An Investigation of Theory of Mind and Empathy in the Harry Potter Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone

NAME: # DATE: Reading Packet: HP Sorcerer’s Stone Harry Potter and The Sorcerer’s Stone J. K. Rowling Study Guide/Quiz Questions - Harry Potter Multiple Choice Format Chapter One 1. What did the reader learn about Mr. and Mrs. Dursley in the book’s first paragraph? a. They were wizards in disguise. b. They were “perfectly normal” people. c. They were really named Potter. d. They were descended from trolls. 2. What did Mr. Dursley do for a living? a. He was a big-time politician. b. He was a fireman. c. He was the director of Grunnings, a firm which made drills. d. He was the supervisor of a plastics manufacturing firm. 3. What big secret did Mr. and Mrs. Dursley want to keep? a. They wanted to keep their son a secret. b. They wanted to keep secret the fact that they were gypsies. c. They wanted to keep their embezzlement from the bank a secret. d. They wanted to keep Mrs. Dursley’s sister a secret. 4. What was the first unusual thing that Mr. Dursley thought he saw as he left for work? a. He thought he saw a huge dog chasing its tail. b. He thought he saw a storm coming up. c. He thought he saw a cat reading a map. d. He thought he saw Harry Potter crossing the street ahead of him. 5. What was unusual about the people Mr. Dursley saw while he waited in a traffic jam? a. They were muttering about Mrs. Dursley. b. The people were strangely dressed in cloaks. -

Wands Or Quills? Lessons in Pedagogy from Harry Potter

Summer/ Fall THE CEA FORUM 2015 Wands or Quills? Lessons in Pedagogy from Harry Potter Melissa C. Johnson Virginia Commonwealth University “The real world, then, becomes somewhat illuminated by these characters who can span both worlds. For example, teachers at Hogwarts can be imaginative and compassionate; they are also flighty, vindictive, dim-witted, indulgent, lazy, frightened and frightening. Students are clever, kind, weak, cruel, snobbish. Lessons are inspiring and tedious—as in the best and worst of real schools” (317). – Roni Natov from “Harry Potter and the Extraordinariness of the Ordinary” When I first began teaching first-year college students in 1994 as a graduate student, I was in my mid-twenties, not much older than my students, and a product of the same popular culture. I frequently made reference to that pop culture and used it for comparison, analysis, and discussion to help my 75 www.cea-web.org Summer/ Fall THE CEA FORUM 2015 students develop their thinking and writing skills. Every year, I grew older and a new class of eighteen- and nineteen-year-olds began their first year at the university or college at which I was teaching. The popular culture of my teens and twenties became a part of the great depth and breadth of events encapsulated in the common student phrase “back in the day,” as the double atrocities of “reality” television and movies based on toys began to capture my students’ interests and as the World Wide Web further atomized those interests. Slowly, but surely, I found myself less skilled and less successful at using pop culture in the classroom as a touchstone or an example. -

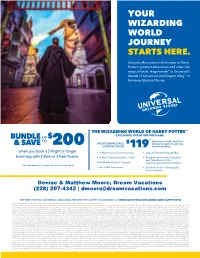

Your Wizarding World Journey Starts Here

YOUR WIZARDING WORLD JOURNEY STARTS HERE. Step into the excitement of some of Harry Potter's greatest adventures and enter two magical lands: Hogsmeade™ in Universal's Islands of Adventure and Diagon Alley™ in Universal Studios Florida. THE WIZARDING WORLD OF HARRY POTTER™ ^ EXCLUSIVE VACATION PACKAGE BUNDLE UP $ TO per person, per night, based on a & SAVE VACATION PACKAGE $ family of four with a 5-night stay, 200 STARTING FROM 119 limited availability. when you book a 2-Night or longer • 5-Night Hotel Accommodations • Special Themed Keepsake Box§ hotel stay with 2-Park or 3-Park Tickets. • 2-Park 5-Day Park-to-Park Ticket1 • Breakfast at the Leaky Cauldron™ and Three Broomsticks™ • $75 Bundle & Save^ Discount (one per person at each location) ^Savings based on 7-night stay. Restrictions apply. • Early Park Admission2 • Shutterbutton’s™ Photography Studio Session8 Denise & Matthew Moore, Dream Vacations (228) 207-4342 | [email protected] BEFORE VISITING UNIVERSAL ORLANDO, REVIEW THE SAFETY GUIDELINES AT WWW.UNIVERSALORLANDO.COM/SAFETYINFO WIZARDING WORLD and all related trademarks, characters, names, and indicia are © & ™ Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. Publishing Rights © JKR. (s21) All prices, package inclusions & options are subject to availability and to change without notice and additional restrictions may apply. Errors will be corrected where discovered, and Universal Orlando and Universal Parks & Resorts Vacations reserve the right to revoke any stated offer and to correct any errors, inaccuracies or omissions, whether such error is on a website or any print or other advertisement relating to these products and services. ^Bundle and Save offer discount only applies to Universal Orlando vacation packages purchased on Universal Parks & Resorts Vacations websites (UniversalOrlando.com, UniversalOrlandoVacations.com, VAXVacationAccess.com/UPRV), the Universal Orlando Guest Contact Center or through travel agencies registered to sell vacation packages with Universal Parks & Resorts Vacations. -

Wizarding Hierarchy

English University of Iceland School of Humanities English Wizarding Hierarchy A Portrayal of Discrimination and Prejudice in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels B.A. Thesis Sigríður Eva Þorsteinsdóttir Kt.: 020696-3549 Supervisor: Valgerður Guðrún Bjarkadóttir May 2018 Abstract This paper explores how the Harry Potter novels by J.K. Rowling touches on the subject of discrimination and general prejudice against minority groups throughout the history of mankind. Though there are many minority groups in the novels, only a few will be discussed. Each of them will be compared to minority groups that faces prejudice in the real world. The paper further examines the effect discrimination has on the wizarding world and the struggle that wizards have to face to break from old habits, such as the enslavement of house-elves and their ongoing quarrels with goblins and other non-human creatures. The history of these feuds will be discussed as well as possible ways of mending the relationship between wizards and the minority groups. Oppression and abuse towards these minority groups are parts of the daily life of wizards and has been for centuries. Likewise, there will a focus on the prejudice werewolves face and how they mirror HIV infected people. In order to compare werewolves and people with HIV, a series of articles and studies on attitude towards diseases such as HIV/AIDS will be analyzed. The paper will also include a discussion about a few characters from the series that in some way are connected to minority groups: Hermione Granger, Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, Dolores Umbridge, Lord Voldemort, Dobby the house- elf, and lastly the werewolf Remus Lupin. -

EXTENDED ESSAY English B

EXTENDED ESSAY English B: Category 2B November 2019 session Evolution and development of the character of Ron Weasley from the saga of Harry Potter by JK Rowling To what extent the family and social context of the character Ron Weasley of the saga of Harry Potter by JK Rowling influenced in the development of his personality? Candidate Code number: 004727 - 0009 Word count: 4000 Supervisor: Gisela Riccio Ipanaque Chiclayo, Peru. Index: Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………………1 First Chapter ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 1.1 Ron´s family context ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 1.2 Family influence ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 1.2.1 Parents ……………………………………………………………………………..……………………………………….4 1.2.2 Siblings ………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………………….6 Second Chapter ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….....8 2.1 Social context …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.1.1 Ron´s social context …………………………………………………………………………..…………………...…..8 2.1.2 Social context influence ……………………………………………………………………………….…………….10 2.1.2.1 Peers …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 Third Chapter ………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………...13 3.1 Evolution of Ron`s personality …………………………………………………………………………………….…13 Conclusions ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….15 References …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………16 1 Introduction There isn´t a secret that our development as a person is due to the constant influence that our environment gives to us. When we are -

Performance and Participation in Media Fandom Sebastiaan Gorissen University of New Mexico - Main Campus

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Communication ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-4-2017 Common among wizards, popstars, and cowboys: Performance and participation in media fandom Sebastiaan Gorissen University of New Mexico - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cj_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Gorissen, Sebastiaan. "Common among wizards, popstars, and cowboys: Performance and participation in media fandom." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cj_etds/101 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sebastiaan Gorissen Candidate Communication & Journalism Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Dr. David Weiss , Chairperson Dr. Judith Hendry , Chairperson Dr. Richard Schaefer i COMMON AMONG WIZARDS, POPSTARS, AND COWBOYS: PERFORMANCE AND PARTICIPATION IN MEDIA FANDOM BY SEBASTIAAN GORISSEN BACHELOR OF ARTS | MEDIA & CULTURE UNIVERSITY OF AMSTERDAM 2013 MASTER OF ARTS | FILM STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF AMSTERDAM 2014 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS COMMUNICATION The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2017 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge Dr. Judith Hendry and Dr. David Weiss, my advisors and committee chairs, for their invaluable support. Their insights, comments, questions, and critiques have been instrumental in crafting this thesis, and helped me strive for improvement with every draft of every chapter. -

The Unsung Hero of Harry Potter: Neville Longbottom

1 Jaime Feathers The Unsung Hero of Harry Potter: Neville Longbottom The bulk of J.K. Rowling’s magical series chronicles the quests and adventures of the obvious hero of the books, Harry Potter. We wouldn’t expect anything less. It’s also no surprise that the vast majority of the heroism displayed in the story resides firmly within Harry’s grasp. Again, we wouldn’t expect anything less. What we might not expect is that Neville Longbottom, a character who fumbles and bumbles his way through the entire series, is also a hero. Yet that’s exactly what Neville is. Just as Dumbledore says in Sorcerer’s Stone, while speaking of Neville, that “there are all kinds of courage” (306), there are also all kinds of heroism. Neville’s isn’t the obvious, grandiose kind. It is understated and subtle, found hidden within his determination to overcome his blundering nature and his refusal to allow other people’s unfavorable opinions of him to define him. While Harry’s heroism is exciting and entertaining, it’s also larger than life. It is Neville’s heroism that presents itself in an attainable way, giving it the potential to truly resonate within the life of a child. If readers were asked which Harry Potter character they’d most like to emulate, it’s no secret that Neville Longbottom would fall pretty far down on the list. The majority of scenes containing Neville are enough to make anybody cringe. He melts a cauldron in Potions class and blisters himself and his classmates (Sorcerer’s Stone 139). -

WIZARD QUICK DRAW CHALLENGE Cut out the Words Below, Fold Them up and Put Them in a Hat Or Container

22 More Wizarding Activities YOU MAY PHOTOCOPY THIS SHEET WIZARD QUICK DRAW CHALLENGE Cut out the words below, fold them up and put them in a hat or container. Divide your guests into teams of two or more. Each turn, one member of the team selects a card and has to draw the item on a flipchart or large piece of paper, for the rest of their team to guess. Award 10 house points for each correct answer guessed. Nimbus Two Sorting Hat Thousand Cat Toad Broomstick Hogwarts Owl Wand Cauldron Express Flying Pumpkin Scar Portrait Motorbike Golden Ghost Rat Dragon Snitch Chocolate Diagon Butterbeer Frog Alley harrypotterbooknight.com #HarryPotterBookNight 25 More Wizarding Activities YOU MAY PHOTOCOPY THIS SHEET WIZARD WORDSEARCH Can you search out these characters from the Harry Potter books in the grid below? Words can read up, down, across, backwards and diagonally. S E V E R U S S N A P E H I F O A L E B E C L R A D R D L V U N E D H O R U E I E D O N D O A D R D D E U I E I A B G E Y L P F M S R M G B R L P E K R U M B E O Y I B O Y E H O I J L M R D M T H K T O N K S A U T U T N E V I L L E L C S D E C R O O K S H A N K S R M A L F O Y C R E P P H E D W I G I N N Y M N CROOKSHANKS HARRY POTTER REMUS DOBBY HERMIONE RON DUDLEY KRUM SEVERUS SNAPE DUMBLEDORE LUNA SIRIUS BLACK FRED MALFOY TOM RIDDLE GINNY NEVILLE TONKS HAGRID PEEVES VOLDEMORT HEDWIG PERCY harrypotterbooknight.com #HarryPotterBookNight 28 More Wizarding Activities YOU MAY PHOTOCOPY THIS SHEET WIZARDING WORD PLAY Anagrams and riddles play a big part in Harry and his friends’ adventures. -

An Exploration of JK Rowling's Social and Political Agenda in the Harry

Vollmer UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research X (2007) Harry’s World: An Exploration of J.K. Rowling’s Social and Political Agenda in the Harry Potter Series Erin Vollmer Faculty Sponsor: Richard Gappa, Department of English ABSTRACT Over the years, the Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling has grown in popularity, becoming one of the most read and most criticized pieces of children’s literature to date. Interestingly, the series has not only gained popularity with children, but also their adult counterparts. As a result of its adult success, Harry Potter has attracted more and more scholars to pursue serious literary analysis, most frequently exploring themes such as death and religion. However, the focus of this research is on the intertextual parallels of the numerous hierarchical structures found in the Harry Potter series, examining how these hierarchies develop the social and racial themes in the story and vice versa. A further purpose is to determine if there is a correlation between the power structures found in the series and our own, drawing on secondary criticisms and theory for support. Above all, although the series should not be reduced to “this versus that,” there is sufficient evidence to argue that a conflict of materialistic versus altruistic values is at work in the Harry Potter series. Therefore, the examination of race, hierarchy, and power assists in the recognition of the social and political systems at work in the series. Keywords: J.K. Rowling, Hierarchy, Materialism INTRODUCTION When a skinny boy with black hair, green eyes, and a telltale scar appeared on the scene in 1997, nobody could have predicted the significant impact this seemingly insignificant boy would have on the world. -

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone the First in the Wonderful Best

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone The first in the wonderful best-selling series of novels by writer J.K. Rowling comes ‘Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone’. The journey is just beginning for Harry Potter (Daniel Radcliffe); as an eleven year old orphan who lives in the cupboard under the stairs of his aunt’s house, Harry has not had the best of lives up until this point. He is under-appreciated and frankly unwanted. Harry’s life is about to change; soon he’ll find that his parents we’re not killed in a car crash as he thought, but that they were murdered by a horrifying dark wizard. He will soon attend a wizarding school and learn much that he never thought possible; he will learn how to fly as well as play the sport of Quidditch. Harry’s life will never be the same again! Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Harry Potter is a well-known name when it comes to the world of Wizardry, and he’s got a big reputation to live up to. His reputation, as well as his magical abilities, are about to be put to the test! A mysterious visitor named Dobby the House Elf appears at Harry’s house over the summer and warns Harry not to return to Hogwarts. Knowing his life will be in danger, Harry is determined that this warning holds no merit and returns to Hogwarts, but soon finds that perhaps he shouldn’t have. “The Chamber of Secrets Has Been Opened. -

Lupin's First Lesson

Volume 38 Number 2 Article 10 5-15-2020 Lupin’s First Lesson: An Example of Excellent Teaching Joshua Cole University of Findlay Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Cole, Joshua (2020) "Lupin’s First Lesson: An Example of Excellent Teaching," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 38 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol38/iss2/10 This Notes and Letters is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract A story is often better than abstract theorizing; and the best stories provide opportunities for readers to reflect on their own lives. J.K. Rowling's portrayal of Professor Lupin's first class with Harry's group of Gryffindor third years in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban embodies some useful pedagogical orientations and practices. -

Harry Potter Chamber of Secrets

HARRY POTTER AND THE CHAMBER OF SECRETS screenplay by STEVEN KLOVES based on the novel by J.K. ROWLING FADE IN: 1 EXT. PRIVET DRIVE - DAY 1 WIDE HELICOPTER SHOT. Privet Drive. CAMERA CRANES DOWN, DOWN, OVER the rooftops, FINDS the SECOND FLOOR WINDOW of NUMBER 4. HARRY POTTER sits in the window. 2 OMITTED 2 3 INT. HARRY'S BEDROOM - DAY 3 Harry pages through a SCRAPBOOK, stops on a MOVING PHOTO of Ron and Hermione. SQUAWK! Harry jumps. HEDWIG pecks at the LOCK slung through her cage door, then glowers at Harry. HARRY I can't, Hedwig. I'm not allowed to use magic outside of school. Besides, if Uncle Vernon -- At the sound of the name, HEDWIG SQUAWKS again, LOUDER. UNCLE VERNON (O.S.) Har-ry Pot-ter! HARRY Now you've done it. 4 INT. KITCHEN - DAY 4 While AUNT PETUNIA puts the finishing touches to a PUDDING of WHIPPED CREAM and SUGARED VIOLETS, UNCLE VERNON struggles with DUDLEY'S BOW TIE, all the while glowering at Harry. UNCLE VERNON I warned you. If you can't control that bloody bird, it'll have to go. HARRY She's bored. If I could just let her out for an hour or two -- UNCLE VERNON And have you sending secret messages to your freaky little friends? No, sir. (CONTINUED) THE CHAMBER OF SECRETS - Rev. 1/28/02 2. 4 CONTINUED: 4 HARRY But I haven't gotten any messages. From any of my friends. Not one. All summer. DUDLEY Who'd want to be friends with you? UNCLE VERNON I should think you'd be more grateful.