A Phenomenological Inquiry Into Sacred Time in Hinduism Netty Provost Purdue University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heidegger and Indian Thinking: the Hermeneutic of a “Belonging-Together” of Negation and Affirmation

Comparative Philosophy Volume 6, No. 1 (2015): 111-128 Open Access / ISSN 2151-6014 www.comparativephilosophy.org HEIDEGGER AND INDIAN THINKING: THE HERMENEUTIC OF A “BELONGING-TOGETHER” OF NEGATION AND AFFIRMATION JAISON D. VALLOORAN ABSTRACT: According to Heidegger the questioning of Being is unique to western philosophical tradition, however we see that the hermeneutic of Being is explicit in inter- cultural context of thinking. Understanding Brahman as “one” and “the same” Śankara speaks together with Heidegger the same hermeneutic of ontological monism. Due to the reason that there is no explicit terminological equivalent of the word ‘Being’ in Śankara’s thinking, the hermeneutic of Śankara’s ontological understanding of Brahman and its distinction as “Saguna” and “Nirguna” are not sufficiently explored. In an inter-cultural ontological context, it is important not to insist on terminological equivalence, but to search for hermeneutic depth. Similarly Madhyamaka-Buddhism of Nāgārjuna describes the universe as totally devoid of reality, called ‘Śūnya’ or void, which is an expression of nihilism; it is comparable to Heidegger’s observation of the concealing of Being as “nihil”. The hermeneutic of these explicit ontological characters of Being, as concealment and un- concealment allow us to discover a sabotaging brotherhood, because the nihil and something are ontologically two essential sides of the same thinking. Keywords: Heidegger, Śankara, Nāgārjuna, Inter-cultural Ontology, Indian Philosophy 1. INTRODUCTION Philosophies give explanations of the world, of “what” of beings, and set norms for the right relationships between human beings. Therefore it is an exclusive property of mankind; still it is an intellectual engagement in an individual culture in its highest level. -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

S. No. Name of the Ayurveda Medical Colleges

S. NO. NAME OF THE AYURVEDA MEDICAL COLLEGES Dr. BRKR Govt Ayurvedic CollegeOpp. E.S.I Hospital, Erragadda 1. Hyderabad-500038 Andhra Pradesh Dr.NR Shastry Govt. Ayurvedic College, M.G.Road,Vijayawada-520002 2. Urban Mandal, Krishna District Andhra Pradesh Sri Venkateswara Ayurvedic College, 3. SVIMS Campus, Tirupati North-517507Andhra Pradesh Anantha Laxmi Govt. Ayurvedic College, Post Laxmipura, Labour Colony, 4. Tq. & Dist. Warangal-506013 Andhra Pradesh Government Ayurvedic College, Jalukbari, Distt-Kamrup (Metro), 5. Guwahati- 781014 Assam Government Ayurvedic College & Hospital 6. Kadam Kuan, Patna 800003 Bihar Swami Raghavendracharya Tridandi Ayurved Mahavidyalaya and 7. Chikitsalaya,Karjara Station, PO Manjhouli Via Wazirganj, Gaya-823001Bihar Shri Motisingh Jageshwari Ayurved College & Hospital 8. Bada Telpa, Chapra- 841301, Saran Bihar Nitishwar Ayurved Medical College & HospitalBawan Bigha, Kanhauli, 9. P.O. RamanaMuzzafarpur- 842002 Bihar Ayurved MahavidyalayaGhughari Tand, 10. Gaya- 823001 Bihar Dayanand Ayurvedic Medical College & HospitalSiwan- 841266 11. Bihar Shri Narayan Prasad Awathy Government Ayurved College G.E. Road, 12. Raipur- 492001 Chhatisgarh Rajiv Lochan Ayurved Medical CollegeVillage & Post- 13. ChandkhuriGunderdehi Road, Distt. Durg- 491221 Chhatisgarh Chhatisgarh Ayurved Medical CollegeG.E. Road, Village Manki, 14. Dist.-Rajnandgaon 491441 Chhatisgarh Shri Dhanwantry Ayurvedic College & Dabur Dhanwantry Hospital 15. Plot No.-M-688, Sector 46-B Chandigarh- 160017 Ayurved & Unani Tibbia College and HospitalAjmal Khan Road, Karol 16. Bagh New Delhi-110005 Chaudhary Brahm Prakesh Charak Ayurved Sansthan 17. Khera Dabur, Najafgarh, New Delhi-110073 Bharteeya Sanskrit Prabodhini, Gomantak Ayurveda Mahavidyalaya & Research Centre, Kamakshi Arogyadham Vajem, 18. Shiroda Tq. Ponda, Dist. North Goa-403103 Goa Govt. Akhandanand Ayurved College & Hospital 19. Lal Darvaja, Bhadra Ahmedabad- 380001 Gujarat J.S. -

When Did Kali Yuga Start, How Long Is/Was It, and When Will It (Or Did It) End?

When did Kali Yuga start, how long is/was it, and when will it (or did it) end? In the book The Holy Science (1894) Sri Yukteswar clarified that a complete Yuga Cycle takes 24,000 years, and is comprised of an ascending cycle of 12,000 years when virtue gradually increases and a descending cycle of another 12,000 years, in which virtue gradually decreases (See the above figure). Hence, after we complete a 12,000-year descending cycle from Satya Yuga -> Kali Yuga, the sequence reverses itself, and an ascending cycle of 12,000 years begins which goes from Kali Yuga -> Satya Yuga. Yukteswar states that, “Each of these periods of 12,000 years brings a complete change, both externally in the material world, and internally in the intellectual or electric world, and is called one of the Daiva Yugas or Electric Couple.” Unfortunately, the start and end dates as well as the duration of the ages are not agreed upon, and Sri Yukteswar (who I have deep faith in) is one of many individuals that have laid out differing dates, times, and structures. “In spite of the elaborate theological framework of the Yuga Cycle, the start and end dates of the Kali Yuga remain shrouded in mystery. The popularly accepted date for the beginning of the Kali Yuga is 3102 BCE, thirty-five years after the conclusion of the battle of the Mahabharata.” This quote is taken from a well-researched article, “The End of the Kali Yuga in 2025: Unravelling the Mysteries of the Yuga Cycle in the New Dawn online magazine which can be found HERE. -

INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK, TIRUMALA BRANCH PHONE: 0877-2277718/2277887 II FLOOR, BALAJI BANKING COMPLEX EMAIL: [email protected] TIRUMALA

INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK, TIRUMALA BRANCH PHONE: 0877-2277718/2277887 II FLOOR, BALAJI BANKING COMPLEX EMAIL: [email protected] TIRUMALA Dear Sir/Madam, We have pleasure to inform you the Trusts maintained by TTD and donations accepted by them through our Bank. You can donate to TTD trusts from any of our Branches free of charge or from any bank through NEFT/RTGS. TTD DONATION SCHEMES 1. SRI VENKATESWARA NITYA ANNA PRASADAM TRUST With an aim to serve free food in the name of “Anna Prasadam” to the visiting pilgrims TTD has started Sri Venkateswara Nitya Annaprasadam Trust. Contribute generously towards this trust. The Donor can also offer largesse in the form of vegetables to this trust. Income Tax Exemption under Sec 80G allowed. 2. SRI VENKATESWARA PRANADANA TRUST With a noble aim to provide free medication to the poor patients afflicted with life threatening diseases related to heart, kidneys, brain etc. TTD has started Sri Venkateswara Pranadana Trust. Donate liberally to S V Pranadanam. Donors will get Income Tax Exemption Sec 80G 3. SRI VENKATESWARA GOSAMRAKSHANA TRUST With an aim to protect the cow and emphasize its spiritual importance, TTD has established Gosamrakshana Shala in 1956 and established S V Gosamrakshna Trust in 2002. Contribute liberally towards this Trust and adopting animals in the Gosala. Donor will get Income Tax Exemption under Sec80G 4. SRI VENKATESWARA VIDYA DANA TRUST TTD introduced S V Vidya Dana Trust in 2008 with an aim to sanction scholarships to 1000 meritorious below poverty line students who are studying in Govt, ZP,Municipal Corporation, Municipality, private aided and TTD-run schools alone. -

DEEP END REPORT 36 General Practice in the Time of Covid-19 June 2020

DEEP END REPORT 36 General Practice in the time of Covid-19 12 general practitioners in Deep End practices in Glasgow and Edinburgh report and reflect on their experience of how the Covid-19 pandemic has affected patients and practices. As the pandemic continues and the economic consequences unfold, the report also considers the future implications. June 2020 1 Executive Summary : General Practice in the Time of Covid-19 12 general practitioners in Deep End practices in Glasgow and Edinburgh report and reflect on their experience of how the Covid-19 pandemic has affected patients and practices during May 2020, and on the implications for what happens next. General practice during the pandemic • General practice adapted rapidly and universally in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, using remote consultations for initial triage and keeping in touch with shielded patients. • Practice teams proved agile, resilient, enterprising and committed. • Usual general practice activities have been reduced (routine consultations), some significantly (home visits), while others have stopped (practice nurse triage). • Remote consulting, by phone or video, works for some types of patients, problems and purposes. The best uses of these technologies need to be established. • Community link workers have been “invaluable” in contacting vulnerable patients, meeting their needs and making connections with community resources for health. • PPE supplies were inadequate at the outset. Many practices bought their own. Eventually these problems were resolved. • Symptomatic staff were frustrated at the delay in getting a Covid-19 test and obtaining the result at the beginning of the outbreak. Concerns • The NHS has protected itself by putting much of its work on hold. -

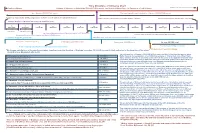

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

Kali-Yuga of Brotherhood

I.S.I.S. Foundation The Messenger of Light The activities of the I.S.I.S. Foundation are based on: 1. The essential unity of all that exists. ® 2. By reason of this unity: brotherhood as a fact in nature. 3. Respect for everyone’s free will (when applied from this idea of universal brotherhood). 4. Respect for everyone’s freedom to build up their own view of life. 5. To support the developing of everyone’s own view of life and its application in daily practice. LuciferFor seekers of Truth Current topics viewed in the light of the Ancient Wisdom or Theo-sophia — the common source of all great world religions, philosophies and sciences Why this journal is called Lucifer Theosophy’s rightful place Lucifer literally means Bringer of Light. Each culture in the East and West has his bringers of light: inspiring individuals who give the initial impulse to spiritual growth and social reform. Spiritual progress in They stimulate independent thinking and living with a profound awareness Kali-Yuga of brotherhood. These bringers of light have always been opposed and slandered by the Repentance works? establishment. But there are always those who refuse to be put off by these slanderers, and start examining the wisdom of the bringers of light in an Brotherhood and open-minded and unprejudiced way. sisterhood? For these people this journal is written. “… the title chosen for our magazine is as much associated with divine ideas From Higgs-particle as with the supposed rebellion of the hero of Milton’s Paradise Lost … to Theosophia We work for true Religion and Science, in the interest of fact as against fiction and prejudice. -

Brahman, Atman and Maya

Sanatana Dharma The Eternal Way of Life (Hinduism) Brahman, Atman and Maya The Hindu Way of Comprehending Reality and Life Brahman, Atman and Maya u These three terms are essential in understanding the Hindu view of reality. v Brahman—that which gives rise to maya v Atman—what each maya truly is v Maya—appearances of Brahman (all the phenomena in the cosmos) Early Vedic Deities u The Aryan people worship many deities through sacrificial rituals: v Agni—the god of fire v Indra—the god of thunder, a warrior god v Varuna—the god of cosmic order (rita) v Surya—the sun god v Ushas—the goddess of dawn v Rudra—the storm god v Yama—the first mortal to die and become the ruler of the afterworld The Meaning of Sacrificial Rituals u Why worship deities? u During the period of Upanishads, Hindus began to search for the deeper meaning of sacrificial rituals. u Hindus came to realize that presenting offerings to deities and asking favors in return are self-serving. u The focus gradually shifted to the offerings (the sacrificed). u The sacrificed symbolizes forgoing one’s well-being for the sake of the well- being of others. This understanding became the foundation of Hindu spirituality. In the old rites, the patron had passed the burden of death on to others. By accepting his invitation to the sacrificial banquet, the guests had to take responsibility for the death of the animal victim. In the new rite, the sacrificer made himself accountable for the death of the beast. -

Transnational Neo-Nazism in the Usa, United Kingdom and Australia

TRANSNATIONAL NEO-NAZISM IN THE USA, UNITED KINGDOM AND AUSTRALIA PAUL JACKSON February 2020 JACKSON | PROGRAM ON EXTREMISM About the Program on About the Author Extremism Dr Paul Jackson is a historian of twentieth century and contemporary history, and his main teaching The Program on Extremism at George and research interests focus on understanding the Washington University provides impact of radical and extreme ideologies on wider analysis on issues related to violent and societies. Dr. Jackson’s research currently focuses non-violent extremism. The Program on the dynamics of neo-Nazi, and other, extreme spearheads innovative and thoughtful right ideologies, in Britain and Europe in the post- academic inquiry, producing empirical war period. He is also interested in researching the work that strengthens extremism longer history of radical ideologies and cultures in research as a distinct field of study. The Britain too, especially those linked in some way to Program aims to develop pragmatic the extreme right. policy solutions that resonate with Dr. Jackson’s teaching engages with wider themes policymakers, civic leaders, and the related to the history of fascism, genocide, general public. totalitarian politics and revolutionary ideologies. Dr. Jackson teaches modules on the Holocaust, as well as the history of Communism and fascism. Dr. Jackson regularly writes for the magazine Searchlight on issues related to contemporary extreme right politics. He is a co-editor of the Wiley- Blackwell journal Religion Compass: Modern Ideologies and Faith. Dr. Jackson is also the Editor of the Bloomsbury book series A Modern History of Politics and Violence. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Program on Extremism or the George Washington University. -

Notes on Hinduism

NOTES ON HINDUISM Note: Many "Hindus" prefer the name "Sanatana Dharma" (Eternal Truth) for their religion. "Hinduism" – meaning "the religions of the Indians" – is a term that was probably introduced by the British in the 18th century. BASIC BELIEFS The origins of Hinduism have been dated as early as 3000 BC. It is a rich religious and cultural tradition containing and encompassing many diverse and even conflicting beliefs and practices. While there is, in Hinduism, no rigidly enforced set of doctrines or dogmas, there is a configuration of themes and claims that represents a generally agreed upon Hindu belief system. 1. Hindus believe in a single Supreme Reality known as Brahman, which is the ultimate source of the cosmos and all things in it. Some Hindus consider Brahman to be God, a savior to be loved and worshiped; others think of it as a Transcendent and Unmanifest Absolute, a Ground of Being, without any of the characteristics traditionally attributed to "God" by religious believers. The three main characteristics of Brahman are sat (absolute being), chit (absolute consciousness and knowledge), and ananda (absolute bliss). The Supreme Reality in its transcendent, absolute, and unmanifest essence is called Nirguna-Brahman (unrevealed, "without attributes"); in its revealed or manifest nature, it is called Saguna-Brahman ("with attributes"). There are three major manifestations of Saguna-Brahman: Brahma (God the Creator), Vishnu (God the Preserver) and Shiva (God the Destroyer). Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva (the Trimurti, the "three forms" of Brahman) are not really three distinct deities in addition to the supreme Brahman; rather, they are the three ways in which Brahman is manifested in the cosmos and in which Brahman appears to human consciousness. -

Management Lessons from Advaita Bhavesh a Kinkhabwala

143 Management Lessons from Advaita Bhavesh A Kinkhabwala Introduction Acharya Shankara is a thorough, outright one. he word ‘Advaita’ is very beautiful. It As indicated by him, whatever is, is Brahman. Tliterally means ‘non-dual’. Dvaita means Brahman itself is totally homogeneous. All dis- ‘dual’ and the prefix ‘a’ negates the exist- tinctions and plurality are deceptive.3 ence of duality so, there is no ‘two’ but, ‘one’. It Dualism, Dvaita; qualified monism, Vish- could be simpler, if we said ‘one’, but then, the ishtadvaita; and Monism, Advaita; are the three next question would be, is there ‘two’; so by say- different fundamental schools of metaphysical ing non-dual, it conveys the clear and firm mes- ideas. They are altogether different stages to the sage of being just one, that is non-dual. final stage of the ultimate Truth, namely,para- Acharya Shankara’s ‘philosophical stand- brahma. They are the steps on the stepping stool point can be tried to be summed up in a sin- of yoga. They are not in any manner conflicting gle word “Advaita”—NonDuality. The objective but, in actuality, they are complementary to one of Advaita is to is to make an individual under- another. These stages are amicably orchestrated in stand his or her fundamental (profound) char- an evaluated arrangement of spiritual experiences. acter with the preeminent realty [sic] “Nirakar Dualism, qualified monism, pure monism—all Brahm” and reality that there is no “two” yet one these come full circle inevitably in the Advaita and only. Advaita shows us to see the substance Vedantic acknowledgement of the Absolute or of oneself in each one and that nobody is sep- the supra-normal trigunatita ananta Brahman.