Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven Mediävistischer Forschung

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 5 Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Textile Inscriptions on Royal Garments from Norman Sicily Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) ISBN 978-3-11-053202-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-053387-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-053212-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Satzstudio Borngräber, Dessau-Roßlau Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Preface — IX Introduction — XI Chapter I Shaping Perceptions: Reading and Interpreting the Norman Arabic Textile Inscriptions — 1 1 Arabic-Inscribed Textiles from Norman and Hohenstaufen Sicily — 2 2 Inscribed Textiles and Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts — 43 3 Historical Receptions of the Ceremonial Garments from Norman Sicily — 51 4 Approaches to Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts: Methodological Considerations — 64 Chapter II An Imported Ornament? Comparing the Functions -

The Qur'an's Challenge: a Literary & Linguistic Miracle (Original Article At

The Qur'an's Challenge: A Literary & Linguistic Miracle (Original article at: http://www.hamzatzortzis.com/essays-articles/exploring-the-quran/the-inimitable-quran/) “Read! In the Name of your Lord Who has created. He has created man from a leech-like clot. Read! And your Lord is the Most Generous. Who has taught (the writing) by the pen. He has taught man that which he knew not.” Surah Al-’Alaq (The Clot) 96: 1-5 These were the first verses of the Qur’an to be revealed to Prophet Muhammad (upon whom be peace) over fourteen hundred years ago. Prophet Muhammad, who was known to have been in retreat and meditation in a cave outside Makkah, had received the first revelation of a book that would have a tremendous impact on the world. Not being able to read or write or known to have composed any piece of poetry and not having any special rhetorical gifts, Prophet Muhammad had just received the beginning of a book that would deal with matters of belief, law, politics, rituals, spirituality, and economics in an entirely new literary form. This unique literary form is part of the miraculous nature of the Qur’an, that led to the dramatic intellectual revival of desert Arabs. Thirteen years after the first revelation, it became the primary reference for a new state in Madinah, providing the new civilisation’s political, philosophical, and spiritual outlook. In this chapter, we will begin to examine why the Qur’an is impossible to imitate by reviewing how the language of the Qur’an compares to the normal literary forms of Arabic poetry and prose. -

The Unique Necklace Volume.Pdf

Great Books of Islamic Civilization Ibn ∏Abd The Center for Muslim Contribution to Civilization Rabbih the Unique Necklace the l-‘Iqd al-Farı¯d (The Unique Necklace) is one of the classics of Arabic literature. the Compiled in several volumes by an Andalusian scholar and poet named Ibn Unique Necklace A‘Abd Rabbih (246–328 A.H. / 860–940 C.E.),it remains a mine of information about various elements of Arab culture and letters during the four centuries before his death.Essentially it is a book of adab,a term understood in modern times to specifically II Volume mean literature but in earlier times its meaning included all that a well-informed person had to know in order to pass in society as a cultured and refined individual.This Unique meaning later evolved and included belles lettres in the form of elegant prose and verse that was as much entertaining as it was morally educational, such as poetry, pleasant anecdotes, proverbs, historical accounts, general knowledge, wise maxims, and even practical philosophy. Ibn ‘Abd Rabbih’s imagination and organization saved his encyclopedic Necklace compendium from becoming a chaotic jumble of materials by conceiving of it as a necklace composed of twenty-five ‘books’, each of which carried the name of a jewel. Each of the twenty-five ‘books’ was organized around a major theme and had an introduction written by Ibn ‘Abd Rabbih, followed by his relevant adab selections of Volume II verse and prose on the theme of the ‘book’. He drew on a vast repertoire of sources including the Bible,the Qur’an and the Hadith,and the works of al-Jahiz,ibn Qutayba, al-Mubarrad,Abu ‘Ubayda ibn al-Muthanna and several others, as well as the diwans of many Arab poets, including his own poetry. -

Sung Poetry in the Oral Tradition of the Gulf Region and the Arabian Peninsula

Oral Tradition, 4/1-2 (1989): 174-88 Sung Poetry in the Oral Tradition of the Gulf Region and the Arabian Peninsula Simon Jargy Historical Background As far back as we can go in the past history of the Arabs and Arabia, we fi nd poetry present as a huge memorial to their real and imaginary heroic exploits, as a witness to their way of life and feelings, and most of all as an expression of the deepest roots of their soul. Being essentially oral in its origins and developments, this poetry, with its rhythms, intonations, accents, and long or short syllables fi tted in quite naturally with music. In the old classical Arabic terminology, poetry (Shicr) identifi es with song (Nashīd): reciting it is synonymous with singing it (Anshada al-Shicr). This bond between Shicr (poetry) and Inshād (chant or recitative) still has the same meaning in the spoken Arabic of the Peninsula and the Gulf region where Nishīda (song) is synonymous with Giṣīda (poem). In pre-Islamic Arabia, Inshād likely had a dual function: religious and social. Both stem from the rhythmical syllables of the Arabic language (rhymed prose: Sajc, and metrical poetry: Shicr), as well as from rhythmical movements of camels. Coming from ancient times, this is the Ḥidā’ (literally “stimulating the camel’s step”) that the Bedouin sings following the steps of his camel and for his own entertainment. It has survived in the actual form we call “recitative” or “cantilena,” as the common Ḥadwā still designates, in the spoken Bedouin dialect of the Gulf, the folk songs of both the desert and the sea. -

Inquiries Into Proto-World Literatures: the Challenging “Literary Fate” Of

FOCUS 38 Modern studies in Persian prosody fre- quently debate the origin of the quatrain Inquiries into Proto-World (Per. robā‛ī - Ar. rubā‛ī)1 as a metrical form Literatures: The Challenging which clearly arose in an indigenous lyrical tradition. This identifies quatrains as the “Literary Fate” of the Quatrain entry point to claim Persian prosodic pat- terns as having an independent origin across the Persian and from the Arabic ones. However, late 20th century scholarship relies on a response- Arabic Literary Tradition approach to the matter, and is essentially grounded in dismantling Arabo-centric prosodic categorization - i.e. founded on the Khalīlian prosodic model2 - which gathers both traditions since the 9th cen- tury, rather than on overcoming the Khalīlian framework as a self-evident late feature within the earlier Persian lyrical tra- dition. Chiara Fontana Recent studies of comparative prosody among Arabic-Persian-Urdu and Turkish Western studies on Persian metrical sys- poetry. This study closely investigates the works (e.g. Ashwini and Kiparsky 147-173) tem debate the linguistic origins of qua- spread of robāʽī/rubāʽī from Persian to broaden Prince and Paoli’s approach to trains, (Per. robāʽiyyāt - Ar. rubāʽiyyāt) in Arabic literature employing a holistic cul- generative prosody across Middle Eastern Arabic, and regard prosodic Persian turally embedded methodology to re- languages, yet the analysis of the quatrain schemes independently of Arabic coun- read their linkages in global terms, as an is still essentially founded on metrical terparts, despite reciprocally influenced example of an inherited “Proto-World observations. This partial perspective may metrical patterns. Attempts to dismantle Literature”. -

The Aesthetics of Saj'in the Quran and Its Influence on Music

Fatemeh Karimi Tarki Int. Journal of Engineering Research and Applications www.ijera.com ISSN : 2248-9622, Vol. 3, Issue 5, Sep-Oct 2013, pp.830-833 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS The Aesthetics Of Saj‘In The Quran And Its Influence On Music By The Survey Of Saj‘And The Music In Surah Al-Takwir Fatemeh Karimi Tarki Theological and Arabic Language Department, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran Abstract The Quran is a miracle and it is proved in different aspects. If you consider the philosophy of it appearance in Jahiliyyah times –the Arabs were really grate in composing poems - you will understand the most important aspect of its miracle is the eloquence. A lot of expert fishermen have tried to achieve eloquence pearls in the Quran ocean and search for eloquence aspects in the book. They have found Maani, Bayan and Badii` pearls in this ocean full of different pearls. This essay tries to image a little of this ocean beauties for the readers. Aesthetics of Saj‘ in the Quran and its influence on the special music of its verses is the subject of this essay by considering the saj‘ and music in surah al-Takwir. Key words: saj‘, the Quran, music, surah al-Takwir I. Introduction you feel great by reading or hearing an artificial and Before starting the discussion, it is better to wise speech. introduce some terms like saj‘, music and Aesthetics. III. Music Saj‘ Abū Naṣr Al-Farabi in his book kitāb iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm The meaning of this word is pigeon's song. As (On the Introduction of Knowledge) says that music is a a term it means using some words that are similar in the knowledge of songs, and it includes two parts: one of last letter(s) or rhythm in prose. -

Stories and Travel Diaries Relating to the Universal Expositions in Paris (1867, 1889, 1900)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenstarTs Cristiana Baldazzi The Arabs in the Mirror: Stories and Travel Diaries relating to the Universal Expositions in Paris (1867, 1889, 1900) Our object is to visit this Fair or ‘Ukāẓ’ of provinces and nations, this market of fortunes and ambitions, spectacle of precious objects and prestigious projects, of strengths and energies, arena of inventions and innovations, exhibition of perspicacity and guide in the art of imitation and inspiration of the tradition.1 It is thus that the Egyptian writer Muḥammad al-Muwayliḥī (1858-1930)2 defines the Paris Exposition of 1900 which he chose as the place wherein to set the second part3 of his work Ḥadīṯ ‘Īsà ibn Hišām,4 one of the first modern Arab novels which follows in 1 M. Muwayliḥī, Ḥadīṯ ‘Īsa ibn Hišām. Fatra min al-zaman (Cairo: Kalimāt ‘arabiyya lil-tarǧama wa al-našr, 2013), 275. 2 His date of birth is uncertain, 1858 o 1868, especially considering that of his father, Ibrāhīm, which is also uncertain 1844. The author, in the company of his father, traveled in Italy, England and France, where he came in contact with many writers and intellectuals. In 1900 he accompanied the Egyptian Khe- divé on an official visit first to London then to Paris for the Universal Exposition. Cf. R. Allen, A Period of Time. Part One: A Study of Muḥammad al-Muwayliḥī’ s Ḥadīṯ ‘Īsā ibn Hišām (London: Ithaca Press, 1992), 1-14; A. Sābāyārd, Raḥḥālūna al-‘Arab wa ḥaḍārat al-ġarb fī al-nahḍa al-‘arabiyya al-ḥadīṯa (Beirut: Nawfal, 19922), 146-147. -

Essay: the Fu: China and the Origins of the Prose Poem Morton Marcus

THE PROSE POEM: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL Volume 8 | 1999 Essay: The Fu: China And The Origins Of The Prose Poem Morton Marcus © Providence College The author(s) permits users to copy, distribute, display, and perform this work under the following conditions: (1) the original author(s) must be given proper attribution; (2) this work may not be used for commercial purposes; (3) the users may not alter, transform, or build upon this work; (4) users must make the license terms of this work clearly known for any reuse or distribution of this work. Upon request, as holder of this work’s copyright, the author(s) may waive any or all of these conditions. The Prose Poem: An International Journal is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress) for the Providence College Digital Commons. http://digitalcommons.providence.edu/prosepoems/ ESSAY THE FU: CHINA AND THE ORIGINS OF THE PROSE POEM There is a popular notion among prose poets and literati from Europe and the Americas that the prose poem originated in the early nineteenth century with Aloysius Bertrand's Gaspard de la Nuit, and that Baudelaire continued its development in Le Spleen de Paris (Paris Spleen). Then Rimbaud followed with Les Illuminations, and a half-dozen other poets, almost all French, brought the form into the twentieth century. In reality, the prose poem started in China during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), where it was known as fu, or rhymed prose. Essentially the fu was a court entertainment written for the emperor or for other nobles' amusement to accompany ceremonies, rituals and informal gatherings. -

Love and Race in a Thirteenth-Century Romance in Hebrew, with a Translation of the Story of Maskil and Peninah by Jacob Ben El)Azar*

10fl_23.1_rosen.qxd 2008/11/19 16:02 PM Page 155 Love and Race in a Thirteenth-Century Romance in Hebrew, with a Translation of The Story of Maskil and Peninah by Jacob Ben El)azar* Tova Rosen The Story of Maskil and Peninah is a romance, cast in the Arabic genre of the maqama¯h, and written in biblical Hebrew by a Jewish author in thirteenth-century Christian Toledo. This cultural juncture, anchored in the work’s historical circumstances is, as I intend to show, also reflected in the complexities of the story’s plot: an army (apparently Chris- tian) invades a Muslim territory; its commander falls in love with an Arabic princess taken captive; the couple encounter a black giant warrior and, after killing him, live happily ever after. Very little is known about the author, Jacob Ben El)azar (in Castilian, Abenalazar), who lived in the late twelfth to early thirteenth century. He was also the author of com- positions on popular philosophy (in Hebrew) and of a Hebrew grammar (in Arabic), as well as the translator (from Arabic to Hebrew) of the famous Arabic narrative collec- tion of Kalila¯h and Dimna¯h.1 The Story of Maskil and Peninah (translated below) is the sixth of ten rhymed pieces in Ben El)azar’s narrative collection known as Sefer ha-meshalim (Book of Fables), dated * Dedicated to Sheila Delany, whose interest in medieval Hebrew literature encouraged me to translate this text. 1 On Ben El)azar’s work, see Schirmann and Fleischer, The History of Hebrew Poetry, 222-55, and the bibliography therein. -

Walking the Tightrope of Invisibility in Palestinian Translated Fiction Mona Nabeel Malkawi University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 1-2016 Twice Heard, Paradoxically (Un)seen: Walking the Tightrope of Invisibility in Palestinian Translated Fiction Mona Nabeel Malkawi University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Malkawi, Mona Nabeel, "Twice Heard, Paradoxically (Un)seen: Walking the Tightrope of Invisibility in Palestinian Translated Fiction" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1769. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1769 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Twice Heard, Paradoxically (Un)seen: Walking the Tightrope of Invisibility in Palestinian Translated Fiction A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Mona Nabeel Malkawi Yarmouk University Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Literature, 2006 Yarmouk University Master of Arts in Translation, 2009 December 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council: ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Professor John DuVal Dissertation Director ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Professor Adnan Haydar Professor Charles Adams Committee Member Committee Member ©2016 by Mona Nabeel Malkawi All Rights Reserved Abstract This study examines the translators’ invisibility in postcolonial translated Palestinian fiction. On one hand, this analysis revolves around the ethical stance of translators towards authors in a postcolonial theoretical framework. -

Arabic Poetry As Teaching Material in Early Modern Grammars and Textbooks*

230 Loop Chapter 9 Arabic Poetry as Teaching Material in Early Modern Grammars and Textbooks* Jan Loop Excerpts of Christian texts and of the Qur’an were not the only texts with which the early modern students of Arabic could exercise the grammatical rules of the language. From the very beginning, Arabic poetry played an impor- tant role as a literary genre that was esteemed to be of central cultural importance to the Arabs and thus deserved a special place in the teaching and learning of their language. Hence, it was in textbooks and grammars that European scholars first printed specimens of Arabic poetry, together with accounts of the system of Arabic prosody. Usually these editions were equipped with detailed grammatical, syntactical, semantic and metrical comments, while questions of historical circumstances, of cultural functions and poetical traditions were only occasionally discussed. Based on an analysis of published textbooks and grammars, the following essay gives a survey of the first European encounters with Arabic poetry and it assesses its significance for the teaching and learning of Arabic. … As with Arabic literature and culture in general, the seventeenth century also witnessed a new interest in Arabic poetry. We find a testimony to this new appreciation of the Arabic poetical heritage in Thomas Erpenius’s famous Oration on the Value of the Arabic Language, held in Leiden in 1620: There are not in the rest of the world nor were there ever, as many poets as in Arabia alone. I am not lying, dear listeners. They number sixty poets * I have presented a first draft of this paper in March 2011 at Christopher Ligota’s seminar The History of Scholarship and I read revised versions at the conference Poetics and Knowledge in Early Modern Europe, Merton College, Oxford, 23 May 2013 and at the workshop Arab Culture and the European Renaissance, New York University, Abu Dhabi, 14–15 April 2013. -

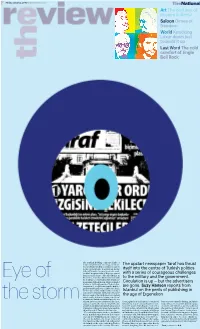

Artthe Civil War of Images in Beirut Saloondimes of Freedom

r Friday, January 2, 2009 www.thenational.ae The N!tion!l Art The civil war of images in Beirut Saloon Dimes of freedom World Knocking Luxor down just to build it up Last Word The cold comfort of Jingle Bell Rock The Turkish holding company Alarko, a major conglomerate of energy, construc- The upstart newspaper Taraf has thrust tion and tourism firms, resides in a pink former psychiatric hospital up in the itself into the centre of Turkish politics hills off Istanbul’s stunning shore road, on the European side of the city, across with a series of courageous challenges from a seaside dance club called Reina. In December, I went to Alarko to meet with to the military and the government. its chairman, a Turkish-Jewish business- Eye of man named Ishak Alaton. Alaton founded Circulation is up – but the advertisers Alarko in 1954 with another Turkish Jew, Uzeyir Garih, and the two ran the firm to- are gone. Suzy Hansen reports from gether until Garih was stabbed to death in 2001 by a young soldier while visiting a Istanbul on the perils of publishing in cemetery in Istanbul. At the time the mur- der was seen as the random act of a violent the age of Ergenekon psychopath, absent religious or political motivation. But the week that I went to see the storm Alaton, prosecutors reopened the case, sive Ergenekon indictment contained lent sense of comedic timing, and punc- suggesting that the murder was linked to allegations that the group had been con- tuated his sentences with dramatic paus- a mysterious ultranationalist gang called nected to a secret intelligence unit of the es and heavy syllables, as if he admired Ergenekon, whose intrigues have captivat- military police called JITEM, which some the oeuvre of Chris Rock.