, and even practical philosophy. Ibn ‘Abd Rabbih’s imagination and organization saved his encyclopedic Necklace compendium from becoming a chaotic jumble of materials by conceiving of it as a necklace composed of twenty-five ‘books’, each of which carried the name of a jewel. Each of the twenty-five ‘books’ was organized around a major theme and had an introduction written by Ibn ‘Abd Rabbih, followed by his relevant adab selections of Volume II verse and prose on the theme of the ‘book’. He drew on a vast repertoire of sources including the Bible,the Qur’an and the Hadith,and the works of al-Jahiz,ibn Qutayba, al-Mubarrad,Abu ‘Ubayda ibn al-Muthanna and several others, as well as the diwans of many Arab poets, including his own poetry. -

Sung Poetry in the Oral Tradition of the Gulf Region and the Arabian Peninsula

Oral Tradition, 4/1-2 (1989): 174-88 Sung Poetry in the Oral Tradition of the Gulf Region and the Arabian Peninsula Simon Jargy Historical Background As far back as we can go in the past history of the Arabs and Arabia, we fi nd poetry present as a huge memorial to their real and imaginary heroic exploits, as a witness to their way of life and feelings, and most of all as an expression of the deepest roots of their soul. Being essentially oral in its origins and developments, this poetry, with its rhythms, intonations, accents, and long or short syllables fi tted in quite naturally with music. In the old classical Arabic terminology, poetry (Shicr) identifi es with song (Nashīd): reciting it is synonymous with singing it (Anshada al-Shicr). This bond between Shicr (poetry) and Inshād (chant or recitative) still has the same meaning in the spoken Arabic of the Peninsula and the Gulf region where Nishīda (song) is synonymous with Giṣīda (poem). In pre-Islamic Arabia, Inshād likely had a dual function: religious and social. Both stem from the rhythmical syllables of the Arabic language (rhymed prose: Sajc, and metrical poetry: Shicr), as well as from rhythmical movements of camels. Coming from ancient times, this is the Ḥidā’ (literally “stimulating the camel’s step”) that the Bedouin sings following the steps of his camel and for his own entertainment. It has survived in the actual form we call “recitative” or “cantilena,” as the common Ḥadwā still designates, in the spoken Bedouin dialect of the Gulf, the folk songs of both the desert and the sea. -

Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Bevilacqua, Alexander and Loop, Jan (2018) The Qur’an in Comparison and the Birth of ‘scriptures’. Journal of Qur'anic Studies . ISSN 1465-3591. (In press) DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/68852/ Document Version Author's Accepted Manuscript Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html The Qur’an in Comparison and the Birth of ‘scriptures’* Alexander Bevilacqua (WILLIAMS COLLEGE) Jan Loop (UNIVERSITY OF KENT) The Qur’an was a protean book in early modern Europe. From the sixteenth century to the eighteenth, Europeans developed several distinct ways of thinking about it and about the person whom they took to be its author, the Prophet Muammad. Medieval Western Christians already regarded the Qur’an as a lawbook. -

Abstract Title of Dissertation: NEGOTIATING the PLACE OF

Abstract Title of Dissertation: NEGOTIATING THE PLACE OF ASSYRIANS IN MODERN IRAQ, 1960–1988 Alda Benjamen, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation Directed by: Professor Peter Wien Department of History This dissertation deals with the social, intellectual, cultural, and political history of the Assyrians under changing regimes from the 1960s to the 1980s. It examines the place of Assyrians in relation to a state that was increasing in strength and influence, and locates their interactions within socio-political movements that were generally associated with the Iraqi opposition. It analyzes the ways in which Assyrians contextualized themselves in their society and negotiated for social, cultural, and political rights both from the state and from the movements with which they were affiliated. Assyrians began migrating to urban Iraqi centers in the second half of the twentieth century, and in the process became more integrated into their societies. But their native towns and villages in northern Iraq continued to occupy an important place in their communal identity, while interactions between rural and urban Assyrians were ongoing. Although substantially integrated in Iraqi society, Assyrians continued to retain aspects of the transnational character of their community. Transnational interactions between Iraqi Assyrians and Assyrians in neighboring countries and the diaspora are therefore another important phenomenon examined in this dissertation. Finally, the role of Assyrian women in these movements, and their portrayal by intellectuals, -

Comparative Literature (09/21/21)

Bulletin 2021-22 Comparative Literature (09/21/21) and colorful text read first in its entirety and then more carefully Comparative in pieces. Supplementary readings are from the abundant other sources on and interpretations of Nero, both ancient and modern. Discussions and writing assignments are varied and Literature designed to develop analytical and writing skills. Same as L08 Classics 137 Credit 3 units. A&S: FYS A&S IQ: HUM, LCD Art: HUM BU: Contact: Eldina Kandzetovic HUM EN: H Phone: 314-935-5170 Email: [email protected] L16 Comp Lit 153 Laughter: From Aristotle to Seinfeld Website: http://complit.wustl.edu Reading courses, each limited to 15 students. Topics: selected writers, varieties of approaches to literature, e.g., Southern Courses fiction, the modern American short story, the mystery; consult course listings. Prerequisite: first-year standing. Visit online course listings to view semester offerings for Same as L14 E Lit 153 L16 Comp Lit (https://courses.wustl.edu/CourseInfo.aspx? Credit 3 units. A&S: FYS A&S IQ: HUM sch=L&dept=L16&crslvl=1:4). L16 Comp Lit 176C First-Year Seminar: Aesop and His Fables: Comedy and Social Criticism L16 Comp Lit 1024 Mozart: The Humor, Science, and Politics In ancient Athens, each citizen had the power to prosecute of Music others for wrongs committed not only against him but also Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is one of the most recognized against society as a whole. Each citizen defended himself composers of "classical" music. A child prodigy of astonishing without aid of lawyers and judges. This system depended upon precocity, he has come to symbolize genius for Western culture an intensely democratic structure of jury courts and laws and — a composer whose music embodies superhuman, even upon the development of rhetoric as an artful speech by which Utopian beauty and perfection.