Freaks and Magic: the Freakification of Magical Creatures in Harry Potter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harry's True Mentor and His Moral Struggle in J. K. Rowling's Harry

Harry’s True Mentor and His Moral Struggle in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Series Mrs. K. Nagamani, M.A., Ph.D. Research Scholar (English) ==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 13:8 August 2013 ==================================================================== Courtesy: http://www.harleysvillebooks.com/celebrate-all-things-harry-potter Silent Language Spoken words always carry significant meaning, but sometimes unspoken silence becomes more meaningful and powerful. Implicit suggestions hold nuances of meaning in literature. Flat, static characters are always explicit and there is no mystery in them to be fathomed. Complex characters, on the other hand, are unpredictable and thereby become more interesting and challenging. Severus Snape, in Harry Potter series definitely falls under the latter category. He, in the author’s own words, is “a gift of a character” (http://web.archive.org/web/20110726135809/http://www.half-bloodprince.org/snape_jkr.php). Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 13:8 August 2013 Mrs. K. Nagamani, M.A., Ph.D. Research Scholar (English) Harry’s True Mentor and His Moral Struggle in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Series 471 A Complex Multifaceted Teacher The Potions Instructor, Head of the Slytherin House is arguably the most complex and multifaceted teacher at Hogwarts. He is clever and cunning; intelligent and has a keen analytical mind. The progress of the series shows him as a more layered character evolving from a malicious and prejudiced teacher to one of considerable complexity and moral ambiguity. The immediate impression on beholding him is of fear and scorn. With the combination of his robes, his attitude, behavior and his classroom décor, he employs pedagogy of fear and intimidation. -

Harry Potter, Lord Voldemort, and the Importance of Resilience by Emily

Harry Potter, Lord Voldemort, and the Importance of Resilience by Emily Anderson A thesis presented to the Honors College of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the University Honors College Spring 2017 Harry Potter and the Importance of Resilience by Emily Anderson APPROVED: ____________________________ Dr. Martha Hixon, Department of English Dr. Maria Bachman, Chair, Department of English __________________________ Dr. Teresa Davis, Department of Psychology ___________________________ Dr. Philip E. Phillips, Associate Dean University Honors College ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Hixon for her knowledge and endless support of this thesis even when finishing seemed impossible. I would also like to thank my family for the countless hours spent listening to the importance of resilience in Harry Potter and for always being there to edit, comment on, and support this thesis. i ABSTRACT Literature and psychology inadvertently go hand in hand. Authors create characters that are relatable and seem real. This thesis discusses the connection between psychology and literature in relation to the Harry Potter series. This thesis focuses on the importance of resilience or lack thereof in the protagonist, Harry, and the antagonist Voldemort. Specifically, it addresses resilience as a significant difference between the two. In order to support such claims, I will be using Erik Erikson’s Theory of Psycho-Social Development to analyze the struggles and outcomes of both Harry and Voldemort in relation to resilience and focus on the importance of strong, supportive relationships as a defining factor in the development of resilience. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………......i ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………….ii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... -

Fantastic Beasts and the Fear of Fascism

Fantastic Beasts and the Fear of Fascism Aalborg University 2019 Master’s Thesis -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Christina Dam Simonsen Supervisor: Mia Rendix Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Theory ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Biography ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Fascism .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Speeches ...................................................................................................................................................... 16 Comparison.................................................................................................................................................. 20 Analysis ............................................................................................................................................................ 21 J.K. -

Co-Creating Harry Potter: Children’S Fan-Play, Folklore and Participatory Culture

CO-CREATING HARRY POTTER: CHILDREN’S FAN-PLAY, FOLKLORE AND PARTICIPATORY CULTURE by © Contessa Small A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland April 2015 St. John’s Newfoundland Abstract A number of scholars have argued that children’s traditional artifacts and play are being replaced by media culture objects and manipulated by corporations. However, while companies target and exploit children, it is problematic to see all contemporary youth or “kid” culture as simply a product of corporate interests. This thesis therefore explores children’s multivocal fan-play traditions, which are not only based on corporation interests, but also shaped by parents, educators and children themselves. The Harry Potter phenomenon, as a contested site where youth struggle for visibility and power, serves as the case study for this thesis. Through the examination of an intensely commercialized form of children’s popular culture, this thesis explores the intricate web of commercial, hegemonic, folk, popular and vernacular cultural expressions found in children’s culture. This thesis fits with the concerns of participatory literacy which describes the multiple ways readers take ownership of reading and writing to construct meaning within their own lives. Due to the intense corporate and adult interests in Pottermania, children have continually been treated in the scholarly literature as passive receptors -

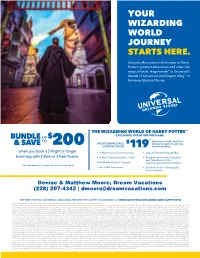

Your Wizarding World Journey Starts Here

YOUR WIZARDING WORLD JOURNEY STARTS HERE. Step into the excitement of some of Harry Potter's greatest adventures and enter two magical lands: Hogsmeade™ in Universal's Islands of Adventure and Diagon Alley™ in Universal Studios Florida. THE WIZARDING WORLD OF HARRY POTTER™ ^ EXCLUSIVE VACATION PACKAGE BUNDLE UP $ TO per person, per night, based on a & SAVE VACATION PACKAGE $ family of four with a 5-night stay, 200 STARTING FROM 119 limited availability. when you book a 2-Night or longer • 5-Night Hotel Accommodations • Special Themed Keepsake Box§ hotel stay with 2-Park or 3-Park Tickets. • 2-Park 5-Day Park-to-Park Ticket1 • Breakfast at the Leaky Cauldron™ and Three Broomsticks™ • $75 Bundle & Save^ Discount (one per person at each location) ^Savings based on 7-night stay. Restrictions apply. • Early Park Admission2 • Shutterbutton’s™ Photography Studio Session8 Denise & Matthew Moore, Dream Vacations (228) 207-4342 | [email protected] BEFORE VISITING UNIVERSAL ORLANDO, REVIEW THE SAFETY GUIDELINES AT WWW.UNIVERSALORLANDO.COM/SAFETYINFO WIZARDING WORLD and all related trademarks, characters, names, and indicia are © & ™ Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. Publishing Rights © JKR. (s21) All prices, package inclusions & options are subject to availability and to change without notice and additional restrictions may apply. Errors will be corrected where discovered, and Universal Orlando and Universal Parks & Resorts Vacations reserve the right to revoke any stated offer and to correct any errors, inaccuracies or omissions, whether such error is on a website or any print or other advertisement relating to these products and services. ^Bundle and Save offer discount only applies to Universal Orlando vacation packages purchased on Universal Parks & Resorts Vacations websites (UniversalOrlando.com, UniversalOrlandoVacations.com, VAXVacationAccess.com/UPRV), the Universal Orlando Guest Contact Center or through travel agencies registered to sell vacation packages with Universal Parks & Resorts Vacations. -

Wizarding Hierarchy

English University of Iceland School of Humanities English Wizarding Hierarchy A Portrayal of Discrimination and Prejudice in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels B.A. Thesis Sigríður Eva Þorsteinsdóttir Kt.: 020696-3549 Supervisor: Valgerður Guðrún Bjarkadóttir May 2018 Abstract This paper explores how the Harry Potter novels by J.K. Rowling touches on the subject of discrimination and general prejudice against minority groups throughout the history of mankind. Though there are many minority groups in the novels, only a few will be discussed. Each of them will be compared to minority groups that faces prejudice in the real world. The paper further examines the effect discrimination has on the wizarding world and the struggle that wizards have to face to break from old habits, such as the enslavement of house-elves and their ongoing quarrels with goblins and other non-human creatures. The history of these feuds will be discussed as well as possible ways of mending the relationship between wizards and the minority groups. Oppression and abuse towards these minority groups are parts of the daily life of wizards and has been for centuries. Likewise, there will a focus on the prejudice werewolves face and how they mirror HIV infected people. In order to compare werewolves and people with HIV, a series of articles and studies on attitude towards diseases such as HIV/AIDS will be analyzed. The paper will also include a discussion about a few characters from the series that in some way are connected to minority groups: Hermione Granger, Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, Dolores Umbridge, Lord Voldemort, Dobby the house- elf, and lastly the werewolf Remus Lupin. -

J. K. Rowling´S Novels and Their Film Versions Romány J

Univerzita Hradec Králové Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury a oddělení francouzského jazyka J. K. Rowling´s Novels and their Film versions Romány J. K. Rowlingové a jejich filmové verze Bakalářská práce Autor: Lucie Olivová Studijní program: B7310 – Filologie Studijní obor: Cizí jazyky pro cestovní ruch - anglický jazyk Cizí jazyky pro cestovní ruch - francouzský jazyk Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Patricia Ráčková, Ph.D. Hradec Králové 2015 UNIVERZITA HRADEC KRÁLOVÉ Pedagogická fakulta Akademický rok: 2015/2016 ZÁDÁNÍ BAKALÁŘSKÉ PRÁCE Jméno a příjmení: Lucie Olivová Osobní číslo: P121327 Studijní program: B7310 Filologie Studijní obory: Cizí jazyky pro cestovní ruch - anglický jazyk Cizí jazyky pro cestovní ruch - francouzský jazyk Název tématu: Romány J. K. Rowlingové a jejich filmové verze Zadávající katedra: Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Zásady pro vypracování: Práce se zaměří na dva texty J. K. Rowlingové, první díl série o Harry Potterovi, The Philosopher´s Stone, a poslední text, The Deathly Hallows. Věnuje se zejména aspektu postav a prostředí, poukáže na jejich specifika a vývoj. Dále se pokusí porovnat pojetí postav a prostředí v uvedených románech a jejich filmových verzích; rovněž si povšimne využití původního textu a dialogů v obou filmech. Rozsah grafických prací: Rozsah pracovní zprávy: Seznam odborné literatury: Vedoucí bakalářské práce: PhDr. Patricia Ráčková, Ph.D. Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Datum zadání bakalářské práce: 10. prosince 2013 Termín odevzdání bakalářské práce: 5. června 2015 doc. PhDr. Pavel Vacek, Ph.D Mgr. Olga Vraštilová, M.A., Ph.D. děkan vedoucí katedry dne Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracovala (pod vedením vedoucí bakalářské práce) samostatně a uvedla jsem všechny použité prameny a literaturu. -

Lord Voldemort's Request

Harry Potter and the Sacred Text Book 6, Chapter 20: Lord Voldemort’s Request - Good Will Vanessa: Chapter 20 Lord Voldemort’s Request Vanessa: (reading aloud) Harry and Ron left the hospital wing first thing on Monday morning, returned to full health by the ministrations of Madame Pomfrey and now able to enjoy the benefits... I’m Vanessa Zultan. Casper: I’m Casper ter Kuile. Vanessa: And this is Harry Potter and the Sacred Text. Casper: This week’s episode is our last one before we take a two week holiday break. So, if you’ve been running behind, now is your chance to catch up. And we’ve got less than a week left to donate to RAICES, as part of our amazing “Don’t Be A Dursley” campaign. We have set goals, you have beaten them. We’ve set another goal, you’ve beaten it again. It’s been amazing to watch how our entire community has come together to support this issue. And we’re so, so grateful. Thanks to anyone who’s got a final donation to make in this last week. Vanessa: Also, Casper, did you know that my favorite director is a man named Richard Linklater? And that he lives in a city named Austin, Texas? (Casper laughing) And I am curious if he is a member of our local group there. Casper: They are the amazing Longhorn Snorkacks and it’s run by Caitlin Mimms. And if you wanna join our local group in Austin, so to HarryPotterSacredText.com/groups where you can find their info as well as more than 55 groups around the world now. -

“Decreasing World Suck”

Dz dzǣ Fan Communities, Mechanisms of Translation, and Participatory Politics Neta Kligler-Vilenchik A Case Study Report Working Paper Media, Activism and Participatory Politics Project AnnenBerg School for Communication and Journalism University of Southern California June 24, 2013 Executive Summary This report describes the mechani sms of translation through which participatory culture communities extend PHPEHUV¶cultural connections toward civic and political outcomes. The report asks: What mechanisms do groups use to translate cultural interests into political outcomes? What are challenges and obstacles to this translation? May some mechanisms be more conducive towards some participatory political outcomes than others? The report addresses these questions through a comparison between two groups: the Harry Potter Alliance and the Nerdfighters. The Harry Potter Alliance is a civic organization with a strong online component which runs campaigns around human rights issues, often in partnership with other advocacy and nonprofit groups; its membership skews college age and above. Nerdfighters are an informal community formed around a YouTube vlog channel; many of the pDUWLFLSDQWVDUHKLJKVFKRRODJHXQLWHGE\DFRPPRQJRDORI³GHFUHDVLQJZRUOGVXFN.´ These two groups have substantial overlapping membership, yet they differ in their strengths and challenges in terms of forging participatory politics around shared cultural interests. The report discusses three mechanisms that enable such translation: 1. Tapping content worlds and communities ± Scaffolding the connections that group members have through their shared passions for popular culture texts and their relationships with each other toward the development of civic identities and political agendas. 2. Creative production ± Encouraging production and circulation of content, especially for political expression. 3. Informal discussion ± Creating and supporting spaces and opportunities for conversations about current events and political issues. -

HARRY POTTER in TURKEY the SOCIOCULTURAL FRAMEWORK of TRANSLATION in a GLOBAL CONTEXT Thesis Submitted to the Institute For

HARRY POTTER IN TURKEY THE SOCIOCULTURAL FRAMEWORK OF TRANSLATION IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT Thesis submitted to the Institute for Graduate Studies in the Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Translation by Merlin Özkan Boğaziçi University 2009 Thesis Abstract Merlin Özkan, “Harry Potter in Turkey: The Sociocultural Framework of Translation in a Global Context” This study focuses on the sociocultural framework of translational phenomena which governs the selection, production and reception processes. In this light, the external forces effective in the creation of a translated text, how these forces influence the adoption of translation strategies and the impact of translation as a cultural product are analyzed. The implications of cultural exchange through translation in a globalized background are studied in line with the analysis of the interactional character between broader social structures with all its agencies and their effect on the functional mechanisms of translation markets, the publishing industry and the procedural stages of translation. Itamar Even-Zohar’s polysystem theory, Pierre Bourdieu’s relevant concepts of cultural production and circulation model, Gideon Toury’s concept of norms and Lawrence Venuti’s discourse on a cultural and political agenda are explored and questioned in terms of their sociological implications. The applicable aspects of these theoretical approaches are put into test to analyze the implications of the Harry Potter translations in the Turkish target culture and the intercultural relations of translations across various cultural settings. The analysis of the case study has shown that the translations are initially conditioned by the macro clusters of social structures, such as the workings of the publishing industry, the politics of media concerns and specific social, cultural and economic concerns of the decision- makers particular to the target culture. -

Issues with Racism, Classism, and Ideology in Harry Potter Tiffany L

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 5-2015 Not So Magical: Issues with Racism, Classism, and Ideology in Harry Potter Tiffany L. Walters [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Walters, Tiffany L., "Not So Magical: Issues with Racism, Classism, and Ideology in Harry Potter" (2015). All NMU Master's Theses. 42. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/42 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. NOT SO MAGICAL: ISSUES WITH RACISM, CLASSISM, AND IDEOLOGY IN HARRY POTTER By Tiffany Walters THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Office of Graduate Education and Research May 2015 SIGNATURE APPROVAL FORM Not So Magical: Issues with Racism, Classism and Ideology in Harry Potter This thesis by Tiffany Walters is recommended for approval by the student’s thesis committee in the Department of English and by the Assistant Provost of Graduate Education and Research. Committee Chair: Dr. Kia Jane Richmond Date First Reader: Dr. Ruth Ann Watry Date Second Reader: N/A Date Department Head: Dr. Robert Whalen Date Dr. Brian D. Cherry Assistant Provost of Graduate Education and Research ABSTRACT NOT SO MAGICAL: ISSUES WITH RACISM, CLASSISM, AND IDEOLOGY IN HARRY POTTER By Tiffany Walters Although it is primarily a young adult fantasy series, the Harry Potter books are also focused on the battle against racial purification and the threat of a strictly homogenous magical society. -

An Exploration of JK Rowling's Social and Political Agenda in the Harry

Vollmer UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research X (2007) Harry’s World: An Exploration of J.K. Rowling’s Social and Political Agenda in the Harry Potter Series Erin Vollmer Faculty Sponsor: Richard Gappa, Department of English ABSTRACT Over the years, the Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling has grown in popularity, becoming one of the most read and most criticized pieces of children’s literature to date. Interestingly, the series has not only gained popularity with children, but also their adult counterparts. As a result of its adult success, Harry Potter has attracted more and more scholars to pursue serious literary analysis, most frequently exploring themes such as death and religion. However, the focus of this research is on the intertextual parallels of the numerous hierarchical structures found in the Harry Potter series, examining how these hierarchies develop the social and racial themes in the story and vice versa. A further purpose is to determine if there is a correlation between the power structures found in the series and our own, drawing on secondary criticisms and theory for support. Above all, although the series should not be reduced to “this versus that,” there is sufficient evidence to argue that a conflict of materialistic versus altruistic values is at work in the Harry Potter series. Therefore, the examination of race, hierarchy, and power assists in the recognition of the social and political systems at work in the series. Keywords: J.K. Rowling, Hierarchy, Materialism INTRODUCTION When a skinny boy with black hair, green eyes, and a telltale scar appeared on the scene in 1997, nobody could have predicted the significant impact this seemingly insignificant boy would have on the world.